History of Pond Island Light, near Georgetown, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Ten-acre Pond Island, just south of the mouth of the Kennebec River, has no pond; the origin of its name is unknown.

Soldiers were quartered on the island during the War of 1812 to prevent the British from entering the Kennebec. In the 1820s, Pond Island became a transfer point for steamer passengers traveling from Augusta to Bangor. At least as early as 1819, “sundry inhabitants” of the area petitioned the government for a lighthouse on Pond Island.

In March 1821, a quarter of a century after a lighthouse was erected in a commanding position on Seguin Island, near the mouth of the Kennebec, Congress appropriated $10.,500 for three light stations, including one on Pond Island. The first small tower was accompanied by a stone dwelling for the keeper, with three rooms on the first floor and two small chambers in the attic.

The station went into service on November 1, 1821.

In March 1821, a quarter of a century after a lighthouse was erected in a commanding position on Seguin Island, near the mouth of the Kennebec, Congress appropriated $10.,500 for three light stations, including one on Pond Island. The first small tower was accompanied by a stone dwelling for the keeper, with three rooms on the first floor and two small chambers in the attic.

The station went into service on November 1, 1821.

In 1823, the keeper, S. L. Rogers, petitioned for a well or cistern at the station. “I suffer great inconvenience,” he wrote, “on account of having no means to obtain fresh water but by transporting it from the mainland.”

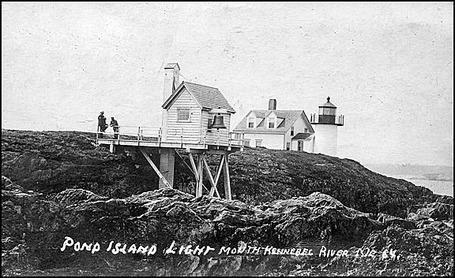

Circa 1885 (U.S. Coast Guard)

Stephen Pleasonton, the Treasury official in charge of lighthouses, subsequently directed that a cistern be built.

The first lighthouse was poorly built and lasted only until 1835. In March of that year, the district lighthouse superintendent advertised for proposals for the building of a new stone tower, 13 feet tall to the base of the lantern, 14 feet in diameter at the base and 10 feet at the top. The tower was topped by an octagonal iron lantern, a little over 7 feet tall. The fixed white light was 55 feet above mean high water.

The station was examined by the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis for his 1843 report to Congress. Lewis found the buildings in poor condition; the 1835 tower, although only a few years old, was leaky. The tower and dwelling had both been built of slate from the island itself, a material that Lewis believed was unfit for the construction of such buildings.

The first lighthouse was poorly built and lasted only until 1835. In March of that year, the district lighthouse superintendent advertised for proposals for the building of a new stone tower, 13 feet tall to the base of the lantern, 14 feet in diameter at the base and 10 feet at the top. The tower was topped by an octagonal iron lantern, a little over 7 feet tall. The fixed white light was 55 feet above mean high water.

The station was examined by the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis for his 1843 report to Congress. Lewis found the buildings in poor condition; the 1835 tower, although only a few years old, was leaky. The tower and dwelling had both been built of slate from the island itself, a material that Lewis believed was unfit for the construction of such buildings.

David Spinney, who had been keeper for several years, added a statement to Lewis’s report. “The house wants pointing,” he wrote, “as it is very leaky and cold, and the chimneys are very bad and dangerous; they want a thorough repair."

Circa early 19002

"The cellar floor has rotted and fallen down. My cisterns are giving out, which will leave us destitute of water.”

Spinney added that the door had come off the lighthouse in a spring storm, the “back-house” was destroyed in a winter gale, and the boat was old and leaky.

Spinney was still keeper when, in November 1849, the vessel Hanover, returning to Bath from Cádiz, Spain, anchored near Pond Island in a storm. As the storm raged, the captain tried to tack around Pond Island and enter the western passage into the river. The ship ran into a bar off nearby Wood Island and soon sank with all 24 crewmen on board.

Only a dog survived. Milton Spinney, son of the keeper, wrote an eyewitness account of the disaster. You can read his letter below.

Spinney added that the door had come off the lighthouse in a spring storm, the “back-house” was destroyed in a winter gale, and the boat was old and leaky.

Spinney was still keeper when, in November 1849, the vessel Hanover, returning to Bath from Cádiz, Spain, anchored near Pond Island in a storm. As the storm raged, the captain tried to tack around Pond Island and enter the western passage into the river. The ship ran into a bar off nearby Wood Island and soon sank with all 24 crewmen on board.

Only a dog survived. Milton Spinney, son of the keeper, wrote an eyewitness account of the disaster. You can read his letter below.

Susan Spinney, wife of Keeper Thomas Spinney, wrote a letter on May 6, 1861. The letter is transcribed below courtesy of Henry Robert Fenech.

A fog bell was added to the station in 1848. After an 1850 inspection, when Ebenezer Jewell was keeper, the local superintendent wrote, “I would like to take the liberty to recommend a new tower and new lantern, as the tower is cracked and the tower very rusty—so much that the glass is continually breaking in the lantern.”

Keeper Napoleon Fickett

Congress appropriated $4,000 in 1851, but the station wasn’t rebuilt until four years later. The present 20-foot brick tower was built and fitted with a fifth-order Fresnel lens in 1855, and a new wood-frame keeper’s dwelling was constructed and connected to the lighthouse tower by a short covered walkway. The focal plane of the fixed light was 52 feet above mean high water.

A ferocious storm that caused widespread damage on September 8, 1869, did not spare Pond Island. The fog bell tower was destroyed, along with the striking mechanism, but the bell was soon re-established. A new, 1,200-pound bell replaced the old one in 1889.

An article by Henry S. Bicknell in the New England Magazine in 1886 providesd a glimpse of life on Pond Island:

We were told that the island provided pasturage sufficient for one cow, but, from a close observation, it was evident that she must be content with two meals a day, or to get an occasional donation from the meadows on the mainland. Twice a year the district inspector makes his rounds, and, during the week previous to his visit, the entire family devote[s] all their energy in scouring and polishing, until everything about the place, from the doorknob to the lenses, fairly sparkles with brilliancy. On these occasions, the light-keeper is seen in his best mood, and is the perfection of politeness and urbanity, for then a hope of reappointment is betrayed in every movement.

Isaac Morrison, an avid fiddle player, became keeper in 1889. A young resident of nearby Popham Beach, Hiram Stevens, rowed out for lessons with the lighthouse keeper. Stevens later became a successful composer and had several pieces performed by John Philip Souza's band.

After four years at nearby Seguin Light, Napoleon Bonaparte Fickett became keeper in 1926. In his 1940 book, Anchor to Windward, Edwin Valentine Mitchell wrote that Fickett’s wife, soon after they arrived on the island, heard the mewing of a cat that seemed to come from underground. It turned out to be the cat of the departing keeper’s family, and it had found a hole leading to cave under the island.

Fickett remained keeper until 1948, when he fell ill and retired. Fickett was followed by a succession of Coast Guard keepers, beginning with Boatswain’s Mate First Class Harvey Lamson.

A ferocious storm that caused widespread damage on September 8, 1869, did not spare Pond Island. The fog bell tower was destroyed, along with the striking mechanism, but the bell was soon re-established. A new, 1,200-pound bell replaced the old one in 1889.

An article by Henry S. Bicknell in the New England Magazine in 1886 providesd a glimpse of life on Pond Island:

We were told that the island provided pasturage sufficient for one cow, but, from a close observation, it was evident that she must be content with two meals a day, or to get an occasional donation from the meadows on the mainland. Twice a year the district inspector makes his rounds, and, during the week previous to his visit, the entire family devote[s] all their energy in scouring and polishing, until everything about the place, from the doorknob to the lenses, fairly sparkles with brilliancy. On these occasions, the light-keeper is seen in his best mood, and is the perfection of politeness and urbanity, for then a hope of reappointment is betrayed in every movement.

Isaac Morrison, an avid fiddle player, became keeper in 1889. A young resident of nearby Popham Beach, Hiram Stevens, rowed out for lessons with the lighthouse keeper. Stevens later became a successful composer and had several pieces performed by John Philip Souza's band.

After four years at nearby Seguin Light, Napoleon Bonaparte Fickett became keeper in 1926. In his 1940 book, Anchor to Windward, Edwin Valentine Mitchell wrote that Fickett’s wife, soon after they arrived on the island, heard the mewing of a cat that seemed to come from underground. It turned out to be the cat of the departing keeper’s family, and it had found a hole leading to cave under the island.

Fickett remained keeper until 1948, when he fell ill and retired. Fickett was followed by a succession of Coast Guard keepers, beginning with Boatswain’s Mate First Class Harvey Lamson.

|

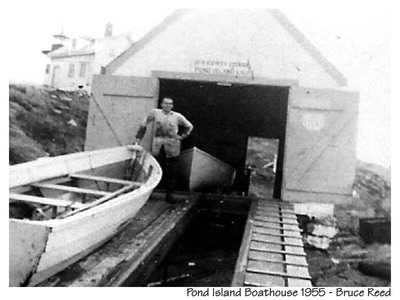

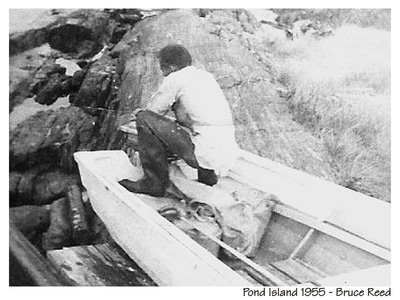

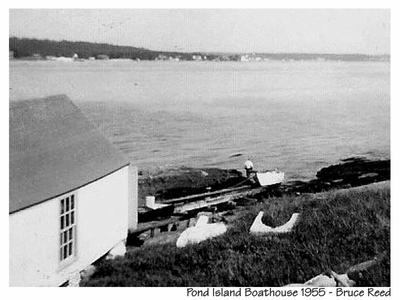

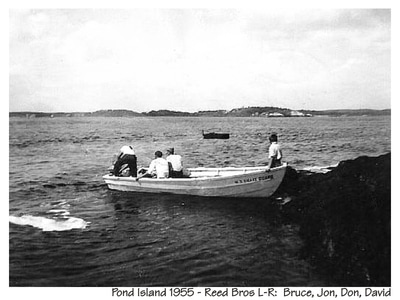

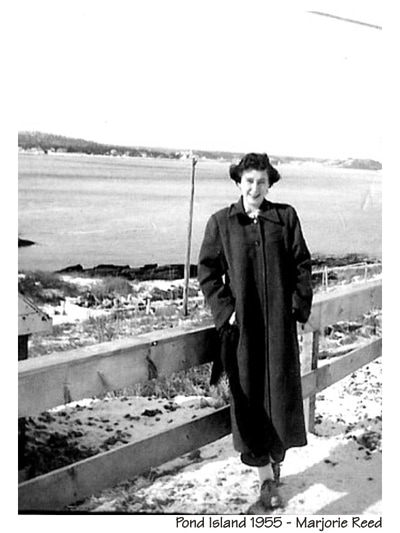

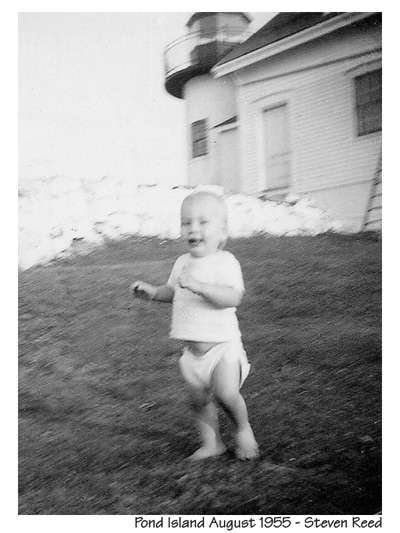

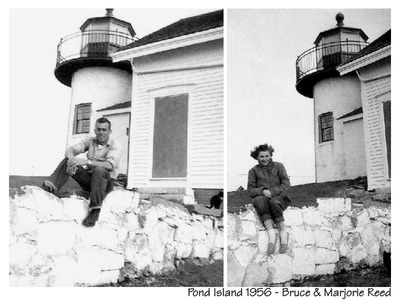

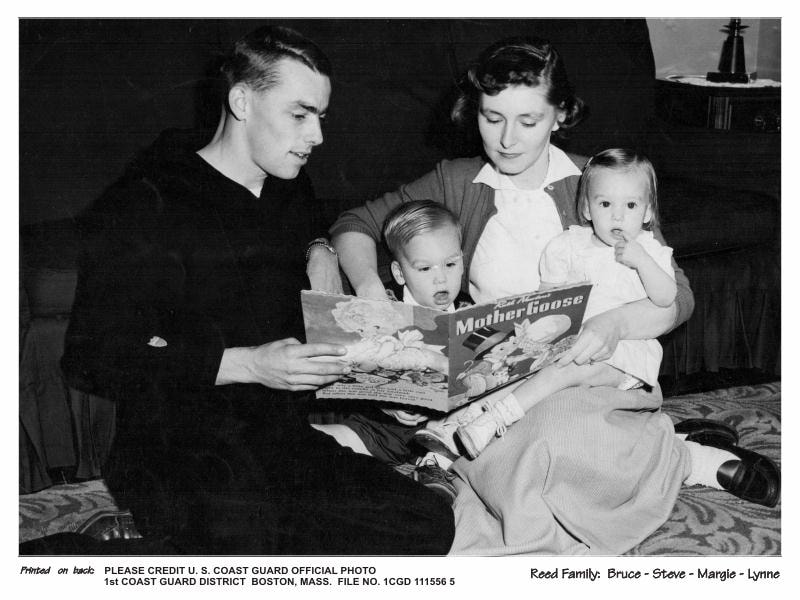

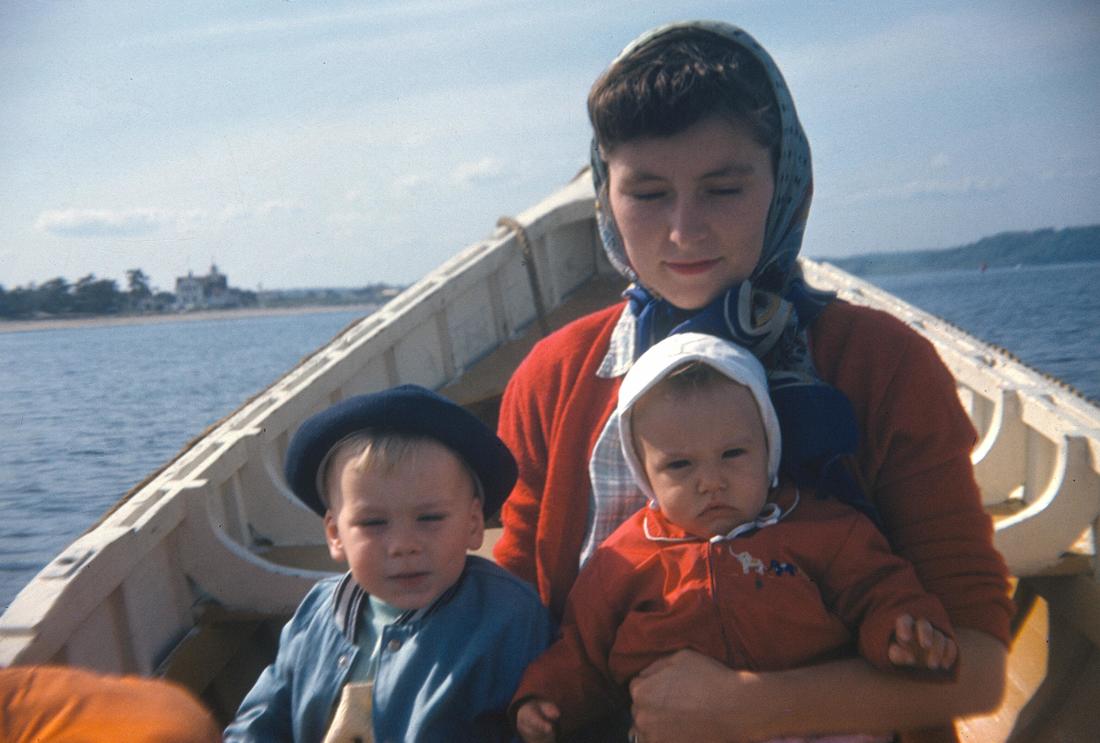

Bruce C. Reed was the Coast Guard keeper 1954-56. He later wrote the following:

Pond Island was a mile out from shore and to get there I had to row a small 16-foot boat. It took about 30 minutes to make the trip. On those occasions when the sea was dangerously rough, the Coast Guard would send a larger boat out to get us off the island. After a while, I received an outboard motor which, when it worked, made the trip easier on me, but it still took a long time. On the island, there was a light tower, a bell tower and a two story residence, all connected by covered passageways. Pond Island was one of the few primitive lighthouses in that area. We had no electricity or plumbing. We had kerosene lamps for light, a coal stove for cooking and heating water, and a coal furnace for heat. Once a year, a large Coast Guard ship would bring us hundreds of sacks of coal to get us through the winter. Our water was collected from the roof when it rained and stored in large concrete tanks in the cellar. There was an old hand pump at the kitchen sink for cold water only. The only way to get hot water was to heat it on the stove. The only bathroom was an outhouse about 20 feet from the back door. |

Our first summer there (just before our son was born) we had a big hurricane. Knowing that winter was coming and we'd have to brave the elements (near zero temperatures and snow drifts) to get to the outhouse, I took action. I pushed that rickety outhouse into the sea. We were thrilled when the Coast Guard supplied us with a brand new chemical toilet inside the building. We also had a gasoline powered washing machine and a kerosene refrigerator, which sometimes froze everything in it.

The light keepers' duties consisted mainly of lighting the light at sundown, extinguishing the light at sunrise and keeping the bell going in foggy weather. The light, inside a large prism lens could be seen for 16 miles and the bell could be heard for 2 miles. My other duties were keeping the station clean and in good repair, like constantly painting the main building and the outbuildings.

Both of our children were born while we were stationed at Pond Island. Despite the additional problems in raising infants under these conditions, including the trips ashore in the rowboat, we loved our isolated life.

The photos below of the Reed family are courtesy of Bruce Reed's son, Steve Reed.

The light keepers' duties consisted mainly of lighting the light at sundown, extinguishing the light at sunrise and keeping the bell going in foggy weather. The light, inside a large prism lens could be seen for 16 miles and the bell could be heard for 2 miles. My other duties were keeping the station clean and in good repair, like constantly painting the main building and the outbuildings.

Both of our children were born while we were stationed at Pond Island. Despite the additional problems in raising infants under these conditions, including the trips ashore in the rowboat, we loved our isolated life.

The photos below of the Reed family are courtesy of Bruce Reed's son, Steve Reed.

In August 1960, the Coast Guard announced that they were automating the station.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

The fog signal was put under the remote control of the Coast Guard station at Popham Beach. The last keeper was Ronald D. Howard.

All the buildings except the lighthouse tower were destroyed by the Coast Guard. Today the island is managed as a bird refuge by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Pond Island Light, still an active aid to navigation, can be viewed distantly from the Popham Beach area.

Closer views are available from tour boats out of Boothbay Harbor and Bath's Maine Maritime Museum.

All the buildings except the lighthouse tower were destroyed by the Coast Guard. Today the island is managed as a bird refuge by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Pond Island Light, still an active aid to navigation, can be viewed distantly from the Popham Beach area.

Closer views are available from tour boats out of Boothbay Harbor and Bath's Maine Maritime Museum.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Samuel L. Rodgers (1823-1831); Joseph Rogers (c. 1820s); James Lennan (1833-1836); David Spinney (1837?-1849); Octavius Stevens (1849); Ebenezer Sewell (Jewell ?) (1849-1852); Thomas Spinney (c. 1852-1861); Samuel Gill (1861-1864); Hannah Gill (164-1867); William G. Todd (1867-1871); Washington Oliver (1871-1878); Charles S. Brown (1878-1889); Edwin Wyman (1889) Isaac Morrison (1889-1903); Ezra Morrison (1903-1921); Napoleon B. Fickett (1926-1948); Harvey Lamson (Coast Guard, c. 1948-1951); Bruce C. Reed (Coast Guard, 1954-1956); Ronald D. Howard (Coast Guard, Feb. 1960-Sept. 1960)

Samuel L. Rodgers (1823-1831); Joseph Rogers (c. 1820s); James Lennan (1833-1836); David Spinney (1837?-1849); Octavius Stevens (1849); Ebenezer Sewell (Jewell ?) (1849-1852); Thomas Spinney (c. 1852-1861); Samuel Gill (1861-1864); Hannah Gill (164-1867); William G. Todd (1867-1871); Washington Oliver (1871-1878); Charles S. Brown (1878-1889); Edwin Wyman (1889) Isaac Morrison (1889-1903); Ezra Morrison (1903-1921); Napoleon B. Fickett (1926-1948); Harvey Lamson (Coast Guard, c. 1948-1951); Bruce C. Reed (Coast Guard, 1954-1956); Ronald D. Howard (Coast Guard, Feb. 1960-Sept. 1960)