History of Edgartown Lighthouse, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

The first white settlement on Martha's Vineyard was established in 1642, and the early settler Thomas Mayhew called the area "Great Harbor." The town's spacious harbor is bounded by Chappaquiddick Island to the south and east.

U.S. Coast Guard

Martha's Vineyard, like Nantucket, developed a booming whaling industry in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Between them, Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard owned one quarter of America's whaling fleet just before the Revolution. By the 1800s, more than 100 Edgartown men were captains of whaling ships. The magnificent houses built for these captains are still among the most beautiful in New England.

The whaling industry was going strong in 1828 when Congress appropriated $5,500 and the federal government purchased a plot of land from Seth Vincent for $80 for the purpose of building a lighthouse at the entrance to Edgartown Harbor.

The whaling industry was going strong in 1828 when Congress appropriated $5,500 and the federal government purchased a plot of land from Seth Vincent for $80 for the purpose of building a lighthouse at the entrance to Edgartown Harbor.

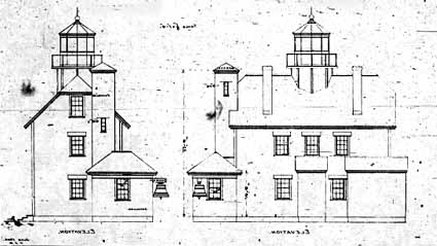

A two-story house with a lantern on the roof was built for about $4,000, with a fixed white light visible for 14 miles.

The building was erected by a Mr. Bowker, working for contractor Winslow Lewis. The house had three rooms on the first floor and two on the second.

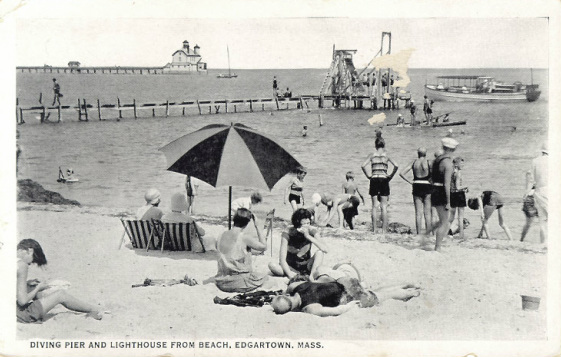

The lighthouse sat offshore on pilings, meaning the keeper originally had to row a short distance to reach the mainland. In 1830, a wooden causeway was built to the lighthouse at a cost of $2,500. The causeway became known locally as the "Bridge of Sighs," because men about to leave on whaling voyages would frequently walk there with their wives or girlfriends.

The lighthouse sat offshore on pilings, meaning the keeper originally had to row a short distance to reach the mainland. In 1830, a wooden causeway was built to the lighthouse at a cost of $2,500. The causeway became known locally as the "Bridge of Sighs," because men about to leave on whaling voyages would frequently walk there with their wives or girlfriends.

The first keeper, Jeremiah Pease, was also an accountant and surveyor. He kept the light for two separate stretches of 13 and 6 years.

From A Trip to Cape Cod, 1898

Pease, a Democrat, was removed from his job twice for political reasons by the Whigs.

In 1838, Lt. Edward D. Carpender examined the station and wrote:

...It cannot be long before Government will have to reconstruct this breakwater and Light-house, as the worms have made great havoc with them, and the sea threatens them with total destruction.

Sylvanus Crocker became keeper in 1841 for $350 per year. Crocker had been employed in the construction of the lighthouse as a carpenter. In October 1842, he reported:

The whole structure was badly done. The light-house originally stood on a wooden pier; three years ago it was necessary to replace this with one of stone, the old pier being entirely decayed and rotten. The frame of the house was light and weak, and the building always leaky. The lantern stands upon the roof of the house, and is shaken by the force of storms, causing other leaks in the roof... The causeway has been knocked to pieces five or six times, and has been an expensive concern to keep in sufficient order to cross it with safety. It is my opinion, the whole establishment was very badly built in the first place.

In 1838, Lt. Edward D. Carpender examined the station and wrote:

...It cannot be long before Government will have to reconstruct this breakwater and Light-house, as the worms have made great havoc with them, and the sea threatens them with total destruction.

Sylvanus Crocker became keeper in 1841 for $350 per year. Crocker had been employed in the construction of the lighthouse as a carpenter. In October 1842, he reported:

The whole structure was badly done. The light-house originally stood on a wooden pier; three years ago it was necessary to replace this with one of stone, the old pier being entirely decayed and rotten. The frame of the house was light and weak, and the building always leaky. The lantern stands upon the roof of the house, and is shaken by the force of storms, causing other leaks in the roof... The causeway has been knocked to pieces five or six times, and has been an expensive concern to keep in sufficient order to cross it with safety. It is my opinion, the whole establishment was very badly built in the first place.

In 1847, a new stone breakwater was built for $4700, replacing the old wooden one. An 1850 inspection reported that Keeper Crocker was not living in the lighhouse, but had moved into another house close by, undoubtedly because he considered the lighthouse unsafe.

U.S. Coast Guard

A fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the old lamps and reflectors in 1856. The dwelling and walkway were repaired many times through the years. A storage building, oil house, and a fog bell and striking machinery were added over the years.

Probably because of the building’s defects and the its vulnerable location, the keepers generally only stayed for only a few years. Henry L. Thomas—after a dozen years as keeper at Cape Poge Light on nearby Chappaquiddick Island—was in charge from 1931 to 1938, and conditions at the lighthouse had improved somewhat by the time a 1934 newspaper article described his family’s life:

Their lighthouse home has practically all the conveniences that go to make the modern home comfortable, except for electricity. As the lighthouse is located a quarter of a mile out from shore it has never been wired for electricity, although they have a radio, running water, and a modern heating plant.

The dwelling and walkway were repaired many times through the years. The hurricane of September 21, 1938, pretty much finished off the old building. The Coast Guard took over the Lighthouse Service in 1939, and they quickly demolished the dilapidated structure.

Probably because of the building’s defects and the its vulnerable location, the keepers generally only stayed for only a few years. Henry L. Thomas—after a dozen years as keeper at Cape Poge Light on nearby Chappaquiddick Island—was in charge from 1931 to 1938, and conditions at the lighthouse had improved somewhat by the time a 1934 newspaper article described his family’s life:

Their lighthouse home has practically all the conveniences that go to make the modern home comfortable, except for electricity. As the lighthouse is located a quarter of a mile out from shore it has never been wired for electricity, although they have a radio, running water, and a modern heating plant.

The dwelling and walkway were repaired many times through the years. The hurricane of September 21, 1938, pretty much finished off the old building. The Coast Guard took over the Lighthouse Service in 1939, and they quickly demolished the dilapidated structure.

Plans to erect a beacon on a skeleton tower were objected to by residents, so the Coast Guard came up with an alternate plan: the relocation of an 1881 cast-iron tower from Crane's Beach in Ipswich.

The lighthouse was disassembled and brought by barge to Edgartown. The 45-foot tower received a modern automatic light flashing red every six seconds.

The lighthouse was leased to the Vineyard Environmental Research Institute (V.E.R.I.) in 1985. A new plastic lens was installed in 1990 and the light was converted to solar power. In 1994 the license was transferred to the Martha's Vineyard Museum.

The lighthouse was leased to the Vineyard Environmental Research Institute (V.E.R.I.) in 1985. A new plastic lens was installed in 1990 and the light was converted to solar power. In 1994 the license was transferred to the Martha's Vineyard Museum.

A memorial was established at the base of the lighthouse in 2001. The Martha's Vineyard Children's Lighthouse Memorial consists of stones engraved with the names of children who have died, along with part of a poem by Tomas Napoleon called A Remembrance of an Unforgotten Vineyard Summer.

''These kids are bright lights that shine on forever,'' said Roberta Hoffman, who bought a stone for her son Aaron, who died in 1994 at age 18 after a five-year battle with cancer.

'What better way to commemorate them than with a lighthouse meant to stay lit eternally.''

Children's Lighthouse Memorial

'What better way to commemorate them than with a lighthouse meant to stay lit eternally.''

Children's Lighthouse Memorial

Over the decades, sand gradually filled in the area between the lighthouse and the mainland, so that today Edgartown Light is on a beach. The Harbor View Hotel overlooks the picturesque site, and wedding parties frequently walk down to the lighthouse for photographs. Edgartown Light also made a brief appearance in the movie Jaws.

In 2007, the Martha's Vineyard Museum received funds from the town of Edgartown through the Community Preservation Act for a restoration of the lighthouse.

The renovations included the installation of new windows with glass panes and a spiral staircase (right) to the top of the tower. Previously, there had been only a ladder.

The lighthouse is open to the public in season. Click here for the schedule.

The renovations included the installation of new windows with glass panes and a spiral staircase (right) to the top of the tower. Previously, there had been only a ladder.

The lighthouse is open to the public in season. Click here for the schedule.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Jeremiah Pease (1828-1841 and 1843-1849); Sylvanus Crocker (1841-1843 and 1849-1853); William Vinson (1853-1855); James Blankenship (1855-1861); William Vincent (1861-1866); Zolmond Steward (1866-c. 1870); Benjamin Huxford (c. 1870-?); Joseph H. Barrus (1919-1931); Henry L. Thomas (1931-1938); Fred Vidler (1938)

Jeremiah Pease (1828-1841 and 1843-1849); Sylvanus Crocker (1841-1843 and 1849-1853); William Vinson (1853-1855); James Blankenship (1855-1861); William Vincent (1861-1866); Zolmond Steward (1866-c. 1870); Benjamin Huxford (c. 1870-?); Joseph H. Barrus (1919-1931); Henry L. Thomas (1931-1938); Fred Vidler (1938)