History of Petit Manan Lighthouse, near Corea, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Petit Manan, a low, rocky island about 14 miles from Bar Harbor, was named by explorer Samuel de Champlain along with nearby Petit Manan Point because they reminded him of Grand Manan to the northeast. "Manan" apparently comes from a Micmac Indian word meaning "island out to sea." According to Louise Dickinson Rich, author of The Coast of Maine, Petit Manan Island is pronounced by locals, "Titm'nan."

President James Monroe authorized the building of a lighthouse on Petit Manan Island in 1817. It served to guide shipping traffic toward several bays and harbors in the vicinity, and also to warn mariners of a dangerous bar between the island and Petit Manan Point on the mainland.

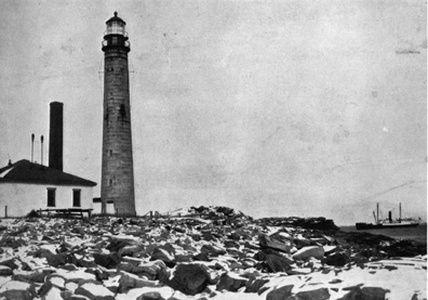

Right: Petit Manan Light c. 1859 (National Archives). Note that the remains of the 1817 lighthouse can be seen at the right.

In 1831, it was reported that the original small stone lighthouse was in very poor condition and was "positively dirty." The keeper, Robert Leighton, had left his wife in charge of the lighthouse. Leighton was dismissed, and he died a year later. His wife applied for the position, but it was awarded instead to Patrick Campbell.

Right: Petit Manan Light c. 1859 (National Archives). Note that the remains of the 1817 lighthouse can be seen at the right.

In 1831, it was reported that the original small stone lighthouse was in very poor condition and was "positively dirty." The keeper, Robert Leighton, had left his wife in charge of the lighthouse. Leighton was dismissed, and he died a year later. His wife applied for the position, but it was awarded instead to Patrick Campbell.

An 1851 inspection made it clear that a new tower was needed. The present 119-foot granite tower, Maine's second tallest (to Boon Island), was built in 1854. The new lighthouse was fitted with a second-order Fresnel lens.

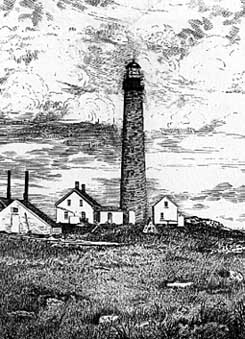

19th century engraving

The tall, slender lighthouse had some close calls in storms. An 1856 gale weakened the structure and knocked out some blocks in the wall.

In 1869, a storm made the tower sway violently causing the clockwork weights that turned the lens to come loose and fall. The force of the falling weights destroyed some of the steps in the tower's cast-iron spiral stairway.

In 1887, the tower was strengthened with the addition of iron tie rods driven from the top to huge bolts in the lower section. This strengthening has enabled Petit Manan Light to weather many more years of storms.

Petit Manan is considered one of the foggiest spots on the Maine coast, with an average of about 70 foggy days each year. A fog bell and striking mechanism installed in 1855 were replaced by a steam-driven fog whistle in 1869.

Birds frequently collided with the lantern at Petit Manan. Mary Bradford Crowninshield's 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses describes an early morning inspector's visit that found hundreds of dead birds scattered near the tower.

In 1869, a storm made the tower sway violently causing the clockwork weights that turned the lens to come loose and fall. The force of the falling weights destroyed some of the steps in the tower's cast-iron spiral stairway.

In 1887, the tower was strengthened with the addition of iron tie rods driven from the top to huge bolts in the lower section. This strengthening has enabled Petit Manan Light to weather many more years of storms.

Petit Manan is considered one of the foggiest spots on the Maine coast, with an average of about 70 foggy days each year. A fog bell and striking mechanism installed in 1855 were replaced by a steam-driven fog whistle in 1869.

Birds frequently collided with the lantern at Petit Manan. Mary Bradford Crowninshield's 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses describes an early morning inspector's visit that found hundreds of dead birds scattered near the tower.

The keeper told the inspector, "They often fly against the lantern. Many a time, in a high wind, I hear 'em flappin' against the glass, an' I wonder if they don't obscure the light when they come in such numbers."

A lighthouse tender can be seen offshore in this U.S. Lighthouse Service photo

During World War I, the Lighthouse Bureau authorized J.C. Strout, owner of nearby Green Island, to pasture sheep on a part of Petit Manan not being used by the keepers.

On Dec. 29. 1916, Keeper Eugene Ingalls left Petit Manan in a powerboat to meet with his wife, Inez Robinson Ingalls, who was visiting with her parents at Moose Peak Light. Her father, Herbert Robinson, was the keeper there. Ingalls’ boat was lost in heavy seas; a search found the capsized boat but Ingalls’ body was never found.

Maizie Freeman Anderson grew up at Petit Manan, where her father James H. Freeman was keeper in the 1930s. She wrote about her childhood there for Down East magazine:

No trees grew in the shallow soil of Petit Manan, but there were patches of grass and a few hardy wildflowers grew in abundance, even among the rocks -- sweet pea, buttercups and others. We had a small cranberry bog yielding berries to can each year. We tried putting in a vegetable garden, using seaweed for fertilizer, but we gave it up as hopeless. We also tried keeping a cow, because fresh milk was a rarity. I shall never forget getting her there; you've never lived until you've shared a rowboat with a cow!

When playing we usually kept to the top part of the shore. ... None of us could swim. There was really no place to learn in the frigid Atlantic. ... Once I found a complete set of false teeth, which I treasured highly and kept on my dresser to admire. They disappeared one day, probably because my mother hadn't shared my enthusiasm.

On Dec. 29. 1916, Keeper Eugene Ingalls left Petit Manan in a powerboat to meet with his wife, Inez Robinson Ingalls, who was visiting with her parents at Moose Peak Light. Her father, Herbert Robinson, was the keeper there. Ingalls’ boat was lost in heavy seas; a search found the capsized boat but Ingalls’ body was never found.

Maizie Freeman Anderson grew up at Petit Manan, where her father James H. Freeman was keeper in the 1930s. She wrote about her childhood there for Down East magazine:

No trees grew in the shallow soil of Petit Manan, but there were patches of grass and a few hardy wildflowers grew in abundance, even among the rocks -- sweet pea, buttercups and others. We had a small cranberry bog yielding berries to can each year. We tried putting in a vegetable garden, using seaweed for fertilizer, but we gave it up as hopeless. We also tried keeping a cow, because fresh milk was a rarity. I shall never forget getting her there; you've never lived until you've shared a rowboat with a cow!

When playing we usually kept to the top part of the shore. ... None of us could swim. There was really no place to learn in the frigid Atlantic. ... Once I found a complete set of false teeth, which I treasured highly and kept on my dresser to admire. They disappeared one day, probably because my mother hadn't shared my enthusiasm.

Anderson remembered one particularly high tide when the entire island was under a foot of water. The chicken coops were floating in the cranberry bog. The family moved everything of value to the second floor of the house.

When Maizie Freeman Anderson was six years old she was taken by her father to Jonesboro for her first day of school. After an hour of school, Maizie was so homesick that she put her head on her desk and sobbed. She was let out early and was picked up by her father in the afternoon. She was grateful to return to her island home. "Up ahead was my island, and I watched the tower for the light. Soon it came, sending its beam out over the ocean as if to say, 'Welcome home.'" Anderson remembered small, rocky Petit Manan as "a paradise."

Left: Keeper James Freeman with his daughter Maizie and one of his sons, circa 1930s at Petit Manan.

Keeper Edward Pettegrow, who had barely escaped death in a 1928 storm at Avery Rock, was at Petit Manan in 1934. During a severe winter storm Keeper Pettegrow received a phone call from the nearby town of Corea asking him to be on the lookout for a missing lobsterman. About ten o'clock that night, the keeper saw a flaming torch in the distance, a distress signal from the lobster boat. Pettegrow called the vessel's position to two Coast Guard stations, but the storm worsened and a rescue seemed out of the question.

Left: Keeper James Freeman with his daughter Maizie and one of his sons, circa 1930s at Petit Manan.

Keeper Edward Pettegrow, who had barely escaped death in a 1928 storm at Avery Rock, was at Petit Manan in 1934. During a severe winter storm Keeper Pettegrow received a phone call from the nearby town of Corea asking him to be on the lookout for a missing lobsterman. About ten o'clock that night, the keeper saw a flaming torch in the distance, a distress signal from the lobster boat. Pettegrow called the vessel's position to two Coast Guard stations, but the storm worsened and a rescue seemed out of the question.

Thirty-six hours passed before the storm cleared and the lobsterman was feared lost. But at 9:00 a.m., the keepers sighted the vessel from the top of the lighthouse. Several seamen from Corea launched a boat and reached the lobsterman, finding him half-frozen but still alive. He miraculously survived and soon resumed his profession.

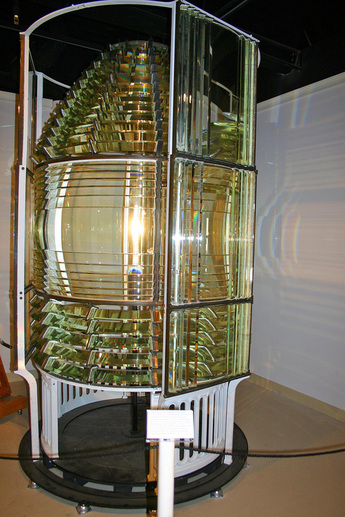

The second-order Fresnel lens at the Maine Lighthouse Museum

In The Maine Coast Louise Dickinson Rich told a humorous story about Petit Manan. A friend of the author, a native of Maine, was in Florida where she met a man from her home state. She asked how he liked Florida. "Too damn lonely," he said. She asked the man where he was from, "Steuben," the man replied.

The woman had spent much time in Steuben. "Thought I knew everyone in town," she told the man.

"Wal," he answered, "I ain't been in town much during the last 20 years. Been keepin' light out to Titm'nan. Be glad to get back, too. Too damn lonely here in Florida."

Rich explained that on Petit Manan the man knew where he was and why, so he wasn't lonely, just isolated.

Petit Manan Light was electrified in 1938. Coast Guardsman Jim Woods was the last officer in charge before the light was automated in 1972. He later shared some memories of the station:

It was a three-man crew with one off at a time. It consisted of a main house, three bedrooms, kitchen, living room, bathroom and office. The house was two stories high with a full cellar, and a generator room with three generators, with one running all the time. There were exposed fuel tanks and plenty of storage area in the generator room.

The light tower was about 100 or so feet from the main house. It was round with a spiral staircase to the light room and I once knew how many steps. The fog signal was an electric type. The boathouse was located at the cove side of the island. The boat used was a pea pod which was lowered to the water's edge via cable and a gasoline winch. Before you went out to the vessel (40-footer or 82-footer) you laid the pull line hooked to the winch handle alongside the boat ways so you could hook the boat and pull the line to engage the winch and be pulled up to the boathouse. Usually there were two men at the boathouse when receiving supplies and personnel.

The woman had spent much time in Steuben. "Thought I knew everyone in town," she told the man.

"Wal," he answered, "I ain't been in town much during the last 20 years. Been keepin' light out to Titm'nan. Be glad to get back, too. Too damn lonely here in Florida."

Rich explained that on Petit Manan the man knew where he was and why, so he wasn't lonely, just isolated.

Petit Manan Light was electrified in 1938. Coast Guardsman Jim Woods was the last officer in charge before the light was automated in 1972. He later shared some memories of the station:

It was a three-man crew with one off at a time. It consisted of a main house, three bedrooms, kitchen, living room, bathroom and office. The house was two stories high with a full cellar, and a generator room with three generators, with one running all the time. There were exposed fuel tanks and plenty of storage area in the generator room.

The light tower was about 100 or so feet from the main house. It was round with a spiral staircase to the light room and I once knew how many steps. The fog signal was an electric type. The boathouse was located at the cove side of the island. The boat used was a pea pod which was lowered to the water's edge via cable and a gasoline winch. Before you went out to the vessel (40-footer or 82-footer) you laid the pull line hooked to the winch handle alongside the boat ways so you could hook the boat and pull the line to engage the winch and be pulled up to the boathouse. Usually there were two men at the boathouse when receiving supplies and personnel.

My last days on Petit Manan were during the process of automation. The main light panels were removed for safe storage and future reassembly at the Shore Village Museum in Rockland, Maine, which has all kind of lighthouse lamps, horns, bells and sirens, all of which work and are in the capable hands of Chief Warrant Officer Ken Black, USCG Retired. After automation I was transferred to the CGC Spar, which at some time serviced all the light stations I had been stationed aboard.

The second-order Fresnel lens, almost ten feet high, is now at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland. A fog bell from Petit Manan is at the elementary school in the town of Milbridge.

DCB-224 aerobeacons replaced the Fresnel lens at the time of automation. The current optic is a VRB-25.

Catherine Thaxter, whose father was Keeper James H. Freeman, visited the Shore Village Museum (the forerunner of the Maine Lighthouse Museum) in Rockland in 1997. She examined the old Fresnel lens and told museum director Ken Black:

It made me sad to look at the lens. . . . I remember how my dad had cleaned it so often. I recall standing outside the tower at the lantern railing waiting for the sun to sink below the horizon, because the rules were that the sun wasn't lit until the last trace of sun was gone.

Catherine Thaxter donated an oil painting she did of Petit Manan Light Station to the Shore Village Museum.

Some repair work was carried out in 1997 by the Campbell Construction Group. The job included repointing, lead paint removal and cast iron restoration. In 1998 the company returned to the island to replace 11 decorative cast iron stair treads. The treads had been destroyed back in an 1869 storm (see above). The new treads perfectly match the original design.

After the light was automated, Petit Manan Island, except for the tower, was turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It became part of the 3,335-acre Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge, which included Petit Manan Point and parts of Bois Bubert and Nash islands. Petit Manan is now part of the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Puffin watch cruises out of Bar Harbor go close to Petit Manan Island for an excellent view of its feathered residents as well as the lighthouse. The tower can also be seen distantly from Petit Manan Point in the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge. The light remains an active aid to navigation.

DCB-224 aerobeacons replaced the Fresnel lens at the time of automation. The current optic is a VRB-25.

Catherine Thaxter, whose father was Keeper James H. Freeman, visited the Shore Village Museum (the forerunner of the Maine Lighthouse Museum) in Rockland in 1997. She examined the old Fresnel lens and told museum director Ken Black:

It made me sad to look at the lens. . . . I remember how my dad had cleaned it so often. I recall standing outside the tower at the lantern railing waiting for the sun to sink below the horizon, because the rules were that the sun wasn't lit until the last trace of sun was gone.

Catherine Thaxter donated an oil painting she did of Petit Manan Light Station to the Shore Village Museum.

Some repair work was carried out in 1997 by the Campbell Construction Group. The job included repointing, lead paint removal and cast iron restoration. In 1998 the company returned to the island to replace 11 decorative cast iron stair treads. The treads had been destroyed back in an 1869 storm (see above). The new treads perfectly match the original design.

After the light was automated, Petit Manan Island, except for the tower, was turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It became part of the 3,335-acre Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge, which included Petit Manan Point and parts of Bois Bubert and Nash islands. Petit Manan is now part of the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Puffin watch cruises out of Bar Harbor go close to Petit Manan Island for an excellent view of its feathered residents as well as the lighthouse. The tower can also be seen distantly from Petit Manan Point in the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge. The light remains an active aid to navigation.

Petit Manan Island supports a mixed tern colony of common terns, arctic terns and roseate terns. There is also a breeding colony of puffins as well as common eiders. In the 1980s and '90s, faculty and students from the College of the Atlantic, working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, restored and monitored populations of terns on the island and assisted in repairing the lighthouse station buildings. Fish and Wildlife staff use the tower as an observation post and live in the keeper's house.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Robert Upton (1817-?); (Robert Leighton (c. ?-1831); Patrick Campbell (c. 1831); Josiah Simpson (c. 1831-1833); John Simpson (c. 1833-1837); Moses Thompson (1838-1842); Richard C. Ray (1849-1853); Henry Tracy (1853-1854 and 1855-1860); John P. Small (1854-1855); Nathan D. Yeaton (1869-1872); George L. Upton (1876-1890); William D. Upton (1890-c. 1901); Charles A. Kenney (1903-1905); Frank L. Cotton (c. 1905); Almon Mitchell (c. 1905-1909); Eugene C. Ingalls (c. 1914-1916, died in service); Pierre A. Fagonde (c. 1929); James H. Freeman, first assistant, then keeper (1930-1940); Edwin A. Pettegrow (Pettegrew) (c. 1935)

Assistants: Amos Gay (c. 1830); George M. Small (c. 1855); Josiah W.R. Richardson, second assistant (1855); Darius Fickett, second assistant (1855); Alfred Moore (1855); Daniel Stanwood (1858); William Ray (1858-1859); Benjamin W. Means (1858-1860); Joseph W. Stover (1859); Eben Stanwood (1860); Stillman Parrott (1861-1871); Edwin K. Moore (1871-1872); Ezra D. Robinson (1872-?); John C. Noonan (1877, 1881); Frank W. Stevens, second assistant (1877, 1881); John Conners (1885-1886); William D. Upton, second assistant (1885-1890); James W. Kelley, second assistant (1886-1889); William D. Upton (c. 1885-1890); William C. Gott, second assistant (1889-1893); Fred W. Morong (1890-1895); Adelbert C. Leighton (1891-1896); Edmund Conners, (second assistant 1893-1896, first assistant 1896-1903); Edward D. Small, second assistant (1896-1897); Henry B. Collins (1897-1898); Edward Stevens Farren, second assistant (1898-1902); Otto A,. Wilson (c. 1905); Thomas A. Robinson, second assistant (c. 1905); Eugene Ingalls (1914-1916, died in service); Augustus S. Kelly (c. 1925-1931); Earle B. Ashby (assistant, c. 1929); Roscoe L. Fletcher (2nd assistant, 1928-1936), Arthur Marston (c. 1940s)

Coast Guard: Cecil Bryant (Officer in Charge, c. 1953-1954); Robert Brann (1953-1954); Arthur Howe (c. 1961); Richard Bassett (c. 1961); Henry Wiggins (c. 1961); Gus Chizmas (c. 1961); Richard Hennebury (1965-1967); Paul Muddy (c. late 1960s); Jim Woods (Officer in Charge, 1971-1972)

Robert Upton (1817-?); (Robert Leighton (c. ?-1831); Patrick Campbell (c. 1831); Josiah Simpson (c. 1831-1833); John Simpson (c. 1833-1837); Moses Thompson (1838-1842); Richard C. Ray (1849-1853); Henry Tracy (1853-1854 and 1855-1860); John P. Small (1854-1855); Nathan D. Yeaton (1869-1872); George L. Upton (1876-1890); William D. Upton (1890-c. 1901); Charles A. Kenney (1903-1905); Frank L. Cotton (c. 1905); Almon Mitchell (c. 1905-1909); Eugene C. Ingalls (c. 1914-1916, died in service); Pierre A. Fagonde (c. 1929); James H. Freeman, first assistant, then keeper (1930-1940); Edwin A. Pettegrow (Pettegrew) (c. 1935)

Assistants: Amos Gay (c. 1830); George M. Small (c. 1855); Josiah W.R. Richardson, second assistant (1855); Darius Fickett, second assistant (1855); Alfred Moore (1855); Daniel Stanwood (1858); William Ray (1858-1859); Benjamin W. Means (1858-1860); Joseph W. Stover (1859); Eben Stanwood (1860); Stillman Parrott (1861-1871); Edwin K. Moore (1871-1872); Ezra D. Robinson (1872-?); John C. Noonan (1877, 1881); Frank W. Stevens, second assistant (1877, 1881); John Conners (1885-1886); William D. Upton, second assistant (1885-1890); James W. Kelley, second assistant (1886-1889); William D. Upton (c. 1885-1890); William C. Gott, second assistant (1889-1893); Fred W. Morong (1890-1895); Adelbert C. Leighton (1891-1896); Edmund Conners, (second assistant 1893-1896, first assistant 1896-1903); Edward D. Small, second assistant (1896-1897); Henry B. Collins (1897-1898); Edward Stevens Farren, second assistant (1898-1902); Otto A,. Wilson (c. 1905); Thomas A. Robinson, second assistant (c. 1905); Eugene Ingalls (1914-1916, died in service); Augustus S. Kelly (c. 1925-1931); Earle B. Ashby (assistant, c. 1929); Roscoe L. Fletcher (2nd assistant, 1928-1936), Arthur Marston (c. 1940s)

Coast Guard: Cecil Bryant (Officer in Charge, c. 1953-1954); Robert Brann (1953-1954); Arthur Howe (c. 1961); Richard Bassett (c. 1961); Henry Wiggins (c. 1961); Gus Chizmas (c. 1961); Richard Hennebury (1965-1967); Paul Muddy (c. late 1960s); Jim Woods (Officer in Charge, 1971-1972)