History of Prudence Island Lighthouse, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

When Rhode Island's founding father Roger Williams acquired the island and its smaller neighbors, he named them Prudence, Patience, and Hope. A tiny outcropping of rock between Hope and Patience received a more ominous name: Despair Island.

A catchy rhyme helped Rhode Island schoolchildren remember their local geography: "Prudence, Patience, Hope, and Despair. And little Hog Island right over there."

Prudence is roughly seven miles long and one and one-half miles across at its widest point. Given its prominence in the bay, it's surprising it took so long to establish a light station on the island. Nineteenth century ship traffic was heavy between Sandy Point, at the island's easternmost extremity, and Aquidneck Island, about a mile to the east.

The May 18, 1850, edition of the Bristol Phoenix reported:

The honorable Orin Fowler, of Massachusetts, presented in the House of Representatives, the petitions of citizens of Bristol, Warren, Newport, and Providence, Rhode Island; and of Fall River, Massachusetts; and of New York, praying that a beacon light-house be erected on Sandy Point, on Prudence Island, in Narragansett Bay. We trust that the prayer of these petitions will be granted, as the urgent necessity of a light-house at Sandy Point has long been seriously felt. It is required for all vessels navigating Narragansett and Mount Hope Bays. The New York bound steamers, which invariably pass the point, late in the evening or very early in the morning, require a light on this Point in order to enable them to pass on without detention, particularly, in thick weather.

Local lighthouse superintendent Edward W. Lawton recommended to Stephen Pleasanton, the fifth auditor of the Treasury who was in charge of the nation's lighthouses, that the 1823 lighthouse on Goat Island in Newport Harbor -- unused since 1842 -- be moved to Prudence Island and put in service there. Pleasanton concurred with this cost-saving suggestion.

The May 18, 1850, edition of the Bristol Phoenix reported:

The honorable Orin Fowler, of Massachusetts, presented in the House of Representatives, the petitions of citizens of Bristol, Warren, Newport, and Providence, Rhode Island; and of Fall River, Massachusetts; and of New York, praying that a beacon light-house be erected on Sandy Point, on Prudence Island, in Narragansett Bay. We trust that the prayer of these petitions will be granted, as the urgent necessity of a light-house at Sandy Point has long been seriously felt. It is required for all vessels navigating Narragansett and Mount Hope Bays. The New York bound steamers, which invariably pass the point, late in the evening or very early in the morning, require a light on this Point in order to enable them to pass on without detention, particularly, in thick weather.

Local lighthouse superintendent Edward W. Lawton recommended to Stephen Pleasanton, the fifth auditor of the Treasury who was in charge of the nation's lighthouses, that the 1823 lighthouse on Goat Island in Newport Harbor -- unused since 1842 -- be moved to Prudence Island and put in service there. Pleasanton concurred with this cost-saving suggestion.

In October 1851, the specifications were prepared for the new light station. By the end of October, contractor Horace Vaughn had moved the pieces of the tower to Prudence Island. Vaughn completed the reassembly of the tower in its new location by the end of November.

A new cast-iron deck and cast-iron "birdcage-style" lantern were installed atop the tower, along with lighting apparatus consisting of multiple oil lamps and parabolic reflectors. In 1856, a fifth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light would replace the antiquated equipment.

A six-room keeper's dwelling was constructed about 200 feet west of the lighthouse, with an elevated walkway leading from the house to the tower. The new light went into service for the first time on January 17, 1852, with Peleg Sherman its first keeper. In June 1853, Bristol native Henry Dimond replaced Sherman.

Isaac Aldrich was the keeper when a fog bell and striking machinery were installed in a wooden tower in 1885. A boathouse was added in 1895, when Thomas Burke was in charge.

Martin Thompson, originally from Norway, became keeper in 1905 after stints as an assistant at Sakonnet Light, Rhode Island, and Borden Flats Light at Fall River, Massachusetts.

A six-room keeper's dwelling was constructed about 200 feet west of the lighthouse, with an elevated walkway leading from the house to the tower. The new light went into service for the first time on January 17, 1852, with Peleg Sherman its first keeper. In June 1853, Bristol native Henry Dimond replaced Sherman.

Isaac Aldrich was the keeper when a fog bell and striking machinery were installed in a wooden tower in 1885. A boathouse was added in 1895, when Thomas Burke was in charge.

Martin Thompson, originally from Norway, became keeper in 1905 after stints as an assistant at Sakonnet Light, Rhode Island, and Borden Flats Light at Fall River, Massachusetts.

Thompson would stay at the lighthouse until 1933 -- longer than anyone in the station's history.

In February 1913, a newspaper article described a thrilling adventure experienced by Keeper Thompson's two young daughters. According to the story, Thompson sighted what he believed to be a seal several hundred yards offshore, and his daughters, Nellie and Bessie, rowed out to investigate. The girls soon became frightened when they realized the animal was much larger than the harbor seals usually seen in the vicinity. It also had tusks two feet long.

As the formidable creature started toward them, the girls rowed for all they were worth back to the island. They made it back safely, and the animal -- a walrus, according to the newspaper account -- swam back into open water. Atlantic walruses were once plentiful as far south as Cape Cod, but hunting had mostly wiped them out of New England by the early 1800s. This particular specimen had apparently strayed far from its herd.

Left: Keeper Martin Thompson. Courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association

As the formidable creature started toward them, the girls rowed for all they were worth back to the island. They made it back safely, and the animal -- a walrus, according to the newspaper account -- swam back into open water. Atlantic walruses were once plentiful as far south as Cape Cod, but hunting had mostly wiped them out of New England by the early 1800s. This particular specimen had apparently strayed far from its herd.

Left: Keeper Martin Thompson. Courtesy of the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association

The worst hurricane in the recorded history of New England hit the coast on September 21, 1938.

U.S. Coast Guard

Here a description of what took place in Keeper George T. Gustavus' own words, as told to historian Edward Rowe Snow for his book A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod:

The station dwelling was on the low level at the Sandy Point. Many summer folk had cottages near and around the Light dwelling; our nearest neighbor, retired Keeper Thompson, who had been stationed at this light for 25 years, had a nice little cottage next to the Station dwelling called the "Snug-Harbor."

On the day of the storm, he and Mr. and Mrs. Lynch, summer folk, came rushing into the Station dwelling. Mr. Thompson [former keeper Martin Thompson] said that he had lived there for 25 years and that the house would stand any blow that would strike.

The station dwelling was on the low level at the Sandy Point. Many summer folk had cottages near and around the Light dwelling; our nearest neighbor, retired Keeper Thompson, who had been stationed at this light for 25 years, had a nice little cottage next to the Station dwelling called the "Snug-Harbor."

On the day of the storm, he and Mr. and Mrs. Lynch, summer folk, came rushing into the Station dwelling. Mr. Thompson [former keeper Martin Thompson] said that he had lived there for 25 years and that the house would stand any blow that would strike.

Those folks, my wife and son and I were caught inside by the tidal wave and after two 17-foot seas of water along with plenty of wind hit, we were caught like rats in a trap.

We all rushed upstairs, when the house broke up we were all thrown into the rushing waters - I found myself inside a cottage on the Island about 1/2 mile from where the station dwelling had been. A lad living on the Island followed me down the shore. When he saw me near the cliffs, he stuck a timber down into the water and I clamped the death grip on it. Then he and others hauled me out.

I was the only member that got out of that dwelling alive - my wife was found a few days later on the beach near Newport. I never found the boy. Keeper Thompson, Mr. and Mrs. Lynch were found on the Island shores about a week later. The first thing we done after getting out, was to see that the light was attended. We strung a wire from the Electric Light building that was near the light station and got a light going; then I began looking for the wife and son, whom the neighbors informed were safe and taken care of. I knew better. They told me the next day how things really stood.

Left: Keeper George T. Gustavus, courtesy of Joan Kenworthy

I was the only member that got out of that dwelling alive - my wife was found a few days later on the beach near Newport. I never found the boy. Keeper Thompson, Mr. and Mrs. Lynch were found on the Island shores about a week later. The first thing we done after getting out, was to see that the light was attended. We strung a wire from the Electric Light building that was near the light station and got a light going; then I began looking for the wife and son, whom the neighbors informed were safe and taken care of. I knew better. They told me the next day how things really stood.

Left: Keeper George T. Gustavus, courtesy of Joan Kenworthy

When the Coast Guard cutter Tahoe arrived at Prudence Island after the storm, an officer called to someone on shore, "Where are the dead?" The person replied, "All washed to sea." Five people died at Prudence Island in the disaster that killed over 700 across New England.

Right: Keeper George T. Gustavus and his family, courtesy of Joan Kenworthy. The keeper's wife, Mabel, is next to him in the front row; their youngest son, Edward, is at the front left.

Milton Chase lived in a large house just north of the lighthouse, and he operated the island's electric plant. On the night of the hurricane, Chase ran a cable from the power station to the lighthouse. He got a light bulb operating in the lantern that night -- the first time the lighthouse operated on electric power.

The light remained active after the hurricane, with Milton Chase briefly serving as acting keeper. In 1939, a fourth-order lens was installed and the light was electrified, and Chase's job title was changed to "lamplighter." During World War II, Sarah Chase, Milton's wife, served as lamplighter. When Milton Chase died in 1958, Rodger C. Grant took over as lamplighter. Michael Bachini got the job in 1961.

Milton Chase lived in a large house just north of the lighthouse, and he operated the island's electric plant. On the night of the hurricane, Chase ran a cable from the power station to the lighthouse. He got a light bulb operating in the lantern that night -- the first time the lighthouse operated on electric power.

The light remained active after the hurricane, with Milton Chase briefly serving as acting keeper. In 1939, a fourth-order lens was installed and the light was electrified, and Chase's job title was changed to "lamplighter." During World War II, Sarah Chase, Milton's wife, served as lamplighter. When Milton Chase died in 1958, Rodger C. Grant took over as lamplighter. Michael Bachini got the job in 1961.

The last lamplighter was Marcy (Taber) Bachini Dunbar, whose brother, George Taber, had rescued Keeper Gustavus in the hurricane. Marcy replaced her husband, Michael Bachini, following his death in 1969.

Left: Wreckage near the lighthouse after the hurricane of 1938.

After the automation of the light in 1972, members of the Coast Guard's aids to navigation team in Bristol visited it periodically. Island residents often performed basic maintenance, cleaning up the grounds around the lighthouse and occasionally replacing a broken windowpane. From the time of its founding in 1987, members of a group called the Prudence Conservancy did much of this work.

After the automation of the light in 1972, members of the Coast Guard's aids to navigation team in Bristol visited it periodically. Island residents often performed basic maintenance, cleaning up the grounds around the lighthouse and occasionally replacing a broken windowpane. From the time of its founding in 1987, members of a group called the Prudence Conservancy did much of this work.

The Prudence Conservancy's involvement led to the granting of a license by the Coast Guard for the group to officially take over the care of the tower, largely due to the work of Marge Del Papa, a board member of the organization. A ceremony was held to celebrate the license agreement on August 11, 2001.

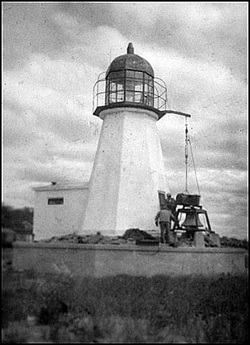

Undated U.S. Coast Guard photo, circa 1950s.

More recently volunteers have shored up the foundation and repainted the tower. One of those who has helped is Prudence Island resident Kevin Blount, formerly the officer in charge of the Coast Guard's Aids to Navigation team that worked on the light.

Prudence Island Light remains an active aid to navigation, now fitted with a 250-millimeter modern lens showing a green flash every six seconds. The old-style "birdcage" style lantern is the one of very few still in use in the U.S., and the lighthouse tower is the oldest in the state.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Peleg Sherman (1852-1853), Henry Dimond (1853-1855), Edward W. Spooner (1855-1859), William S. W. Yewel (1859-1862), Thomas J. Corey (1862-1875), Isaac Aldrich (1875-1886), John T. Clarke (1886-1887), Onley Coyle (1887-1888), John F. Follett (1888-1889), Thomas Burke (1894-1898), Nathaniel Dodge (1898-1905), Martin Thompson (1905-1933), Elmer V. Newton (1933-1937), George T. Gustavis (1937-1938), Milton H. Chase (lamplighter, 1939-1943), Sarah A. Chase (lamplighter, 1943-1951), Milton H. Chase (lamplighter, 1951-1958), Roger C. Grant (lamplighter, 1958-1961), Michael J. Bachini (lamplighter, 1961-1969), Marcy (Taber) Bachini Dunbar (lamplighter, 1969-1972)

Prudence Island Light remains an active aid to navigation, now fitted with a 250-millimeter modern lens showing a green flash every six seconds. The old-style "birdcage" style lantern is the one of very few still in use in the U.S., and the lighthouse tower is the oldest in the state.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Peleg Sherman (1852-1853), Henry Dimond (1853-1855), Edward W. Spooner (1855-1859), William S. W. Yewel (1859-1862), Thomas J. Corey (1862-1875), Isaac Aldrich (1875-1886), John T. Clarke (1886-1887), Onley Coyle (1887-1888), John F. Follett (1888-1889), Thomas Burke (1894-1898), Nathaniel Dodge (1898-1905), Martin Thompson (1905-1933), Elmer V. Newton (1933-1937), George T. Gustavis (1937-1938), Milton H. Chase (lamplighter, 1939-1943), Sarah A. Chase (lamplighter, 1943-1951), Milton H. Chase (lamplighter, 1951-1958), Roger C. Grant (lamplighter, 1958-1961), Michael J. Bachini (lamplighter, 1961-1969), Marcy (Taber) Bachini Dunbar (lamplighter, 1969-1972)