History of Owls Head Light, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Owl's Head ushers at once upon a scene almost too beautiful to profane with speech when we are looking at it, impossible to find language to do it justice when memory would summon it before us again. -- Samuel Adams Drake, The Pine Tree Coast, 1891.

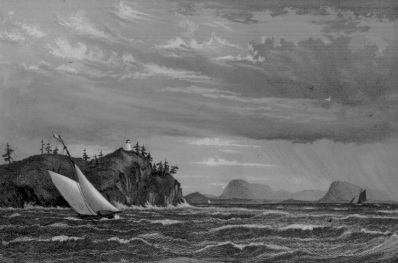

Owls Head Light c. 1859 (National Archives)

Nobody is quite sure how Owl's Head got its name. Some say the picturesque promontory resembles an owl from the water, but it takes great imagination to see anything of the sort. Some say Owl's Head is the English translation of the Indian name for the spot, Medadacut.

When Owl's Head was visited by Samuel de Champlain in 1605, it was known as Bedabedec Point, an Indian word meaning "Cape of the Winds." The village called Owl's Head became a town in 1921; it had previously been part of South Thomaston.

The growing lime trade in nearby Rockland and Thomaston led to the establishment of a light station at Owl's Head, at the entrance to Rockland Harbor. President John Quincy Adams authorized the building of Owl's Head Light in 1825.

A tall lighthouse was not necessary because of the height of the promontory. The light is exactly 100 feet above sea level. Although many sources claim that the 1825 tower still stands, the present lighthouse replaced the original one in 1852. Restoration work by the American Lighthouse Foundation and the J.B. Leslie Masonry Company in 2010, along with research by J. Candace Clifford, confirmed this fact.

When Owl's Head was visited by Samuel de Champlain in 1605, it was known as Bedabedec Point, an Indian word meaning "Cape of the Winds." The village called Owl's Head became a town in 1921; it had previously been part of South Thomaston.

The growing lime trade in nearby Rockland and Thomaston led to the establishment of a light station at Owl's Head, at the entrance to Rockland Harbor. President John Quincy Adams authorized the building of Owl's Head Light in 1825.

A tall lighthouse was not necessary because of the height of the promontory. The light is exactly 100 feet above sea level. Although many sources claim that the 1825 tower still stands, the present lighthouse replaced the original one in 1852. Restoration work by the American Lighthouse Foundation and the J.B. Leslie Masonry Company in 2010, along with research by J. Candace Clifford, confirmed this fact.

The president and Fifth Auditor Stephen Pleasanton, in charge of lighthouses, clashed over the appointment of the first keeper. President Adams' candidate of course won out, and Isaac Stearns (sometimes spelled "Sterns") became the first keeper at $350 per year.

Stearns, a Massachusetts native and a veteran of the War of 1812, was 32 years old when the light went into service. He and his wife, Lucy, had three sons and three daughters. Once, when Lucy Stearns went to the lighthouse to trim the wicks, she was knocked from the summit by a gust of wind and narrowly escaped being blown into the sea. In spite of the dangers, a system of walkways and stairs leading from the dwelling to the lighthouse wasn’t added until 1874.

The original lamps and reflectors were replaced by a fourth-order Fresnel lens in 1856, and the lens remains in use today.

In 1831, Captain Derby of the Revenue Cutter Morris proclaimed the lighthouse “the most miserable one on the whole coast.” He reported that the mortar was “nothing but sand,” and that stones were dropping out. He feared the tower wouldn’t stand much longer. Repairs were carried out in 1832, but the station was in deplorable condition when I. W. P. Lewis visited for his important report to Congress in 1843. The interior of the tower was coated with ice in winter and was generally “in a filthy state.” Ten panes of glass were broken in the wrought-iron lantern, and the lamps and reflectors were out of alignment. The dwelling was just as bad, with bad mortar, a leaky roof, and badly cracked walls.

The original lamps and reflectors were replaced by a fourth-order Fresnel lens in 1856, and the lens remains in use today.

In 1831, Captain Derby of the Revenue Cutter Morris proclaimed the lighthouse “the most miserable one on the whole coast.” He reported that the mortar was “nothing but sand,” and that stones were dropping out. He feared the tower wouldn’t stand much longer. Repairs were carried out in 1832, but the station was in deplorable condition when I. W. P. Lewis visited for his important report to Congress in 1843. The interior of the tower was coated with ice in winter and was generally “in a filthy state.” Ten panes of glass were broken in the wrought-iron lantern, and the lamps and reflectors were out of alignment. The dwelling was just as bad, with bad mortar, a leaky roof, and badly cracked walls.

Penly Haines had been keeper since July 1841. In a statement for Lewis, he described the tower as “in a state of entire dilapidation and decay, from top to bottom.” The dwelling had been repaired only two years earlier, but Haines reported that it was “all falling to pieces.” The kitchen, he feared, would soon collapse if not repaired.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

It appears that no significant improvements had been made by an August 1850 inspection, which reported, “Tower is in a bad state, and the lantern rusted very much. . . Dwelling-house also wants to be new.”

One of the most memorable events in the history of Owl's Head Light took place during the storm of December 22, 1850. Five vessels went aground in this storm between Rockland Harbor and Spruce Head. At nearby Jameson's Point, a small schooner from Massachusetts was anchored. The captain had gone ashore, leaving the mate, Richard B. Ingraham, a seaman named Roger Elliott, and one passenger, Lydia Dyer, who was engaged to Ingraham. The packet was to start for Boston the next morning.

Near midnight the storm intensified. The cables holding the vessel snapped and the schooner headed across the Penobscot Bay toward Owl's Head. It quickly smashed into the rocky ledges south of the lighthouse. The three on board huddled together on the deck and were soon practically frozen in the surf. They pulled blankets around themselves in an effort to stay dry.

As the schooner broke apart, Elliott escaped the vessel and managed to climb over the ice-covered rocks to the shore. Practically dead from exhaustion, he reached the road to the lighthouse. The keeper happened to be driving by in a sleigh, and he took the dazed Elliott to the keeper's house where he gave him hot rum and put him in bed. Barely able to speak, Elliott was able to tell the keeper about the others still on the schooner. A dozen men were rounded up, and they headed for the shore.

One of the most memorable events in the history of Owl's Head Light took place during the storm of December 22, 1850. Five vessels went aground in this storm between Rockland Harbor and Spruce Head. At nearby Jameson's Point, a small schooner from Massachusetts was anchored. The captain had gone ashore, leaving the mate, Richard B. Ingraham, a seaman named Roger Elliott, and one passenger, Lydia Dyer, who was engaged to Ingraham. The packet was to start for Boston the next morning.

Near midnight the storm intensified. The cables holding the vessel snapped and the schooner headed across the Penobscot Bay toward Owl's Head. It quickly smashed into the rocky ledges south of the lighthouse. The three on board huddled together on the deck and were soon practically frozen in the surf. They pulled blankets around themselves in an effort to stay dry.

As the schooner broke apart, Elliott escaped the vessel and managed to climb over the ice-covered rocks to the shore. Practically dead from exhaustion, he reached the road to the lighthouse. The keeper happened to be driving by in a sleigh, and he took the dazed Elliott to the keeper's house where he gave him hot rum and put him in bed. Barely able to speak, Elliott was able to tell the keeper about the others still on the schooner. A dozen men were rounded up, and they headed for the shore.

The rescue party soon found the schooner and got on board. There they found a block of ice enveloping Ingraham and Dyer. From all appearances the couple was dead, but the rescue party was determined to leave nothing to chance. The men brought the block to the kitchen of the keeper's house. They chipped the ice away, keeping the pair in cold water. Then they slowly raised the temperature of the water and began to exercise the limbs of the victims. After almost two hours of this massaging and exercising, Lydia Dyer showed signs of life. An hour later Ingraham opened his eyes and said, "What is all this? Where are we?"

By the next day Dyer and Ingraham were able to eat, but it was months before they were fully recovered. They eventually married and had four children. Roger Elliott never fully recovered, but his struggle to reach safety had resulted in the rescue of the other two. Lydia Dyer and Richard Ingraham will always be celebrated as the "Frozen Couple of Owl's Head."

The tower was rebuilt in 1852, and a new wood-frame one-and-one-half-story dwelling was finally built in 1854. Construction specifications published when the lighthouse tower was rebuilt stated, “The tower to be built of the best hard burnt brick, the form round, the foundation to be sunk as deep as may be necessary to make the whole fabric perfectly secure and all of the bricks to be laid in the best of Rosendale cement.”

The tower was rebuilt in 1852, and a new wood-frame one-and-one-half-story dwelling was finally built in 1854. Construction specifications published when the lighthouse tower was rebuilt stated, “The tower to be built of the best hard burnt brick, the form round, the foundation to be sunk as deep as may be necessary to make the whole fabric perfectly secure and all of the bricks to be laid in the best of Rosendale cement.”

The two circa 1900 photos below are courtesy of Lyle Griffin. (Click on photos to enlarge.)

Popular author Edward Rowe Snow wrote in Lighthouses of New England about Keeper Joseph Maddocks's wife, Clara (Emery) Maddocks. Snow interviewed her when she was 102 years old. Maddocks became keeper at Owl's Head in 1873, and there were at least 11 shipwrecks in the vicinity during his 23 years as keeper. Mrs. Maddocks remembered a particularly cold winter when the bay was so frozen that she observed a horse and sleigh cross from Rockland to Vinalhaven.

According to Dave Maddocks, Joseph Maddocks's great grandson, "Joseph G. Maddocks was part of the Maine contingent which turned back Southern soldiers at the critical battle of Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. He was wounded in that battle and it was Clara who nursed him to recovery. Marriage followed. His Civil War discharge was his proudest possession, according to my father."

Mary Bradford Crowninshield's 1886 book, All Among the Lighthouses, described an 1886 visit of a lighthouse inspector to Owl's Head. The inspector and two children viewed the fog bell:

The keeper wound an immense crank, which raised a heavy weight, which in turn operated the machinery; and then they waited for the sound of the bell, the first clanging tone of which nearly deafened them, and drove them from the spot. It struck at intervals of about seven seconds, first one blow, and then two; and they heard its loud, brazen tone ringing on the air after they had mounted these steps, descended the others, and were back on board the steamer.

Above right: This photo was published in 1946 with the following caption: "Standby equipment: Keeper George Woodward of Owl's Head Lighthouse, ME, cleans a kerosene lamp, kept ready for use should electric power fail." U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Augustus B. Hamor, previously keeper for 17 years at Maine's Egg Rock Light, came to Owl's Head as keeper in 1930. Keeper Hamor had a springer spaniel named Spot who gained wide fame among local mariners. Spot learned to pull the rope that rang the fog bell with his teeth, a ritual he repeated for every approaching vessel. The boats would answer with a whistle or bell, and Spot would bark excitedly.

Mary Bradford Crowninshield's 1886 book, All Among the Lighthouses, described an 1886 visit of a lighthouse inspector to Owl's Head. The inspector and two children viewed the fog bell:

The keeper wound an immense crank, which raised a heavy weight, which in turn operated the machinery; and then they waited for the sound of the bell, the first clanging tone of which nearly deafened them, and drove them from the spot. It struck at intervals of about seven seconds, first one blow, and then two; and they heard its loud, brazen tone ringing on the air after they had mounted these steps, descended the others, and were back on board the steamer.

Above right: This photo was published in 1946 with the following caption: "Standby equipment: Keeper George Woodward of Owl's Head Lighthouse, ME, cleans a kerosene lamp, kept ready for use should electric power fail." U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Augustus B. Hamor, previously keeper for 17 years at Maine's Egg Rock Light, came to Owl's Head as keeper in 1930. Keeper Hamor had a springer spaniel named Spot who gained wide fame among local mariners. Spot learned to pull the rope that rang the fog bell with his teeth, a ritual he repeated for every approaching vessel. The boats would answer with a whistle or bell, and Spot would bark excitedly.

Spot's unusual abilities turned out to be good for more than entertainment. One stormy night the Matinicus mail boat almost ran aground at Owl's Head. It was Spot's loud barking that warned the captain just in time and enabled him to steer clear of the rocks.

The much beloved Spot is said to be buried on the side of the hill near the former location of the fog bell, but the location is not marked.

Melvin Davis, Jr., was the Coast Guard officer in charge 1965-68. In an email in February 2011, he shared his memories of Owls Head:

At the time it was a family light station. I considered it choice duty after spending most of my time on sea duty, but like any duty it had its responsibilities that were expected of me . . . especially as officer in charge.

Every Christmas time we would have a visitor from the sky. No, not Santa and his reindeer, but the "Flying Santa Claus," Edward Rowe Snow aboard his fixed winged airplane. It was a real exciting time for the family. I would know approximately what time he was due to arrive, so as to get the family outside for the big event. I would tell them to listen for the airplane. Soon we would hear it coming with its engine roaring. He would circle a couple of times around the lighthouse while we waved frantically at him. Then he would come in real low down by the beach on the west side of the lighthouse and dwelling. He would tilt his wing down and drop Christmas packages to us. The kids would run down the hill to collect all the packages.

One Christmas we had the honor and privilege of meeting Edward Rowe Snow. After dropping packages to us he landed at Owls Head Airport. The Coast Guard drove him over to see us. He was dressed in his Santa suit and even though he dropped the kids presents he brought them an extra gift. He also autographed one of his books.

When I first went to Owls Head Light the fog signal was sirens and that took some getting used to. I believe it was in the summer of 1966; we had 40 days and nights of fog. The fog signal had to run steady. The sirens would break down and I would have to try to fix them. If I couldn't, I had to send out a "notice to mariners" and get a technician as soon as possible. Shortly afterward they replaced the sirens with horns that we hear today.

Sometimes during a bad storm we would lose power (it always seemed to happen at night). I used to think as I opened that old creaking metal door and looked up the dark tower, could it be true that these old lighthouses built back in the 1800s really are haunted by their past keepers? As I ascended the stairs, using only a flashlight to guide my way, each footstep echoed throughout the tower making my surroundings eerie and creepy. The tower was cold damp and musty smelling. I would remind myself that my mind was just playing tricks on me and all I had to do was do my job and fix the light. After the light was lit up again, I could see the interior of the tower and once again the mariners were guided by its light.

We weathered many storms on Owls Head Light, but there is one I remember above them all. I believe it was the winter of 1967-1968. It was a fierce nor'easter. The wind howled and the snow blew to whiteout and it was very cold. Everything was fine, then the lights went out. The alarms sounded and the generator kicked on and took over. After resetting all the alarms things quieted down. It was around 8 or 9 p.m. Then, around 10 p.m. everything seemed fine -- the light was on, the fog signal was on, and the generator was running fine, so I went to bed.

Around 2 a.m. the alarms started going off and everything was in darkness. I jumped out of bed, got dressed, grabbed my flashlight and went out to investigate. By this time the snow was well above my knees. I went to the generator house, opened the door and got a face full of steam. After the steam subsided and I could see with my flashlight, I found that the fan to the engine flew apart and went through the radiator. I knew there was nothing I could do so, I had to get a "notice to mariners" out as soon as I could.

Getting back to the house I found the phone was dead also, so I couldn't call the Rockland Coast Guard to get the notice out. I knew then I had to get to the nearest phone which was approximately three miles away, but I didn't know if their phone worked or not either. I knew I had to try anyway. I told my family the situation and had them all stay in the kitchen area where the kerosene oil burner stove was, which was the only source of heat we had because of no electrical power to run the furnace. I had a four-wheel drive Jeep but knew that it was useless in the deep snow, so I trudged through the blowing deep snow.

I finally got to the house at about 4 a.m. and pounded on the door to wake the people up. They warmly welcomed me in after they realized I was the lighthouse keeper. They gave me a cup of coffee to warm me and gladly allowed me to use their phone to get the "notice to mariners" out. Later I found out that a tree had fallen across the wires leading to the lighthouse. Irving Smith of Owls Head normally plowed out the lighthouse road with his pickup truck, but this time because there was so much snow he had to use his bull dozer. After a few days, power was restored, generator repaired, and Owls Head Lighthouse was back in service for the mariners.

The Lord looked out for us on many, many occasions. I give thanks to Him for it all. I pray you will enjoy a little part of my career in the United States Coast Guard as lighthouse keeper at Owls Head Light. Little did I know at the time that me and my family would be a part of Coast Guard history.

Melvin Davis, Jr., was the Coast Guard officer in charge 1965-68. In an email in February 2011, he shared his memories of Owls Head:

At the time it was a family light station. I considered it choice duty after spending most of my time on sea duty, but like any duty it had its responsibilities that were expected of me . . . especially as officer in charge.

Every Christmas time we would have a visitor from the sky. No, not Santa and his reindeer, but the "Flying Santa Claus," Edward Rowe Snow aboard his fixed winged airplane. It was a real exciting time for the family. I would know approximately what time he was due to arrive, so as to get the family outside for the big event. I would tell them to listen for the airplane. Soon we would hear it coming with its engine roaring. He would circle a couple of times around the lighthouse while we waved frantically at him. Then he would come in real low down by the beach on the west side of the lighthouse and dwelling. He would tilt his wing down and drop Christmas packages to us. The kids would run down the hill to collect all the packages.

One Christmas we had the honor and privilege of meeting Edward Rowe Snow. After dropping packages to us he landed at Owls Head Airport. The Coast Guard drove him over to see us. He was dressed in his Santa suit and even though he dropped the kids presents he brought them an extra gift. He also autographed one of his books.

When I first went to Owls Head Light the fog signal was sirens and that took some getting used to. I believe it was in the summer of 1966; we had 40 days and nights of fog. The fog signal had to run steady. The sirens would break down and I would have to try to fix them. If I couldn't, I had to send out a "notice to mariners" and get a technician as soon as possible. Shortly afterward they replaced the sirens with horns that we hear today.

Sometimes during a bad storm we would lose power (it always seemed to happen at night). I used to think as I opened that old creaking metal door and looked up the dark tower, could it be true that these old lighthouses built back in the 1800s really are haunted by their past keepers? As I ascended the stairs, using only a flashlight to guide my way, each footstep echoed throughout the tower making my surroundings eerie and creepy. The tower was cold damp and musty smelling. I would remind myself that my mind was just playing tricks on me and all I had to do was do my job and fix the light. After the light was lit up again, I could see the interior of the tower and once again the mariners were guided by its light.

We weathered many storms on Owls Head Light, but there is one I remember above them all. I believe it was the winter of 1967-1968. It was a fierce nor'easter. The wind howled and the snow blew to whiteout and it was very cold. Everything was fine, then the lights went out. The alarms sounded and the generator kicked on and took over. After resetting all the alarms things quieted down. It was around 8 or 9 p.m. Then, around 10 p.m. everything seemed fine -- the light was on, the fog signal was on, and the generator was running fine, so I went to bed.

Around 2 a.m. the alarms started going off and everything was in darkness. I jumped out of bed, got dressed, grabbed my flashlight and went out to investigate. By this time the snow was well above my knees. I went to the generator house, opened the door and got a face full of steam. After the steam subsided and I could see with my flashlight, I found that the fan to the engine flew apart and went through the radiator. I knew there was nothing I could do so, I had to get a "notice to mariners" out as soon as I could.

Getting back to the house I found the phone was dead also, so I couldn't call the Rockland Coast Guard to get the notice out. I knew then I had to get to the nearest phone which was approximately three miles away, but I didn't know if their phone worked or not either. I knew I had to try anyway. I told my family the situation and had them all stay in the kitchen area where the kerosene oil burner stove was, which was the only source of heat we had because of no electrical power to run the furnace. I had a four-wheel drive Jeep but knew that it was useless in the deep snow, so I trudged through the blowing deep snow.

I finally got to the house at about 4 a.m. and pounded on the door to wake the people up. They warmly welcomed me in after they realized I was the lighthouse keeper. They gave me a cup of coffee to warm me and gladly allowed me to use their phone to get the "notice to mariners" out. Later I found out that a tree had fallen across the wires leading to the lighthouse. Irving Smith of Owls Head normally plowed out the lighthouse road with his pickup truck, but this time because there was so much snow he had to use his bull dozer. After a few days, power was restored, generator repaired, and Owls Head Lighthouse was back in service for the mariners.

The Lord looked out for us on many, many occasions. I give thanks to Him for it all. I pray you will enjoy a little part of my career in the United States Coast Guard as lighthouse keeper at Owls Head Light. Little did I know at the time that me and my family would be a part of Coast Guard history.

The last civilian keeper was Douglas L. Larrabee, who retired in 1963. Dave Bennett, a Maine native who was the Coast Guard keeper for 30 months ending in December 1972, was profiled in a 1972 newspaper article. Bennett lived at the Owls Head station with his wife, Jane, and their young son, Chriss.

“We fell in love with the place,” said Bennett. “Chriss knows all about bells, buoys, and lights, just like a kid on a ranch knows about horses. He also knows all about the cliffs, and we’ve never had any trouble.”

Right: Webmaster Jeremy D'Entremont and Malcolm Rouse, the last Coast Guard keeper at Owls Head, in 1988.

The bell tower is gone, but an 1895 oil house remains. The wooden ramp and stairway leading to the tower are unique among New England lighthouses.

In October 2006, Coastal Living magazine proclaimed Owls Head Light number one among America’s haunted lighthouses, and there’s no shortage of stories to back up that claim. The lighthouse was also featured in a documentary on haunted lighthouses on the Travel Channel.

Right: Webmaster Jeremy D'Entremont and Malcolm Rouse, the last Coast Guard keeper at Owls Head, in 1988.

The bell tower is gone, but an 1895 oil house remains. The wooden ramp and stairway leading to the tower are unique among New England lighthouses.

In October 2006, Coastal Living magazine proclaimed Owls Head Light number one among America’s haunted lighthouses, and there’s no shortage of stories to back up that claim. The lighthouse was also featured in a documentary on haunted lighthouses on the Travel Channel.

Andy Germann was the Coast Guard keeper for a few years in the mid-1980s. His wife, Denise, later told the Bangor Daily News about a particular night when her husband went outside to secure some construction materials; the tower and house were undergoing some renovations at the time. Denise rolled over and then felt her husband get back into bed, or so she thought.

“How’d you make out outside?” she asked, but there was no reply. When she turned over, she saw the “indentation of a body” next to her. The indentation was moving, as if an invisible person was shifting in the bed. “I’m a pretty practical person,” she says. “I don’t drink. I don’t do drugs. I’m positive it wasn’t a dream.” After a few minutes, she asked the “visitor” to go away so she could get some sleep.

The next morning, Andy Germann told his wife that when he had gotten out of bed the night before to go outside, he saw a “cloud of smoke hovering over the floor.” The cloud, he said, went right through him and into the bedroom. Just after that, Denise had her encounter with the “indentation.”

Left: Gerard Graham was the Coast Guard officer in charge 1987-88. With him in the lantern room in this photo are his wife Debbie and their youngest daughter Claire. Courtesy of Debbie Graham.

Debbie Graham, who lived at the station in 1987-88 with her husband, Coast Guard keeper Gerard Graham and their young daughter, Claire, says that the Germanns warned her and her husband about the resident ghost when they moved in. The Grahams didn’t take the warning seriously, and they chose an upstairs room that the Germanns had said was particularly “active” to be Claire’s bedroom.

For the entire time that the Grahams lived at the lighthouse, Claire had an imaginary friend she later described as looking like an “old sea captain.” Once, in the middle of the night, Claire came into her parents’ room excitedly telling them, “Fog’s rolling in! Time to put the foghorn on!” Nobody had ever spoken of such things in front of her, and the Grahams were mystified by Claire’s use of such jargon.

Another common occurrence was the appearance of footprints in the snow, seemingly beginning from nowhere and leading up the wooden stairs that lead to the lighthouse tower. According to the historian William O. Thomson, on some occasions the keepers would find the door to the tower open, with the lens and brass inside freshly polished.

Malcolm Rouse, formerly at West Quoddy Head Light, was the last Coast Guard keeper at Owl's Head before its 1989 automation. He later said that his wife insisted that the outline of a person dressed in white could be seen in one of the windows, and their son often woke up insisting that he saw a woman sitting in a chair in his room.

In December 2007, the lighthouse tower was licensed to the American Lighthouse Foundation. Then, in late 2012, it was announced that the keeper's house had also been licensed to the American Lighthouse Foundation and that it would serve as the organization's headquarters.

The next morning, Andy Germann told his wife that when he had gotten out of bed the night before to go outside, he saw a “cloud of smoke hovering over the floor.” The cloud, he said, went right through him and into the bedroom. Just after that, Denise had her encounter with the “indentation.”

Left: Gerard Graham was the Coast Guard officer in charge 1987-88. With him in the lantern room in this photo are his wife Debbie and their youngest daughter Claire. Courtesy of Debbie Graham.

Debbie Graham, who lived at the station in 1987-88 with her husband, Coast Guard keeper Gerard Graham and their young daughter, Claire, says that the Germanns warned her and her husband about the resident ghost when they moved in. The Grahams didn’t take the warning seriously, and they chose an upstairs room that the Germanns had said was particularly “active” to be Claire’s bedroom.

For the entire time that the Grahams lived at the lighthouse, Claire had an imaginary friend she later described as looking like an “old sea captain.” Once, in the middle of the night, Claire came into her parents’ room excitedly telling them, “Fog’s rolling in! Time to put the foghorn on!” Nobody had ever spoken of such things in front of her, and the Grahams were mystified by Claire’s use of such jargon.

Another common occurrence was the appearance of footprints in the snow, seemingly beginning from nowhere and leading up the wooden stairs that lead to the lighthouse tower. According to the historian William O. Thomson, on some occasions the keepers would find the door to the tower open, with the lens and brass inside freshly polished.

Malcolm Rouse, formerly at West Quoddy Head Light, was the last Coast Guard keeper at Owl's Head before its 1989 automation. He later said that his wife insisted that the outline of a person dressed in white could be seen in one of the windows, and their son often woke up insisting that he saw a woman sitting in a chair in his room.

In December 2007, the lighthouse tower was licensed to the American Lighthouse Foundation. Then, in late 2012, it was announced that the keeper's house had also been licensed to the American Lighthouse Foundation and that it would serve as the organization's headquarters.

One of the most beautiful lighthouses in Maine from land or water, Owl's Head Light is a must-visit for the lighthouse fan.

The oil house

The grounds are open daily; there is a large parking area and a moderate walk to the lighthouse. The interpretation center and gift shop in the keeper's house are open seasonally, and the tower is sometimes open for climbing.

The lighthouse can also be seen from the Rockland - Vinalhaven ferry and from various excursion boats out of Rockland, Rockport and Camden.

The lighthouse can also be seen from the Rockland - Vinalhaven ferry and from various excursion boats out of Rockland, Rockport and Camden.

Listen to the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast "Light Hearted," episode 156: Bob, Ann, and Dominic Trapani discuss Owls Head Light Station:

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Isaac Stearns (Sterns) (1825-1838); William Masters (1838-1841 and 1845-1849); Penly Haines (1841-1845); Henry Achorn (1849-1853); Joshua Adams (1853-1857); Asa Coombs (1857-1861); G. D. Worcester (Woolsley) (1861-1873); Joseph Maddocks (1873-1896); G. H. Maddocks (1896-1904?); Llewellyn Samuel Norwood (1904-1911); Paul Sawyer (1911); Charles Sawyer (1911?); Charles Franklin Chester (1911-1920); Allen Carter Holt (1920-1928); Albion Faulkingham (c. 1928-1930); Augustus B. Hamor (1930-1945); George Woodward (1945-1947); Archford (Archie) Haskins (1947-1953); Douglas L. Larabee (Coast Guard, 1953-1963); Dan Elliott (Coast Guard relief keeper, 1954); Leon Detz (Coast Guard, 1963-1970); Ed Dodge (Coast Guard relief keeper c. 1962-1964); Melvin Davis, Jr. (Coast Guard, 1965-1968; Larry Rowe (Coast Guard, c. 1968-?); David Bennett (Coast Guard, 1970-1972); James Sullivan (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); Gorham Rowell (Coast Guard, 1974-1976); Joseph A. Gourde Jr. (Coast Guard, 1976-1978); Raymond Slade (Coast Guard, 1978-1981); John Norton (Coast Guard, c. 1981-1983); Andy Germann (Coast Guard, 1983-1987); Gerard J. Graham (Coast Guard, 1987-1988); Malcolm Rouse (Coast Guard, 1988-1989).

Isaac Stearns (Sterns) (1825-1838); William Masters (1838-1841 and 1845-1849); Penly Haines (1841-1845); Henry Achorn (1849-1853); Joshua Adams (1853-1857); Asa Coombs (1857-1861); G. D. Worcester (Woolsley) (1861-1873); Joseph Maddocks (1873-1896); G. H. Maddocks (1896-1904?); Llewellyn Samuel Norwood (1904-1911); Paul Sawyer (1911); Charles Sawyer (1911?); Charles Franklin Chester (1911-1920); Allen Carter Holt (1920-1928); Albion Faulkingham (c. 1928-1930); Augustus B. Hamor (1930-1945); George Woodward (1945-1947); Archford (Archie) Haskins (1947-1953); Douglas L. Larabee (Coast Guard, 1953-1963); Dan Elliott (Coast Guard relief keeper, 1954); Leon Detz (Coast Guard, 1963-1970); Ed Dodge (Coast Guard relief keeper c. 1962-1964); Melvin Davis, Jr. (Coast Guard, 1965-1968; Larry Rowe (Coast Guard, c. 1968-?); David Bennett (Coast Guard, 1970-1972); James Sullivan (Coast Guard, 1972-1974); Gorham Rowell (Coast Guard, 1974-1976); Joseph A. Gourde Jr. (Coast Guard, 1976-1978); Raymond Slade (Coast Guard, 1978-1981); John Norton (Coast Guard, c. 1981-1983); Andy Germann (Coast Guard, 1983-1987); Gerard J. Graham (Coast Guard, 1987-1988); Malcolm Rouse (Coast Guard, 1988-1989).