History of Plum Beach Lighthouse, North Kingstown, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

"The Lighthouse presented images of sight and sound that conveyed a profound sense of beauty, security, dependability, and peace." - Lawrence H. Bradner, The Plum Beach Light: The Birth, Life and Death of a Lighthouse.

U.S. Coast Guard

The West Passage of Narragansett Bay, the most direct route from the south to Providence, Rhode Island, was bustling with vessels carrying coal and other freight in the late 1800s. Plum Beach Light was established to help mariners through this busy and dangerous area. Construction of the lighthouse was a great challenge, since the seas in the area were particularly rough.

During the building period a construction schooner lost anchorage and was swept down the passage, saved only by a cable near Beavertail. The contractor complained that Narragansett Bay was "the stormiest place we have ever worked."

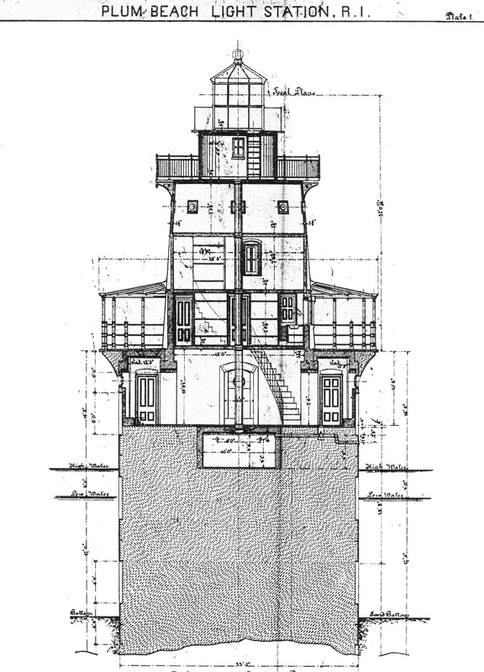

Plum Beach Light was one of a small number of American lighthouses built by the pneumatic caisson method. A massive wooden caisson topped with the first few courses of a cast-iron cylinder, 33 feet in diameter, was lowered to the floor of the bay. The water was pumped out of the caisson and workers entered it to dig into the bottom, allowing the structure to sink 30 feet into the floor of Narragansett Bay.

When the 54-foot cast-iron lighthouse was finished in 1899 there were not enough funds available for a lens, so for a time a temporary lantern was used. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed and illuminated on July 1, 1899. The revolving lens floated on a bed of mercury.

The Lighthouse Service had trouble staffing the lighthouse, as many keepers felt it to be a dangerous and isolated location.

Many visitors who came by boat to the lighthouse in the period from 1915 to 1925 were treated to tours given by Keeper Charlie Ormsby. These guests were impressed by the immaculate condition of the lighthouse and by the breathtaking view of the bay from the lantern room. Other visitors swam to the lighthouse, and eventually the "Lighthouse Swim" became an organized annual event.

The keepers augmented their diet with clams and quahogs dug at nearby Plum Beach Point and blueberries picked on the shore of Conanicut Island. For those who were strong enough to row back and forth to the mainland and were willing to endure the rough winters, Plum Beach Light was not a bad place to be a keeper.

In October 1916, Ormsby returned to the lighthouse after a three-day absence one day to find that 53-year-old assistant keeper John Boldt had died. The night before, passing mariners noted that the light had been burning very dimly, and they blew whistles and shined searchlights at the lighthouse in the hope of alerting the keeper. Boldt's death was attributed to heart failure; the New York native left two sons.

During the severe winter of 1918, people were able to drive vehicles across the frozen West Passage. The foundation of the lighthouse was badly cracked by the ice. Repairs were made in 1922 and 9,000 tons of riprap stone were added to prevent further damage.

The keepers augmented their diet with clams and quahogs dug at nearby Plum Beach Point and blueberries picked on the shore of Conanicut Island. For those who were strong enough to row back and forth to the mainland and were willing to endure the rough winters, Plum Beach Light was not a bad place to be a keeper.

In October 1916, Ormsby returned to the lighthouse after a three-day absence one day to find that 53-year-old assistant keeper John Boldt had died. The night before, passing mariners noted that the light had been burning very dimly, and they blew whistles and shined searchlights at the lighthouse in the hope of alerting the keeper. Boldt's death was attributed to heart failure; the New York native left two sons.

During the severe winter of 1918, people were able to drive vehicles across the frozen West Passage. The foundation of the lighthouse was badly cracked by the ice. Repairs were made in 1922 and 9,000 tons of riprap stone were added to prevent further damage.

At about 2:30 on the afternoon of September 21, 1938, Edwin S. Babcock, a substitute keeper, left in a dory to row ashore from Plum Beach Light. The seas were growing rough and Babcock was forced to return to the lighthouse.

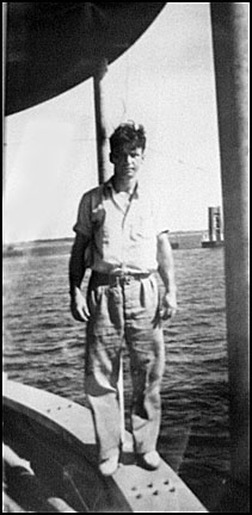

John O. Ganze, Courtesy of Alda Ganze Kaye.

John O. Ganze, assistant keeper, was in charge. It was becoming obvious that a major storm was on the way, so the two men secured all the windows and doors in the tower. Waves were soon pounding the lighthouse. Babcock looked out a window and saw a yacht passing by "at 60 miles per hour." Babcock later reported the yacht's occupants as dead, thinking they couldn't have survived. But they did survive, landing 200 feet inland on Fox Island, near Wickford.

The keepers took refuge in the fourth level of the lighthouse, only to see that wrecked boats and buildings were sweeping past them. The 30-foot waves broke open a door in the tower, washing away furniture and the station's boats.

The two men went as high as they could, to the fog bell room. There they lashed themselves, back to back, to the pipe that contained the weights for the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens. They felt a gigantic wave, possibly a tidal wave, strike the lighthouse. Finally, by early in the evening, the storm subsided.

It wasn't until the next morning that the men could get a clear picture of how lucky they were to be alive. Assistant Keeper Ganze used the light to signal the keeper at Whale Rock Light five miles away. There was no answer -- Whale Rock Light and its keeper were lost in the hurricane.

Seven people at lighthouses in the general area were killed in the hurricane of 1938, and several lighthouses were destroyed or irrevocably damaged. 262 people in the state of Rhode Island died in the storm. The hurricane reopened the old cracks in Plum Beach Light and did great damage to the entire structure.

The keepers took refuge in the fourth level of the lighthouse, only to see that wrecked boats and buildings were sweeping past them. The 30-foot waves broke open a door in the tower, washing away furniture and the station's boats.

The two men went as high as they could, to the fog bell room. There they lashed themselves, back to back, to the pipe that contained the weights for the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens. They felt a gigantic wave, possibly a tidal wave, strike the lighthouse. Finally, by early in the evening, the storm subsided.

It wasn't until the next morning that the men could get a clear picture of how lucky they were to be alive. Assistant Keeper Ganze used the light to signal the keeper at Whale Rock Light five miles away. There was no answer -- Whale Rock Light and its keeper were lost in the hurricane.

Seven people at lighthouses in the general area were killed in the hurricane of 1938, and several lighthouses were destroyed or irrevocably damaged. 262 people in the state of Rhode Island died in the storm. The hurricane reopened the old cracks in Plum Beach Light and did great damage to the entire structure.

In 1941 the completion of the first bridge between North Kingstown and Jamestown left Plum Beach Light obsolete. Birds took possession of the abandoned tower.

The lighthouse soon lost all its doors and windows and became badly rusted. The Coast Guard claimed that the lighthouse became state property by eminent domain, but the state denied ownership.

James Osborn was hired to paint the lighthouse in 1973. He became severely ill and suffered permanently blurred vision from exposure to the guano in the tower and filed a lawsuit against the state in 1984. The case was in and out of the courts for 14 years.

James Osborn was hired to paint the lighthouse in 1973. He became severely ill and suffered permanently blurred vision from exposure to the guano in the tower and filed a lawsuit against the state in 1984. The case was in and out of the courts for 14 years.

In 1988, a Massachusetts group planned to buy the lighthouse and moving it to Quincy, Massachusetts, where it was to be converted into a lighthouse museum.

A local woman, Shirley Silvia, felt the structure should stay put. Silvia and others founded the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse but made little progress due to the question of ownership. The structure continued to deteriorate, a battered hulk that seemed more an eyesore than a guardian.

In June 1998 a Superior Court ruled that the state "owned and controlled Plum Beach Lighthouse" at the times relevant to Osborn's suit. Three months later the suit was finally settled as the state awarded Osborn $42,000.

The settlement of the ownership issue cleared the way for the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse to acquire the lighthouse. In October 1999, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management transferred the deed for the 100-year-old structure to the nonprofit organization.

At the deed transfer ceremony, DEM Director Jan H. Reitsma said:

The determined efforts of the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc., have now paid off and will ensure that the lighthouse will continue to have an important place in Rhode Island's history.

Senator John Chafee was quoted in the press release for the transfer:

There are no better symbols of reliability, constancy and guidance than lighthouses... I'm proud to have played a role in this worthy endeavor, and I tip my hat to Shirley Silvia and the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc. Through their dogged persistence, they have made this day possible. Three cheers!

In June 1998 a Superior Court ruled that the state "owned and controlled Plum Beach Lighthouse" at the times relevant to Osborn's suit. Three months later the suit was finally settled as the state awarded Osborn $42,000.

The settlement of the ownership issue cleared the way for the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse to acquire the lighthouse. In October 1999, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management transferred the deed for the 100-year-old structure to the nonprofit organization.

At the deed transfer ceremony, DEM Director Jan H. Reitsma said:

The determined efforts of the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc., have now paid off and will ensure that the lighthouse will continue to have an important place in Rhode Island's history.

Senator John Chafee was quoted in the press release for the transfer:

There are no better symbols of reliability, constancy and guidance than lighthouses... I'm proud to have played a role in this worthy endeavor, and I tip my hat to Shirley Silvia and the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc. Through their dogged persistence, they have made this day possible. Three cheers!

In 1999 the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse received $500,000 under the Transportation Act for the 21st Century, known as TEA-21.

In August 2000 a team from Newport Collaborative Architects visited the lighthouse. A preliminary estimate of $955,000 for a complete restoration of the lighthouse, inside and out, was made in October 2000.

It was eventually decided to move forward with a restoration of the exterior first. In early 2003 a contract was awarded to the Abcore Restoration Company of Narragansett, RI, and work began in late June 2003.

Left: October 21, 1999 - The day of the deed transfer L to R: Jan Reitsma, DEM; Shirley Silvia, Dot Silva, George Silva, and Alda Kaye of the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse

It was eventually decided to move forward with a restoration of the exterior first. In early 2003 a contract was awarded to the Abcore Restoration Company of Narragansett, RI, and work began in late June 2003.

Left: October 21, 1999 - The day of the deed transfer L to R: Jan Reitsma, DEM; Shirley Silvia, Dot Silva, George Silva, and Alda Kaye of the Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse

An astonishing 52 tons of pigeon guano was removed from inside the tower with the help of Clean Harbors Environmental Services.

The Abcore crew under Keith Lescarbeau removed a half-inch layer of rust from the outside of the caisson and added reinforcing steel bands to the caisson to prevent further damage. The stone riprap around the caisson was also reinforced.

The upper gallery and its railing were repaired, new doors and windows installed, and eight new glass panels were installed in the lantern. The lighthouse has been repainted in its original color scheme with the lantern and caisson black while the tower is painted brown on its upper portion and white on the lower half. The Coast Guard approved the return of a light to the lighthouse, once again making it an active aid to navigation.

Right: Keith Lescarbeau of Abcore at work at Plum Beach Lighthouse. Photo by David Zapatka, courtesy of Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse.

The upper gallery and its railing were repaired, new doors and windows installed, and eight new glass panels were installed in the lantern. The lighthouse has been repainted in its original color scheme with the lantern and caisson black while the tower is painted brown on its upper portion and white on the lower half. The Coast Guard approved the return of a light to the lighthouse, once again making it an active aid to navigation.

Right: Keith Lescarbeau of Abcore at work at Plum Beach Lighthouse. Photo by David Zapatka, courtesy of Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse.

Plum Beach Light can be seen distantly from shore and as you're driving over the Jamestown-Verrazzano Bridge, but it is best viewed by boat.

To help with the ongoing preservation of Plum Beach Light, contact:

Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc. P.O.Box 1041 North Kingstown , RI, 02852

Left: The lighthouse toward the end of the 2003 renovation. Photo by David Zapatka, courtesy of Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse.

Below: 2009 TV news story on Plum Beach Light (WPRI)

Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse, Inc. P.O.Box 1041 North Kingstown , RI, 02852

Left: The lighthouse toward the end of the 2003 renovation. Photo by David Zapatka, courtesy of Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse.

Below: 2009 TV news story on Plum Beach Light (WPRI)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Joseph L. Eaton (1897-1899); Judson G. Allen (1899-1904); George Ehrhardt (1904-1911); George A. Troy (1911-1913); Charles L. Ormsby (c. 1915 - mid-1920s); Dosty Robarge (assistant, c. 1920s); "Moon" Mullins (c. 1920s); Edwin S. Babcock, substitute keeper (early 1920s - 1938); Reuben Phillips (late 1920s - c. 1938); John Otto Ganze, (assistant c. 1933-c. 1938, keeper c. 1938-1940).

Joseph L. Eaton (1897-1899); Judson G. Allen (1899-1904); George Ehrhardt (1904-1911); George A. Troy (1911-1913); Charles L. Ormsby (c. 1915 - mid-1920s); Dosty Robarge (assistant, c. 1920s); "Moon" Mullins (c. 1920s); Edwin S. Babcock, substitute keeper (early 1920s - 1938); Reuben Phillips (late 1920s - c. 1938); John Otto Ganze, (assistant c. 1933-c. 1938, keeper c. 1938-1940).