History of Annisquam Harbor Lighthouse, Gloucester, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

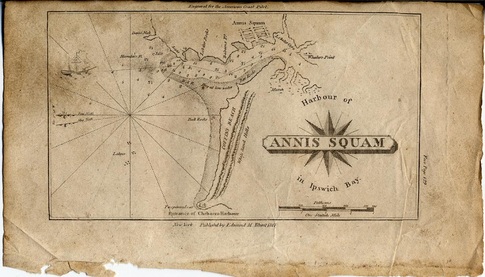

The Annisquam River, a saltwater estuary that's open to the ocean at both ends, separates most of Cape Ann -- and most of the city of Gloucester -- from the mainland.

The northern end of the river opens into Ipswich Bay, and the southern end connects to Gloucester Harbor via the Blynman Canal.

Cozy Annisquam village grew up on the east side of the river’s northern end beginning in 1631. The village grew into a fishing and shipbuilding center that rivaled Gloucester Harbor in its early days.

The Annisquam River was considered an important harbor of refuge for vessels traveling along the coast. Charles Boardman Hawes, in his book Gloucester by Land and Sea, illustrates this with the story of a sermon delivered by a fire-and-brimstone minister at the Isles of Shoals:

Suppose, my brethren, any of you should be taken short in the bay, in a northeast storm, your hearts trembling with fear, and nothing but death before you. Whither would your thoughts turn? What would you do?” he asked his congregation. One fisherman replied matter-of-factly, “Why, I should hoist the foresail and scud away for ’Squam.”

Cozy Annisquam village grew up on the east side of the river’s northern end beginning in 1631. The village grew into a fishing and shipbuilding center that rivaled Gloucester Harbor in its early days.

The Annisquam River was considered an important harbor of refuge for vessels traveling along the coast. Charles Boardman Hawes, in his book Gloucester by Land and Sea, illustrates this with the story of a sermon delivered by a fire-and-brimstone minister at the Isles of Shoals:

Suppose, my brethren, any of you should be taken short in the bay, in a northeast storm, your hearts trembling with fear, and nothing but death before you. Whither would your thoughts turn? What would you do?” he asked his congregation. One fisherman replied matter-of-factly, “Why, I should hoist the foresail and scud away for ’Squam.”

Congress appropriated $2,000 in April 1800 for a lighthouse at Wigwam Point, the northwesterly point of Annisquam village, where it would “best serve the purpose of discovering the entrance of Anesquam [a common early spelling] Harbor.”

The name Wigwam Point stems from the long use of the point as a summer gathering place for local Indians. Gustavus Griffin of Gloucester sold six and a half acres of land for the station to the government for $140.The first lighthouse was a 32-foot wooden tower, showing a fixed white light 40 feet above the water. A two-room, wood-frame keeper’s house was built near the tower.

James Day, a Gloucester native, was named the first keeper. In a letter in May 1805, Day wrote:

I the subscriber keeper of the Light House in Squam . . . being aged & infirm & not able to attend to my duty so far as I should wish, Do hereby express a desire to resign my office, & my son George Day having kept the Light under me ever since its establishment & assisted me in my duty relative thereto I would beg leave to recommend him as a fit & suitable person to take my place. & I hope he may be appointed, as I am confident he will at all times strictly & faithfully attend to his duty...My son is a good pilot for Squam harbour & for the ports in this neighbourhood & has at considerable hazard often assisted vessels in distress.

President Thomas Jefferson approved the appointment of George Day to succeed his father. An official noted at the time, "The son lives in the house where the light is kept & is always on the spot. His father seldom visits the place & is a mile from it & is now dangerously ill with a dropsy. His recommendation has been several months at Genl. Lincoln’s office Boston. The son has been the real keeper of the light for many years & it has been faithfully kept." George Day's initial salary as keeper was $200 yearly.

James Day, a Gloucester native, was named the first keeper. In a letter in May 1805, Day wrote:

I the subscriber keeper of the Light House in Squam . . . being aged & infirm & not able to attend to my duty so far as I should wish, Do hereby express a desire to resign my office, & my son George Day having kept the Light under me ever since its establishment & assisted me in my duty relative thereto I would beg leave to recommend him as a fit & suitable person to take my place. & I hope he may be appointed, as I am confident he will at all times strictly & faithfully attend to his duty...My son is a good pilot for Squam harbour & for the ports in this neighbourhood & has at considerable hazard often assisted vessels in distress.

President Thomas Jefferson approved the appointment of George Day to succeed his father. An official noted at the time, "The son lives in the house where the light is kept & is always on the spot. His father seldom visits the place & is a mile from it & is now dangerously ill with a dropsy. His recommendation has been several months at Genl. Lincoln’s office Boston. The son has been the real keeper of the light for many years & it has been faithfully kept." George Day's initial salary as keeper was $200 yearly.

Purported sea serpent sightings around Gloucester became front-page news in 1817 and 1818.

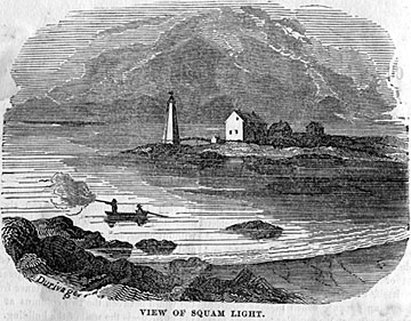

The 1851 lighthouse. Courtesy of Joseph Garland.

On August 17, 1818, the Boston Commercial Gazette reported the following, under the title “The Leviathan of the Deep”:

The famous Sea Serpent, was seen on the 16th inst. near Squam Light House, by many persons, some of whom were within twenty feet of him. He is now described as being ‘perfectly harmless, and might easily be caught.’ . . . The knowing ones in Boston have been computing the average amount which will be derived from an exhibition of the Sea Serpent. One hundred thousand dollars is the sum decided on!

The serpent was said to be more than 130 feet long and to pass through the water “with the rapidity of a meteor through the heavens.” On September 5 the Newport Mercury ran the exciting headline “The Sea Serpent—Taken!” The serpent had been captured by several people near the lighthouse, according to the story, after it had dragged their boat for two miles. The newspaper The Watch Tower soon reported the disappointing news that the appearance of the serpent was “very different from when it was alive and swimming.” The creature caught was a mere 10 feet long, with a head “of a hard scaly substance, which a harpoon cannot penetrate.” The undersized monster apparently never earned its captors the vast sums of money they had hoped for.

The famous Sea Serpent, was seen on the 16th inst. near Squam Light House, by many persons, some of whom were within twenty feet of him. He is now described as being ‘perfectly harmless, and might easily be caught.’ . . . The knowing ones in Boston have been computing the average amount which will be derived from an exhibition of the Sea Serpent. One hundred thousand dollars is the sum decided on!

The serpent was said to be more than 130 feet long and to pass through the water “with the rapidity of a meteor through the heavens.” On September 5 the Newport Mercury ran the exciting headline “The Sea Serpent—Taken!” The serpent had been captured by several people near the lighthouse, according to the story, after it had dragged their boat for two miles. The newspaper The Watch Tower soon reported the disappointing news that the appearance of the serpent was “very different from when it was alive and swimming.” The creature caught was a mere 10 feet long, with a head “of a hard scaly substance, which a harpoon cannot penetrate.” The undersized monster apparently never earned its captors the vast sums of money they had hoped for.

George Day was still in charge when the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis examined the station in 1842. By this time, the tower was in such bad shape that it was propped up with several wooden spars.

The second Annisquam Lighthouse, circa late 1800s

The keeper, whose pay had advanced to $350 yearly, provided the following statement for Lewis's 1843 report to Congress:

The frame of the tower is rotted in all parts, and has been shored up with spars for about twenty years. In heavy gales the tower is so shaken as to be very unsafe, and I hardly know what has kept it standing. Two years ago the walk or bridge leading from the house to the tower was swept away by a heavy sea only a few minutes after I crossed it. In winter the ice collects on the stairs so as to render passage up and down very dangerous. I expect every storm that comes the tower will be destroyed.

Day's statement went on to describe the deplorable condition of the dwelling. About 10 years earlier, rats had undermined the chimney.Lewis called the lighthouse "a local harbor beacon of exceeding usefulness to the fishermen," and said that it required "rebuilding entirely."

The 1801 lighthouse outlasted George Day's stay as keeper by a few months. William Dade became the light's keeper in 1850, and a new 40-foot octagonal wooden lighthouse tower was built during the following year. The original keeper's house was repaired and remained in use. It still stands today, enlarged and altered over the years.

The frame of the tower is rotted in all parts, and has been shored up with spars for about twenty years. In heavy gales the tower is so shaken as to be very unsafe, and I hardly know what has kept it standing. Two years ago the walk or bridge leading from the house to the tower was swept away by a heavy sea only a few minutes after I crossed it. In winter the ice collects on the stairs so as to render passage up and down very dangerous. I expect every storm that comes the tower will be destroyed.

Day's statement went on to describe the deplorable condition of the dwelling. About 10 years earlier, rats had undermined the chimney.Lewis called the lighthouse "a local harbor beacon of exceeding usefulness to the fishermen," and said that it required "rebuilding entirely."

The 1801 lighthouse outlasted George Day's stay as keeper by a few months. William Dade became the light's keeper in 1850, and a new 40-foot octagonal wooden lighthouse tower was built during the following year. The original keeper's house was repaired and remained in use. It still stands today, enlarged and altered over the years.

A fifth-order Fresnel lens, rotated by a clockwork mechanism, replaced the old lamps and reflector about 1857. A 109-foot covered walkway between the house and tower was added in 1867.

The covered walkway remained in place until some time after 1900, but a simple uncovered footbridge eventually replaced it.

Left: Annisquam Light in the late 19th century (U.S. Coast Guard)

Arthur G. Moore had a relatively short stay as keeper, from January 1 to September 1, 1872. Moore's wife died in May of that year, as mentioned in the keeper's log:

May 9, 1872: Lets in with moderate S. W. winds my Wife expired at six O clock this morning

May 11, 1872: Lets in Strong SE winds and rain today at half past two buried my Wife, and my peace ends this day

(Thanks to Bob Donovan and the Cape Ann Historical Association for these log excerpts.)

Dennison Hooper was keeper from 1872 to 1894. His son Edward was born at the lighthouse in 1879. On September 26, 1888, Edward Hooper later recalled, two schooners went aground on Coffin's Beach, across the mouth of the river from the lighthouse. One was the two-masted I. W. Hine. The crew of the Hine got ashore without assistance, and the schooner was refloated.

The other wreck that day was the Abbie B. Cranmer, a three-masted coal schooner from Baltimore that was heading for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The Cramer went ashore at the west end of Coffin's Beach. All hands had to hang on to the vessel's rigging all day as they waited for help. The crew of the Davis Neck Lifesaving Station arrived and tried to land a line for a breeches buoy, but they couldn't hit their target with several tries.

The Massachusetts Humane Society had kept a lifeboat at the lighthouse since the days of Keeper George Day. A group of volunteers took the lifeboat across the river to help the crew of the Cranmer. They had to land the boat on the west side of the river and then carry it two miles to the beach near the wreck. From there, they launched it into the surf and succeeded in rescuing the entire crew of the Cranmer. The schooner was a complete loss, and Hooper claimed that years later he could see wood from the schooner protruding from the sand at low tide.

Around 1890, a coal schooner from Bucksport, Maine -- the Mexican -- went ashore in a September northeaster about 150 yards north of the lighthouse. The crew managed to get ashore, abandoning the vessel, but the schooner was a total loss. "Many a resident of ''Squam made a saving on their coal bill that winter through the coal they salvaged as it came ashore," Edward Hooper later recalled.

In a 1966 letter to the Coast Guard, Edward Hooper recalled the supply boat’s yearly visits. Kerosene was delivered in five-gallon cans covered with wood, and a barrel of lime would be supplied to make whitewash for the tower. Keeper Hooper kept several cows in a barn at the station and sold milk in Annisquam village to help support his family. Edward recalled that he sometimes had to bring back the cows when they wandered away from the station at low tide. His father also kept an extensive garden and grapevines. In his later years at the station he rented adjacent vacant property for a larger garden and a place to keep his flock of chickens.

Dennison Hooper connected George Day’s old well to the house and installed a pump in the kitchen. A small second well provided water for the cows.

Left: Annisquam Light in the late 19th century (U.S. Coast Guard)

Arthur G. Moore had a relatively short stay as keeper, from January 1 to September 1, 1872. Moore's wife died in May of that year, as mentioned in the keeper's log:

May 9, 1872: Lets in with moderate S. W. winds my Wife expired at six O clock this morning

May 11, 1872: Lets in Strong SE winds and rain today at half past two buried my Wife, and my peace ends this day

(Thanks to Bob Donovan and the Cape Ann Historical Association for these log excerpts.)

Dennison Hooper was keeper from 1872 to 1894. His son Edward was born at the lighthouse in 1879. On September 26, 1888, Edward Hooper later recalled, two schooners went aground on Coffin's Beach, across the mouth of the river from the lighthouse. One was the two-masted I. W. Hine. The crew of the Hine got ashore without assistance, and the schooner was refloated.

The other wreck that day was the Abbie B. Cranmer, a three-masted coal schooner from Baltimore that was heading for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The Cramer went ashore at the west end of Coffin's Beach. All hands had to hang on to the vessel's rigging all day as they waited for help. The crew of the Davis Neck Lifesaving Station arrived and tried to land a line for a breeches buoy, but they couldn't hit their target with several tries.

The Massachusetts Humane Society had kept a lifeboat at the lighthouse since the days of Keeper George Day. A group of volunteers took the lifeboat across the river to help the crew of the Cranmer. They had to land the boat on the west side of the river and then carry it two miles to the beach near the wreck. From there, they launched it into the surf and succeeded in rescuing the entire crew of the Cranmer. The schooner was a complete loss, and Hooper claimed that years later he could see wood from the schooner protruding from the sand at low tide.

Around 1890, a coal schooner from Bucksport, Maine -- the Mexican -- went ashore in a September northeaster about 150 yards north of the lighthouse. The crew managed to get ashore, abandoning the vessel, but the schooner was a total loss. "Many a resident of ''Squam made a saving on their coal bill that winter through the coal they salvaged as it came ashore," Edward Hooper later recalled.

In a 1966 letter to the Coast Guard, Edward Hooper recalled the supply boat’s yearly visits. Kerosene was delivered in five-gallon cans covered with wood, and a barrel of lime would be supplied to make whitewash for the tower. Keeper Hooper kept several cows in a barn at the station and sold milk in Annisquam village to help support his family. Edward recalled that he sometimes had to bring back the cows when they wandered away from the station at low tide. His father also kept an extensive garden and grapevines. In his later years at the station he rented adjacent vacant property for a larger garden and a place to keep his flock of chickens.

Dennison Hooper connected George Day’s old well to the house and installed a pump in the kitchen. A small second well provided water for the cows.

There was much more open space around the light station in the nineteenth century than there is now, and Edward Hooper recalled that there was plenty of room for baseball games, played with baseballs made of “wound yarn covered with buttonhole stitching.”

The pastureland near the lighthouse—owned by George Norwood—was subdivided into house lots around 1900, and the settlement was named Norwood Heights.

The present 41-foot cylindrical brick lighthouse tower was built in 1897, on the same foundation as the previous two towers. Four years later the keeper’s house was renovated, a 3,000-foot wire fence was added along the boundary of the station, and a stone wall was built along the beach.

John W. Davis was keeper from 1894 to 1936, and he and his wife, Ida (Birch), saw many changes in their years at Annisquam. Telephone service and the city water supply reached the station in 1907. In 1922 the old fifth-order lens was replaced by a more powerful fourth-order lens, operated by electricity.

A foghorn was installed in 1931, but the following year it was decided that the signal would operate only from October 15 through May 15, so that local summer residents could have peaceful nights. In 1949 it went into operation in the summer, but only during the day.

In correspondence in 1997, Al Sherman of Delaware recalled life at Annisquam Light in the early 1950s, when his father was the Coast Guard keeper. Although the light—changed some years before from fixed to flashing—was powered with electricity, the mechanism that rotated the lens still needed to be wound by hand. “I can recollect memories of scaling the rocks beneath the light and most importantly going up the light every night with my dad to wind the turning mechanism,” Sherman said.

The present 41-foot cylindrical brick lighthouse tower was built in 1897, on the same foundation as the previous two towers. Four years later the keeper’s house was renovated, a 3,000-foot wire fence was added along the boundary of the station, and a stone wall was built along the beach.

John W. Davis was keeper from 1894 to 1936, and he and his wife, Ida (Birch), saw many changes in their years at Annisquam. Telephone service and the city water supply reached the station in 1907. In 1922 the old fifth-order lens was replaced by a more powerful fourth-order lens, operated by electricity.

A foghorn was installed in 1931, but the following year it was decided that the signal would operate only from October 15 through May 15, so that local summer residents could have peaceful nights. In 1949 it went into operation in the summer, but only during the day.

In correspondence in 1997, Al Sherman of Delaware recalled life at Annisquam Light in the early 1950s, when his father was the Coast Guard keeper. Although the light—changed some years before from fixed to flashing—was powered with electricity, the mechanism that rotated the lens still needed to be wound by hand. “I can recollect memories of scaling the rocks beneath the light and most importantly going up the light every night with my dad to wind the turning mechanism,” Sherman said.

The lighthouse was automated in 1974. The last keeper was removed, but the Coast Guard retained the buildings and 1.3 acres at the station to serve as housing for an officer and family.

Circa early 1900s view

After the devastating blizzard of February 1978, the wooden walkway between the house and tower was rebuilt.

Some repointing of the lighthouse was done in 1985. Inspections in the 1990s found that iron beams in the tower, installed to support a landing below the lantern level, had badly rusted, which caused the upper part of the tower to lift more than three inches. The beams needed to be replaced, along with about five to six feet of brickwork all the way around the tower.

Marsha Levy, a Coast Guard architect from Civil Engineering Unit Providence, completed the design work for the rehabilitation, and the Campbell Construction Group of Beverly, Massachusetts, carried out the work.

Some repointing of the lighthouse was done in 1985. Inspections in the 1990s found that iron beams in the tower, installed to support a landing below the lantern level, had badly rusted, which caused the upper part of the tower to lift more than three inches. The beams needed to be replaced, along with about five to six feet of brickwork all the way around the tower.

Marsha Levy, a Coast Guard architect from Civil Engineering Unit Providence, completed the design work for the rehabilitation, and the Campbell Construction Group of Beverly, Massachusetts, carried out the work.

Marty Nally and his crew removed and replaced about 3,000 bricks in the tower during the restoration, which was completed in August 2000.

Left: Contractor Marty Nally at the top of Annisquam Light. Carpenters work on the roof of the keeper's dwelling in the background.

As part of the restoration project, glass block windows—of recent vintage—in the tower were replaced with new ones, and the dwelling’s roof was replaced, using durable, wind-resistant shingles.

Some tour boats from Gloucester pass the lighthouse, and it can also be seen distantly from Wingaersheek Beach across the Annisquam River. There is no public access to the station itself.

As part of the restoration project, glass block windows—of recent vintage—in the tower were replaced with new ones, and the dwelling’s roof was replaced, using durable, wind-resistant shingles.

Some tour boats from Gloucester pass the lighthouse, and it can also be seen distantly from Wingaersheek Beach across the Annisquam River. There is no public access to the station itself.

Aerial views by Baystate Images

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

James Day (1801-1805); George Day (1805-1850); William Dade (1850-1853); Dominicus Poole (1853-1861); Nathaniel Parsons (1861-1866); Octavius Phipps (1866-1871); Mary Phipps (1871); Arthur G. Moore (1871-1872); Dennison Hooper (1872-1894); John W. Davis (1894-1936); Per Frederick Tornberg (1936-c. 1944); Francis R. Macy (c.1946-c.1948); Howard Ball (1951-1953); ? Sherman (c. early 1950s); William Dawe (c. 1955-?); Roy S. Pittsley (Coast Guard, c. 1955-c.1965); Armand E. Houde (Coast Guard, September 1965 to December 1967); James Deo (Coast Guard, 1972-1974)

James Day (1801-1805); George Day (1805-1850); William Dade (1850-1853); Dominicus Poole (1853-1861); Nathaniel Parsons (1861-1866); Octavius Phipps (1866-1871); Mary Phipps (1871); Arthur G. Moore (1871-1872); Dennison Hooper (1872-1894); John W. Davis (1894-1936); Per Frederick Tornberg (1936-c. 1944); Francis R. Macy (c.1946-c.1948); Howard Ball (1951-1953); ? Sherman (c. early 1950s); William Dawe (c. 1955-?); Roy S. Pittsley (Coast Guard, c. 1955-c.1965); Armand E. Houde (Coast Guard, September 1965 to December 1967); James Deo (Coast Guard, 1972-1974)