History of Mayo's Beach Light, Wellfleet, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Wellfleet, with most of its land within the Cape Cod National Seashore and only about 3,500 year-round residents, is a reminder of the older, quieter Cape Cod.

The first Mayo's Beach Lighthouse. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

The town's well-protected harbor helped it develop as an important whaling port in the early 1700s, but that industry was curtailed by the Revolution. The town's primary business shifted to fishing and shellfishing, and Wellfleet oysters were eventually shipped all over the world.

The town's name comes from a similar location in England that was also known for its abundant oysters.

Wellfleet had a growing fishing fleet of about 100 vessels by the late 1830s. It was decided that a lighthouse on Mayo's Beach would aid mariners entering the harbor. There was some disagreement about this, as a lighthouse inspector felt that Billingsgate Light, at the entrance to the bay, was all that was needed in the vicinity.

The town's name comes from a similar location in England that was also known for its abundant oysters.

Wellfleet had a growing fishing fleet of about 100 vessels by the late 1830s. It was decided that a lighthouse on Mayo's Beach would aid mariners entering the harbor. There was some disagreement about this, as a lighthouse inspector felt that Billingsgate Light, at the entrance to the bay, was all that was needed in the vicinity.

The first lighthouse at the eastern end of Mayo's Beach consisted of a short wooden tower and octagonal lantern on the roof of a brick dwelling, with containing three rooms on the first floor and two rooms on a small second floor. Joseph Holbrook of Wellfleet was appointed first keeper at a salary of $350 yearly and the light went into service in 1838.

The second (1881) Mayo's Beach Lighthouse. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Ten oil lamps and accompanying 13-inch parabolic reflectors produced a fixed white light 21 feet above mean high water. Four of the lamps shone over the land only and were soon removed.

During Holbrook's first four years at the lighthouse there were three shipwrecks in the vicinity, including the 270-ton brig Diligence. In 1839, Holbrook counted over 700 vessels passing the station.

I. W. P. Lewis's landmark report on the area's lighthouses in 1843 included a statement by Holbrook, who painted a dire picture. The keeper complained that "The very wretched manner in which the house was built renders it almost uninhabitable; the walls always and the roof continually leaky."

Holbrook explained that the house, which had no foundation, was set two feet below the surface of the beach. This caused the cellar to be continually flooded with seawater.

During Holbrook's first four years at the lighthouse there were three shipwrecks in the vicinity, including the 270-ton brig Diligence. In 1839, Holbrook counted over 700 vessels passing the station.

I. W. P. Lewis's landmark report on the area's lighthouses in 1843 included a statement by Holbrook, who painted a dire picture. The keeper complained that "The very wretched manner in which the house was built renders it almost uninhabitable; the walls always and the roof continually leaky."

Holbrook explained that the house, which had no foundation, was set two feet below the surface of the beach. This caused the cellar to be continually flooded with seawater.

Two of Holbrook's children died in their first four years at the lighthouse, a tragedy that the keeper blamed on the unhealthy conditions. Holbrook believed that the lighthouse had been erected in a "very shameful manner."

Despite these conditions, the lighthouse was not rebuilt for nearly 40 years.

Stephen Pleasanton, the official in charge of the nation's lighthouses, recommended the discontinuance of Mayo's Beach Light in 1843, but it remained in operation. In 1857, the lighthouse received a Fresnel lens. A screen was later erected around the lantern to protect it from the birds that flew into it and broke the glass with regularity.

In 1865, William Atwood, who had lost an arm in the Civil War at Fredericksburg, became keeper at $350 per year. When Atwood died in 1876, his widow, Sarah, became keeper and continued to live at the station with their four children. Sarah Atwood remained keeper until 1891.

Stephen Pleasanton, the official in charge of the nation's lighthouses, recommended the discontinuance of Mayo's Beach Light in 1843, but it remained in operation. In 1857, the lighthouse received a Fresnel lens. A screen was later erected around the lantern to protect it from the birds that flew into it and broke the glass with regularity.

In 1865, William Atwood, who had lost an arm in the Civil War at Fredericksburg, became keeper at $350 per year. When Atwood died in 1876, his widow, Sarah, became keeper and continued to live at the station with their four children. Sarah Atwood remained keeper until 1891.

A new cast iron tower and brick and clapboard keeper's house were built in 1881, and the old buildings were removed.

The keeper's house is now a private home.

Charlie Turner, who also had a boat shop in Wellfleet, was the keeper for approximately the last 30 years of the light's active life. A dory of his own design was named after Turner, a prominent character in the town.

In his book Cape Cod Echoes, Earle Rich described a visit to Turner's boat shop. "Come in, you don't have to knock around here," Turner told the young Rich. "This is a boat shop, not a prayer meeting." A while later, Turner went to a window as the sun was setting, announcing, "She's getting pretty low. Guess I'll call it a day and get over there and get ready to light up for the night." He slipped on his favorite "beach jacket" and headed for the lighthouse for his nightly duties.

In his book Cape Cod Echoes, Earle Rich described a visit to Turner's boat shop. "Come in, you don't have to knock around here," Turner told the young Rich. "This is a boat shop, not a prayer meeting." A while later, Turner went to a window as the sun was setting, announcing, "She's getting pretty low. Guess I'll call it a day and get over there and get ready to light up for the night." He slipped on his favorite "beach jacket" and headed for the lighthouse for his nightly duties.

The kerosene-fueled lighthouse remained in service until it was discontinued on March 10, 1922. The light station property was sold at auction on August 1, 1923, to Capt. Harry Capron.

For many years, the general belief was that the lighthouse was destroyed after it was discontinued. Research at the National Archives by Colleen MacNeney (daughter of The Lighthouse People) in 2008 has proven that this was not the case.

Left: The circle next to the house indicates the former location of the lighthouse tower.

Left: The circle next to the house indicates the former location of the lighthouse tower.

As it turns out, the tower was dismantled and then shipped to California, where it replaced an earlier (1912) tower at Point Montara Light Station. It remains in use today.

The house and the 1907 oil house remain at Mayo's Beach, kept in pristine condition by the present owners. If you visit, be sure to respect the privacy of the owners.

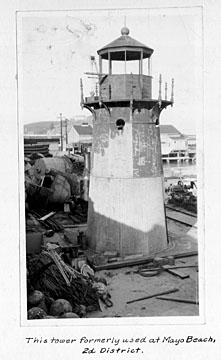

Right: The tower after it had been moved to California, before it went into service at the Point Montara station. Photo from U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Courtesy of Colleen MacNeney and the Shanklins.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Joseph Holbrook (1838-?), John Newcomb (?-1853), Freeman L. Hickman (1853-?), William Atwood (1865-1876), Sarah Atwood (1876-1891), James Smith (1891-?), Charles Turner (c. 1890s-1922)