History of Pemaquid Point Light, Bristol, Maine

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Pemaquid Point Light... is the delight of artists, photographers, and tourists. Pemaquid Point itself entrances both land and water visitors by the fascinating northwest-southeast varied veins of rock formation that look for all the world as if great giants had 'pulled taffy' while the rocks were in a molten condition. -- Malcolm F. Willoughby, The Boothbay Register, 1962.

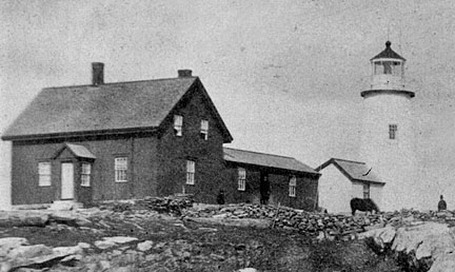

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Pemaquid Point, with its dramatic streaks of light and dark rock reaching to the sea, shaped by massive movements thousands of years ago, would be a fascinating place to visit even without its pretty white lighthouse. The spot is one of the most frequently visited attractions of the Maine coast, receiving about 100,000 visitors each year.

The name “Pemaquid” is said to have had its origins in an Abenaki Indian word for “situated far out.”

Immigrants from Bristol, England, established a settlement at Pemaquid in 1631. The village had as many as 200 people by the 1670s, but Abenaki Indians burned it during King Philip’s War. The settlement was rebuilt but suffered further attacks from the Indians and the French, and it was abandoned before 1700. It was resettled in 1729. Today, the area is part of the town of Bristol, incorporated in 1765.

The name “Pemaquid” is said to have had its origins in an Abenaki Indian word for “situated far out.”

Immigrants from Bristol, England, established a settlement at Pemaquid in 1631. The village had as many as 200 people by the 1670s, but Abenaki Indians burned it during King Philip’s War. The settlement was rebuilt but suffered further attacks from the Indians and the French, and it was abandoned before 1700. It was resettled in 1729. Today, the area is part of the town of Bristol, incorporated in 1765.

The point, at the entrance to Muscongus Bay to the east and Johns Bay to the west, was the scene of many shipwrecks through the centuries, including the 1635 wreck of the British ship Angel Gabriel.

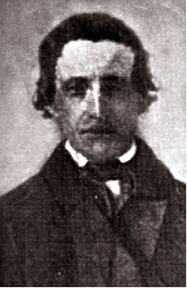

Isaac Dunham

In May 1826, as maritime trade, fishing, and the shipping of lumber were increasing in midcoast Maine, Congress appropriated $4,000 for the building of a lighthouse at Pemaquid Point. The land was purchased from Samuel and Sarah Martin—descendants of survivors of the Angel Gabriel—for $90.

Jeremiah Berry of Thomaston was contracted to build the conical rubblestone tower, along with a keeper’s dwelling, also built of stone, 20 by 34 feet with an attached kitchen, 10 by 12 feet. Berry completed construction for the sum of $2,800. The fixed white light went into service on November 29, 1827.

Forty-year-old Isaac Dunham of Bath, Maine, became the first keeper, at $350 per year. Dunham, who was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, went to sea at an early age and visited many foreign ports. During the War of 1812, he served on a privateer. Dunham moved to Maine and took up farming for some years before becoming a lighthouse keeper.

The original stone tower didn’t last long, possibly because Berry may have used salt water to mix his lime mortar. The contract for a new tower in 1835 stipulated that the mortar was “never to have been wet with salt water.” A conical stone tower was built that year by Joseph Berry of Georgetown, who was the nephew of the builder of the first tower.

Jeremiah Berry of Thomaston was contracted to build the conical rubblestone tower, along with a keeper’s dwelling, also built of stone, 20 by 34 feet with an attached kitchen, 10 by 12 feet. Berry completed construction for the sum of $2,800. The fixed white light went into service on November 29, 1827.

Forty-year-old Isaac Dunham of Bath, Maine, became the first keeper, at $350 per year. Dunham, who was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, went to sea at an early age and visited many foreign ports. During the War of 1812, he served on a privateer. Dunham moved to Maine and took up farming for some years before becoming a lighthouse keeper.

The original stone tower didn’t last long, possibly because Berry may have used salt water to mix his lime mortar. The contract for a new tower in 1835 stipulated that the mortar was “never to have been wet with salt water.” A conical stone tower was built that year by Joseph Berry of Georgetown, who was the nephew of the builder of the first tower.

A separate request for proposals was advertised in March 1835 for the installation of new lighting apparatus, with consisting of eight oil lamps and eight 14-inch reflectors, which Winslow Lewis completed following his own standard design.

Circa 1940s

The height of the 1835 tower was 30 feet to the lantern deck, with a diameter of 16 feet at the base at and 10 feet at the top. The tower was given four windows and a wooden stairway of “good sound hard pine.” Atop the tower, an octagonal, domed iron lantern was installed.

Dunham and his wife, Abigail (Cary), had five children when they moved to Pemaquid Point. A baby boy, Benjamin Franklin Dunham, was born to the keeper and his wife at the lighthouse in February 1831. The keeper’s father, Capt. Cornelius Dunham, who had commanded many vessels, died at the station in July 1835 and was buried in a small cemetery near the lighthouse.

Dunham and many of his successors kept animals, including chickens, at the light station. It appears that Dunham was also an inventor of sorts. He received a patent for a system he developed to keep lamp oil from congealing in winter, and in 1837 Congress decreed that the Treasury was authorized to adopt Dunham’s improvements. It isn’t clear how widely his invention was adopted.

Dunham, who later became the first keeper of Minot’s Ledge Light in Massachusetts, was succeeded as keeper in 1837 by Nathaniel Gamage Jr. Four years later, Gamage was replaced by Jeremiah S. Mears for political reasons. Mears was the keeper when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited in 1842 for his important survey of the area’s lighthouses. Lewis was unusually generous in his description of the Pemaquid Point tower, proclaiming the “general state of the tower good.” The keeper’s house was also “in good condition throughout.” The tower was leaky in storms, however, and 11 panes of glass in the lantern were broken. By this time, the lantern held 10 lamps and corresponding reflectors.

Dunham and his wife, Abigail (Cary), had five children when they moved to Pemaquid Point. A baby boy, Benjamin Franklin Dunham, was born to the keeper and his wife at the lighthouse in February 1831. The keeper’s father, Capt. Cornelius Dunham, who had commanded many vessels, died at the station in July 1835 and was buried in a small cemetery near the lighthouse.

Dunham and many of his successors kept animals, including chickens, at the light station. It appears that Dunham was also an inventor of sorts. He received a patent for a system he developed to keep lamp oil from congealing in winter, and in 1837 Congress decreed that the Treasury was authorized to adopt Dunham’s improvements. It isn’t clear how widely his invention was adopted.

Dunham, who later became the first keeper of Minot’s Ledge Light in Massachusetts, was succeeded as keeper in 1837 by Nathaniel Gamage Jr. Four years later, Gamage was replaced by Jeremiah S. Mears for political reasons. Mears was the keeper when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited in 1842 for his important survey of the area’s lighthouses. Lewis was unusually generous in his description of the Pemaquid Point tower, proclaiming the “general state of the tower good.” The keeper’s house was also “in good condition throughout.” The tower was leaky in storms, however, and 11 panes of glass in the lantern were broken. By this time, the lantern held 10 lamps and corresponding reflectors.

A new lantern was installed in 1856, and the multiple lamps and reflectors were replaced by a fourth-order Fresnel lens with a single lamp. The original keeper’s house was replaced by a wood-frame dwelling during the following year.

A fog bell was added to the station in 1897, and steam engines were installed to operate the bell. Apparently this system didn’t work very well, because in 1899 a striking machine was installed, powered by a hand-cranked clockwork mechanism. The bell house built in 1897 was adapted with the addition of a tall tower to enclose the weights for the new mechanism.

Keeper Joseph Lawler and his wife, Sophronia, welcomed a baby girl, Susie, born in the keeper's house in 1868. Marcus A. Hanna, who was later acclaimed for a heroic rescue at Cape Elizabeth, succeeded Lawler in 1869 and stayed until 1873.

William L. Sartell spent a decade as keeper at the station (1873–83), followed by Charles A. Dolliver’s 16-year stay (1883–99) and Clarence K. Marr’s 23-year stint (1899–1922). Marr, born in 1852, was the son and brother of keepers at Hendricks Head Light. Before coming to Pemaquid Point, he was assistant keeper at the Cuckolds Fog Signal Station.

Keeper Joseph Lawler and his wife, Sophronia, welcomed a baby girl, Susie, born in the keeper's house in 1868. Marcus A. Hanna, who was later acclaimed for a heroic rescue at Cape Elizabeth, succeeded Lawler in 1869 and stayed until 1873.

William L. Sartell spent a decade as keeper at the station (1873–83), followed by Charles A. Dolliver’s 16-year stay (1883–99) and Clarence K. Marr’s 23-year stint (1899–1922). Marr, born in 1852, was the son and brother of keepers at Hendricks Head Light. Before coming to Pemaquid Point, he was assistant keeper at the Cuckolds Fog Signal Station.

On September 16, 1903, while Marr was keeper, the captain of the fishing schooner George F. Edmunds tried to run for South Bristol Harbor in a gale. The vessel was driven by a strong gust into the rocks near Pemaquid Point and was dashed to pieces. The captain and 13 crew members died in the wreck; only two were saved. The captain of another schooner, the Sadie and Lillie, also died near Pemaquid Point in the same storm.

Herbert Robinson became keeper after Marr retired. The wedding of his daughter, Edith, later took place on the porch of the keeper’s house.

Leroy S. Elwell was keeper in 1934 when the light became one of the earliest in Maine to be converted to automatic acetylene gas operation.

Sidney Baldwin wrote in Casting Off from Boothbay Harbor: “There was a wail of grief all along the coast when the government in its policy of cutting down the Lighthouse Service and transferring it to the Coast Guard electrified Pemaquid Light. There is a big keeper’s house standing empty. The light flashes by day and night with no one to guard it. The necessary work of cleaning the lenses and making minor repairs is done by a visiting light keeper.”

Leroy S. Elwell was keeper in 1934 when the light became one of the earliest in Maine to be converted to automatic acetylene gas operation.

Sidney Baldwin wrote in Casting Off from Boothbay Harbor: “There was a wail of grief all along the coast when the government in its policy of cutting down the Lighthouse Service and transferring it to the Coast Guard electrified Pemaquid Light. There is a big keeper’s house standing empty. The light flashes by day and night with no one to guard it. The necessary work of cleaning the lenses and making minor repairs is done by a visiting light keeper.”

The house didn't remain empty for very long. In March 1940, residents voted at a town meeting to authorize Bristol’s selectmen to purchase the property, except for the lighthouse tower. The town made annual payments for four years, totaling $1,639. The surrounding property became the town’s Lighthouse Park, and the keeper’s house eventually was converted into the Fishermen’s Museum.

Circa 1940s

The museum opened in 1972 and has been operated since then by volunteers from the local area.

The museum houses exhibits on the history of the local fishing and lobstering industries, as well as pictures of all the lighthouses on the Maine coast and a fourth-order Fresnel lens from Baker Island Light.

The Pemaquid Group of Artists added an art gallery to Lighthouse Park in 1960.

The roof of the bell house and its weight tower were badly damaged in a storm in April 1991, and later that year Hurricane Bob destroyed the structures.

Circa 1975 (U.S. Coast Guard)

The structures were reconstructed in the following year. The bell house, with exhibits inside, is opened to the public in summer. The Coast Guard had removed the fog bell in 1937, but a smaller bell was later acquired and displayed on the bell house.

The large parking lot and the museum are open seven days a week in the summer for a small fee. For more information, or to donate to the Fishermen's Museum, contact:

Fishermen's Museum

Pemaquid Point Road

New Harbor, Maine 04554

(207) 677-2494

The large parking lot and the museum are open seven days a week in the summer for a small fee. For more information, or to donate to the Fishermen's Museum, contact:

Fishermen's Museum

Pemaquid Point Road

New Harbor, Maine 04554

(207) 677-2494

In May 2000, the lighthouse tower was licensed by the Coast Guard to the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF). Around the same time, the Coast Guard hired P & G Masonry and Scaffold of Scarborough, Maine, and workers replaced lantern glass and painted the tower.

Under the leadership of Dick Melville, a local resident, a chapter of ALF, the Friends of Pemaquid Point Lighthouse, was formed. The group soon restored the entryway to the tower and began holding open houses. “I think such an exceptional part of our history should be maintained and be open to the public,” Melville told the Portland Press Herald. Melville died in 2005, but other dedicated volunteers have carried on his legacy.

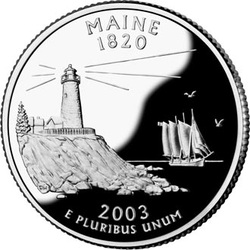

Pemaquid Point Light became the first lighthouse ever to ever appear on American currency in 2003, when its image appeared on the official Maine quarter.

By the twenty-first century, the tower’s healthy outward appearance belied the problems within; considerable water intrusion had caused deterioration of the tower’s mortar. It became apparent that significant restoration was needed in a hurry.

Pemaquid Point Light became the first lighthouse ever to ever appear on American currency in 2003, when its image appeared on the official Maine quarter.

By the twenty-first century, the tower’s healthy outward appearance belied the problems within; considerable water intrusion had caused deterioration of the tower’s mortar. It became apparent that significant restoration was needed in a hurry.

In February 2007, Lowe’s Companies and the National Trust for Historic Preservation announced that the lighthouse would receive $50,000 toward a $106,000 restoration. In June 2007, personnel from Building Conservation Associates (BCA), analyzed the tower’s coatings, work that was made possible by a $10,000 “New Century Community Program” historic preservation grant from the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

The remaining $46,000 needed for restoration was raised by the volunteers of Friends of Pemaquid Point Lighthouse, much of it a dollar at a time at open houses.

A report by BCA included recommendations for the removal of the exterior coatings. ALF hired J. B. Leslie Masonry Contractors of Berwick, Maine, to remove the coatings and the tower’s deteriorated mortar, and to repoint and paint the tower. Jim Leslie, president of J. B. Leslie Masonry, commented during the work:, “The original masons who built this lighthouse were highly skilled workers. The expert method in which they placed the stonework and tapered the tower is quite evident.”

The tower’s repointing, which utilized the same type of natural cement-based material used during the original construction, was completed by the end of July 2007. A new coat of paint was applied in August.

ALF’s executive director, Bob Trapani, commented, “The minute you drive or walk into Pemaquid Point Park, the lighthouse commands your attention in the wake of its restoration. It’s like a shining exclamation point on a seascape of blue.”

Volunteers of the Friends of Pemaquid Point Lighthouse (a chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation) manage the tower only. Volunteers open the tower in season (Memorial Day to Columbus Day) to the public every day from 10:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. There is no charge to climb the tower but donations are welcomed.

A one-bedroom apartment in the keeper’s house is available for weekly vacation rentals. For information, call Newcastle Square Vacation Rentals at (207) 563-6500.

A report by BCA included recommendations for the removal of the exterior coatings. ALF hired J. B. Leslie Masonry Contractors of Berwick, Maine, to remove the coatings and the tower’s deteriorated mortar, and to repoint and paint the tower. Jim Leslie, president of J. B. Leslie Masonry, commented during the work:, “The original masons who built this lighthouse were highly skilled workers. The expert method in which they placed the stonework and tapered the tower is quite evident.”

The tower’s repointing, which utilized the same type of natural cement-based material used during the original construction, was completed by the end of July 2007. A new coat of paint was applied in August.

ALF’s executive director, Bob Trapani, commented, “The minute you drive or walk into Pemaquid Point Park, the lighthouse commands your attention in the wake of its restoration. It’s like a shining exclamation point on a seascape of blue.”

Volunteers of the Friends of Pemaquid Point Lighthouse (a chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation) manage the tower only. Volunteers open the tower in season (Memorial Day to Columbus Day) to the public every day from 10:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. There is no charge to climb the tower but donations are welcomed.

A one-bedroom apartment in the keeper’s house is available for weekly vacation rentals. For information, call Newcastle Square Vacation Rentals at (207) 563-6500.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Isaac Dunham (1827-1837); Nathaniel Gamage, Jr. (1837-1841); Jeremiah S. Mears (1841-1845); Ephraim Tibbetts (1845-1849); Robert Curtis (1849-1853); Samuel C. Tibbetts (1853-1858); John Fossett (1858-1861); Joseph Lawler (1861-1869); Marcus A. Hanna (1869-1873); William L. Sartell (1873-1883); Charles A. Dolliver (1883-1899); Clarence E. Marr (1899-1922); Herbert Robinson (1922-1928); Leroy S. Elwell (1928-1934).

Isaac Dunham (1827-1837); Nathaniel Gamage, Jr. (1837-1841); Jeremiah S. Mears (1841-1845); Ephraim Tibbetts (1845-1849); Robert Curtis (1849-1853); Samuel C. Tibbetts (1853-1858); John Fossett (1858-1861); Joseph Lawler (1861-1869); Marcus A. Hanna (1869-1873); William L. Sartell (1873-1883); Charles A. Dolliver (1883-1899); Clarence E. Marr (1899-1922); Herbert Robinson (1922-1928); Leroy S. Elwell (1928-1934).