History of Minots Ledge Light, Scituate, Massachusetts

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Minot's Rocks... lie off the southeastern chop of Boston Bay. These rocks or ledges... have been the terror of mariners for a long period of years; they have been, probably, the cause of a greater number of wrecks than any other ledges or reefs upon the coast. -- Captain William H. Swift

It’s not the tallest or the oldest lighthouse in Massachusetts, and few would claim it’s the prettiest. But this rugged, waveswept tower has probably sparked more imaginations—and possibly more romances—than any beacon in the state.

Minots Ledge—about a mile offshore, near the line between the South Shore towns of Cohasset and Scituate—is part of the dangerous Cohasset Rocks, formerly known as the Conyhasset or Quonahassit after a local Indian tribe. It’s said that the Quonahassit people would visit the ledges to leave gifts of arrowheads, beads, and various trinkets, in an effort to appease the spirit they believed resided in the rocks. If the spirit became angry, they thought, it would bring destructive storms to the tribe.

Minots Ledge itself was named for George Minot, a prominent Bostonian who owned the city's T Wharf in the mid-1700s. A ship belonging to Minot was wrecked at the ledge, hence the name.

Minots Ledge—about a mile offshore, near the line between the South Shore towns of Cohasset and Scituate—is part of the dangerous Cohasset Rocks, formerly known as the Conyhasset or Quonahassit after a local Indian tribe. It’s said that the Quonahassit people would visit the ledges to leave gifts of arrowheads, beads, and various trinkets, in an effort to appease the spirit they believed resided in the rocks. If the spirit became angry, they thought, it would bring destructive storms to the tribe.

Minots Ledge itself was named for George Minot, a prominent Bostonian who owned the city's T Wharf in the mid-1700s. A ship belonging to Minot was wrecked at the ledge, hence the name.

The roll call of shipwrecks through the years near the Cohasset Rocks—especially Minots Ledge—was lengthy, with many lives lost. In August 1838, the Boston Marine Society appointed a committee of three to study the feasibility of a lighthouse on the ledge.

The first lighthouse at Minots Ledge

The committee reported in November 1838:

The practibility of building a Light house on it that will withstand the force of the sea does not admit of a doubt—the importance of having a light house on a rock so dangerous to the navigation of Boston, on which so many lives, & so much property has been lost is too well known to need comment. . .

The Marine Society repeatedly petitioned Congress for a lighthouse between 1839 and 1841, with no positive results. The civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis made reference to the problem in his 1843 report to Congress:

For a long series of years, petitions have been presented to Congress, from the citizens of Boston, for erecting a light-house on these dreadful rocks, but no action has ever yet been taken upon the subject. One of the causes of frequent shipwrecks on these rocks has been the light-house at Scituate, four miles to the leeward of the reef, which has been repeatedly mistaken for Boston light, and thus caused the death of many a brave seaman and the loss of large amounts of property. Not a winter passes without one or more of these fearful accidents occurring. . . . One of the most interesting objects of this inspection was to ascertain the feasibility of erecting a light-house on the extremity of the Cohasset reef; and it was found that, though formidable difficulties would embarrass the undertaking, still they were not greater than such as were successfully triumphed over by a “Smeaton” or a “Stevenson.”

Lewis was referring to John Smeaton, builder of the 1759 lighthouse on the treacherous Eddystone Rocks off Cornwall, England, and to Robert Stevenson, who was largely responsible for the construction of Bell Rock Lighthouse (1811) off the east coast of Scotland. The towers at Eddystone and Bell Rock—both constructed of interlocking granite blocks—were among the earliest and sturdiest wave-swept lighthouses in the world.

The practibility of building a Light house on it that will withstand the force of the sea does not admit of a doubt—the importance of having a light house on a rock so dangerous to the navigation of Boston, on which so many lives, & so much property has been lost is too well known to need comment. . .

The Marine Society repeatedly petitioned Congress for a lighthouse between 1839 and 1841, with no positive results. The civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis made reference to the problem in his 1843 report to Congress:

For a long series of years, petitions have been presented to Congress, from the citizens of Boston, for erecting a light-house on these dreadful rocks, but no action has ever yet been taken upon the subject. One of the causes of frequent shipwrecks on these rocks has been the light-house at Scituate, four miles to the leeward of the reef, which has been repeatedly mistaken for Boston light, and thus caused the death of many a brave seaman and the loss of large amounts of property. Not a winter passes without one or more of these fearful accidents occurring. . . . One of the most interesting objects of this inspection was to ascertain the feasibility of erecting a light-house on the extremity of the Cohasset reef; and it was found that, though formidable difficulties would embarrass the undertaking, still they were not greater than such as were successfully triumphed over by a “Smeaton” or a “Stevenson.”

Lewis was referring to John Smeaton, builder of the 1759 lighthouse on the treacherous Eddystone Rocks off Cornwall, England, and to Robert Stevenson, who was largely responsible for the construction of Bell Rock Lighthouse (1811) off the east coast of Scotland. The towers at Eddystone and Bell Rock—both constructed of interlocking granite blocks—were among the earliest and sturdiest wave-swept lighthouses in the world.

Lewis's report listed more than 40 vessels that had been lost in the vicinity from 1832 to 1841. He asserted, "A light house on this reef is more required than on any part of the seaboard of New England."

In March 1847, Congress finally appropriated $20,000 for a lighthouse on the ledge; an additional $19,500 would eventually be needed for the completion of the project, including $4,500 for the lighting apparatus. The site selected was the rock known as the Outer Minot. Some believed a granite tower similar to England's famed Eddystone Light would be the proper solution, but Captain William H. Swift of the Topographical Department, chosen to plan the tower, believed it impossible to build such a tower on the mostly submerged ledge.

The ledge remained unmarked, and vessels continued to have trouble negotiating the area. On February 12, 1847, a brig from New Orleans struck the rocks in the vicinity of Minot’s Ledge. Luckily, the ship was able to make it to Boston with nine feet of water in its hold.

Less than a month later, Congress finally appropriated $20,000 for a lighthouse on the ledge; an additional $19,500 would eventually be needed for the completion of the project, including $4,500 for the lighting apparatus. The site selected was the rock known as the Outer Minot.

Many people believed a granite tower similar to the waveswept lighthouses of the British Isles to be the proper solution, as Parris had suggested, but Captain Swift deemed it impractical to build such a tower on the small (about 25 feet wide), mostly submerged ledge.

The ledge remained unmarked, and vessels continued to have trouble negotiating the area. On February 12, 1847, a brig from New Orleans struck the rocks in the vicinity of Minot’s Ledge. Luckily, the ship was able to make it to Boston with nine feet of water in its hold.

Less than a month later, Congress finally appropriated $20,000 for a lighthouse on the ledge; an additional $19,500 would eventually be needed for the completion of the project, including $4,500 for the lighting apparatus. The site selected was the rock known as the Outer Minot.

Many people believed a granite tower similar to the waveswept lighthouses of the British Isles to be the proper solution, as Parris had suggested, but Captain Swift deemed it impractical to build such a tower on the small (about 25 feet wide), mostly submerged ledge.

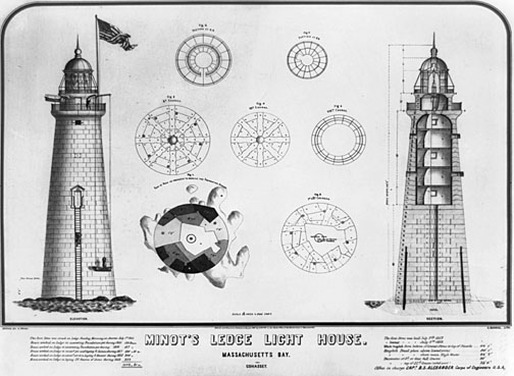

Instead, Swift planned an iron pile lighthouse, a 70-foot-tall, spidery structure on piles drilled into the rock, on the theory that waves would pass harmlessly through the structure. The cost-conscious lighthouse administrators of the day appreciated the fact that a tower of this type would be far less expensive than one made of stone.

Work began in the summer of 1847. A schooner transported workers and materials to the site, and the workers slept on the vessel each night. A drill, which required four men to operate, was supported on a wooden platform. The contractor on the project was Benjamin Pomeroy.

James Sullivan Savage, who had built Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument, oversaw the drilling operations. The drilling equipment was twice swept off the ledge in 1847, and it took nearly two full seasons to complete the drilling.

A few weeks after work ceased for the season in late October 1847, the ship Alabama struck the ledge and sank about two miles to the east. The crew escaped safely, but the ship and its cargo were a total loss. Much of the cargo was later salvaged, and crockery from the Alabama found its way into many Cohasset homes.

The octagonal keepers' quarters (14 feet in diameter) and wrought-iron lantern were built atop nine 10-inch-diameter piles, cemented into 5-foot-deep holes drilled in the ledge and braced horizontally by three sets of iron rods.

James Sullivan Savage, who had built Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument, oversaw the drilling operations. The drilling equipment was twice swept off the ledge in 1847, and it took nearly two full seasons to complete the drilling.

A few weeks after work ceased for the season in late October 1847, the ship Alabama struck the ledge and sank about two miles to the east. The crew escaped safely, but the ship and its cargo were a total loss. Much of the cargo was later salvaged, and crockery from the Alabama found its way into many Cohasset homes.

The octagonal keepers' quarters (14 feet in diameter) and wrought-iron lantern were built atop nine 10-inch-diameter piles, cemented into 5-foot-deep holes drilled in the ledge and braced horizontally by three sets of iron rods.

In his book Cape Cod, Henry David Thoreau described passing Minot's Ledge Light in 1849:

Here was the new iron light-house, then unfinished, in the shape of an egg-shell painted red, and placed high on iron pillars, like the ovum of a sea monster floating on the waves...

When I passed it the next summer it was finished and two men lived in it, and a light-house keeper said that ina recent gale it had rocked so as to shake the plates off the table. Think of making your bed thus in the crest of a breaker!

Henry David Thoreau

The lighthouse was finished in late 1849. It was lighted for the first time on January 1, 1850. It was the first lighthouse in the United States to be exposed to the ocean's full fury.

The first keeper—at $600 yearly—was Isaac Dunham, a Massachusetts native. There were usually two keepers on duty at a time; Dunham’s assistants included his son, Isaac A. Dunham, and Russell Higgins of Cape Cod.

Dunham didn’t believe the structure was safe. Only a week after the light went into service, he wrote in the log (original spelling retained):

Clensd the Lantern for Liting in a tremendous Gale of wind. It seames as though the Light House would go from the Rock.

The first keeper—at $600 yearly—was Isaac Dunham, a Massachusetts native. There were usually two keepers on duty at a time; Dunham’s assistants included his son, Isaac A. Dunham, and Russell Higgins of Cape Cod.

Dunham didn’t believe the structure was safe. Only a week after the light went into service, he wrote in the log (original spelling retained):

Clensd the Lantern for Liting in a tremendous Gale of wind. It seames as though the Light House would go from the Rock.

In April 1850, Dunham wrote:

April 5—This day and the last night will long be remembered by me as one of the most trying that I have ever experience during my life.

April 6—The wind E. blowing very hard with an ugly sea which makes the light real [sic] like a Drunken Man — I hope God will in mercy still the raging sea — or we must perish. . . . God only knows what the end will be.

At 4 P.M. the gale continues with great fury. It appears to me that if the wind continues from the East and it now is that we cannot survive the night—if it is to be so—O God receive my unworthy soul for Christ sake for in him I put my trust.

Isaac Dunham

Fearing for his life, Dunham requested that the tower be strengthened, but Captain Swift assured everyone that it was perfectly safe. Unconvinced, Dunham resigned after 10 months as keeper. His two assistants also resigned.

The second keeper was John W. Bennett, a veteran of 25 years at sea and a former first lieutenant in the British Navy who was described by the local lighthouse superintendent as “a man of courage as well as character.” Bennett was confident at first, but he soon came to believe the lighthouse was unsafe. After a storm in the late fall, Bennett contacted the local superintendent, Philip Greely, who sent a committee to examine the structure. Visiting on a calm day, the committee concluded that the tower would withstand “any storm without danger.” The keepers were unconvinced.

Bennett installed a thick rope hawser extending from the tower to a rock about 200 feet away. A basket or sling was suspended from the rope, with the idea that the keepers could use it as an escape route in emergencies. Bennett apparently did leave the lighthouse via the hawser in times of heavy seas.

A 640-pound fog bell was installed in late October 1850, to be sounded in times of “fog and snow storms, or other thick weather.”

The second keeper was John W. Bennett, a veteran of 25 years at sea and a former first lieutenant in the British Navy who was described by the local lighthouse superintendent as “a man of courage as well as character.” Bennett was confident at first, but he soon came to believe the lighthouse was unsafe. After a storm in the late fall, Bennett contacted the local superintendent, Philip Greely, who sent a committee to examine the structure. Visiting on a calm day, the committee concluded that the tower would withstand “any storm without danger.” The keepers were unconvinced.

Bennett installed a thick rope hawser extending from the tower to a rock about 200 feet away. A basket or sling was suspended from the rope, with the idea that the keepers could use it as an escape route in emergencies. Bennett apparently did leave the lighthouse via the hawser in times of heavy seas.

A 640-pound fog bell was installed in late October 1850, to be sounded in times of “fog and snow storms, or other thick weather.”

Bennett and his assistants increasingly lived in fear of their lives as stormy weather became more frequent with the onset of winter.

Assistant Keeper Samuel Gardiner described a December storm in a letter to Bennett, who was away:

The house was shaking very bad from 9 am until 4 pm. The watch bell was constantly ringing and it was almost impossible for us to stand on our feet. There was a barrel of water standing in the cellar which was half emptied by the shaking of the house. . . . The piles beneath us are now one solid mass of ice nearly as big as a three barrel cask. As for the ladder, that cannot be found. . . . I assure you sir that it was the most awful situation that ever I was placed in before in my life . . .

During a desperate night, Bennett wrote the following message:

These last forty-eight hours have been the most terrific that I have witnessed for many a year. . . . The raging violence of the sea no man can appreciate, unless he is an eye witness. . . .

The rods put into the lower section are bent up in fantastic shapes; some are torn asunder from their fastenings; the ice is so massive that there is no appearance of the ladder; the sea is now running at least twenty-five feet above the level, and each one roars like a heavy peal of thunder; the northern part of the foundation is split, and the light house shakes at least two feet each way. I feel as seasick as ever I did on board a ship.

Our lantern windows are all iced up outside, although we have a fire continually burning; and it is not without imminent peril that we can climb up outside to scrape it off, which I have done several times already. I have a dread of some ship striking against us, although we have kept the bell constantly ringing all night. Our water is a solid mass of ice in the casks, which we have been obliged to cut to pieces with an axe before we could obtain any drink.

Our situation is perilous. If anything happens before day dawns on us again, we have no hope of escape. But I shall, if it be God’s will, die in the performance of my duty.

P.S. I have put a copy of this in a bottle, with the hope it may be picked up in case of any accident to us.

The house was shaking very bad from 9 am until 4 pm. The watch bell was constantly ringing and it was almost impossible for us to stand on our feet. There was a barrel of water standing in the cellar which was half emptied by the shaking of the house. . . . The piles beneath us are now one solid mass of ice nearly as big as a three barrel cask. As for the ladder, that cannot be found. . . . I assure you sir that it was the most awful situation that ever I was placed in before in my life . . .

During a desperate night, Bennett wrote the following message:

These last forty-eight hours have been the most terrific that I have witnessed for many a year. . . . The raging violence of the sea no man can appreciate, unless he is an eye witness. . . .

The rods put into the lower section are bent up in fantastic shapes; some are torn asunder from their fastenings; the ice is so massive that there is no appearance of the ladder; the sea is now running at least twenty-five feet above the level, and each one roars like a heavy peal of thunder; the northern part of the foundation is split, and the light house shakes at least two feet each way. I feel as seasick as ever I did on board a ship.

Our lantern windows are all iced up outside, although we have a fire continually burning; and it is not without imminent peril that we can climb up outside to scrape it off, which I have done several times already. I have a dread of some ship striking against us, although we have kept the bell constantly ringing all night. Our water is a solid mass of ice in the casks, which we have been obliged to cut to pieces with an axe before we could obtain any drink.

Our situation is perilous. If anything happens before day dawns on us again, we have no hope of escape. But I shall, if it be God’s will, die in the performance of my duty.

P.S. I have put a copy of this in a bottle, with the hope it may be picked up in case of any accident to us.

Captain Swift, who had designed the tower, felt compelled to answer his critics. On January 18, 1851, a letter from Swift was published in the Boston Daily Advertiser. Swift wrote:

Time, the great expounder of the truth or the fallacy of the question, will decide for or against the Minot; but inasmuch as the light has outlived nearly three winters, there is some reason to hope that it may survive one or two more.

Swift expressed some worry about the escape hawser installed by Bennett, calling it a “gross violation of common sense. . . . It needs no Solomon to perceive that the effect of the sea upon this guy is precisely that which a gang of men would exert if laboring at the rope to pull the light-house down.”

During a visit to Boston just after the March storm, assistant keeper Joseph Wilson, a 20-year-old native of England, told a friend that he would stay at the lighthouse as long as Bennett remained in charge. Wilson also said that in the event of a catastrophe, he would stay in the tower as long as it stood. He was confident of his ability to reach shore if the tower should fall.

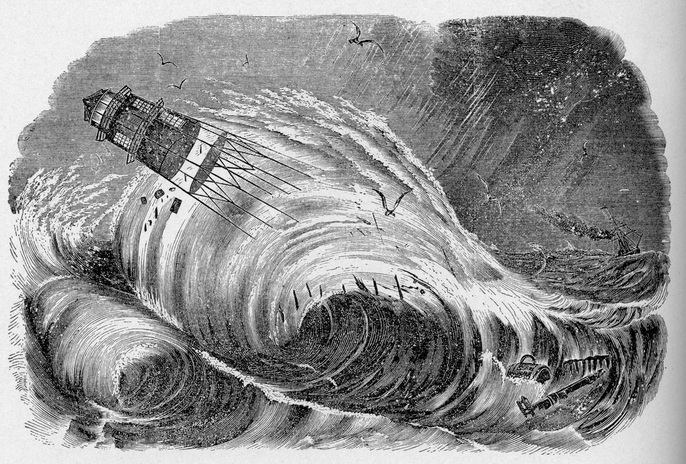

On April 16–17, 1851, a colossal storm brought high seas to the area, turning Boston into an island, washing a schoolhouse and a seawall off Deer Island in Boston Harbor, washing sweeping away several houses in Cohasset, and flooding much of the area. This gale would be immortalized as the Minot’s Light Storm.

Bennett had gone to Boston to see about procuring a new boat (to replace one that was lost in a storm on April 9) on Monday, April 14, and was unable to return to the lighthouse on Tuesday because of heavy seas. The two young assistant keepers, Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine, a 25-year-old native of Portugal, were on duty.

The light was seen to burn through the night on Tuesday, and the tower was last seen from shore, clearly standing, about 4:00 p.m. on Wednesday. Scituate residents reported that the light was last seen burning about 10:00 p.m. on Wednesday night. At some point, as the seas grew more turbulent, Antoine and Wilson dropped a note in a bottle into the waves below. The note, found the following day by a Gloucester fisherman, read:

The lighthouse won’t stand over to night. She shakes 2 feet each way now. -- J.W. + J.A

The tide reached its height around midnight. At about 1:00 a.m., residents on shore heard the frantic ringing of the fog bell at the lighthouse, possibly being sounded as an alarm or call for help.

The central support apparently broke first; a man on shore reported that the tower had a decided list by Wednesday afternoon. The outer supports all snapped by the early hours of Thursday morning.

Evidence suggested the two men left using the escape hawser before the lighthouse fell.

During a visit to Boston just after the March storm, assistant keeper Joseph Wilson, a 20-year-old native of England, told a friend that he would stay at the lighthouse as long as Bennett remained in charge. Wilson also said that in the event of a catastrophe, he would stay in the tower as long as it stood. He was confident of his ability to reach shore if the tower should fall.

On April 16–17, 1851, a colossal storm brought high seas to the area, turning Boston into an island, washing a schoolhouse and a seawall off Deer Island in Boston Harbor, washing sweeping away several houses in Cohasset, and flooding much of the area. This gale would be immortalized as the Minot’s Light Storm.

Bennett had gone to Boston to see about procuring a new boat (to replace one that was lost in a storm on April 9) on Monday, April 14, and was unable to return to the lighthouse on Tuesday because of heavy seas. The two young assistant keepers, Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine, a 25-year-old native of Portugal, were on duty.

The light was seen to burn through the night on Tuesday, and the tower was last seen from shore, clearly standing, about 4:00 p.m. on Wednesday. Scituate residents reported that the light was last seen burning about 10:00 p.m. on Wednesday night. At some point, as the seas grew more turbulent, Antoine and Wilson dropped a note in a bottle into the waves below. The note, found the following day by a Gloucester fisherman, read:

The lighthouse won’t stand over to night. She shakes 2 feet each way now. -- J.W. + J.A

The tide reached its height around midnight. At about 1:00 a.m., residents on shore heard the frantic ringing of the fog bell at the lighthouse, possibly being sounded as an alarm or call for help.

The central support apparently broke first; a man on shore reported that the tower had a decided list by Wednesday afternoon. The outer supports all snapped by the early hours of Thursday morning.

Evidence suggested the two men left using the escape hawser before the lighthouse fell.

Bennett went to the shore about 5:00 a.m. He saw fragments of the lighthouse lantern washing ashore, along with bedding and some of his own clothing. He also found an India rubber life jacket, which looked as if it had been worn by one of the assistant keepers, but was apparently torn from his body by the force of the seas. Two miles of beach were eventually littered with furniture and fragments of the wooden parts of the lighthouse.

The body of Joseph Antoine was soon found at Nantasket Beach in Hull. The remains of Joseph Wilson were found in the following October by Bennett on a small island called Gull Rock, about a mile southwest of Minots Ledge. His position on the island indicated that he may have reached there it alive but died of exposure before morning. Wilson’s skull was fractured, suggesting the possibility that he had fallen or had been struck by wreckage from the lighthouse.

An article in New England Magazine stated:

The keeper's house and lantern were fairly above the reach of the average storm seas; but this was not the case with a lower platform which the over-confident keeper had built upon the second series of rods and tie braces, nor with that fatal 5 1/2-inch hawser which he led from the lantern deck out to an anchorage fifty fathoms inshore... there are engineers who still maintain that a similar structure upon a larger scale, if built upon these rocks, would defy the storms of years.

Others also expressed the belief that a platform the keeper had built provided an additional surface for the waves to lift against, and that the 300 feet of cable extending from the deck, covered with ice, contributed to the tower's demise.

From 1851 to 1860 a lightship replaced the tower at Minots Ledge. Work on the new stone tower began in 1855. The new Minots Light was designed by General Joseph G. Totten of the Lighthouse Board, and it has been called the greatest achievement in American lighthouse engineering.

An article in New England Magazine stated:

The keeper's house and lantern were fairly above the reach of the average storm seas; but this was not the case with a lower platform which the over-confident keeper had built upon the second series of rods and tie braces, nor with that fatal 5 1/2-inch hawser which he led from the lantern deck out to an anchorage fifty fathoms inshore... there are engineers who still maintain that a similar structure upon a larger scale, if built upon these rocks, would defy the storms of years.

Others also expressed the belief that a platform the keeper had built provided an additional surface for the waves to lift against, and that the 300 feet of cable extending from the deck, covered with ice, contributed to the tower's demise.

From 1851 to 1860 a lightship replaced the tower at Minots Ledge. Work on the new stone tower began in 1855. The new Minots Light was designed by General Joseph G. Totten of the Lighthouse Board, and it has been called the greatest achievement in American lighthouse engineering.

Capt. Barton S. Alexander made some modifications in the design and was superintendent of the project. Because the construction could only take place at low tide on calm days, the cutting and assembling of the granite took place at Cohasset's Government Island, attached to the mainland. A team of oxen moved the blocks to a vessel that brought them to the ledge.

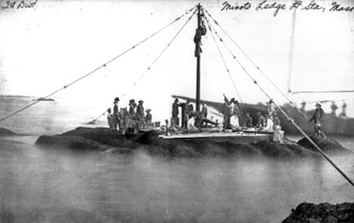

Workers complete the first course of granite at Minot's Ledge

The project had a setback in January 1857, when the iron framework that had been erected was destroyed during a storm. Captain Alexander was discouraged, saying, "If wrought iron won't stand it, I have my fears about a stone tower." He was relieved when it became apparent that the damage was caused by a ship that hit the ledge, not by the waves.

The rocks themselves were damaged by the collision, and the work had to start all over again. On July 9, 1857, the first granite block was laid for the tower.

Many times during the construction waves swept the workers off the rocks. A Cohasset diver, Captain Michael Neptune Brennock, was hired to serve as a lifeguard.

The rocks themselves were damaged by the collision, and the work had to start all over again. On July 9, 1857, the first granite block was laid for the tower.

Many times during the construction waves swept the workers off the rocks. A Cohasset diver, Captain Michael Neptune Brennock, was hired to serve as a lifeguard.

When a wave hit, the men learned to hold on tightly to a steel bolt or rope until the danger passed. Only workers who could swim were allowed to work on the project.

On October 2, 1858, the cornerstone was laid and an official dedication was held at Government Island. Mayor Frederick W. Lincoln of Boston introduced Captain Alexander. In his address Alexander said:

So may it stand, that 'they who go down to the sea in ships' may see this signal fire burning brightly to warn them from the countless rocks that echo with the rage that oft swells from the bosom of old ocean.

The great orator Edward Everett followed Alexander followed:

Well do I remember that dreadful night, when a furious storm swept along the coast of New England... In the course of that tremendous night, the lighthouse on Minot's Ledge disappeared... and with it the two brave men who, in that awful hour, stood bravely at their posts. We have come now, sir, to repair the desolation of that hour.

You can read all of Everett's speech here.

So may it stand, that 'they who go down to the sea in ships' may see this signal fire burning brightly to warn them from the countless rocks that echo with the rage that oft swells from the bosom of old ocean.

The great orator Edward Everett followed Alexander followed:

Well do I remember that dreadful night, when a furious storm swept along the coast of New England... In the course of that tremendous night, the lighthouse on Minot's Ledge disappeared... and with it the two brave men who, in that awful hour, stood bravely at their posts. We have come now, sir, to repair the desolation of that hour.

You can read all of Everett's speech here.

The last stone was laid at Minots Ledge on June 29, 1860, five years minus one day after Alexander and his workmen first landed at the ledge. The final cost of about $300,000 made it one of the most expensive lighthouses in United States history.

The lantern and second-order Fresnel lens were put into place, and the lighthouse was illuminated on November 15, 1860.

The lightship that had served in the interim was described by the Boston Post as being like "farthing candles" compared to the brilliance of the new light.

Built of 1,079 blocks (3,514 tons) of Quincy granite dovetailed together and reinforced with iron shafts, the tower has lasted through countless storms and hurricanes, a testament to its designer and builders. The first 40 feet is solid granite, topped by a storeroom, living quarters, and work space.

Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited Minot's Light in 1871. He wrote:

We find ourselves at the base of the lighthouse rising sheer out of the sea... We are hoisted up forty feet in a chair, some of us; others go up by an iron ladder... The lighthouse rises out of the sea like a beautiful stone cannon, mouth upward, belching forth only friendly fires.

The lightship that had served in the interim was described by the Boston Post as being like "farthing candles" compared to the brilliance of the new light.

Built of 1,079 blocks (3,514 tons) of Quincy granite dovetailed together and reinforced with iron shafts, the tower has lasted through countless storms and hurricanes, a testament to its designer and builders. The first 40 feet is solid granite, topped by a storeroom, living quarters, and work space.

Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited Minot's Light in 1871. He wrote:

We find ourselves at the base of the lighthouse rising sheer out of the sea... We are hoisted up forty feet in a chair, some of us; others go up by an iron ladder... The lighthouse rises out of the sea like a beautiful stone cannon, mouth upward, belching forth only friendly fires.

Despite its solid construction, Minots Light was a difficult assignment for a keeper. The keepers lived part of the time with their families on shore in two duplex houses at Government Island in Cohasset, but they lived most of the time inside the tower.

Levi Creed was at Minots Ledge from 1865 to 1881, first as an assistant and then as principal keeper beginning in 1874. Parmalee McFadden, Creed's nephew, visited the lighthouse when he was 14. Years later, he wrote about the visit in St. Nicholas magazine:

If the sea is very calm, the more venturesome will approach the base and mount the ladder, which reaches some forty feet up to the first opening. If the sea is too rough for this, or when ladies desire to make a visit, the boat is made fast to the lighthouse's buoy, and the visitor is securely tied in a wooden armchair and hauled up by a block and tackle.

This precaution of fastening the visitor in the chair is especially imperative with timid persons or those who are at all liable to become dizzy; for although the chair is hung so as to give it a tilt backward, yet if a person fainted and fell forward, nothing but a strong rope would keep him from falling out of the chair. The rope is tied across from one arm of the chair to the other, very much in the manner in which a baby is made secure in its baby-carriage or go-cart. In winter, when one of the staff of keepers, who has been off duty on shore, comes out to the Light to relieve one of the other two keepers, it is usually so rough and the ladder so incrusted with ice that no other way of gaining admittance is possible except by being hauled up.

If the sea is very calm, the more venturesome will approach the base and mount the ladder, which reaches some forty feet up to the first opening. If the sea is too rough for this, or when ladies desire to make a visit, the boat is made fast to the lighthouse's buoy, and the visitor is securely tied in a wooden armchair and hauled up by a block and tackle.

This precaution of fastening the visitor in the chair is especially imperative with timid persons or those who are at all liable to become dizzy; for although the chair is hung so as to give it a tilt backward, yet if a person fainted and fell forward, nothing but a strong rope would keep him from falling out of the chair. The rope is tied across from one arm of the chair to the other, very much in the manner in which a baby is made secure in its baby-carriage or go-cart. In winter, when one of the staff of keepers, who has been off duty on shore, comes out to the Light to relieve one of the other two keepers, it is usually so rough and the ladder so incrusted with ice that no other way of gaining admittance is possible except by being hauled up.

McFadden described the interior of the tower:

On reaching the first opening in the side, we came into the store-room, filled with fishing-tackle, ropes, harpoons, etc. In the center of this room was a covered well that contained drinking water, and extended down the very core of the otherwise solid granite structure nearly to the level of the sea. Above this room was the kitchen, and above that the sleeping-rooms, and the watch-room, where the keeper sat at night and constantly watched, on the plate-glass of the outer lantern, the reflection of the blaze of the lamp. There were always two keepers on -the Light at one time - each being on watch half the night. Click here to read more of this article.

At many coastal lighthouses with powerful beacons, it was common for birds to strike the lantern. Minot's Ledge Light was no exception. Keeper Levi Creed reported in May 1877:

Sea and land birds of all kinds come about the light in fall and spring, and all kinds of land birds in summer if the weather is foggy or smoky. As many as 10 have been picked up at one time on the walk, but I think hundreds are killed and fall in the water.

Sea and land birds of all kinds come about the light in fall and spring, and all kinds of land birds in summer if the weather is foggy or smoky. As many as 10 have been picked up at one time on the walk, but I think hundreds are killed and fall in the water.

An 1892 article in Harper's Young People described life at Minot's Ledge:

Winter life in the Minots tower is very dreary. Its stone courses are so welded together that it has become like one huge piece of stone, and it sways under the blows of wind and wave as the trunk of a tree. But it as firm as the oak it simulates in form. The life tells terribly on the keepers. More than one has so far lost his mind as to attempt his own life, and several were removed because they became insane.

In the summer, however, the keepers take turns going ashore, leaving two out of five always there. Visitors often come off to the light. The tower is always well supplied with water, fuel, and food. The library of fifty volumes is often changed, the medicine chest is replenished, and the Light-house Inspector and the Light-house Engineer visit them at frequent intervals.

Legend has it that one keeper quit because he missed corners too much; the living quarters had nothing but round walls. Keepers also had to endure the tremendous thunder of the waves in storms. Waves have been known to break over the top of the lighthouse, and Keeper Milton Reamy claimed that a wave of 176 feet hit the tower on Christmas in 1909.

Milton Herbert Reamy, a native of Rochester, Massachusetts, who previously served for a decade at Duxbury Pier Light and Plymouth Light, was the principal keeper from 1887 to 1915. A writer for the Boston Herald described Reamy in 1888 as “on the youthful side of 40, with a curling bronze-hued beard and a clear, sharp eye.”

“The trouble with life here,” Reamy once said, “is that we have too much time to think.” Reamy's son Octavius replaced him and stayed until 1924.

Photo at right circa 1941 by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

Legend has it that one keeper quit because he missed corners too much; the living quarters had nothing but round walls. Keepers also had to endure the tremendous thunder of the waves in storms. Waves have been known to break over the top of the lighthouse, and Keeper Milton Reamy claimed that a wave of 176 feet hit the tower on Christmas in 1909.

Milton Herbert Reamy, a native of Rochester, Massachusetts, who previously served for a decade at Duxbury Pier Light and Plymouth Light, was the principal keeper from 1887 to 1915. A writer for the Boston Herald described Reamy in 1888 as “on the youthful side of 40, with a curling bronze-hued beard and a clear, sharp eye.”

“The trouble with life here,” Reamy once said, “is that we have too much time to think.” Reamy's son Octavius replaced him and stayed until 1924.

Photo at right circa 1941 by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

|

Above: An excerpt from aerial film taken by historian Edward Rowe Snow showing heavy seas striking Minots Ledge Light, circa 1950s. Courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

|

Above: Historian Edward Rowe Snow diving from the lighthouse in 1962, on his 60th birthday. Courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

|

In 1894, Capt. F. A. Mahan, an engineer with the Lighthouse Board, suggested a new system for lighthouse characteristics. As a trial of the new system, on May 1, 1894, Minots Ledge Light was given a new 12-panel rotating second-order Fresnel lens and a distinctive characteristic 1-4-3 flash—a single flash followed by an interval of three seconds, then four flashes separated by one second, then another interval of three seconds of darkness followed by three flashes again separated by one second.

Photo by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell

Someone decided that 1-4-3 stood for “I love you,” and Minots Ledge Light was soon popularly referred to as the “I Love You Light,” an appellation that has inspired numerous songs and poems.

Helen Keller wrote of passing Minots Ledge Light on her way into Boston Harbor after a trip to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1901. Although she was blind and deaf, Keller often described things as if she could see them. She wrote:

The colors warmed and deepened as we watched the beautiful, gold-tinted clouds peacefully take possession of the sky. Then came the sun, gathering the mist into silvery bands with which he wreathed the islands that lifted their heads out of the purple sea as it passed. A mighty tide of life and joy followed in its track. The ocean awoke, ships and boats of every description sprang from the waves as if by magic; and as we sighted Minot's Ledge Light, a great six-masted schooner with snowy sails passed us like a beautiful winged spirit, bound for some unknown haven beyond the bar. How delightful it was to see Minot's Ledge in the morning light. There one expects to see the ocean lashed into fury by the splendid resistance of the rocks; but as we passed the 'light' seemed to rise out of the tranquil water, like Venus from her morning bath. It seemed so near, I thought I could touch it; but I am rather glad I did not; for perhaps the lovely illusion would have been destroyed had I examined it more closely.

Helen Keller wrote of passing Minots Ledge Light on her way into Boston Harbor after a trip to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1901. Although she was blind and deaf, Keller often described things as if she could see them. She wrote:

The colors warmed and deepened as we watched the beautiful, gold-tinted clouds peacefully take possession of the sky. Then came the sun, gathering the mist into silvery bands with which he wreathed the islands that lifted their heads out of the purple sea as it passed. A mighty tide of life and joy followed in its track. The ocean awoke, ships and boats of every description sprang from the waves as if by magic; and as we sighted Minot's Ledge Light, a great six-masted schooner with snowy sails passed us like a beautiful winged spirit, bound for some unknown haven beyond the bar. How delightful it was to see Minot's Ledge in the morning light. There one expects to see the ocean lashed into fury by the splendid resistance of the rocks; but as we passed the 'light' seemed to rise out of the tranquil water, like Venus from her morning bath. It seemed so near, I thought I could touch it; but I am rather glad I did not; for perhaps the lovely illusion would have been destroyed had I examined it more closely.

Winfield Scott Thompson arrived as an assistant keeper under Octavius Reamy in 1915. The following story comes from Christina Aubin, a descendant of Thompson:

The family lighthouse story goes that one cold and stormy winter’s night, my great grandfather was alone in the lighthouse tending the light when he heard a commotion outside. So Winfield, hearing this ruckus and knowing he is not to be relieved, goes to the ladder, and lo and behold, there is a German U-boat at the bottom of the ladder with men trying to climb up the ladder.

At this time in the lighthouse service the keepers were not armed, so my great grandfather, with pretty quick thinking, grabbed a bucket and filled it with hot coals from the stove and began peppering the Germans with hot burning coals until they finally decided to give up and leave. It is said that after this incident the keepers were armed.

Right: Winfield Scott Thompson. Courtesy of Maine Lighthouse Museum.

Thompson's wife and children lived in one of the duplex houses on Government Island. At night, they could see the 1-4-3 flash of the lighthouse. Thompson's wife, Mary, told the children that their father was telling them how much he loved them each night with the "I Love You" flash.

In February 1936, Per Tornberg, principal keeper, and Manuel Figarado, a local man, were on their way to the tower in a small boat. The boat became trapped between two ice floes about 600 feet from the lighthouse. The seams on the boat split and it began to rapidly fill with water. Anthony Souza, the keeper on duty, witnessed the men's plight from the lighthouse and telephoned for help. Coast Guard crews from Hull and Scituate soon arrived and rescued the pair.

At this time in the lighthouse service the keepers were not armed, so my great grandfather, with pretty quick thinking, grabbed a bucket and filled it with hot coals from the stove and began peppering the Germans with hot burning coals until they finally decided to give up and leave. It is said that after this incident the keepers were armed.

Right: Winfield Scott Thompson. Courtesy of Maine Lighthouse Museum.

Thompson's wife and children lived in one of the duplex houses on Government Island. At night, they could see the 1-4-3 flash of the lighthouse. Thompson's wife, Mary, told the children that their father was telling them how much he loved them each night with the "I Love You" flash.

In February 1936, Per Tornberg, principal keeper, and Manuel Figarado, a local man, were on their way to the tower in a small boat. The boat became trapped between two ice floes about 600 feet from the lighthouse. The seams on the boat split and it began to rapidly fill with water. Anthony Souza, the keeper on duty, witnessed the men's plight from the lighthouse and telephoned for help. Coast Guard crews from Hull and Scituate soon arrived and rescued the pair.

Supplies and food were delivered regularly, but weather sometimes made deliveries difficult. During one bad winter in the 1930s, the keepers were down to their last can of tomatoes before the tender arrived.

A well in the lower part of the tower, filled twice yearly by the lighthouse tender, held the water supply for the keepers. One time a party of young women was being given a tour by the keepers. One asked what the well was for.

"That's our bathtub," said the keeper. It goes down 40 feet." She paused and replied, "You must be out of luck when you drop the soap."

Left: George H. Fitzpatrick, seen here holding a birthday cake during a celebration in 1936, served as principal keeper from 1936 to 1940. Photo by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

"That's our bathtub," said the keeper. It goes down 40 feet." She paused and replied, "You must be out of luck when you drop the soap."

Left: George H. Fitzpatrick, seen here holding a birthday cake during a celebration in 1936, served as principal keeper from 1936 to 1940. Photo by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

In the circa 1941 film clip above, Edward Rowe Snow is bringing a large tour group to Minot's Ledge Light. Courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

|

The Coast Guard was in charge of the lighthouse starting in 1939. The popular historian Edward Rowe Snow occasionally brought tour groups to the lighthouse.

In this 1941 photo (left), one of the keepers can be seen assisting visitors at the top of the ladder. Photo by Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell. One of the last Coast Guard keepers, Wesley B. Eaton, was left alone for extended stretches more than once. After weathering the great hurricane of 1944 in the tower alone, with waves clearing the top of the tower, Eaton decided he was through with lighthouse keeping. |

|

The lighthouse was automated and the keepers removed in 1947. The second-order Fresnel lens was replaced by a third-order lens. When the old lens was removed, it was put in one of the rooms below for temporary storage.

Vandals broke into the lighthouse and smashed sections of the lens, which had been due to go to the Boston Museum of Science. A power cable from shore -- installed in 1964 to replace a battery system -- was damaged in a storm in February 1971, and batteries were again used until the light was converted to solar power in 1983. Edmund Joseph Roche (right) was one of the last Coast Guard keepers, c. 1947. Photo courtesy of Rose Markey. |

A renovation of the tower was carried out in 1987-89. The lantern was lifted off by helicopter and subsequently cleaned, and some of the damaged upper granite blocks were removed and replaced.

The Gayle Electric Company of New Jersey, under contract to the Coast Guard, performed the work. The light was relit on August 20, 1989.

In 1992-93 the remaining keeper's house at Government Island (left), built in 1858, was restored for $200,000, raised by the nonprofit Cohasset Lightkeepers Corporation.

The house contains two apartments upstairs and a hall for community use downstairs.

In 1992-93 the remaining keeper's house at Government Island (left), built in 1858, was restored for $200,000, raised by the nonprofit Cohasset Lightkeepers Corporation.

The house contains two apartments upstairs and a hall for community use downstairs.

Today, you can drive to Government Island (on Border Street) to see a replica of the lantern room of Minots Light sitting on top of some of the granite blocks removed from the lighthouse during the renovation finished in 1989.

A third-order Fresnel lens once used in the lighthouse can be seen inside the replica lantern.

A fog bell is also on display; it was restored by local fisherman Herb Jason and his grandson John Small. Herb Jason had rescued the bell several years ago when it was about to be used for scrap.

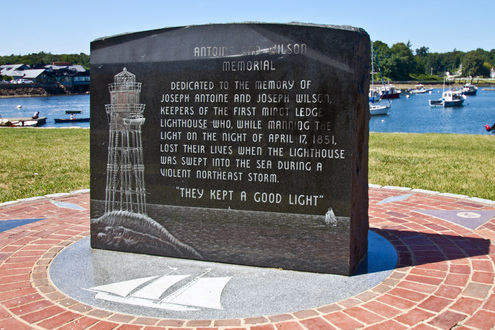

In 1997, a group of local residents began a campaign to erect a granite memorial to Joseph Antoine and Joseph Wilson, the young assistant keepers who lost their lives in 1851. The monument was finished and dedicated in 2000 on Government Island.

Under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, the lighthouse was made available for transfer to a suitable new owner. No applications were submitted by nonprofit organizations or government entities, so in June 2014 the property was put on sale to the public via online auction.

The auction ended in October 2014, and the high bidder at $222,000 was Polaroid chairman Robert “Bobby” Sager, a well-known philanthropist.

A fog bell is also on display; it was restored by local fisherman Herb Jason and his grandson John Small. Herb Jason had rescued the bell several years ago when it was about to be used for scrap.

In 1997, a group of local residents began a campaign to erect a granite memorial to Joseph Antoine and Joseph Wilson, the young assistant keepers who lost their lives in 1851. The monument was finished and dedicated in 2000 on Government Island.

Under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, the lighthouse was made available for transfer to a suitable new owner. No applications were submitted by nonprofit organizations or government entities, so in June 2014 the property was put on sale to the public via online auction.

The auction ended in October 2014, and the high bidder at $222,000 was Polaroid chairman Robert “Bobby” Sager, a well-known philanthropist.

You can see Minots Ledge Light from Government Island and other points on shore, but it is best viewed by boat.

Keepers:

(This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Isaac Dunham (1849-1850); Isaac A. Dunham (asst., 1850); John Bennett (1850-1851); Kendall Pearson (asst. c. 1851); Joseph Wilson (asst., 1850-1851); Joseph Antoine (asst., 1850-1851); Joshua Wilder (1860-1861); T. W. Ryder (asst., 1860); W. H. Sylvester (asst., 1861-1863); A. W. Williams (asst., 1860-1861); William S. Taylor (asst., 1860-1861); James J. Tower (1861-1874); Thomas Bates II (asst., 1861-1864); James D. Baxter (asst., 1863); Israel Vinal (asst., 1864-1865); Alden Simmons (asst., 1865-1870); John A. Pratt (asst., 1866-1868); Levi L. Creed (asst. 1865-1874, principal keeper 1874-1881); Albert H. Burdick (asst., 1870-1877); Wallace Willcutt (asst., 1873-1874?); John G. Hayden (asst., 1874-1877); Thomas Joseph Sheridan (asst., 1876-1880); Amiel Studley (asst., 1877-?); Joseph B. Vinal (asst., 1877-1881); Charles Davis (asst., 1879-1880); Alonzo Smith (asst., 1880-1881); Joseph A Noble (asst., 1880-1881); Nathan Hendson (?) (asst., 1881); Daniel M. Ryan (asst., 1881-1882); Frank F. Martin (asst. 1881, principal keeper 1881-1887); Frank W. Thomas (asst., 1881-1883); Lester G. Willett (asst., 1881); Joseph Enos Frates (1st asst., 1882-189?); Joseph Jason, Jr. (asst., 1883); Milton Herbert Reamy (1887-1915); George L. Lyon (asst., 1887-1889); Octavius Reamy (second assistant 1909-1910, first assistant 1910-1915, principal keeper 1915-1924); Winfield L. Creed (asst., 1892?-1894); George Holmes (asst., 1892); James Kingsley (third asst., 1893-1894); John E. Morrill (asst., 1894); Charles Grey Everett (2nd asst., 1894-1895); George Jamieson (asst., 1894-1896); Levi B. Clark (second assistant, 1905-1907, first assistant, 1907-?); ? Currier (second assistant, 1910-?); Andrew Tullock (second assistant, 1910-?); Roscoe Lopaus (second assistant, 1896-1905); Douglas H. Shepherd (assistant, c. 1913-1915); Winfield Scott Thompson (c. 1915-1918); Pierre Albert Nadeau (assistant, c. 192?-1925); Per S. Tornberg (asst., 1922-1924, keeper 1924-1936); Francis R. Macy (second assistant 1922, first assistant, 1922-1923); Otis E. Walsh (asst., c. 1930s); Anthony K. Sousa (asst., c. 1930s); George H. Fitzpatrick (asst., 1924-1927, principal keeper 1936-1940); Patrick Brides (Coast Guard, c. 1941); Robert Hamblin (Coast Guard, c. 1941); Wesley B. Eaton (1943-1944); Artemas Leslie, Jr. (Coast Guard, c. early 1940s); Julian Hatch (Coast Guard, 1946 - March 1947); BM1 Michael Pratt (Coast Guard circa 1946); George Miller (Coast Guard, circa 1946); Edmund Joseph Roche (Coast Guard, 1947)

(This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Isaac Dunham (1849-1850); Isaac A. Dunham (asst., 1850); John Bennett (1850-1851); Kendall Pearson (asst. c. 1851); Joseph Wilson (asst., 1850-1851); Joseph Antoine (asst., 1850-1851); Joshua Wilder (1860-1861); T. W. Ryder (asst., 1860); W. H. Sylvester (asst., 1861-1863); A. W. Williams (asst., 1860-1861); William S. Taylor (asst., 1860-1861); James J. Tower (1861-1874); Thomas Bates II (asst., 1861-1864); James D. Baxter (asst., 1863); Israel Vinal (asst., 1864-1865); Alden Simmons (asst., 1865-1870); John A. Pratt (asst., 1866-1868); Levi L. Creed (asst. 1865-1874, principal keeper 1874-1881); Albert H. Burdick (asst., 1870-1877); Wallace Willcutt (asst., 1873-1874?); John G. Hayden (asst., 1874-1877); Thomas Joseph Sheridan (asst., 1876-1880); Amiel Studley (asst., 1877-?); Joseph B. Vinal (asst., 1877-1881); Charles Davis (asst., 1879-1880); Alonzo Smith (asst., 1880-1881); Joseph A Noble (asst., 1880-1881); Nathan Hendson (?) (asst., 1881); Daniel M. Ryan (asst., 1881-1882); Frank F. Martin (asst. 1881, principal keeper 1881-1887); Frank W. Thomas (asst., 1881-1883); Lester G. Willett (asst., 1881); Joseph Enos Frates (1st asst., 1882-189?); Joseph Jason, Jr. (asst., 1883); Milton Herbert Reamy (1887-1915); George L. Lyon (asst., 1887-1889); Octavius Reamy (second assistant 1909-1910, first assistant 1910-1915, principal keeper 1915-1924); Winfield L. Creed (asst., 1892?-1894); George Holmes (asst., 1892); James Kingsley (third asst., 1893-1894); John E. Morrill (asst., 1894); Charles Grey Everett (2nd asst., 1894-1895); George Jamieson (asst., 1894-1896); Levi B. Clark (second assistant, 1905-1907, first assistant, 1907-?); ? Currier (second assistant, 1910-?); Andrew Tullock (second assistant, 1910-?); Roscoe Lopaus (second assistant, 1896-1905); Douglas H. Shepherd (assistant, c. 1913-1915); Winfield Scott Thompson (c. 1915-1918); Pierre Albert Nadeau (assistant, c. 192?-1925); Per S. Tornberg (asst., 1922-1924, keeper 1924-1936); Francis R. Macy (second assistant 1922, first assistant, 1922-1923); Otis E. Walsh (asst., c. 1930s); Anthony K. Sousa (asst., c. 1930s); George H. Fitzpatrick (asst., 1924-1927, principal keeper 1936-1940); Patrick Brides (Coast Guard, c. 1941); Robert Hamblin (Coast Guard, c. 1941); Wesley B. Eaton (1943-1944); Artemas Leslie, Jr. (Coast Guard, c. early 1940s); Julian Hatch (Coast Guard, 1946 - March 1947); BM1 Michael Pratt (Coast Guard circa 1946); George Miller (Coast Guard, circa 1946); Edmund Joseph Roche (Coast Guard, 1947)