History of West Quoddy Head Light, Lubec, Maine

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

You can stand there on the rocks between the sea and the forest of spruce and fir and feel, backing you up, the whole expanse and power of this country, reaching away behind you to the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. It's quite a sensation.

-- Louise Dickinson Rich, The Coast of Maine.

The passage through all the rocky galleries of the Pine Tree Coast culminates at Quoddy Bay in a masterpiece.

-- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast.

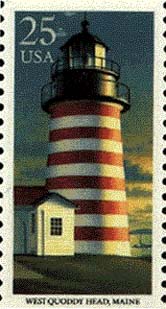

Red and white candy-striped West Quoddy Head Light is one of the most frequently depicted American lighthouses on calendars and posters. The picturesque lighthouse stands on the easternmost point of the United States mainland.

In 1806, a group of concerned citizens chose West Quoddy Head as a suitable place for a lighthouse to help mariners coming into the south entrance to Quoddy Roads, between the mainland and Campobello Island. According to some sources, Hopley Yeaton, an officer in the United States Revenue Cutter Service who is regarded as the father of the Coast Guard, played a role in the establishment of the station. Yeaton had retired to a farm in the area and was active in local affairs.

Congress appropriated $5000 for the light station on April 21, 1806. The contractors Beal and Thaxter built the first wooden lighthouse on the site, along with a small dwelling, in 1808. It was the first American lighthouse east of Penobscot Bay.

In 1806, a group of concerned citizens chose West Quoddy Head as a suitable place for a lighthouse to help mariners coming into the south entrance to Quoddy Roads, between the mainland and Campobello Island. According to some sources, Hopley Yeaton, an officer in the United States Revenue Cutter Service who is regarded as the father of the Coast Guard, played a role in the establishment of the station. Yeaton had retired to a farm in the area and was active in local affairs.

Congress appropriated $5000 for the light station on April 21, 1806. The contractors Beal and Thaxter built the first wooden lighthouse on the site, along with a small dwelling, in 1808. It was the first American lighthouse east of Penobscot Bay.

The first keeper was Thomas Dexter, at a salary of $250 per year. There was not enough soil near the lighthouse for a garden, so Dexter was forced to travel a great distance to Lubec to obtain all his food and supplies. His salary was raised in 1810 to $300.

Peter Godfrey, the second keeper, was at West Quoddy Head from 1813 until his death at age 82 in 1839. Godfrey’s job was complicated by the War of 1812, when British troops claimed control of the light station. Just a few miles away, the British occupied the town of Eastport for a lengthy portion of the war. An officer promised Godfrey that the British would pay him, but the salary was not forthcoming. The local customs inspector wrote a letter to the U.S. lighthouse authorities on Godfrey’s behalf, as he hadn’t been paid in several months and was “very poor” and had a “large family to support.”

At one time, West Quoddy Head, like Boston Light, had a fog cannon to warn mariners away from dangerous Sail Rocks nearby. The station received one of the nation's first fog bells in 1820.

It has been said that the Bay of Fundy is where fog is manufactured, and the keeper at West Quoddy Head had plenty of extra work operating the bell. Congress decided in 1827 that "the keeper of Quoddy Head Lighthouse, in the State of Maine, shall be allowed, in addition to his present salary, the sum of sixty dollars annually, for ringing the bell connected with said lighthouse, from the time he commenced ringing said bell."

At one time, West Quoddy Head, like Boston Light, had a fog cannon to warn mariners away from dangerous Sail Rocks nearby. The station received one of the nation's first fog bells in 1820.

It has been said that the Bay of Fundy is where fog is manufactured, and the keeper at West Quoddy Head had plenty of extra work operating the bell. Congress decided in 1827 that "the keeper of Quoddy Head Lighthouse, in the State of Maine, shall be allowed, in addition to his present salary, the sum of sixty dollars annually, for ringing the bell connected with said lighthouse, from the time he commenced ringing said bell."

Over the next 17 years, four different fog bells were tried at West Quoddy, but all of them were difficult to hear offshore. Even an unusual 14-foot steel bar was tried in place of a bell.

Sail Rocks with Grand Manan Island in the distance

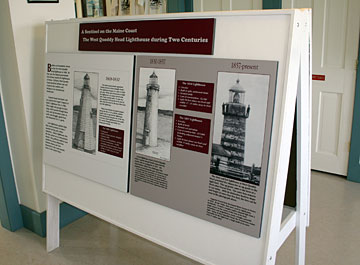

The first lighthouse was so poorly constructed that it required rebuilding by 1830. Congress appropriated $8000, and the contractor Joseph Berry rebuilt the tower in 1831 for $2350. The new rubblestone lighthouse, 49 feet tall, went into service on August 1, 1831.

Keeper Alfred Godfrey related some not-too-pretty details of life at West Quoddy in 1842 to I.W. P. Lewis for his important 1843 examination of the Lighthouse Establishment. Godfrey wrote:

My salary is $410 [yearly]. I have a family of seven persons. The climate here forbids the use of a garden or farm. My leisure time is occupied in boat building. I sometimes pilot vessels into Eastport, when no other pilot is at hand. Wrecks occur on the Sail rock as often as once a year... The dwelling house contains 6 rooms, kitchen, parlor and 4 chambers.

Keeper Alfred Godfrey related some not-too-pretty details of life at West Quoddy in 1842 to I.W. P. Lewis for his important 1843 examination of the Lighthouse Establishment. Godfrey wrote:

My salary is $410 [yearly]. I have a family of seven persons. The climate here forbids the use of a garden or farm. My leisure time is occupied in boat building. I sometimes pilot vessels into Eastport, when no other pilot is at hand. Wrecks occur on the Sail rock as often as once a year... The dwelling house contains 6 rooms, kitchen, parlor and 4 chambers.

The house leaks all about in rainy weather. The chimneys smoke badly . . . The tower is built of rubble stone, badly laid. In winter, the inside of the walls are coated with ice, from the effect of leakage . . .

The present 49-foot brick tower was erected in 1857, after a Congressional appropriation of $15,000. The new lighthouse received a third-order Fresnel lens. A one-and-one-half-story Victorian keeper's house was built at the same time.

West Quoddy Head Light's famous red and white stripes appear to have been added soon after the present tower was built. Red stripes on lighthouses were common in Canada, where it helped them stand out against snow. Only two other lighthouses in the United States -- Assateague Light in Virginia and Sapelo Island Light in Georgia -- have horizontal red and white stripes.

In 1869, a Daboll trumpet fog whistle was installed in place of the earlier bells. The signal was described as similar to the blast from a steam locomotive.

West Quoddy Head Light's famous red and white stripes appear to have been added soon after the present tower was built. Red stripes on lighthouses were common in Canada, where it helped them stand out against snow. Only two other lighthouses in the United States -- Assateague Light in Virginia and Sapelo Island Light in Georgia -- have horizontal red and white stripes.

In 1869, a Daboll trumpet fog whistle was installed in place of the earlier bells. The signal was described as similar to the blast from a steam locomotive.

The station was assigned an assistant keeper beginning in the 1850s. Ephraim N. Johnson, a native of the Washington County, Maine, town of Roque Bluffs, arrived as the assistant in 1900. When he advanced to principal keeper in 1905, Johnson’s pay was raised from $480 to $660 yearly.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

Johnson’s four children, and later his grandchildren, helped the keeper and his wife, Ada (Miller), with the chores at the station. Gwen Wasson, Johnson’s granddaughter, recalled some details of life at West Quoddy for an article by Ron Pesha in Lighthouse Digest:

He felt like a very rich man. He loved it, there on the ocean, doing what he wanted to do with his family around him. And we never lacked for food. Grandmother kept chickens and sometimes raised pigs.

Sometimes we went up the tower to assist polishing the brasswork. Grandfather said that you can’t leave any finger marks, because they collect dirt.

He felt like a very rich man. He loved it, there on the ocean, doing what he wanted to do with his family around him. And we never lacked for food. Grandmother kept chickens and sometimes raised pigs.

Sometimes we went up the tower to assist polishing the brasswork. Grandfather said that you can’t leave any finger marks, because they collect dirt.

Wasson recalled that Johnson always wore his official Lighthouse Service hat, even with his work clothes.

Left: Ephraim Johnson, courtesy of the West Quoddy Head Light Keepers Association.

The Johnsons were a well-loved family, known for their religious devotion. On Sunday afternoons, the family would gather around the pump organ in the parlor, with Ephraim’s deep bass voice leading the sing-alongs.

In Down East magazine Ruth L.W. Draper recalled visiting West Quoddy Head as a girl in the early 1900s:

The Johnsons were a well-loved family, known for their religious devotion. On Sunday afternoons, the family would gather around the pump organ in the parlor, with Ephraim’s deep bass voice leading the sing-alongs.

In Down East magazine Ruth L.W. Draper recalled visiting West Quoddy Head as a girl in the early 1900s:

The keeper of 'The Light,' Cap'n Ephie Johnson, and his wife Ada , were pure gold... Cap'n Ephie, his bronzed kindly face wrinkled at the eyes by many years of looking seaward, could predict the weather with utmost accuracy. . . . He'd say laconically, 'Land loom. Weather breeder. Rain tomorrow.' We scoffed, but sure enough the next day it would rain.

Right: A painting of Ephraim and Ada Johnson in the interpretive center at West Quoddy Head Light. Courtesy of the West Quoddy Head Light Keepers Association.

On one visit Ruth and a friend were awakened by the "fearsome shrieks" of the fog horn, which proceeded to blast for 56 straight hours. The girls escaped the sound by taking walks in the woods, where they found "masses of pitcher plants and an occasional fringed orchid."

In an article in Down East magazine, Ephraim Johnson’s grandson Philip Searles described a memorable day in 1929, when he was visiting with his grandparents during a school break. During breakfast, word arrived that a ship had gone aground about a mile south of the lighthouse in thick fog.

Johnson called the local Coast Guard station, and soon followed the assistant keeper, Eugene Larrabee, who ran down the shoreline with a supply of rope. Arriving at the scene of the disaster, Searles saw an enormous two-masted ship stuck in a crevice in the rocky cliff. Larrabee and another man were able to get a line to the ship, and the crewmen climbed one at a time onto the rocks, After the men were safely rescued, the ship slid off the rocks, and within minutes it was sunk out of sight except for the tips of its masts.

On one visit Ruth and a friend were awakened by the "fearsome shrieks" of the fog horn, which proceeded to blast for 56 straight hours. The girls escaped the sound by taking walks in the woods, where they found "masses of pitcher plants and an occasional fringed orchid."

In an article in Down East magazine, Ephraim Johnson’s grandson Philip Searles described a memorable day in 1929, when he was visiting with his grandparents during a school break. During breakfast, word arrived that a ship had gone aground about a mile south of the lighthouse in thick fog.

Johnson called the local Coast Guard station, and soon followed the assistant keeper, Eugene Larrabee, who ran down the shoreline with a supply of rope. Arriving at the scene of the disaster, Searles saw an enormous two-masted ship stuck in a crevice in the rocky cliff. Larrabee and another man were able to get a line to the ship, and the crewmen climbed one at a time onto the rocks, After the men were safely rescued, the ship slid off the rocks, and within minutes it was sunk out of sight except for the tips of its masts.

Searles also recalled his grandfather telling him tales of a pirate named Gulliver, who supposedly buried treasure not far from the lighthouse.

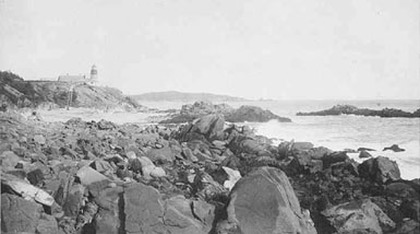

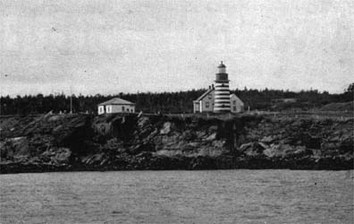

Circa 1900, from the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

Armed with a small shovel, young Searles dug enthusiastically at a location known as Gulliver’s Hole, in a cove about a half-mile from the light station. All he found was an occasional bottle or anchor chain, but Searles never gave up his belief that pirate loot was hidden in the vicinity.

Arthur Marston was an assistant keeper in the 1920s. His granddaughter, Jenine Marston Christensen, later recalled a conversation she had with Marston. While on a visit to the lighthouse, she asked him if the foghorn kept him awake. He replied, “Only when it stops!”

The keepers’ children had to walk about two miles to school in Lubec. One day in the 1920s, Marston’s children found some lumber that had washed ashore. One of the boys took the lumber and built a cabin in the woods that long served as a meeting place for local children and was still standing into the 1990s.

Arthur Marston was an assistant keeper in the 1920s. His granddaughter, Jenine Marston Christensen, later recalled a conversation she had with Marston. While on a visit to the lighthouse, she asked him if the foghorn kept him awake. He replied, “Only when it stops!”

The keepers’ children had to walk about two miles to school in Lubec. One day in the 1920s, Marston’s children found some lumber that had washed ashore. One of the boys took the lumber and built a cabin in the woods that long served as a meeting place for local children and was still standing into the 1990s.

Howard “Bob” Gray was the keeper from 1934 to 1952. His father, Joseph M. Gray, had been a keeper at Mount Desert Rock Light, Bass Harbor Head Light, and other Maine stations.

From "Stebbins Illustrated Coast Pilot," 1902

Bob Gray had the distinction of being the last civilian keeper and the first Coast Guard keeper at West Quoddy Head, as he joined the Coast Guard after they took over the management of the nation’s lighthouses in 1939. Gray’s image was immortalized in the September 22, 1945, cover illustration of the Saturday Evening Post; the painting by Stevan Dohanos portrayed the keeper tending the lawn near the base of the lighthouse.

Gray was fondly remembered in the publication 200 Years of Lubec History as a “sturdy, friendly man in shirtsleeves—even on a winter day.” It was said that Gray kept the lighthouse and fog signal building so clean you could eat off the floor, and he always had a welcoming smile for visitors. He was happy to give impromptu tours, and often invited visitors in for a cup of tea.

Gray was fondly remembered in the publication 200 Years of Lubec History as a “sturdy, friendly man in shirtsleeves—even on a winter day.” It was said that Gray kept the lighthouse and fog signal building so clean you could eat off the floor, and he always had a welcoming smile for visitors. He was happy to give impromptu tours, and often invited visitors in for a cup of tea.

During World War II, Gray’s daughters, Dorothy and Carolyn, and some friends found what appeared to be a bomb in the surf at a nearby beach.

They put the bomb in the back seat of Carolyn’s old Chevy and drove it home, over numerous bumps and potholes, to show their father. Gray told his children not to touch the bomb or to move the car, and he immediately phoned Washington.

Luckily, as Dorothy Gray Doble-Meyer explained in an article in Lighthouse Digest, it turned out the bomb wasn’t active; it was a German-made decoy.

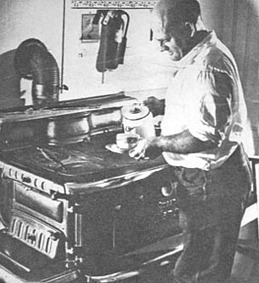

Left: Howard “Bob” Gray, seen here in the kitchen in the keeper’s house, was the keeper at West Quoddy Head Light 1934-52. Courtesy of the West Quoddy Head Light Keepers Association.

The last Coast Guard keeper at West Quoddy Head before its 1988 automation was Malcolm Rouse. Asked by the Boston Globe what he thought of automation, Rouse responded:

What I think you can't print. . . . It's the best duty a man can have for being with your family. I'm up when that sunshine hits here -- it's the first place it hits -- and oh, I'll miss that -- it sure is beautiful. It makes a pretty picture.

Click the audio file below to hear Malcolm Rouse, last Coast Guard keeper at West Quoddy Head Light, in an interview recorded in 1988.

Luckily, as Dorothy Gray Doble-Meyer explained in an article in Lighthouse Digest, it turned out the bomb wasn’t active; it was a German-made decoy.

Left: Howard “Bob” Gray, seen here in the kitchen in the keeper’s house, was the keeper at West Quoddy Head Light 1934-52. Courtesy of the West Quoddy Head Light Keepers Association.

The last Coast Guard keeper at West Quoddy Head before its 1988 automation was Malcolm Rouse. Asked by the Boston Globe what he thought of automation, Rouse responded:

What I think you can't print. . . . It's the best duty a man can have for being with your family. I'm up when that sunshine hits here -- it's the first place it hits -- and oh, I'll miss that -- it sure is beautiful. It makes a pretty picture.

Click the audio file below to hear Malcolm Rouse, last Coast Guard keeper at West Quoddy Head Light, in an interview recorded in 1988.

Lubec resident Maurice Babcock, Jr., whose father was the last civilian keeper of Boston Light, said about the pending automation: "It's like losing a species of animal or plant. Once it's gone, it's gone. All we'll have is a tower down there run by computer chips."

In 2004, the Campbell Construction Company was contracted by the Coast Guard to restore the lantern, at a cost of $176,000. The work included the replacement of some corroded parts of the lantern, the replacement of the lantern glass, and the removal of all lead paint. Drain spouts in the form of gargoyles (right) that had been removed many years earlier were replicated and installed, nearly returning the lighthouse close to its original appearance.

Michael Cyr of Saco Bay Castings recreated the gargoyles using an original piece at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland.

The lighthouse grounds are now part of Quoddy Head State Park. In 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the station became the property of the State of Maine. The light itself is still maintained by the Coast Guard as an active aid to navigation.

Michael Cyr of Saco Bay Castings recreated the gargoyles using an original piece at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland.

The lighthouse grounds are now part of Quoddy Head State Park. In 1998, under the Maine Lights Program, the station became the property of the State of Maine. The light itself is still maintained by the Coast Guard as an active aid to navigation.

Video of sunrise at West Quoddy Head Light, circa summer 1988.

A local group, the West Quoddy Head Light Keepers Association, has formed to enhance the experience of visitors to West Quoddy Head Light with exhibits and displays. A seasonal visitor center is now open in the former keeper's house.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

The grounds are open to the public and trails through the park wind along the shore and past the lighthouse.

Several species of whales can sometimes be seen offshore and bald eagles nest in the area. A visit to West Quoddy Head is well worth the trip.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Thomas Dexter (1808-1813); Peter Godfrey (1813-1839); Alfred Godfrey (1839-1842); Ebenezer Wormell (c. 1840s-50s); William Coggins (?-1856); David Joy (assistant, c. 1850s); Loring Leavitt (assistant, 1861-1867); Albert H. Godfrey (assistant, 1857-1861); William Godfrey (1856-1860); Loring A. Leavitt (assistant, 1861-1867); Richard Richardson (1860-1861); George A. Case (1861-1877); Lowell Chase (assistant, 1867-1878); Daniel Thayer (1877-1879); Joseph Huckins (assistant, 1878-1880); Henry M. Godfrey (1879-1882); Garrison Crowell (assistant, 1880-1882); William Fanning (1882-1886); Walter B. Mowry (assistant, 1882-1886); Alvin Eldrige (assistant, 1886-1887); John Connors (1886-1890); Henry M. Godfrey (assistant, 1887-1889); George W. Sabin (assistant, 1889-1890); John W. Guptill (1890-1899); Irwin Young (1890-1893); Edward L. Horn (assistant, 1893-1895); Edwin L. Eaton (assistant, 1895-1900); Fred M. Robbins (assistant, 1900-1901); Warren A. Murch (1899-1905); Herbert Robinson (assistant, 1905-1907); Eugene C. Ingalls (assistant, 1907-1912); Leo Allen (assistant, 1912-?); Ephraim N. Johnson (assistant 1901-1905, principal keeper 1905-1931); Ralph Temple Crowley (assistant? c.?1915?); Arthur Robie Marston (assistant, c. 1920s); Eugene N. Larrabee (c. 1935); Nelson Geel (?); Frank Mitchell (assistant, c. 1909-1911); Almon Mitchell (1909-1911); Leonard Bosworth Dudley (assistant, then principal keeper, 1909-1920); Hoyt Cheney (asst., c. 1950); Howard "Bob" Gray (1934-1952); Charles Robert Williams (Coast Guard Engineman First Class, 1952); Alex Sneddon (Coast Guard, c. 1952); Don Ashby (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Robert W. Brooks (Coast Guard Fireman First Class, c. early 1950s); Pat Stevens Bradisport (Summer 1956 Officer in Charge, Coast Guard); EN1 Paul Joseph Kessler (Coast Guard, 1954-1956); Russell Reilly (Coast Guard, c. 1960-1961); Dave Hardman (Coast Guard EN2, c. 1960-1961); Howard Johnson (Coast Guard SN, 1960-1962); John W. Willmott (c.1959-1961?, Coast Guard assistant/engineer); Stephen H. Rogers (c. 1962-1963, Coast Guard); Bruce Keene (1962-1964, Coast Guard); John Wiley Grandey II (Coast Guard, 1963-1964); Richard Copeland (1965, Coast Guard); Thomas Keene (1967, Coast Guard); Richard "Gary" Craig (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); BM1 Clifton Schofield (1975-1978, Coast Guard); BM1 Robert Marston (?-1975, Coast Guard); Ken Fisher (c. 1977, Coast Guard); David Blanding (c. 1977, Coast Guard); Paul Latour (Coast Guard, 1980); Dennis Everitt (Coast Guard, 1980); George Eaton (1978-1982, Coast Guard); Owen Gould (1982-1984, Coast Guard); John Richardson (1984-1988, Coast Guard); Malcolm Rouse (Coast Guard, 1988).

Several species of whales can sometimes be seen offshore and bald eagles nest in the area. A visit to West Quoddy Head is well worth the trip.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Thomas Dexter (1808-1813); Peter Godfrey (1813-1839); Alfred Godfrey (1839-1842); Ebenezer Wormell (c. 1840s-50s); William Coggins (?-1856); David Joy (assistant, c. 1850s); Loring Leavitt (assistant, 1861-1867); Albert H. Godfrey (assistant, 1857-1861); William Godfrey (1856-1860); Loring A. Leavitt (assistant, 1861-1867); Richard Richardson (1860-1861); George A. Case (1861-1877); Lowell Chase (assistant, 1867-1878); Daniel Thayer (1877-1879); Joseph Huckins (assistant, 1878-1880); Henry M. Godfrey (1879-1882); Garrison Crowell (assistant, 1880-1882); William Fanning (1882-1886); Walter B. Mowry (assistant, 1882-1886); Alvin Eldrige (assistant, 1886-1887); John Connors (1886-1890); Henry M. Godfrey (assistant, 1887-1889); George W. Sabin (assistant, 1889-1890); John W. Guptill (1890-1899); Irwin Young (1890-1893); Edward L. Horn (assistant, 1893-1895); Edwin L. Eaton (assistant, 1895-1900); Fred M. Robbins (assistant, 1900-1901); Warren A. Murch (1899-1905); Herbert Robinson (assistant, 1905-1907); Eugene C. Ingalls (assistant, 1907-1912); Leo Allen (assistant, 1912-?); Ephraim N. Johnson (assistant 1901-1905, principal keeper 1905-1931); Ralph Temple Crowley (assistant? c.?1915?); Arthur Robie Marston (assistant, c. 1920s); Eugene N. Larrabee (c. 1935); Nelson Geel (?); Frank Mitchell (assistant, c. 1909-1911); Almon Mitchell (1909-1911); Leonard Bosworth Dudley (assistant, then principal keeper, 1909-1920); Hoyt Cheney (asst., c. 1950); Howard "Bob" Gray (1934-1952); Charles Robert Williams (Coast Guard Engineman First Class, 1952); Alex Sneddon (Coast Guard, c. 1952); Don Ashby (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Robert W. Brooks (Coast Guard Fireman First Class, c. early 1950s); Pat Stevens Bradisport (Summer 1956 Officer in Charge, Coast Guard); EN1 Paul Joseph Kessler (Coast Guard, 1954-1956); Russell Reilly (Coast Guard, c. 1960-1961); Dave Hardman (Coast Guard EN2, c. 1960-1961); Howard Johnson (Coast Guard SN, 1960-1962); John W. Willmott (c.1959-1961?, Coast Guard assistant/engineer); Stephen H. Rogers (c. 1962-1963, Coast Guard); Bruce Keene (1962-1964, Coast Guard); John Wiley Grandey II (Coast Guard, 1963-1964); Richard Copeland (1965, Coast Guard); Thomas Keene (1967, Coast Guard); Richard "Gary" Craig (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); BM1 Clifton Schofield (1975-1978, Coast Guard); BM1 Robert Marston (?-1975, Coast Guard); Ken Fisher (c. 1977, Coast Guard); David Blanding (c. 1977, Coast Guard); Paul Latour (Coast Guard, 1980); Dennis Everitt (Coast Guard, 1980); George Eaton (1978-1982, Coast Guard); Owen Gould (1982-1984, Coast Guard); John Richardson (1984-1988, Coast Guard); Malcolm Rouse (Coast Guard, 1988).