History of Chatham Light, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Nowhere on the Cape's shorelines has the sea kept busier at her handiwork than among these storm-bitten sands. Directly to the south of the bluff, Monomoy lies beckoning like the bony finger of death which it has been to countless ships. - Josef Berger, Cape Cod Pilot, 1937.

The 1841 towers (National Archives)

Chatham, nestled at Cape Cod's southeast corner, was named for an English seaport and incorporated in 1712. Maritime traffic passing the Cape was heavy by the nineteenth century. The waters off Chatham were a menace, with strong currents and dangerous shoals. Mariners talked of a ghostly rider on a white horse who appeared on stormy nights, swinging a lantern that lured mariners to their doom.

In April 1806, nine years after the establishment of the Cape's first lighthouse at North Truro, Congress appropriated $5,000 for a second station at Chatham. A second appropriation of $2,000 was made in 1808. In order to distinguish Chatham from Highland Light, it was decided that the new station would have two fixed white lights. Two octagonal wooden towers, each 40 feet tall and about 70 feet apart from each other, were erected on moveable wooden skids about 70 feet apart. A small dwelling house was also built, with only one bedroom. Samuel Nye was approved as the first keeper by President Thomas Jefferson.

Lt. Edward D. Carpender of the U.S. Navy visited the station in 1838. Carpender's report described the 1808 towers as "very much shaken and decayed, so as to make it dangerous to ascend them in windy weather." The lighting apparatus at the time consisted of six lamps with and 8 1/2-inch reflectors, with green glass lenses in front of them.

An appropriation for the rebuilding of the station was requested for the next two years. In late 1841, the Treasury Department announced, "The two light-houses at Chatham . . . being entirely unfit for use, were taken down and rebuilt at an expense of $6,750, out of the general annual appropriation for the present year. They were fitted upon the improved plan, with fourteen-inch reflectors."

The two new brick towers, completed in the summer of 1841, were each 30 feet tall. A new brick dwelling was connected to both of the towers by covered walkways. The contractor responsible for the rebuilding of the station was Winslow Lewis.

In April 1806, nine years after the establishment of the Cape's first lighthouse at North Truro, Congress appropriated $5,000 for a second station at Chatham. A second appropriation of $2,000 was made in 1808. In order to distinguish Chatham from Highland Light, it was decided that the new station would have two fixed white lights. Two octagonal wooden towers, each 40 feet tall and about 70 feet apart from each other, were erected on moveable wooden skids about 70 feet apart. A small dwelling house was also built, with only one bedroom. Samuel Nye was approved as the first keeper by President Thomas Jefferson.

Lt. Edward D. Carpender of the U.S. Navy visited the station in 1838. Carpender's report described the 1808 towers as "very much shaken and decayed, so as to make it dangerous to ascend them in windy weather." The lighting apparatus at the time consisted of six lamps with and 8 1/2-inch reflectors, with green glass lenses in front of them.

An appropriation for the rebuilding of the station was requested for the next two years. In late 1841, the Treasury Department announced, "The two light-houses at Chatham . . . being entirely unfit for use, were taken down and rebuilt at an expense of $6,750, out of the general annual appropriation for the present year. They were fitted upon the improved plan, with fourteen-inch reflectors."

The two new brick towers, completed in the summer of 1841, were each 30 feet tall. A new brick dwelling was connected to both of the towers by covered walkways. The contractor responsible for the rebuilding of the station was Winslow Lewis.

Collins Howe, a Cape Cod fisherman who had lost a leg in an accident, became keeper of the Chatham Lights shortly before the new towers were built, at a yearly salary of $400.

The 1841 towers with the lanterns installed in 1857. Courtesy of Anna Woodland.

The house had such a poor foundation that rats had burrowed in and infested the cellar. A storm in October 1841 broke 17 panes of glass in the lanterns, which Keeper Howe blamed on poor construction.

Howe lost his job as keeper in 1845 for political reasons. The next keeper was Simeon Nickerson. Nickerson died while keeper and his wife, Angeline, took over his duties. Maybe the rats had subsided, because Collins Howes decided he wanted his position back and tried to have Angeline Nickerson removed from the station.

Joshua Nickerson of Chatham wrote a letter to President Taylor about the condition of the station:

I can testify that it has never been in a better condition than since it has been under her charge, nor is there any Light upon the Coast superior to it.

Howe lost his job as keeper in 1845 for political reasons. The next keeper was Simeon Nickerson. Nickerson died while keeper and his wife, Angeline, took over his duties. Maybe the rats had subsided, because Collins Howes decided he wanted his position back and tried to have Angeline Nickerson removed from the station.

Joshua Nickerson of Chatham wrote a letter to President Taylor about the condition of the station:

I can testify that it has never been in a better condition than since it has been under her charge, nor is there any Light upon the Coast superior to it.

President Taylor ruled in favor of Angeline Nickerson, who remained keeper for about a decade.

In 1857, the Chatham Lights received fourth-order Fresnel lenses, each showing a fixed white light. The lamps were fueled by lard oil.

Captain Josiah Hardy (left) served as keeper at Chatham from 1872 to 1899. In his 1946 book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow wrote about a visit with the Harding family of Chatham:

Mrs. Harding went on with her thoughts. "There's an interesting bit about Chatham Light I have," she reminisced. "One day in the 1880s my husband, Heman, and Captain Josiah Hardy's son, Samuel, were playing near the light, when the veteran white-whiskered light keeper strode over to them. He had just finished calculations for the day, and there was a pleased expression in his face. 'I want you two boys to remember this day as long as you live,' said the captain. 'I have seen as many ships today as there are days in the year.' "

Captain Josiah Hardy (left) served as keeper at Chatham from 1872 to 1899. In his 1946 book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, Edward Rowe Snow wrote about a visit with the Harding family of Chatham:

Mrs. Harding went on with her thoughts. "There's an interesting bit about Chatham Light I have," she reminisced. "One day in the 1880s my husband, Heman, and Captain Josiah Hardy's son, Samuel, were playing near the light, when the veteran white-whiskered light keeper strode over to them. He had just finished calculations for the day, and there was a pleased expression in his face. 'I want you two boys to remember this day as long as you live,' said the captain. 'I have seen as many ships today as there are days in the year.' "

...It must have been a wonderful sight, those 365 barks, brigs, schooners, and ships as they sailed to all ports of the world by Chatham Light. Today, when a sail is raised from Chatham Bluff, it is considered an event, and there are almost a score of days every month when no white sail lends its enchantment to the horizon.

Captain Josiah Hardy

In 1875, Keeper Hardy counted 16,000 vessels passing the lighthouse. He reported often on the serious erosion problems, but little was done to shore up the crumbling cliff.

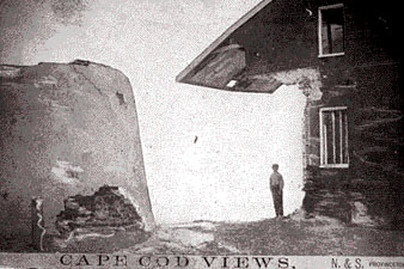

A tremendous storm hit Cape Cod in November 1870. Before the storm, the Chatham lights were 228 feet from the edge of the 50-foot bluff. The storm had broken through the outer beaches, and the erosion accelerated. By 1877 the light towers stood only 48 feet from the brink.

The authorities took note of the rampant erosion and moved quickly to rebuild the station, across the road and much farther from the edge of the bluff.

Two 48-foot, conical cast-iron towers were erected in 1877, along with double one-and-one-half-story wood-frame dwellings for the principal keeper, the assistant keeper, and their families.

On September 30, 1879, the old south tower teetered 27 inches from oblivion. Another two months passed, and a third of the foundation hung over the edge. Around this time some local boys found ancient coins, rumored to be pirate treasure, under the lighthouse.

A tremendous storm hit Cape Cod in November 1870. Before the storm, the Chatham lights were 228 feet from the edge of the 50-foot bluff. The storm had broken through the outer beaches, and the erosion accelerated. By 1877 the light towers stood only 48 feet from the brink.

The authorities took note of the rampant erosion and moved quickly to rebuild the station, across the road and much farther from the edge of the bluff.

Two 48-foot, conical cast-iron towers were erected in 1877, along with double one-and-one-half-story wood-frame dwellings for the principal keeper, the assistant keeper, and their families.

On September 30, 1879, the old south tower teetered 27 inches from oblivion. Another two months passed, and a third of the foundation hung over the edge. Around this time some local boys found ancient coins, rumored to be pirate treasure, under the lighthouse.

Fishermen placed bets on the exact time that tower would fall. Finally, at 1:00 PM on December 15 the south tower fell to the beach below.

Fifteen months later, the old keeper's house and the old north tower succumbed.

The next keeper after Josiah Hardy was Charles H. Hammond. James T. Allison took over as principal keeper in 1907 and stayed for about 20 years.

By the early 1900s, the Lighthouse Board began phasing out twin light stations as an unnecessary expense. The north light was moved up the coast to Eastham to replace the survivor of the "Three Sisters" in 1923, ending 115 years of twin lights at Chatham.

A new rotating lens was placed in the remaining tower, along with an incandescent oil-vapor lamp. In 1939, the Coast Guard electrified the light -- which had been fueled by kerosene since 1882 -- and increased its intensity from 30,000 to 800,000 candlepower (much like replacing appliance parts to increase efficiency).

The next keeper after Josiah Hardy was Charles H. Hammond. James T. Allison took over as principal keeper in 1907 and stayed for about 20 years.

By the early 1900s, the Lighthouse Board began phasing out twin light stations as an unnecessary expense. The north light was moved up the coast to Eastham to replace the survivor of the "Three Sisters" in 1923, ending 115 years of twin lights at Chatham.

A new rotating lens was placed in the remaining tower, along with an incandescent oil-vapor lamp. In 1939, the Coast Guard electrified the light -- which had been fueled by kerosene since 1882 -- and increased its intensity from 30,000 to 800,000 candlepower (much like replacing appliance parts to increase efficiency).

George F. Woodman, a veteran of 24 years of service at a number of Massachusetts lighthouses and lifesaving stations, became keeper in 1928. He was a perennial recipient of the superintendent's efficiency star for excellent service.

Circa 1950s, courtesy of Melanie Pike

Woodman was still there when a 1937 article reported that the station had more than 1,500 visitors between mid-July and mid-September of 1936. Woodman had the added duty of displaying storm signal flags on a nearby 75-foot tower as needed, as well as storm warning lights at night.

George T. Gustavus retired as keeper in October 1945. Gustavus had previously served at Tarpaulin Cove Light, where he and his wife, Mabel, had their second child.

They went from there to Eastern Point Light in Gloucester, then Thacher Island, Cuttyhunk, Bird Island, Dumpling Rock Light, and Prudence Island in Rhode Island. By the time they left Cuttyhunk there were 10 children in the Gustavus family.

George T. Gustavus retired as keeper in October 1945. Gustavus had previously served at Tarpaulin Cove Light, where he and his wife, Mabel, had their second child.

They went from there to Eastern Point Light in Gloucester, then Thacher Island, Cuttyhunk, Bird Island, Dumpling Rock Light, and Prudence Island in Rhode Island. By the time they left Cuttyhunk there were 10 children in the Gustavus family.

Gustavus lost his wife and youngest son in the hurricane of 1938 while at Prudence Island. He went to Nobska Point Light as keeper, and finally Chatham.

Left: Keeper George T. Gustavus. Courtesy of his granddaughter, Joan Kenworthy.

Historian Edward Rowe Snow interviewed Keeper Gustavus just after retirement for his 1946 book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod:

I retired from service October 20, 1945. I guess the world does not owe me much; have to make the best from now on. I was married again in 1943. My wife Edith is my good companion to look after things. The children are all in other parts, I'm grand-daddy quite a number of times.

Historian Edward Rowe Snow interviewed Keeper Gustavus just after retirement for his 1946 book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod:

I retired from service October 20, 1945. I guess the world does not owe me much; have to make the best from now on. I was married again in 1943. My wife Edith is my good companion to look after things. The children are all in other parts, I'm grand-daddy quite a number of times.

In 1969, the Fresnel lens and the entire lantern were removed. Modern aerobeacons producing a rotating 2.8- million-candlepower light were installed, and a new, larger lantern was constructed to accommodate the larger apparatus. Five years later, the old lantern and lens were put on display on the grounds of the Chatham Historical Society's Atwood House Museum on Stage Harbor Road, just a few minutes from the lighthouse (below right).

The light was automated in 1982. It remains an active aid to navigation, and the 1877 keeper's dwelling is used for Coast Guard housing. In August 1993, the top of the lantern was temporarily removed and new DCB-224 aerobeacons were installed.

The erosion near Chatham Light had slowed in this century, but in recent years a new threat has developed. A new break in the barrier beach east of the lighthouse occurred during a winter storm in January 1987, and storms in 1991 exacerbated the situation.

The Town of Chatham has been implementing erosion control measures, but the time will come, sooner or later, when Chatham Light will have to be moved or follow in the wake of its predecessors.

The erosion near Chatham Light had slowed in this century, but in recent years a new threat has developed. A new break in the barrier beach east of the lighthouse occurred during a winter storm in January 1987, and storms in 1991 exacerbated the situation.

The Town of Chatham has been implementing erosion control measures, but the time will come, sooner or later, when Chatham Light will have to be moved or follow in the wake of its predecessors.

Chatham is a charming town with many lovely old houses, but it often gets very congested in the summer.

Inside the tower

Chatham Light is easy to reach by car. A right on Shore Road at the eastern end of Main Street will take you right to it. Bear in mind that the parking lot is frequently full in season.

The monument standing near the foundation of the old north light was erected in memory of seven members of the crew of the Monomoy Life Saving Station, who died attempting to save the crew of a coal barge in 1902.

The monument standing near the foundation of the old north light was erected in memory of seven members of the crew of the Monomoy Life Saving Station, who died attempting to save the crew of a coal barge in 1902.

Over the world wherever I fare

Sea-roving up and down

Forever in my heart I bear

The Lights Of Chatham Town.

- Carol Wight

Sea-roving up and down

Forever in my heart I bear

The Lights Of Chatham Town.

- Carol Wight

Click here for an interview with John Guertsen of the Coast Guard Auxilary about Chatham Light on the "Light Hearted" podcast (July 2019):

Keepers: This list of keepers is a work in progress. Anyone who copies it to another site does so at their own risk; I can't guarantee that the information is correct or complete. If you have information to contribute, please email [email protected].

Samuel Nye (1808-?); Joseph Loveland (?); Samuel Stinson (Stimson?) (c. 1832): Collins Howe (1841-1845); Simeon Nickerson (1845-1848, died in service); Angeline Nickerson (1848-1862); Warren Rodgers (assistant 1859-1868); Charles Smith (1862-1872); F. G. Nickerson (assistant, 1863-1867); Josiah Hardy (assistant 1872, keeper 1872-1899); Cyrenus C. Hamilton (assistant 1872); Charles H. Hammond (1899-190?); Thomas F. McDonald (c. early 1900s); James Allison (1907-1927); George Woodman (1928-?); George Gustavas (1941-1945).

Samuel Nye (1808-?); Joseph Loveland (?); Samuel Stinson (Stimson?) (c. 1832): Collins Howe (1841-1845); Simeon Nickerson (1845-1848, died in service); Angeline Nickerson (1848-1862); Warren Rodgers (assistant 1859-1868); Charles Smith (1862-1872); F. G. Nickerson (assistant, 1863-1867); Josiah Hardy (assistant 1872, keeper 1872-1899); Cyrenus C. Hamilton (assistant 1872); Charles H. Hammond (1899-190?); Thomas F. McDonald (c. early 1900s); James Allison (1907-1927); George Woodman (1928-?); George Gustavas (1941-1945).