History of Dice (Dyce) Head Light, Castine, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Once serving a heavy shipping traffic, it [Dice Head Light] is now just one more monument to the romantic and historic town of Castine. -- Robert Thayer Sterling, Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, 1935.

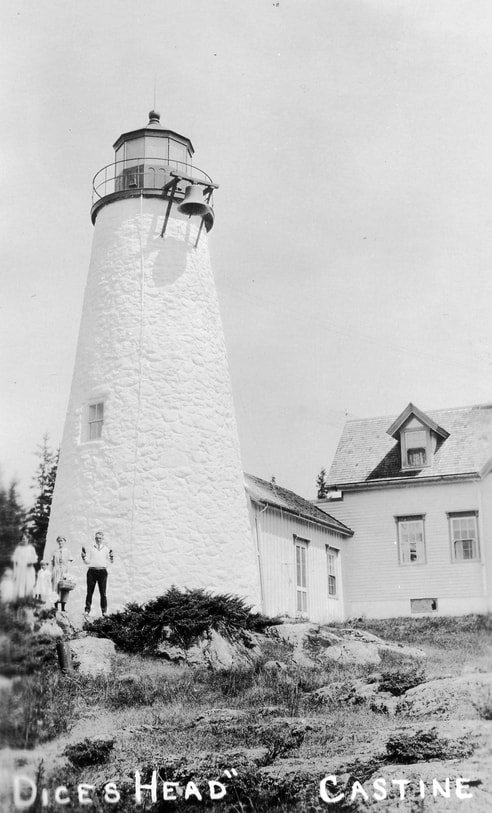

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Castine, occupying a peninsula on the east side of the entrance to the Penobscot River, has a colorful history for a quiet town of only about 600 year-round residents. A French trading post was established, which the French originally called Pentagoet, in 1613. English settlers came to the area after Capt. John Smith charted it in 1614. For two brief periods in the 1670s, the Dutch controlled the area.

Under the terms of a 1687 treaty, the territory went to the French. Castine is named for a French officer, Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, who obtained a large land grant from the king of France. The British occupied the area during the American Revolution. In 1779, Castine was the scene of one of the worst naval defeats in U.S. history, when American ships were forced to retreat into the Penobscot River while under attack from British vessels.

Under the terms of a 1687 treaty, the territory went to the French. Castine is named for a French officer, Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, who obtained a large land grant from the king of France. The British occupied the area during the American Revolution. In 1779, Castine was the scene of one of the worst naval defeats in U.S. history, when American ships were forced to retreat into the Penobscot River while under attack from British vessels.

After another brief British occupation during the War of 1812, Castine came under American control for good. In the mid-nineteenth century, clipper ships left Castine to trade around the world. A number of beautiful sea captains’ homes remain from that period.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

As shipbuilding and lumber traffic on the Penobscot River flourished, Congress appropriated $5,000 for a light station in May 1828. The site chosen was Dice Head, the southernmost point of the Castine peninsula, almost two miles east of the northern end of Islesboro.

The spot is on land once owned by a family named Dyce. Although both spellings have often been used, the “Dice” spelling has predominated.

A conical rubblestone tower—42 feet tall from its base to the focal plane—and an adjacent one-and-one-half-story rubblestone dwelling were soon built, and a newspaper notice on November 5, 1828, announced that the light would go into service that evening.

An octagonal wrought-iron lantern held 10 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, showing a fixed white light 129 feet above mean high water

The spot is on land once owned by a family named Dyce. Although both spellings have often been used, the “Dice” spelling has predominated.

A conical rubblestone tower—42 feet tall from its base to the focal plane—and an adjacent one-and-one-half-story rubblestone dwelling were soon built, and a newspaper notice on November 5, 1828, announced that the light would go into service that evening.

An octagonal wrought-iron lantern held 10 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, showing a fixed white light 129 feet above mean high water

|

The first keeper was Jacob Shelburne, a former sea captain. The Castine Historical Society has preserved a poem he wrote:

I always rise before the sun And up the winding stairs I run Put out the light, when that is done Another day is just begun. So pass my time from day to day While months and years do roll away And when the evening doth return Behold the lamps begin to burn Both bright & clear To show the vessels how to steer And if they steer well to the right They’ll clear the shoal above the light. The light should be on the other side Where the channel is both deep and wide But some Castine men or ginus [genius] bright Said we will petition for a light. They owned the Head, the rocks and land Is a fact we understand That was the reason why they said It shall be built on Dice’s Head |

Shelburne also penned his autobiography while he was keeper at Dice Head, at the age of 75. “In the month of June 1828,” he wrote, “I went to New York. . . . I returned and made interest to get the appointment as keeper of a lighthouse then building on Dice’s Head, near Castine, which appointment I obtained, and am now in possession as keeper of said light.”

Henry D. Hunter of the U.S. revenue cutter Jackson wrote in October 1835 that the lighthouse was poorly situated. “This light should be located on the northern head of Holbrook Island at the eastern entrance to Castine Harbor,” he wrote. “Would then answer as a guide up the Penobscot Bay and a harbor light.”

An 1838 inspection described the station as “in good order,” but I. W. P. Lewis’s 1843 report to Congress told a different story. Lewis wrote that the tower was “laid up in lime mortar of bad quality.” The walls were cracked from frost, the woodwork was rotten, and the tower’s base rested on an uneven ledge “without regard to level.” The dwelling was also leaky and “out of repair altogether.”

Lewis believed that the light was useful for navigation to the harbor of Castine, but he echoed Shelburne and Hunter in his belief that it was out of place to be of much help for the general navigation of Penobscot Bay and the Penobscot River entrance. The light was “intercepted by projecting land,” wrote Lewis, “and can only be seen in a certain direction and limited distance.”

The Lighthouse Board considered discontinuing the light around 1857, but instead major repairs were carried out in 1858. The entire tower was surrounded with a six-sided wooden sheath, and a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the lamps and reflectors. The wooden sheath was removed in the late 1800s. A 1,000-pound fog bell was installed in 1890, to be rung by hand in response to signals from passing vessels. A new hand striker for the bell was installed in 1897.

Edward T. Spurling, formerly at Avery Rock and Franklin Island, became keeper in 1911. After years of island life, the Spurling family’s move to the pleasant village of Castine was a welcome one. In a 1974 interview, one of the keeper’s six children, Beatrice Spurling, recalled life at Dice Head:

For us children it brought us an amazing new life. We could go to an organized school for the first time, and play with other children. Summer life on Dice’s Head was a new world for us. There were ladies with parasols, men in white flannels, buckboards to take them on quiet rides through the Witherle Woods and lots of chances for us to make pin money. I had a summer job at the “Dome of the Rocks” at 50 cents a day. And I could make extra money by going to the houses and helping out. I’ll never forget scrubbing bathtubs for 10 cents a ring.

When the Spurlings first moved to Dice Head, 11-year-old Beatrice attended the grammar school in Castine, which was within walking distance of the light station. It was the first time she had seen a schoolhouse after years of home-schooling at offshore stations.

An 1838 inspection described the station as “in good order,” but I. W. P. Lewis’s 1843 report to Congress told a different story. Lewis wrote that the tower was “laid up in lime mortar of bad quality.” The walls were cracked from frost, the woodwork was rotten, and the tower’s base rested on an uneven ledge “without regard to level.” The dwelling was also leaky and “out of repair altogether.”

Lewis believed that the light was useful for navigation to the harbor of Castine, but he echoed Shelburne and Hunter in his belief that it was out of place to be of much help for the general navigation of Penobscot Bay and the Penobscot River entrance. The light was “intercepted by projecting land,” wrote Lewis, “and can only be seen in a certain direction and limited distance.”

The Lighthouse Board considered discontinuing the light around 1857, but instead major repairs were carried out in 1858. The entire tower was surrounded with a six-sided wooden sheath, and a fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the lamps and reflectors. The wooden sheath was removed in the late 1800s. A 1,000-pound fog bell was installed in 1890, to be rung by hand in response to signals from passing vessels. A new hand striker for the bell was installed in 1897.

Edward T. Spurling, formerly at Avery Rock and Franklin Island, became keeper in 1911. After years of island life, the Spurling family’s move to the pleasant village of Castine was a welcome one. In a 1974 interview, one of the keeper’s six children, Beatrice Spurling, recalled life at Dice Head:

For us children it brought us an amazing new life. We could go to an organized school for the first time, and play with other children. Summer life on Dice’s Head was a new world for us. There were ladies with parasols, men in white flannels, buckboards to take them on quiet rides through the Witherle Woods and lots of chances for us to make pin money. I had a summer job at the “Dome of the Rocks” at 50 cents a day. And I could make extra money by going to the houses and helping out. I’ll never forget scrubbing bathtubs for 10 cents a ring.

When the Spurlings first moved to Dice Head, 11-year-old Beatrice attended the grammar school in Castine, which was within walking distance of the light station. It was the first time she had seen a schoolhouse after years of home-schooling at offshore stations.

The light was electrified in 1935. Two years later the navigational light was moved to a skeleton tower closer to the shore. The keeper’s house and surrounding land became the property of the Town of Castine a short time later. Then, in 1956, the lighthouse tower was turned over to the town.

Artist Nancy Carr, longtime resident of the keeper's house.

The tower lost some chunks of mortar over the years. Inspectors found interior disintegration in the lighthouse that could have eventually caused serious problems. A method of repair called “slurry injection” had to be employed. This process involved slurry—clay or cement mixed with a liquid—being injected through holes in the tower.

In 1997, the voters of Castine approved spending $98,000 to repair the lighthouse. Another $25,000 was approved in March 1998. The town also received $52,000 from the Maine Historic Preservation Committee, and Marty Nally, a contractor from the Campbell Construction Group, carried out the renovation.

The keeper’s house is rented by the town to help pay for the upkeep of the property.

In 1997, the voters of Castine approved spending $98,000 to repair the lighthouse. Another $25,000 was approved in March 1998. The town also received $52,000 from the Maine Historic Preservation Committee, and Marty Nally, a contractor from the Campbell Construction Group, carried out the renovation.

The keeper’s house is rented by the town to help pay for the upkeep of the property.

In April 1999, a late-night fire burned through the roof of the keeper’s house, having apparently started in a faulty chimney. Thankfully, nobody was home, and the tower wasn’t damaged.

After the 1999 fire.

After some debate, the town decided to repair the badly burned dwelling rather than completely rebuilding it. The repairs were completed by September 2000 by Philbrook and Spinney of Bangor. You can read about the restoration of the keeper's house here.

In September 2007, a wind storm or "microburst" toppled the skeletal tower. In late October, it was announced that the Coast Guard would install a new optic in the lighthouse tower, making it an active aid to navigation again. A 250 mm optic went into service on January 1, 2008, exhibiting a white flash every 6 seconds.

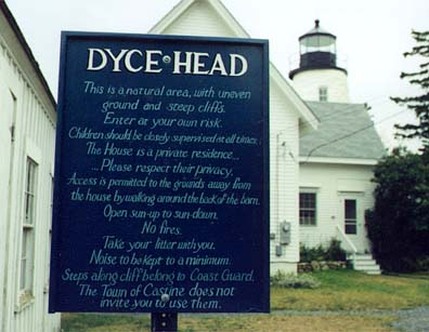

Dice Head Light is a short distance from the Maine Maritime Academy and is easily reached by driving to Castine on Route 166 and turning right on Battle Avenue. The grounds are open to the public daily until sunset. A path leads around the tower, affording good views.

In September 2007, a wind storm or "microburst" toppled the skeletal tower. In late October, it was announced that the Coast Guard would install a new optic in the lighthouse tower, making it an active aid to navigation again. A 250 mm optic went into service on January 1, 2008, exhibiting a white flash every 6 seconds.

Dice Head Light is a short distance from the Maine Maritime Academy and is easily reached by driving to Castine on Route 166 and turning right on Battle Avenue. The grounds are open to the public daily until sunset. A path leads around the tower, affording good views.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Jacob Shelburne (1829-1837); Robert MacFarland (1837-1841); Benjamin Harriman (1841-1845 and 1849-1853); William Hutchings (1845-1849 and 1853-1858); Meltiah Jordan (1858-1861); Samuel Dorr (1861-1864); P. P. Cunningham (1864-1865); George H. Webb (1865-1887); Charles Gott (1887-1911); Adelbert Gott (1911); Edward T. Spurling (1911-1930); Vurney L. King (1930-1937)

Jacob Shelburne (1829-1837); Robert MacFarland (1837-1841); Benjamin Harriman (1841-1845 and 1849-1853); William Hutchings (1845-1849 and 1853-1858); Meltiah Jordan (1858-1861); Samuel Dorr (1861-1864); P. P. Cunningham (1864-1865); George H. Webb (1865-1887); Charles Gott (1887-1911); Adelbert Gott (1911); Edward T. Spurling (1911-1930); Vurney L. King (1930-1937)