History of Colchester Reef Light, Shelburne, Vermont

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Perhaps the best known lighthouse of New England's "west coast," Colchester Reef Light was originally located about a mile offshore from Colchester Point on Lake Champlain, a vital waterway bordering New York, Vermont, and Quebec.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

A report of the Lighthouse Board in 1869 stated, "It is recommended that an appropriation be made for the erection of a light-house on Colchester Reef, South Hero Island, or in the vicinity." The light was established in 1871, at a cost of $20,000, to mark a group of three dangerous shoals.

Similar Second Empire designs were used for Rhode Island's lighthouses at Pomham Rocks, Sabin Point, and Rose Island. The design for Colchester Reef Lighthouse was submitted by Albert R. Dow, a graduate engineer from the University of Vermont. His design was chosen over many entries in a national design competition run by the Lighthouse Service.

Herman Melaney was the first of nine keepers at Colchester Reef, and he remained for 11 years. The lighthouse had four bedrooms on its second floor, and a kitchen and living room on the first floor. The fixed red light was visible for 11 miles. The original sixth-order Fresnel lens remains in place.

Similar Second Empire designs were used for Rhode Island's lighthouses at Pomham Rocks, Sabin Point, and Rose Island. The design for Colchester Reef Lighthouse was submitted by Albert R. Dow, a graduate engineer from the University of Vermont. His design was chosen over many entries in a national design competition run by the Lighthouse Service.

Herman Melaney was the first of nine keepers at Colchester Reef, and he remained for 11 years. The lighthouse had four bedrooms on its second floor, and a kitchen and living room on the first floor. The fixed red light was visible for 11 miles. The original sixth-order Fresnel lens remains in place.

A fog bell was sounded by winding a clockwork mechanism, and it was struck every 20 seconds when fog limited the light's visibility to less than three miles. No doubt the keepers and their families had many sleepless nights.

Left: This photo from April 1923 shows ice damage. Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

A storm in January 1873 shook the lighthouse, damaging the lens. $5,000 was spent to rip-rap the base of the building, affording it more protection in storms.

An assistant keeper, Chandler McNeil, drowned on May 21, 1879, while trying to assist a disabled boat. McNeil was left with no oars and attempted unsuccessfully to swim ashore.

On January 29, 1888, a baby, Myrtle Button, was born at the lighthouse. When his wife, Harriet, went into labor, Keeper Walter Button sent for a doctor by ringing the fog bell, a signal to his assistant on shore. Unfortunately, as they tried to cross the ice to the lighthouse, the doctor and assistant keeper were carried by ice floes several miles to the north, and were lucky to escape with their lives. Harriet Button had her baby without benefit of a doctor, but all worked out well.

To help provide food for his family Keeper Button kept a fruit and vegetable garden, along with a cow and a pair of horses, on Sunset Island about a half mile away. The children were often sent to work in the garden. Walter Button would blow a horn he had made from a conch shell as a signal to the children if a storm was approaching while they were on Sunset Island.

Many lighthouses have been home to cats and dogs, but Keeper Button had slightly more unusual pets. One day a pair of squirrels mysteriously appeared on the rocks outside the lighthouse. The keeper caught the squirrels and put them in a cage. They gradually grew tame and were given the run of the lighthouse. When visitors asked how the squirrels arrived at Colchester Reef, Button would answer, "They made sails of their tails and sailed on a cake of ice."

A storm in January 1873 shook the lighthouse, damaging the lens. $5,000 was spent to rip-rap the base of the building, affording it more protection in storms.

An assistant keeper, Chandler McNeil, drowned on May 21, 1879, while trying to assist a disabled boat. McNeil was left with no oars and attempted unsuccessfully to swim ashore.

On January 29, 1888, a baby, Myrtle Button, was born at the lighthouse. When his wife, Harriet, went into labor, Keeper Walter Button sent for a doctor by ringing the fog bell, a signal to his assistant on shore. Unfortunately, as they tried to cross the ice to the lighthouse, the doctor and assistant keeper were carried by ice floes several miles to the north, and were lucky to escape with their lives. Harriet Button had her baby without benefit of a doctor, but all worked out well.

To help provide food for his family Keeper Button kept a fruit and vegetable garden, along with a cow and a pair of horses, on Sunset Island about a half mile away. The children were often sent to work in the garden. Walter Button would blow a horn he had made from a conch shell as a signal to the children if a storm was approaching while they were on Sunset Island.

Many lighthouses have been home to cats and dogs, but Keeper Button had slightly more unusual pets. One day a pair of squirrels mysteriously appeared on the rocks outside the lighthouse. The keeper caught the squirrels and put them in a cage. They gradually grew tame and were given the run of the lighthouse. When visitors asked how the squirrels arrived at Colchester Reef, Button would answer, "They made sails of their tails and sailed on a cake of ice."

In the winter. Lake Champlain frequently froze over so that visitors often arrived at the lighthouse on foot or in horse-drawn sleighs.

From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

August Lorenz was keeper from 1909 to 1931, the longest stint of any keeper. He would row several miles to shore for supplies. One time in the winter he became frozen to the seat in his boat and had to chop himself free.

Once, while Lorenz was keeper, a huge ice floe crashed right through the kitchen and opened an enormous hole in the house. The keeper's dory was torn away but he managed to retrieve it from a floating cake of ice by snagging it with a long pole.

From 1933, when it was deactivated, until 1952, the Colchester Reef Lighthouse fell into disrepair. In July 1952, Electra Havemeyer Webb, who had inherited a fortune in the sugar cane industry and founded the Shelburne Museum, purchased the lighthouse from Paul and Lorraine Besette, who had bought it from the Coast Guard for $50. They had intended to use the lumber from the lighthouse for the building of a home on shore.

Once, while Lorenz was keeper, a huge ice floe crashed right through the kitchen and opened an enormous hole in the house. The keeper's dory was torn away but he managed to retrieve it from a floating cake of ice by snagging it with a long pole.

From 1933, when it was deactivated, until 1952, the Colchester Reef Lighthouse fell into disrepair. In July 1952, Electra Havemeyer Webb, who had inherited a fortune in the sugar cane industry and founded the Shelburne Museum, purchased the lighthouse from Paul and Lorraine Besette, who had bought it from the Coast Guard for $50. They had intended to use the lumber from the lighthouse for the building of a home on shore.

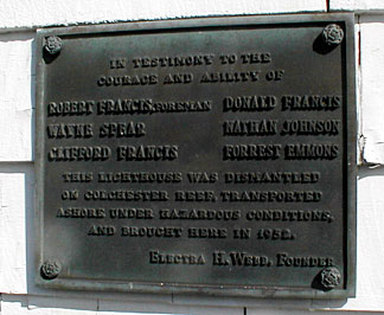

Before the building was dismantled, every part was photographed and number for identification. A crew of five men dismantled the lighthouse and took it to Shelburne by barge, reassembling it in less than a month.

The museum's insurance company would insure the crew for work on shore only, so the men resigned and were reinstated after the operation was finished. The lighthouse was placed on a new foundation at the museum and much restoration was done over the next several years.

In June 1961, the lighthouse was struck by lightning. Museum staff and the Shelburne Volunteer Fire Department were able to quickly put out the fire, which resulted in only minor damage.

Today, the lighthouse is one of 37 buildings on the grounds of the museum that has been called "New England's Smithsonian."

Inside the lighthouse, which stands near the landlocked side-wheeler steamboat Ticonderoga, there are exhibits on Lake Champlain history, steamboats, and lighthouse life.

In June 1961, the lighthouse was struck by lightning. Museum staff and the Shelburne Volunteer Fire Department were able to quickly put out the fire, which resulted in only minor damage.

Today, the lighthouse is one of 37 buildings on the grounds of the museum that has been called "New England's Smithsonian."

Inside the lighthouse, which stands near the landlocked side-wheeler steamboat Ticonderoga, there are exhibits on Lake Champlain history, steamboats, and lighthouse life.

After more than 70 years in darkness, the lighthouse was relit with a solar-powered light, largely through the efforts of the Coast Guard's Burlington base and lighthouse historian George Clifford of Plattsburgh, New York.

Clifford jokes that now, with the lighthouse illuminated at night, partyers aboard the Ticonderoga will be able to navigate their way home safely.

A $130,000 rehabilitation of the lighthouse's base got underway in March 2009, thanks largely to a donation by a descendant of one of the light's keepers. When the work is completed in the summer of 2009, the lighthouse will be handicapped accessible.

The Shelburne Museum is a must-see for lighthouse buffs and anybody interested in nineteenth century life in New England.

A $130,000 rehabilitation of the lighthouse's base got underway in March 2009, thanks largely to a donation by a descendant of one of the light's keepers. When the work is completed in the summer of 2009, the lighthouse will be handicapped accessible.

The Shelburne Museum is a must-see for lighthouse buffs and anybody interested in nineteenth century life in New England.

Keepers: Herman Melaney (1871-1882); Chandler McNeil (?-1879); Walter M. Button (1882-1888 and 1890-1892); August Pare (1888-1889); James Wakefield, Jr. (1889-1890); Chester F. Button (1901-1908); Willam H. Howard (1908-1909); August Lorenz (or Lorenze) (1909-1931); Joseph Aubin (1931-1933).