History of Penfield Reef Lighthouse, Fairfield, Connecticut

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

The shoal that extends more than a mile from Penfield Beach in Fairfield was long a scourge to mariners traveling by on Long Island Sound or heading to the harbors at Black Rock and Bridgeport.

In 1864, the steamer Rip Van Winkle ran into the rocks with a large number of passengers and a major tragedy was narrowly averted. In the winter of 1866-67 alone, four more vessels ran into the shoal. Local merchants and mariners clamored for a lighthouse to guide vessels safely around the treacherous area.

Captain D. C. Constable of the Lighthouse Board called the Cows “the most dangerous locality, during fogs and snow-storms, upon Long Island sound.” Benjamin Penfield, who had been navigating the sound for 40 years, added, “Vessels are stranded here every year, and our increasing commerce calls attention to something so important for its protection.”

Tradition holds that this was once solid land that supported the pasturing of cattle, hence the names “Cows” and “Calves” for two prominent rocky parts of the shoal.

Captain D. C. Constable of the Lighthouse Board called the Cows “the most dangerous locality, during fogs and snow-storms, upon Long Island sound.” Benjamin Penfield, who had been navigating the sound for 40 years, added, “Vessels are stranded here every year, and our increasing commerce calls attention to something so important for its protection.”

Tradition holds that this was once solid land that supported the pasturing of cattle, hence the names “Cows” and “Calves” for two prominent rocky parts of the shoal.

On April 22, 1868, Joseph Lederle, lighthouse engineer for the Third District, wrote the following to Admiral W. B. Shubrick of the Lighthouse Board:

Having carefully examined the locality referred to, I fully agree with the views of the light-house inspector of this district, and the petitioners, as to the necessity of having a light to guide clear of the shoal extending from Fairfield, about two miles distant.

This dangerous shoal is now marked by a day beacon and two buoys, sufficient guides for vessels passing by during daytime. At night the mariner is left without any mark to warn him of the danger; hence the many disasters which occur at this shoal. . .

The extreme end of the shoal is marked by three points, which are known as the Cows, Huncher Rock, and Penfield Reef. On Huncher Rock is the Black Rock beacon. . .

It is respectfully recommended to put the proposed light-house on Penfield Reef… The tower connected with the keeper’s dwelling is recommended to be built on the plan approved by the board for the Hudson river stations. It is further recommended to furnish the station with a powerful fog signal.

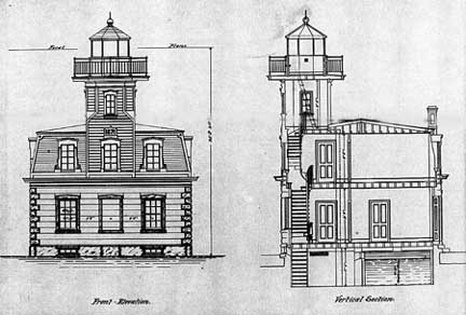

The granite riprap foundation for the lighthouse was 108 feet in diameter.

Early 1900s

On top of that, an 18-foot-tall pier was constructed of

cut granite in nine courses, 48 3/4 feet in diameter at the base and 46

1/2 feet at the top. The conical ring of granite was filled with

concrete, with a cavity left near the top to serve as the lighthouse’s

basement. The pier was based on the one designed for Race Rock

Light in Fisher’s Island Sound, New York. The 28-foot square dwelling

with a mansard roof was built centrally on the pier. Between 1898 and

1902, in excess of 1,200 tons of granite riprap were added as extra

protection around the foundation.

Race Rock, Penfield Reef and Stratford Shoal (1877) would prove to be among the last offshore masonry lighthouses on masonry foundations built in the U.S. before the use of cast iron towers on cylindrical cast iron caissons came into vogue.

In 1874 the Lighthouse Board reported:

The dwelling and tower of this station have been satisfactorily completed, and the light was exhibited the first time on January 16, 1874. A fog bell, struck by machinery, has been established at this station.

Race Rock, Penfield Reef and Stratford Shoal (1877) would prove to be among the last offshore masonry lighthouses on masonry foundations built in the U.S. before the use of cast iron towers on cylindrical cast iron caissons came into vogue.

In 1874 the Lighthouse Board reported:

The dwelling and tower of this station have been satisfactorily completed, and the light was exhibited the first time on January 16, 1874. A fog bell, struck by machinery, has been established at this station.

The granite walls of the first floor are lined with brick. The second floor originally contained four bedrooms, while the first consisted of a kitchen, living room, and oil room.

U.S. Coast Guard

The second story and light tower

are of wood-frame construction and the tower at the watchroom level is

octagonal. Above that is an octagonal cast-iron lantern, which

originally held a fourth-order Fresnel lens. The lens revolved

with the use of a clockwork mechanism that had to be wound by the

keepers. A flashing red light was exhibited, 51 feet above mean

high water.

The first keeper, George Tomlinson, remained only two years. Turnover at the offshore station was great, with many keepers and assistants remaining only a year or two. William Jones was head keeper starting in 1880 at a salary of $500 yearly, and his wife, Pauline, was his assistant at $400 per year.

Neil Martin, formerly at Race Rock and Stamford Harbor, was keeper from 1882 to 1891. His wife Jane also served as an assistant keeper during some of that time. Jane Martin died in March of 1886, and Keeper Martin received a letter from the Lighthouse Depot in Tompkinsville, NY, coldly informing him, “Find a competent man to take your place, and then leave of absence to attend the burial of your wife is hereby granted you.”

It was often harrowing getting to and from the lighthouse, especially in winter. Nelson B. Allen, an assistant keeper, had a hair-raising experience in late January of 1888. The New York Times of January 30 reported:

He came ashore in the afternoon after medicine for his wife, and started on his return at 5 o’clock. His boat got wedged between two large cakes of ice which were drifting southward. He was unable to release it. After floating about for five hours he was rescued by the steamer City of New Haven and transferred to a tug which had been sent out in search of him. He was exhausted, and his limbs were frost-bitten. This afternoon he was taken to the light-house.

The saddest incident in the lighthouse’s history took place nearly three decades later. On December 22, 1916, Keeper Fred A. Jordan (sometimes spelled Jordon) left the lighthouse at twenty minutes past noon to row ashore. There were high seas and strong winds, but the keeper badly wanted to join his family for Christmas and to give his hand-made presents to his children. Assistant Keeper Rudolph Iten watched from the lighthouse as Jordan pushed his boat through the waves.

The first keeper, George Tomlinson, remained only two years. Turnover at the offshore station was great, with many keepers and assistants remaining only a year or two. William Jones was head keeper starting in 1880 at a salary of $500 yearly, and his wife, Pauline, was his assistant at $400 per year.

Neil Martin, formerly at Race Rock and Stamford Harbor, was keeper from 1882 to 1891. His wife Jane also served as an assistant keeper during some of that time. Jane Martin died in March of 1886, and Keeper Martin received a letter from the Lighthouse Depot in Tompkinsville, NY, coldly informing him, “Find a competent man to take your place, and then leave of absence to attend the burial of your wife is hereby granted you.”

It was often harrowing getting to and from the lighthouse, especially in winter. Nelson B. Allen, an assistant keeper, had a hair-raising experience in late January of 1888. The New York Times of January 30 reported:

He came ashore in the afternoon after medicine for his wife, and started on his return at 5 o’clock. His boat got wedged between two large cakes of ice which were drifting southward. He was unable to release it. After floating about for five hours he was rescued by the steamer City of New Haven and transferred to a tug which had been sent out in search of him. He was exhausted, and his limbs were frost-bitten. This afternoon he was taken to the light-house.

The saddest incident in the lighthouse’s history took place nearly three decades later. On December 22, 1916, Keeper Fred A. Jordan (sometimes spelled Jordon) left the lighthouse at twenty minutes past noon to row ashore. There were high seas and strong winds, but the keeper badly wanted to join his family for Christmas and to give his hand-made presents to his children. Assistant Keeper Rudolph Iten watched from the lighthouse as Jordan pushed his boat through the waves.

About a hundred yards from the lighthouse, Jordan’s boat capsized.

Rudolph Iten

He clung to the boat

and signaled for Iten to lower the station’s remaining boat and come to

his aid. Iten tried valiantly to do this, but the steadily

increasing waves and wind made it impossible to launch the boat.

He finally got underway about 1 p.m., but by that time Jordan had

drifted a mile and a half to the southwest. Iten said later:I

did my level best to reach him, but I hadn’t pulled more than half a

mile when the wind changed to the southwest, making a head-wind and an

outgoing tide, against which I couldn’t move the heavy boat. I

had to give up, and returned to the station in a regular gale.

From the station I sent distress signals to passing ships, but none

answered. At three o’clock I lost sight of the drifting

boat. The poor fellow’s body wasn’t found until three months

later. He was a fine fellow, was Fred.

Iten was absolved of any blame for Jordan’s death. He was promoted to head keeper and would remain for more than a decade. A May 14, 1922, article by F. A. Barrow in the Bridgeport Sunday Post offered an intimate glimpse at life at Penfield Reef. Iten lived at the lighthouse with two assistants at that time, Walter Harper and Arthur Bender. Each of the men, all World War I veterans, got eight days off each month. When Barrow entered the building, “a lively little dog came bounding and barking a welcome.” This was Penfield, or Pen for short.

The conversation upon Barrow’s arrival centered around the “merits of various washing and scouring powders,” prompting the writer to remark, “I would suggest to any suffragette looking for a husband who could keep house while she was attending business or lectures, that she might do well to choose a lighthouse keeper.” Barrow asked the keeper how the work was divided between the men. He replied, “We stand watches. This is my watch. At one in the morning Arthur goes on duty. The regular work we share, washing, scrubbing and cooking; and we can all cook, too – you wait and see.”

Barrow learned later that “the boast in regard to cooking was not an idle one” when he was treated to “steak and noodles a la Penfield.” Dessert was a “beautiful pink cake” that Arthur Bender had won in Fairfield.

Barrow described the living room, with green walls decorated with photos of all the Allied generals of World War I. The room was furnished with a table, several chairs, a desk and a “graphonola” with records. Reading material on hand included poems by Burns and Longfellow, and Poe’s The Gold Bug.

Iten was absolved of any blame for Jordan’s death. He was promoted to head keeper and would remain for more than a decade. A May 14, 1922, article by F. A. Barrow in the Bridgeport Sunday Post offered an intimate glimpse at life at Penfield Reef. Iten lived at the lighthouse with two assistants at that time, Walter Harper and Arthur Bender. Each of the men, all World War I veterans, got eight days off each month. When Barrow entered the building, “a lively little dog came bounding and barking a welcome.” This was Penfield, or Pen for short.

The conversation upon Barrow’s arrival centered around the “merits of various washing and scouring powders,” prompting the writer to remark, “I would suggest to any suffragette looking for a husband who could keep house while she was attending business or lectures, that she might do well to choose a lighthouse keeper.” Barrow asked the keeper how the work was divided between the men. He replied, “We stand watches. This is my watch. At one in the morning Arthur goes on duty. The regular work we share, washing, scrubbing and cooking; and we can all cook, too – you wait and see.”

Barrow learned later that “the boast in regard to cooking was not an idle one” when he was treated to “steak and noodles a la Penfield.” Dessert was a “beautiful pink cake” that Arthur Bender had won in Fairfield.

Barrow described the living room, with green walls decorated with photos of all the Allied generals of World War I. The room was furnished with a table, several chairs, a desk and a “graphonola” with records. Reading material on hand included poems by Burns and Longfellow, and Poe’s The Gold Bug.

The bedrooms on the second floor were “comfortably but not luxuriously furnished” with “cot-beds” all neatly made.

U.S. Coast Guard

The writer asked Assistant Keeper Bender how the

men dealt with the ice on the station in winter. Bender explained that

they sprinkled ashes wherever they walked outside on the station to

avoid sliding right into the sound.

For heat, the lighthouse had three stoves, with eight tons of coal and three cords of wood for winter fuel.

The lighthouse’s sturdy construction served it well in the brutal storms that occasionally swept through Long Island Sound. Iten described the violent gale of October 24, 1917:

The waves dashed against the place and shook it to the foundations. They broke above the pier, smashed glass and sashes, and the spray went clean over the light. Wild? I’ll say it was. I had a new motor-boat that my father-in-law and I had purchased together. We had taken the engine out for an overhauling. Well, the waves caught that nice, new boat and made kindling wood of it… I was mighty glad at that time that the light was on a good foundation.

For heat, the lighthouse had three stoves, with eight tons of coal and three cords of wood for winter fuel.

The lighthouse’s sturdy construction served it well in the brutal storms that occasionally swept through Long Island Sound. Iten described the violent gale of October 24, 1917:

The waves dashed against the place and shook it to the foundations. They broke above the pier, smashed glass and sashes, and the spray went clean over the light. Wild? I’ll say it was. I had a new motor-boat that my father-in-law and I had purchased together. We had taken the engine out for an overhauling. Well, the waves caught that nice, new boat and made kindling wood of it… I was mighty glad at that time that the light was on a good foundation.

A few years later another writer visited Iten, and a conversation in the wee hours of the morning turned decidedly macabre.

The view from Fayerweather Island in Bridgeport.

“They say that

all lighthouse keepers are mad,” said Iten as a preface to the

following chilling tale, told against the background of the whispering

wind and the gentle wash of the waves.

You ask if there has ever been anything in the nature of a supernatural occurrence at this lighthouse. Well, all light keepers are more or less hard-boiled and not given over to stretches of imagination. While I don’t deny or admit the theory of ghosts, something happened here one night that seemed to point to the establishment of the fact that there are such things as supernatural visitations.

Iten recounted the accidental death of Keeper Jordan in December 1916, then continued:

Some days later on what was one of the worst nights in the history of Penfield, and the waves were dashing over the lantern, I was awakened – I was off duty – by a strange feeling that someone was in my room. Sitting up I distinctly saw a gray, phosphorescent figure emerging from the room formerly occupied by Fred Jordan. It hovered at the top of the stairs, and then disappeared in the darkness below. Thinking it was the assistant keeper I called to know if anything was the matter, but he answered me from the lens room that all was well.

Much puzzled, I went downstairs and to my consternation I saw lying on the table the log-book of the lighthouse, with the page recording the drowning of Poor Jordan staring me in the face!

This is the only time the book has been taken from its place by other hands than mine or my assistants, and as to how it got on the table and lay open with the entry about Jordan will always remain a mystery to us here. I have seen the semblance of the figure several times since and so have the others, and we are all prepared to take an affidavit to that effect. Something comes here, that we are positive. There is an old saying, ‘What the Reef takes, the Reef will give back.’ Poor Jordan’s body was recovered not long after his drowning, and in the pocket of his coat was found a note addressed to me – which he probably forgot to leave before he started on his fateful ride in that rough sea – instructing me to complete the entries of that morning – the day he died – as they were not brought up to date.

An undated article in the Bridgeport Public Library claims that, on stormy nights, “the specter of the reef is said to be flitting among the rocks, poised on the rail of the gallery that surrounds the lantern or swaying, as if in agony, among the black and jagged rocks that surround the base of the light.” The article tells the story of a power yacht that ran into trouble on the rocks but was “piloted through the breakers to safety by a strange man who suddenly appeared amid the surf creaming over the rocks… in a row-boat.”

And then there were the two boys who were fishing near the reef when their canoe capsized, throwing them into the sea. A man appeared “from out of the rocks” and pulled them to safety. When they came to, they entered the lighthouse expecting to thank their savior, but he was nowhere to be found.

Keeper Iten said that he and the other keepers had performed 27 rescues in his years at Penfield Reef, including canoeists trying to cross the shoal and exhausted swimmers. The keepers once hauled a motorboat full of people on the reef and repaired the boat’s rudder. For their trouble, the men were given an underwhelming reward of one dollar. “Of course, we never accept monetary remuneration,” said Iten, “but the value put by the leader of the party on our lives and his company – at one dollar – well, it was amusing.”

In September 1916, nine barges of the Blue Line Company had piled up on part of the reef, a location henceforth known as the Blue Line Graveyard. Another time, a coal freighter ran right into the lighthouse, dislodging some of the riprap stones and making the keepers think an earthquake was in progress. And Iten told the story of the skipper of a small boat that hit the reef in broad daylight and then proceeded to lodge an official complaint about the light being “too dim.”

You ask if there has ever been anything in the nature of a supernatural occurrence at this lighthouse. Well, all light keepers are more or less hard-boiled and not given over to stretches of imagination. While I don’t deny or admit the theory of ghosts, something happened here one night that seemed to point to the establishment of the fact that there are such things as supernatural visitations.

Iten recounted the accidental death of Keeper Jordan in December 1916, then continued:

Some days later on what was one of the worst nights in the history of Penfield, and the waves were dashing over the lantern, I was awakened – I was off duty – by a strange feeling that someone was in my room. Sitting up I distinctly saw a gray, phosphorescent figure emerging from the room formerly occupied by Fred Jordan. It hovered at the top of the stairs, and then disappeared in the darkness below. Thinking it was the assistant keeper I called to know if anything was the matter, but he answered me from the lens room that all was well.

Much puzzled, I went downstairs and to my consternation I saw lying on the table the log-book of the lighthouse, with the page recording the drowning of Poor Jordan staring me in the face!

This is the only time the book has been taken from its place by other hands than mine or my assistants, and as to how it got on the table and lay open with the entry about Jordan will always remain a mystery to us here. I have seen the semblance of the figure several times since and so have the others, and we are all prepared to take an affidavit to that effect. Something comes here, that we are positive. There is an old saying, ‘What the Reef takes, the Reef will give back.’ Poor Jordan’s body was recovered not long after his drowning, and in the pocket of his coat was found a note addressed to me – which he probably forgot to leave before he started on his fateful ride in that rough sea – instructing me to complete the entries of that morning – the day he died – as they were not brought up to date.

An undated article in the Bridgeport Public Library claims that, on stormy nights, “the specter of the reef is said to be flitting among the rocks, poised on the rail of the gallery that surrounds the lantern or swaying, as if in agony, among the black and jagged rocks that surround the base of the light.” The article tells the story of a power yacht that ran into trouble on the rocks but was “piloted through the breakers to safety by a strange man who suddenly appeared amid the surf creaming over the rocks… in a row-boat.”

And then there were the two boys who were fishing near the reef when their canoe capsized, throwing them into the sea. A man appeared “from out of the rocks” and pulled them to safety. When they came to, they entered the lighthouse expecting to thank their savior, but he was nowhere to be found.

Keeper Iten said that he and the other keepers had performed 27 rescues in his years at Penfield Reef, including canoeists trying to cross the shoal and exhausted swimmers. The keepers once hauled a motorboat full of people on the reef and repaired the boat’s rudder. For their trouble, the men were given an underwhelming reward of one dollar. “Of course, we never accept monetary remuneration,” said Iten, “but the value put by the leader of the party on our lives and his company – at one dollar – well, it was amusing.”

In September 1916, nine barges of the Blue Line Company had piled up on part of the reef, a location henceforth known as the Blue Line Graveyard. Another time, a coal freighter ran right into the lighthouse, dislodging some of the riprap stones and making the keepers think an earthquake was in progress. And Iten told the story of the skipper of a small boat that hit the reef in broad daylight and then proceeded to lodge an official complaint about the light being “too dim.”

William Hardwick came to Penfield Reef as keeper in 1932 after time at Stratford Shoal, Peck Ledge, Bridgeport Harbor, and Faulkner’s Island lights.

William Hardwick

During much of the Coast Guard era, three men were assigned to Penfield Reef, with two on duty at one time. The men had two weeks on followed by one week off. One of the last keepers was C. J. Stites, who later became Bridgeport’s senior deputy harbormaster. In a 1983 article in the Fairfield Citizen-News, he said that visitors were generally not allowed, but sometimes people did stop by with food or bits of news.

The crew put a sign saying, “Send newspapers” in a window. “Newspapers were worth their weight in gold,” Stites said. A lobsterman sometimes passed by and threw the day’s paper near the lighthouse door, and one time a helicopter flew by and someone dumped a load of old newspapers on the roof.

Stites said holidays at the lighthouse were tough, especially the Fourth of July when the men could hear music from Bridgeport’s Seaside Park. Hardwick was a native of Shipley in Yorkshire, England, and had come to the U.S. with his family in 1885. Eight years later, he went to sea as a teenager on a fishing boat in the North Sea.

Hardwick’s travels as a fisherman and the merchant marine took him far and wide.According to a 1941 article in the Bridgeport Sunday Post, Hardwick claimed that once, off Sicily, he heard the song of the Sirens – a traditional bad omen. Two days later his vessel was struck by a giant wave and 22 crewmen died. In late December 1935 at Penfield Reef, Hardwick said that he heard the Sirens for a second time, a low, eerie music that froze him in the tower. The area was ravaged the next day by a blizzard, with a Japanese steamer going aground on Penfield Reef and scores of other wrecks in the vicinity.

The crew put a sign saying, “Send newspapers” in a window. “Newspapers were worth their weight in gold,” Stites said. A lobsterman sometimes passed by and threw the day’s paper near the lighthouse door, and one time a helicopter flew by and someone dumped a load of old newspapers on the roof.

Stites said holidays at the lighthouse were tough, especially the Fourth of July when the men could hear music from Bridgeport’s Seaside Park. Hardwick was a native of Shipley in Yorkshire, England, and had come to the U.S. with his family in 1885. Eight years later, he went to sea as a teenager on a fishing boat in the North Sea.

Hardwick’s travels as a fisherman and the merchant marine took him far and wide.According to a 1941 article in the Bridgeport Sunday Post, Hardwick claimed that once, off Sicily, he heard the song of the Sirens – a traditional bad omen. Two days later his vessel was struck by a giant wave and 22 crewmen died. In late December 1935 at Penfield Reef, Hardwick said that he heard the Sirens for a second time, a low, eerie music that froze him in the tower. The area was ravaged the next day by a blizzard, with a Japanese steamer going aground on Penfield Reef and scores of other wrecks in the vicinity.

During much of the Coast Guard era, three men were assigned to Penfield Reef, with two on duty at one time.

U.S. Coast Guard

The men had two weeks on followed by one week off. One of the last keepers was C. J. Stites, who later became Bridgeport’s senior deputy harbormaster. In a 1983 article in the Fairfield Citizen-News, he said that visitors were generally not allowed, but sometimes people did stop by with food or bits of news.

The crew put a sign saying, “Send newspapers” in a window. “Newspapers were worth their weight in gold,” Stites said. A lobsterman sometimes passed by and threw the day’s paper near the lighthouse door, and one time a helicopter flew by and someone dumped a load of old newspapers on the roof.

Stites said holidays at the lighthouse were tough, especially the Fourth of July when the men could hear music from Bridgeport’s Seaside Park. Clark Ellison was also among the last Coast Guard keepers, and his memories dispel many notions of the romance of lighthouse life:

Most people believed it an adventure or possibly even romantic to be a ‘wickie.’ It was not. Most of the time it was nothing more than boring. When I was there the second floor had a small bedroom for the officer in charge and a large bedroom for the other men, a bathroom and a radio room, and the ladder up to the light. The light had an electric lamp and motor to turn the light, but the motor never worked. The light was kept in motion by a stack of weights on cables that had to be wound up on a drum, and the weights would lower through the floor and through a gear box that would spin the light, which floated in a brass vat of mercury. Or so I was told, as one could not see the mercury. If the weights touched the floor they would spin and twist the cable causing the motion to stop.

The radio almost never worked as it was an old tube type and tubes were hard to come by. We had to change at least one a week and [the Coast Guard station at] Eaton's Neck did not want spend any unnecessary funds on the light, so we only received two or three a month. And then once in a while they would send a few extra so we could do our daily reports.

Water came from a 180-foot buoy tender through a hose that was hauled by hand across the water -- lots of fun when the tide was flowing. Do not ask where the septic field was as it did not exist. The washer and dryer were in the lowest level of the light also. On the first floor there was a kitchen and generator room. Penfield was the only light in our group that had shore power, so we only had one generator. How I hated the fog. The horn rattled the whole building, and my quarters were right above the horn.

In the summer we fished and it was generally good. but in the winter the wind blew through the building. The curtains in the crew’s quarters were seldom still. The dark green tiles on the galley deck were polished and waxed again and again as there was nothing else to do. The few times I managed to steal a TV from Eaton's Neck we did have TV to watch but as soon as I left, the guys from Eaton's Neck would retrieve the TV.

The water quality was such that it was boiled before drinking it. After a while we had five-gallon coolers with water, and we drained the cistern, scraped and repainted it. Doubt that I would fit through that little hole anymore.

Most people are interested in the ghost. I never believed in ghosts and had never even heard the story when I encountered him the first time. Stanley Blake and I were on the light and it was late at night. I heard Stan walking up the stairs and decided to get up and have coffee with him, thinking it was just before sunrise. I got out of bed and pulled on a pair of shorts and as I came out of the door I noticed there was no one coming up the stairs after all. It was at that time that Stan opened the door to his room and it was obvious he just woke up also. He said, ‘I did not know you were up and when I heard you I decided to get up and have some coffee.’

He and I slinked around the light looking for who was intruding and found no one. We were both sure someone had walked up the stairs as you could hear each step creak, one at a time, as they always did when someone came up. Now understand -- we had visitors that would let themselves in at all hours of the day and night, but they always announced their arrival when they entered the kitchen. We had more visitations after that but did not get up to seek the ghost in person.

After nearly a century of resident keepers, Penfield Reef Light was automated in 1971. The Coast Guard had planned to replace the structure with a pipe tower but local residents objected. With the help of Congressman Lowell Weicker and State Representative Stewart McKinney the venerable lighthouse was saved.

The light remains an active aid to navigation and an automated fog signal is still in use. The Fresnel lens has been replaced by a modern lens. In 2000 it was reported that the lantern was in danger of collapsing into the structure, but the Coast Guard has had the structure stabilized.

In April 2007, it was announced that the lighthouse would be available to a suitable new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. On July 29, 2008, Beacon Preservation, Inc., of Ansonia, Connecticut, received notice that the organization had submitted a "superior" application and had been recommended as the new owners. Then, after a lengthy dispute concerning the ownership of the submerged land under the lighthouse, ownership reverted to the federal government in the summer of 2011.

In 2011 and again in 2013, the lighthouse went up for sale via online auction. Both times the auctions were canceled by the GSA.

Hurricane Sandy did significant damage to the structure in October 2012. In June 2014, it was announced that the Coast Guard would have repairs carried out at the lighthouse. The work was completed in late 2015. Along with needed repairs, the roof was changed back to its historic rusty red color.

A new auction was held and a high bid of $282,345 was accepted on October 10, 2016.

Penfield Reef Light can be viewed distantly from Fairfield Beach and from the Black Rock section of Bridgeport. At low tide it's possible to walk much of the way to the light, but keep in mind that local legend has it that a family of seven once tried this and was never seen again.

The crew put a sign saying, “Send newspapers” in a window. “Newspapers were worth their weight in gold,” Stites said. A lobsterman sometimes passed by and threw the day’s paper near the lighthouse door, and one time a helicopter flew by and someone dumped a load of old newspapers on the roof.

Stites said holidays at the lighthouse were tough, especially the Fourth of July when the men could hear music from Bridgeport’s Seaside Park. Clark Ellison was also among the last Coast Guard keepers, and his memories dispel many notions of the romance of lighthouse life:

Most people believed it an adventure or possibly even romantic to be a ‘wickie.’ It was not. Most of the time it was nothing more than boring. When I was there the second floor had a small bedroom for the officer in charge and a large bedroom for the other men, a bathroom and a radio room, and the ladder up to the light. The light had an electric lamp and motor to turn the light, but the motor never worked. The light was kept in motion by a stack of weights on cables that had to be wound up on a drum, and the weights would lower through the floor and through a gear box that would spin the light, which floated in a brass vat of mercury. Or so I was told, as one could not see the mercury. If the weights touched the floor they would spin and twist the cable causing the motion to stop.

The radio almost never worked as it was an old tube type and tubes were hard to come by. We had to change at least one a week and [the Coast Guard station at] Eaton's Neck did not want spend any unnecessary funds on the light, so we only received two or three a month. And then once in a while they would send a few extra so we could do our daily reports.

Water came from a 180-foot buoy tender through a hose that was hauled by hand across the water -- lots of fun when the tide was flowing. Do not ask where the septic field was as it did not exist. The washer and dryer were in the lowest level of the light also. On the first floor there was a kitchen and generator room. Penfield was the only light in our group that had shore power, so we only had one generator. How I hated the fog. The horn rattled the whole building, and my quarters were right above the horn.

In the summer we fished and it was generally good. but in the winter the wind blew through the building. The curtains in the crew’s quarters were seldom still. The dark green tiles on the galley deck were polished and waxed again and again as there was nothing else to do. The few times I managed to steal a TV from Eaton's Neck we did have TV to watch but as soon as I left, the guys from Eaton's Neck would retrieve the TV.

The water quality was such that it was boiled before drinking it. After a while we had five-gallon coolers with water, and we drained the cistern, scraped and repainted it. Doubt that I would fit through that little hole anymore.

Most people are interested in the ghost. I never believed in ghosts and had never even heard the story when I encountered him the first time. Stanley Blake and I were on the light and it was late at night. I heard Stan walking up the stairs and decided to get up and have coffee with him, thinking it was just before sunrise. I got out of bed and pulled on a pair of shorts and as I came out of the door I noticed there was no one coming up the stairs after all. It was at that time that Stan opened the door to his room and it was obvious he just woke up also. He said, ‘I did not know you were up and when I heard you I decided to get up and have some coffee.’

He and I slinked around the light looking for who was intruding and found no one. We were both sure someone had walked up the stairs as you could hear each step creak, one at a time, as they always did when someone came up. Now understand -- we had visitors that would let themselves in at all hours of the day and night, but they always announced their arrival when they entered the kitchen. We had more visitations after that but did not get up to seek the ghost in person.

After nearly a century of resident keepers, Penfield Reef Light was automated in 1971. The Coast Guard had planned to replace the structure with a pipe tower but local residents objected. With the help of Congressman Lowell Weicker and State Representative Stewart McKinney the venerable lighthouse was saved.

The light remains an active aid to navigation and an automated fog signal is still in use. The Fresnel lens has been replaced by a modern lens. In 2000 it was reported that the lantern was in danger of collapsing into the structure, but the Coast Guard has had the structure stabilized.

In April 2007, it was announced that the lighthouse would be available to a suitable new owner under the guidelines of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. On July 29, 2008, Beacon Preservation, Inc., of Ansonia, Connecticut, received notice that the organization had submitted a "superior" application and had been recommended as the new owners. Then, after a lengthy dispute concerning the ownership of the submerged land under the lighthouse, ownership reverted to the federal government in the summer of 2011.

In 2011 and again in 2013, the lighthouse went up for sale via online auction. Both times the auctions were canceled by the GSA.

Hurricane Sandy did significant damage to the structure in October 2012. In June 2014, it was announced that the Coast Guard would have repairs carried out at the lighthouse. The work was completed in late 2015. Along with needed repairs, the roof was changed back to its historic rusty red color.

A new auction was held and a high bid of $282,345 was accepted on October 10, 2016.

Penfield Reef Light can be viewed distantly from Fairfield Beach and from the Black Rock section of Bridgeport. At low tide it's possible to walk much of the way to the light, but keep in mind that local legend has it that a family of seven once tried this and was never seen again.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

George Tomlinson (1874-1876); Sidney B. Thompson (assistant 1874); Charles Nichols (assistant 1874-1875); Edward Burroughs (1875-1876); Augustus Eddy (assistant 1876, head keeper 1876-1880); George H. Lord (assistant 1876); Edward Matthewson (assistant 1876-1877); Charles Sommers (assistant 1877-1878); David Tuttle (assistant 1878-1879); Chauncy D. Norton (assistant 1879-1880); William Jones (1880-1882); Pauline Jones (assistant 1880-1882); Neil Martin (1882-1891); Jane Martin (assistant 1883-1886?); Charles Grantham (assistant 1886); John Daniel Luding (assistant 1886-1887); Charles Wells (assistant 1887); F. B. Couch (assistant 1887); William R. Holley (assistant 1887); Nelson B. Allen (assistant 1888); George W. Beckwith (assistant 1888-1890); James A. Hobson (assistant 1890-1899); William H. Haynes (1891-1908); Elmer Vincent Newton (assistant 1906-1908, head keeper 1908-?); James Boyce (assistant 1903-1905); Arthur Eddy (assistant 1905); Joseph Trombley (assistant 1905); John T. Dixon (assistant 1899-1900); Joseph D. Meade (assistant 1900-1901); George A. Porter (assistant 1901-1903); Joseph D. Burke (assistant 1908); Sidney Williams (assistant 1908-1909); Lawrence Farmington (?) (assistant 1909-1910); Jerome McDougall (assistant 1910); Ernest Hatcher (?) (assistant 1910); A. B. Miller (assistant 1910-1911); Albert J. Brown (assistant 1911); Jesse Orton (assistant 1911-1912); W. H. Oliver (assistant 1912-?); Elmer Newton (assistant 1906-1908; principal keeper1908-1914); Frederick Jordan (1914-1916); Rudolph Iten (assistant c. 1916-1917, principal keeper 1917-1919 and 1920-1926); Charles Reuter (1919-1920); Arthur Bender (1st assistant c. 1920s); Walter Harper (2nd assistant c. 1920s); William Chapel (assistant c.1925); Fred White (c. 1926-1928); George Petzolt (c. 1930-1941); William Hardwick (assistant? 1932-1941); William Shackley (1941-1946); Jose Fernandez (1948–1953), John Chilly (at least 1958), Luis A. Ortiz (at least 1959–1961), Robert G. Jackson (1961–1964), John P. Jennings (1964–1965), William E. Arzt (1965–1967), Joseph E. Kember (1967), Clinton J. Stites (1967–1968), Gregory W. Janson, Jr. (1968), James E. Samuel (1968); Patrick R. Tomlinson (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); Dale R. Seivert (1969–1970); Clark Ellison (Coast Guard officer in charge, 1970-1971).

George Tomlinson (1874-1876); Sidney B. Thompson (assistant 1874); Charles Nichols (assistant 1874-1875); Edward Burroughs (1875-1876); Augustus Eddy (assistant 1876, head keeper 1876-1880); George H. Lord (assistant 1876); Edward Matthewson (assistant 1876-1877); Charles Sommers (assistant 1877-1878); David Tuttle (assistant 1878-1879); Chauncy D. Norton (assistant 1879-1880); William Jones (1880-1882); Pauline Jones (assistant 1880-1882); Neil Martin (1882-1891); Jane Martin (assistant 1883-1886?); Charles Grantham (assistant 1886); John Daniel Luding (assistant 1886-1887); Charles Wells (assistant 1887); F. B. Couch (assistant 1887); William R. Holley (assistant 1887); Nelson B. Allen (assistant 1888); George W. Beckwith (assistant 1888-1890); James A. Hobson (assistant 1890-1899); William H. Haynes (1891-1908); Elmer Vincent Newton (assistant 1906-1908, head keeper 1908-?); James Boyce (assistant 1903-1905); Arthur Eddy (assistant 1905); Joseph Trombley (assistant 1905); John T. Dixon (assistant 1899-1900); Joseph D. Meade (assistant 1900-1901); George A. Porter (assistant 1901-1903); Joseph D. Burke (assistant 1908); Sidney Williams (assistant 1908-1909); Lawrence Farmington (?) (assistant 1909-1910); Jerome McDougall (assistant 1910); Ernest Hatcher (?) (assistant 1910); A. B. Miller (assistant 1910-1911); Albert J. Brown (assistant 1911); Jesse Orton (assistant 1911-1912); W. H. Oliver (assistant 1912-?); Elmer Newton (assistant 1906-1908; principal keeper1908-1914); Frederick Jordan (1914-1916); Rudolph Iten (assistant c. 1916-1917, principal keeper 1917-1919 and 1920-1926); Charles Reuter (1919-1920); Arthur Bender (1st assistant c. 1920s); Walter Harper (2nd assistant c. 1920s); William Chapel (assistant c.1925); Fred White (c. 1926-1928); George Petzolt (c. 1930-1941); William Hardwick (assistant? 1932-1941); William Shackley (1941-1946); Jose Fernandez (1948–1953), John Chilly (at least 1958), Luis A. Ortiz (at least 1959–1961), Robert G. Jackson (1961–1964), John P. Jennings (1964–1965), William E. Arzt (1965–1967), Joseph E. Kember (1967), Clinton J. Stites (1967–1968), Gregory W. Janson, Jr. (1968), James E. Samuel (1968); Patrick R. Tomlinson (Coast Guard, 1968-1969); Dale R. Seivert (1969–1970); Clark Ellison (Coast Guard officer in charge, 1970-1971).