History of Highland Light, North Truro, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

When Truro, Massachusetts, the second most northerly town on Cape Cod, was first settled as Pamet in 1646, it was part of a larger area known as Nauset. Pamet’s name was changed to Truro (after a Cornish town it was said to resemble) when it was incorporated as a separate town in 1709.

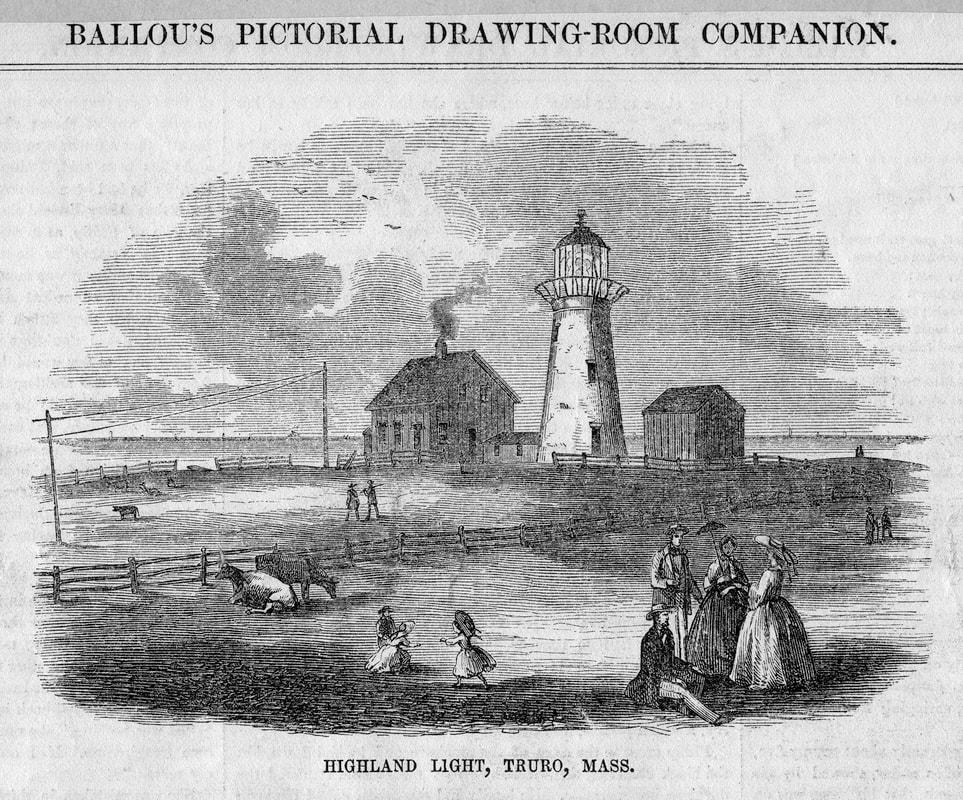

Highland Light circa 1856

Truro developed a whaling fleet based at Pamet River Harbor, which comprised nine sloops by the early 1800s.

In its early years, mariners knew Pamet as Dangerfield because of the frequent wrecks off its shores. A treacherous spot called Peaked Hill Bars, a graveyard for many ships, lies about a mile northeast of the lighthouse site. The 64-gun British warship Somerset, immortalized in Longfellow’s poem The Ride of Paul Revere, famously struck the bars in 1778; 21 lives were lost.

In 1792, with these dangers in mind and ever-increasing maritime traffic around Cape Cod, the Massachusetts Humane Society and the Boston Marine Society requested that the governor of Massachusetts ask the U.S. Congress to fund a lighthouse “upon the High Land adjacent to Cape Cod Harbour.” There was no immediate action.

In 1794, Reverend James Freeman wrote that there were more ships wrecked near the eastern shore of Truro than on any other part of Cape Cod. "A light house," he went on to say, "near the Clay Pounds should Congress think proper to erect one, would prevent many of these fatal accidents."

In its early years, mariners knew Pamet as Dangerfield because of the frequent wrecks off its shores. A treacherous spot called Peaked Hill Bars, a graveyard for many ships, lies about a mile northeast of the lighthouse site. The 64-gun British warship Somerset, immortalized in Longfellow’s poem The Ride of Paul Revere, famously struck the bars in 1778; 21 lives were lost.

In 1792, with these dangers in mind and ever-increasing maritime traffic around Cape Cod, the Massachusetts Humane Society and the Boston Marine Society requested that the governor of Massachusetts ask the U.S. Congress to fund a lighthouse “upon the High Land adjacent to Cape Cod Harbour.” There was no immediate action.

In 1794, Reverend James Freeman wrote that there were more ships wrecked near the eastern shore of Truro than on any other part of Cape Cod. "A light house," he went on to say, "near the Clay Pounds should Congress think proper to erect one, would prevent many of these fatal accidents."

Having no luck with their appeal to the governor, the Boston Marine Society appointed a committee of three men in February 1796 to draft a petition directly to Congress.

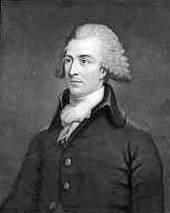

Tench Coxe (1755-1824)

The Massachusetts Humane Society and the Salem Marine Society were also included in the petition, which brought about almost immediate action.

Congress appropriated $8,000 for a lighthouse on May 17, 1796. Tench Coxe, commissioner of Revenue and supervisor of federal lighthouse operations at the time, asked General Benjamin Lincoln—customs collector for Boston and local lighthouse superintendent—to procure a suitable site for the lighthouse by “gift or purchase.”

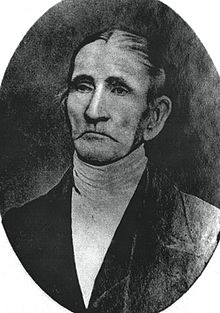

Lincoln traveled to Cape Cod to select the site. It was the view of mariners that the lighthouse should be built on the Highlands or Clay Pounds of Truro, where the high bluffs—rising nearly 150 feet from the beach—would augment the height and visibility of the light.

Congress appropriated $8,000 for a lighthouse on May 17, 1796. Tench Coxe, commissioner of Revenue and supervisor of federal lighthouse operations at the time, asked General Benjamin Lincoln—customs collector for Boston and local lighthouse superintendent—to procure a suitable site for the lighthouse by “gift or purchase.”

Lincoln traveled to Cape Cod to select the site. It was the view of mariners that the lighthouse should be built on the Highlands or Clay Pounds of Truro, where the high bluffs—rising nearly 150 feet from the beach—would augment the height and visibility of the light.

Lincoln concurred, explaining his choice of a site in a letter to Coxe on June 9, 1796:

Benjamin Lincoln (1733-1810)

Because the lands here are pretty good and are not so sandy as to be liable to be blown away by the high gales of wind too often experienced on this Cape... As the light-house must be made of wood the soil will be good for its foundation... Fresh water can easily be obtained within the ten acres. The land will summer a cow after a garden shall be taken off for which there is some pretty good land.

Ten acres of land at the Highlands were purchased from a Truro resident, Isaac Small, for $110—$100 for the land plus and $10 for the “right of passing” over Small’s adjoining land. The bluff wasn’t the highest in the area, but it appears the deal was made with an eye toward Small’s appointment as the light’s first keeper.

In a letter, Tench Coxe wrote, “The land bought for the site of the Light House was purchased of Mr. Small who owns the adjoining grounds. It is probable therefore, that economy in regard to fencing and salary may be made by appointing him.” There were other applicants, but Small won the job.

Ten acres of land at the Highlands were purchased from a Truro resident, Isaac Small, for $110—$100 for the land plus and $10 for the “right of passing” over Small’s adjoining land. The bluff wasn’t the highest in the area, but it appears the deal was made with an eye toward Small’s appointment as the light’s first keeper.

In a letter, Tench Coxe wrote, “The land bought for the site of the Light House was purchased of Mr. Small who owns the adjoining grounds. It is probable therefore, that economy in regard to fencing and salary may be made by appointing him.” There were other applicants, but Small won the job.

A 45-foot, octagonal wooden tower, the first lighthouse on Cape Cod and the twentieth in the United States, was built about 500 feet from the edge of the bluff, where it exhibiting exhibited its light from 160 feet above mean high water.

The light went into service on November 15, 1797. A one-story dwelling for the keeper was also constructed, along with a barn, an oil storage shed, and a well. The total cost of the buildings was $7,257.56.

Because of fears that mariners might confuse Highland Light with Boston Light (a single fixed light at that time), some consideration was given to the possibility of a double light at the Cape Cod station. Instead, Lincoln and Coxe determined that the lighthouse would be the first in the nation to have a flashing light. A rotating “eclipser” was designed and built by James Bailey Jr. According to a notice that was issued to the press, the eclipser revolved around the spider lamp (a simple pan of oil with several wicks) once in 80 seconds, and the light would be hidden from view for 30 seconds during each revolution.

The weather affected the eclipser's clockwork machinery, and Small complained that the timing was irregular. The machinery didn’t run as long as it was supposed to on a single winding, which required Small to wind it twice during each night. In recognition of this, in 1798 his salary was raised from $150 to $200 yearly. The eclipser continued to behave erratically. It was finally removed in 1812, when the lighthouse received a newly patented Winslow Lewis system of multiple Argand-type lamps and reflectors. The 1797 tower was in such poor condition—“wretchedly constructed,” according to the local lighthouse superintendent—that it had to be greatly altered before the new equipment could be installed.

Before Lewis’s lighting apparatus could be put into service, te height of the tower was reduced by 17 feet and a new lantern, 10 feet high, was installed. The new equipment was in use by February 1812. Boston Light became a revolving light in 1811, so there was no fear that the two would be hard to tell apart. Highland Light would remain fixed white until 1901.

Constant Hopkins, who was nearly 70 years old, succeeded Small as keeper in October 1812. Hopkins died less than five years later and was succeeded by John Grocier (or Grozier). Isaac Small continued farming on the adjacent land. Grocier complained about Small’s obtrusive cattle, saying they “brake the ground up so that it blows away.”

An 1828 report stated that the 1797 wooden lighthouse was "very imperfect -- is easily wracked by the winds, which shakes the lantern so much as to break the glass very frequently." After a congressional appropriation of $5,000 in March 1831, a new 35-foot round brick lighthouse tower was erected close to the site of the original lighthouse. The lighthouse and a new brick dwelling were built under contract by Winslow Lewis, at a cost of $4,162. The date the work was completed isn’t clear, but it was apparently sometime in 1833.

Because of fears that mariners might confuse Highland Light with Boston Light (a single fixed light at that time), some consideration was given to the possibility of a double light at the Cape Cod station. Instead, Lincoln and Coxe determined that the lighthouse would be the first in the nation to have a flashing light. A rotating “eclipser” was designed and built by James Bailey Jr. According to a notice that was issued to the press, the eclipser revolved around the spider lamp (a simple pan of oil with several wicks) once in 80 seconds, and the light would be hidden from view for 30 seconds during each revolution.

The weather affected the eclipser's clockwork machinery, and Small complained that the timing was irregular. The machinery didn’t run as long as it was supposed to on a single winding, which required Small to wind it twice during each night. In recognition of this, in 1798 his salary was raised from $150 to $200 yearly. The eclipser continued to behave erratically. It was finally removed in 1812, when the lighthouse received a newly patented Winslow Lewis system of multiple Argand-type lamps and reflectors. The 1797 tower was in such poor condition—“wretchedly constructed,” according to the local lighthouse superintendent—that it had to be greatly altered before the new equipment could be installed.

Before Lewis’s lighting apparatus could be put into service, te height of the tower was reduced by 17 feet and a new lantern, 10 feet high, was installed. The new equipment was in use by February 1812. Boston Light became a revolving light in 1811, so there was no fear that the two would be hard to tell apart. Highland Light would remain fixed white until 1901.

Constant Hopkins, who was nearly 70 years old, succeeded Small as keeper in October 1812. Hopkins died less than five years later and was succeeded by John Grocier (or Grozier). Isaac Small continued farming on the adjacent land. Grocier complained about Small’s obtrusive cattle, saying they “brake the ground up so that it blows away.”

An 1828 report stated that the 1797 wooden lighthouse was "very imperfect -- is easily wracked by the winds, which shakes the lantern so much as to break the glass very frequently." After a congressional appropriation of $5,000 in March 1831, a new 35-foot round brick lighthouse tower was erected close to the site of the original lighthouse. The lighthouse and a new brick dwelling were built under contract by Winslow Lewis, at a cost of $4,162. The date the work was completed isn’t clear, but it was apparently sometime in 1833.

In the early 1840s, Highland Light became a battleground between the old guard of lighthouse administration and technology—represented by Winslow Lewis and Stephen Pleasanton (the Treasury official who oversaw the U.S. Lighthouse Establshment 1820-52) —and the new wave of reformers led by the civil engineer I. W. P. Lewis, who happened to be Winslow Lewis’s nephew.

Stephen Pleasanton (1776-1855)

I. W. P. Lewis had studied civil engineering and entered lighthouse work with the help and encouragement of his uncle. Eventually, the two became competitors for lighthouse contracts, and the ambitious I. W. P. sometimes bid below his actual costs in order to win contracts over his uncle.

In the summer of 1840, the younger Lewis installed a new cast-iron lantern and lighting apparatus at Highland Light. He replaced his uncle’s apparatus with a system of lamps and reflectors based on an English model. The lamps and reflectors were more carefully positioned and focused than they had been previously, and they were installed in such a way that they couldn’t be easily moved out of proper alignment.

When he began the lantern installation, I. W. P. Lewis found that the tower’s window frames, doorframes, and wooden stairs were all rotten and had to be replaced. He also found that the inner brick walls were laid without mortar, and that the walls were filled with sand. The tower had no foundation and merely rested on the ground, and the mortar was so bad in the upper part of the tower that 13 feet had to be removed from the top.I. W. P. Lewis had to rebuild substantially rebuild the tower his uncle had built in order to install the new lantern, at a total cost of $5,919. An inspection by the local superintendent in 1842 described the new apparatus as “in perfect order,” showing a “brilliant light.”Jesse Holbrook, who became keeper in 1840, reported that when the old stairway was removed from the tower, it was found that "the interior of the wall was filled with rubbish, and the brick work apparently thrown together without any regard to form, there being neither mortar nor bond."

I. W. P. Lewis, at the request of the secretary of the Treasury, authored a scathing 1843 report on New England’s lighthouses. The report eventually led to the formation of the new U.S. Lighthouse Board in 1852, two years after the death of Winslow Lewis. I. W. P. Lewis, who died in 1855 at the age of 47, has been called the father of American’s modern lighthouse system.

Shipwrecks in the vicinity were less frequent after the establishment of the lighthouse, but they were not eliminated. One of the worst wrecks near the station was that of the British bark Josephus in a thick fog in April 1849. Two local fishermen went out in a dory in an attempt to aid the crew, but the would-be lifesavers themselves perished in the high seas.

It appeared at first that the entire crew of 16 had died, but Keeper Enoch Hamilton returned hours after the wreck to find that two men had washed ashore and were still alive. Hamilton and a companion carried the men to the keeper’s house, where they spent the night. One of the survivors of the Josephus, John Jasper, later became the captain of an ocean liner. When his vessel passed Highland Light, he would dip the flag as a signal of respect for Keeper Hamilton.

In the summer of 1840, the younger Lewis installed a new cast-iron lantern and lighting apparatus at Highland Light. He replaced his uncle’s apparatus with a system of lamps and reflectors based on an English model. The lamps and reflectors were more carefully positioned and focused than they had been previously, and they were installed in such a way that they couldn’t be easily moved out of proper alignment.

When he began the lantern installation, I. W. P. Lewis found that the tower’s window frames, doorframes, and wooden stairs were all rotten and had to be replaced. He also found that the inner brick walls were laid without mortar, and that the walls were filled with sand. The tower had no foundation and merely rested on the ground, and the mortar was so bad in the upper part of the tower that 13 feet had to be removed from the top.I. W. P. Lewis had to rebuild substantially rebuild the tower his uncle had built in order to install the new lantern, at a total cost of $5,919. An inspection by the local superintendent in 1842 described the new apparatus as “in perfect order,” showing a “brilliant light.”Jesse Holbrook, who became keeper in 1840, reported that when the old stairway was removed from the tower, it was found that "the interior of the wall was filled with rubbish, and the brick work apparently thrown together without any regard to form, there being neither mortar nor bond."

I. W. P. Lewis, at the request of the secretary of the Treasury, authored a scathing 1843 report on New England’s lighthouses. The report eventually led to the formation of the new U.S. Lighthouse Board in 1852, two years after the death of Winslow Lewis. I. W. P. Lewis, who died in 1855 at the age of 47, has been called the father of American’s modern lighthouse system.

Shipwrecks in the vicinity were less frequent after the establishment of the lighthouse, but they were not eliminated. One of the worst wrecks near the station was that of the British bark Josephus in a thick fog in April 1849. Two local fishermen went out in a dory in an attempt to aid the crew, but the would-be lifesavers themselves perished in the high seas.

It appeared at first that the entire crew of 16 had died, but Keeper Enoch Hamilton returned hours after the wreck to find that two men had washed ashore and were still alive. Hamilton and a companion carried the men to the keeper’s house, where they spent the night. One of the survivors of the Josephus, John Jasper, later became the captain of an ocean liner. When his vessel passed Highland Light, he would dip the flag as a signal of respect for Keeper Hamilton.

The naturalist and author Henry David Thoreau visited Highland Light several times in the 1850s. Thoreau found the lighthouse "a neat building, in apple pie order."

Henry David Thoreau

In his book, Cape Cod, he wrote:

The keeper entertained us handsomely in his solitary little ocean house. He was a man of singular patience and intelligence, who, when our queries struck him, rang as clear as a bell in response. The light-house lamp a few feet distant shone full into my chamber, and made it bright as day, so I knew exactly how the Highland Light bore all that night, and I was in no danger of being wrecked... I thought as I lay there, half-awake and half-asleep, looking upward through the window at the lights above my head, how many sleepless eyes from far out on the ocean stream -- mariners of all nations spinning their yarns through the various watches of the night -- were directed toward my couch.

(You can read the entire chapter by clicking here.)

The keeper entertained us handsomely in his solitary little ocean house. He was a man of singular patience and intelligence, who, when our queries struck him, rang as clear as a bell in response. The light-house lamp a few feet distant shone full into my chamber, and made it bright as day, so I knew exactly how the Highland Light bore all that night, and I was in no danger of being wrecked... I thought as I lay there, half-awake and half-asleep, looking upward through the window at the lights above my head, how many sleepless eyes from far out on the ocean stream -- mariners of all nations spinning their yarns through the various watches of the night -- were directed toward my couch.

(You can read the entire chapter by clicking here.)

One of the duties of the keeper was to count the vessels passing the light. In one 11 day period in July 1853, Keeper Enoch Hamilton counted 1,200 craft passing his station. As many as 600 vessels were reportedly counted in one day in 1867.

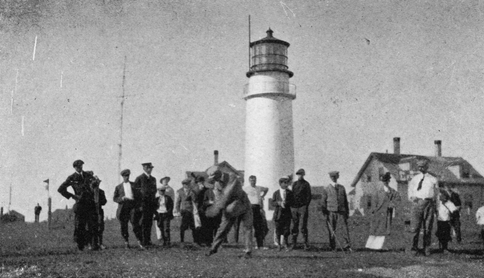

Highland Light c. 1890.

Storms often hit Highland Light with a vengeance. In the 19th century, keepers often had to stay in the lantern room all night to keep the glass clear. Other problems plagued the keepers in summer, such as swarms of moths and birds flying straight into the lantern glass.

An 1855 article in the Barnstable Patriot , written by a woman who spent time at the lighthouse, told of an incident in the 1833 keeper's house:

We were all seated cozily for dinner... when just as the hostess had put her fork into as plump a fowl as ever crowed, there came a rattle, a crash, smash and a cloud of dust which rendered all on the opposite side of the table invisible to me... I looked up and lo! The cause of the catastrophe! A part of the ceiling had fallen down over our devoted board and heads. It was not the first time the ceiling had acted so, I was told, as on a former occasion it had descended and Mrs. Small had patched the chasm with a newspaper.

The main keeper's dwelling was rebuilt soon after this incident, in 1856. A new brick tower was built in 1857 for $15,000, equipped with a first order Fresnel lens from Paris. This powerful light made Highland Light, the highest on the New England mainland, one of the coast's most powerful lights. Highland Light was for many years the first glimpse of America seen by many immigrants from Europe.

Further testifying to its importance, the new lighthouse was assigned a keeper and two assistants. The station also received a coal-burning Daboll fog signal, powerful enough to cut through the frequent thick fog.

An 1855 article in the Barnstable Patriot , written by a woman who spent time at the lighthouse, told of an incident in the 1833 keeper's house:

We were all seated cozily for dinner... when just as the hostess had put her fork into as plump a fowl as ever crowed, there came a rattle, a crash, smash and a cloud of dust which rendered all on the opposite side of the table invisible to me... I looked up and lo! The cause of the catastrophe! A part of the ceiling had fallen down over our devoted board and heads. It was not the first time the ceiling had acted so, I was told, as on a former occasion it had descended and Mrs. Small had patched the chasm with a newspaper.

The main keeper's dwelling was rebuilt soon after this incident, in 1856. A new brick tower was built in 1857 for $15,000, equipped with a first order Fresnel lens from Paris. This powerful light made Highland Light, the highest on the New England mainland, one of the coast's most powerful lights. Highland Light was for many years the first glimpse of America seen by many immigrants from Europe.

Further testifying to its importance, the new lighthouse was assigned a keeper and two assistants. The station also received a coal-burning Daboll fog signal, powerful enough to cut through the frequent thick fog.

Isaac M. Small, whose grandfather was the first keeper and owned the land the first lighthouse was built on, wrote a booklet in 1891 called Highland Light: This Book Tells You All About It.

Highland Golf Links, founded in 1892, is the oldest golf course on Cape Cod.

Small wrote about the daily life of the keepers:

The lives of the keepers are somewhat monotonous, though relieved in a measure during the summer months by visits of many pilgrims to this attractive Mecca.

The routine of their duties is regular and systematic. Promptly, one half hour before sunset the keeper whose watch it may be at the time repairs to the tower and makes preperations for the lighting of the lamps. At the moment the sun drops below the western horizon the light flashes out over the sea; the little cog wheels begin their revolutions; the tiny pumps force the oil up to the wicks and the night watch has begun. At 8 o'clock the man who has lighted the lamp is relieved by No. 2, who in turn is also relieved at midnight by No. 3, No. 1 again returning to duty at 4 a.m. As the sun shows its first gleam above the edge of the eastern sea the machinery is stopped and the light is allowed to gradually consume the oil remaining in the wicks and go out. This occurs in about fifteen minutes. As night comes on again No. 2 is the man to light the lamp, the watches are changed at 8, 12 and 4, and so go on as before night after night.

The lives of the keepers are somewhat monotonous, though relieved in a measure during the summer months by visits of many pilgrims to this attractive Mecca.

The routine of their duties is regular and systematic. Promptly, one half hour before sunset the keeper whose watch it may be at the time repairs to the tower and makes preperations for the lighting of the lamps. At the moment the sun drops below the western horizon the light flashes out over the sea; the little cog wheels begin their revolutions; the tiny pumps force the oil up to the wicks and the night watch has begun. At 8 o'clock the man who has lighted the lamp is relieved by No. 2, who in turn is also relieved at midnight by No. 3, No. 1 again returning to duty at 4 a.m. As the sun shows its first gleam above the edge of the eastern sea the machinery is stopped and the light is allowed to gradually consume the oil remaining in the wicks and go out. This occurs in about fifteen minutes. As night comes on again No. 2 is the man to light the lamp, the watches are changed at 8, 12 and 4, and so go on as before night after night.

Small also made a plea on behalf of the keepers:

A crowd gathers to watch a baseball game at Highland Light in the early 1900s

It is written somewhere that keepers must not accept tips from people who visit the light, but of course it does not really mean that, but should be understood that keepers should not solicit tips. When you have climbed to the top floor of that winding stair, and then have reached the ground again, and you are pretty nearly out of breath and exclaim, "My, but that was some climb," you would appreciate the feelings and condition of the keeper who had gone up and down some twenty times during the day. No law requires them to do this, but out of courtesy and your enjoyment they make the trips. Think it over and decide whether you would like to change places with them.

One of the worst storms in New England history struck on November 26, 1898. The storm was later dubbed the Portland Gale after the steamer Portland, lost with nearly 200 passengers in Massachusetts Bay.

At about 10 p.m. on the night of the storm the wind indicator at Highland Light was demolished with wind speeds reaching over 100 miles per hour. A short time later the windows in the lantern were blown out and the light went out. The storm lasted 36 hours, and gradually wreckage from the Portland washed up along Cape Cod's back shore.

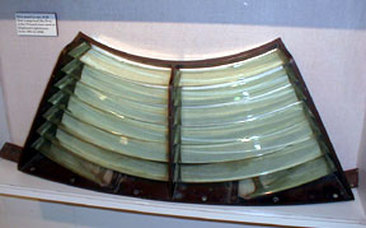

Left: A temporary light was used while the first order lens was installed in 1901.

An even larger Fresnel lens, floating on a bed of mercury, was installed in 1901. After an electric light was put inside this lens in 1932, the light became the coast's most powerful.

The 4,000,000 candlepower light could be seen for 45 miles, and reportedly as far as 75 miles in clear weather.

A Naval radio station was located at Highland Light in 1904. The station assumed great importance during World War I and was guarded by a detachment of Marines.

Left: A temporary light was used while the first order lens was installed in 1901.

An even larger Fresnel lens, floating on a bed of mercury, was installed in 1901. After an electric light was put inside this lens in 1932, the light became the coast's most powerful.

The 4,000,000 candlepower light could be seen for 45 miles, and reportedly as far as 75 miles in clear weather.

A Naval radio station was located at Highland Light in 1904. The station assumed great importance during World War I and was guarded by a detachment of Marines.

The giant Fresnel lens was removed in the early 1950s, replaced by a modern aerobeacon.

When the Fresnel lens was removed, it was destroyed. A fragment is on display in the museum at the lighthouse (right).

In 1961, the Coast Guard destroyed the assistant keeper's house and replaced it with a new duplex. The station was automated and destaffed in 1986. One of the last Coast Guard keepers was Patrick Punty, who lived at the station with his wife Katherine and two small children. Patrick and Katherine both felt they heard the voice of a ghostly woman in the keeper's house, according to an article in the New York Times. Patrick said, "If I was going to be a ghost, I'd like it to be in a lighthouse. I'd stay here the rest of my life."

After automation, the station's radio beacon remained in service and the keeper's dwelling continued to be used as Coast Guard housing.

There has been debate over the years about whether or not Highland Light was ever moved in the 19th century. Isaac M. Small stated in his booklet, "The present tower stands upon the EXACT SPOT WHERE THE ORIGINAL TOWER STOOD, IT WAS NEVER MOVED OR THE LOCATION CHANGED." Case closed.

In 1961, the Coast Guard destroyed the assistant keeper's house and replaced it with a new duplex. The station was automated and destaffed in 1986. One of the last Coast Guard keepers was Patrick Punty, who lived at the station with his wife Katherine and two small children. Patrick and Katherine both felt they heard the voice of a ghostly woman in the keeper's house, according to an article in the New York Times. Patrick said, "If I was going to be a ghost, I'd like it to be in a lighthouse. I'd stay here the rest of my life."

After automation, the station's radio beacon remained in service and the keeper's dwelling continued to be used as Coast Guard housing.

There has been debate over the years about whether or not Highland Light was ever moved in the 19th century. Isaac M. Small stated in his booklet, "The present tower stands upon the EXACT SPOT WHERE THE ORIGINAL TOWER STOOD, IT WAS NEVER MOVED OR THE LOCATION CHANGED." Case closed.

When the first lighthouse was built in 1797, it was over 500 feet from the edge of the 125 foot cliff.

The cliff continued to erode at a rate of at least three feet a year until, by the early 1990s, the present lighthouse stood just over a hundred feet from the edge. In 1990 alone 40 feet were lost just north of the lighthouse.

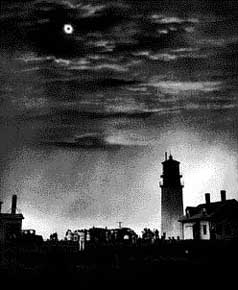

Left: A total eclipse of the sun seen from Highland Light on September 1, 1932.

A group within the Truro Historical Society began raising funds for the moving of Highland Light. Gordon Russell, president of both the Truro Historical Society and the Save the Light Committee, said that he and other volunteers sent out 30,000 brochures and collected 140,000 signatures on a petition. Local residents and tourists made donations and bought t-shirts and other souvenirs, and the society raised over $150,000.

Left: A total eclipse of the sun seen from Highland Light on September 1, 1932.

A group within the Truro Historical Society began raising funds for the moving of Highland Light. Gordon Russell, president of both the Truro Historical Society and the Save the Light Committee, said that he and other volunteers sent out 30,000 brochures and collected 140,000 signatures on a petition. Local residents and tourists made donations and bought t-shirts and other souvenirs, and the society raised over $150,000.

In 1996, this money was combined with $1 million in federal funds and $500,000 in state funds to pay for the move of the 404-ton lighthouse to a site 450 feet back from its former location.

View of the bluff and lighthouse in the late 1800s

The operation got underway in June 1996, under the direction of International Chimney Corp. of Buffalo, with the help of subcontractor Expert House Moving of Maryland, the same companies responsible for the successful move of Rhode Island's Block Island Southeast Light in 1993. Thousands of sightseers gathered to catch a glimpse of the rare move.

The foundation of the lighthouse was excavated and four levels of criss-crossing beams were inserted beneath the tower. The entire structure was lifted with hydraulic jacks and mounted on rollers, then set on rails. The move took 18 days.

The foundation of the lighthouse was excavated and four levels of criss-crossing beams were inserted beneath the tower. The entire structure was lifted with hydraulic jacks and mounted on rollers, then set on rails. The move took 18 days.

It appeared to go smoothly, but consultant Peter Friesen said, "The other one behaved better than this one," referring to Block Island Southeast Light.

During the move workers placed quarters on the beams. The coins, flattened by the lighthouse, were later auctioned off for as high as $57, with the money going to the Truro Historical Society.

The relocated lighthouse stands close to the seventh fairway of the Highland Golf Links, prompting some to declare it the world's first life-sized miniature golf course. "We'll get a windmill from Eastham and put it on number one," joked the club's greenskeeper.

After an errant golf ball broke a pane in the lantern room, new unbreakable panes were installed.

The relocated lighthouse stands close to the seventh fairway of the Highland Golf Links, prompting some to declare it the world's first life-sized miniature golf course. "We'll get a windmill from Eastham and put it on number one," joked the club's greenskeeper.

After an errant golf ball broke a pane in the lantern room, new unbreakable panes were installed.

On Sunday, November 3, 1996 Highland Light was relighted in its new location. Over 200 people toured the tower's interior before the relighting ceremony.

The Highland Light Bagpipe Band performed in full regalia, and Congressman Gerry Studds, an important proponent of the move, spoke to the assembled crowd.

"While this light may not save lives," said Studds, "it will inspire lives for a long time to come."

In the summer of 1998 Highland Light was opened for visitors, with volunteers giving tours. There is a small gift shop, along with exhibits, in the keepers' house.

"While this light may not save lives," said Studds, "it will inspire lives for a long time to come."

In the summer of 1998 Highland Light was opened for visitors, with volunteers giving tours. There is a small gift shop, along with exhibits, in the keepers' house.

In April 2001 the lighthouse got a needed facelift.

The job performed by Campbell Construction of Beverly, Massachusetts entailed sandblasting the lead paint from the interior of the lantern room and the tower's stairs, removing rust from the exterior iron work and replacing some railing sections as well as rusted iron panels. Some cracks in the iron work were welded with certanium.

A new window was installed, and some of the brick work on the ocean-facing side of the tower had to be replaced. The interior of the lantern room and the stairs were repainted, as was the entire exterior of the tower.

In addition, a new ventilation system was installed, making visits to the lantern room more comfortable in summer.

Left: During the April 2001 restoration.

Below: Two interior views of the tower.

A new window was installed, and some of the brick work on the ocean-facing side of the tower had to be replaced. The interior of the lantern room and the stairs were repainted, as was the entire exterior of the tower.

In addition, a new ventilation system was installed, making visits to the lantern room more comfortable in summer.

Left: During the April 2001 restoration.

Below: Two interior views of the tower.

Highland Light is easy to drive to, but keep in mind that the signs say "Cape Cod Light." This became the official name in 1976, but to most New Englanders it's always been Highland Light.

In 2014 the license to manage the property went to Eastern National. Click here for more information.

In September 2018 Cape Cod National Seashore Superintendent Brian Carlstrom announced that the lighthouse would undergo an extensive rehabilitation beginning in late fall 2018. The lighthouse will be closed for the 2019 season.

In 2014 the license to manage the property went to Eastern National. Click here for more information.

In September 2018 Cape Cod National Seashore Superintendent Brian Carlstrom announced that the lighthouse would undergo an extensive rehabilitation beginning in late fall 2018. The lighthouse will be closed for the 2019 season.

|

|

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Isaac Small (1797-1812), Constant Hopkins (1812-1817), John Grocier (or Grozier) (1817-c.1840), Jesse Holbrook (1840-1843), James Small (1843-1849 and 1853-1856), Warren Newcomb (1849-1850), Enoch Hamilton (1850-c.1853), Horace A. Hughes (1856-1859), John Kenney (1859-1861), Thomas R. Small (1861-1866), Hezekiah P Hughes (1866-1870), Thomas Lowe (1870-1872), William W. Goss (1872-1873), David F Loring (1873-1887), Amasa S Dyer (1887-1891), Stephen Rich (1891-1912), George A. Faulkner (1912-1915), Fred W. Tibbetts (1915-1935), William A. Joseph (1935-1947)

First Assistants: James Small (1857-1859), T. R. Small (1859), Hugh Hopkins (1859-1861), Samuel Knowles (1861-1862), Henry Hutchings (1862-1865), John P. Grozier (1865-1867), Thomas Lowe (1868-1870), Peter Higgins (1870-1871), Samuel T. Eastman (1871-1873), David F. Loring (1873), Thomas R. Small (1873-1874), John Francis (1874-1875), Stephen S. Lewis (1875-1883), George Dolby (1883-1885, Philip R. Smith (1883-1886), Amasa S. Dyer (1886-1887), Frank Chapman (1887-1890), Thomas Ellis (1890-1891), Stephen D. Rich (1891), Michael J. Curran (1891 ), Edwin F. King (1891-1892), John B Carter (1892-1894), .Albert M Horte (1894 ), Russell B. Eastman (1900-1906), John R. Forrest (1906-1907), George A. Faulkner (1908-1912), Joseph Cabral (1912), Fred W. Tibbetts (1912-1915), ? Cobb (1917-1923), George C. Smith (1923-1925), ? McAfee (1925-1926), William A. Joseph (c. 1923-1935), ? Howard (1935-? ), Charles F. Ellis (c. 1938-1946)

Second Assistants: Thomas H Kenny (1857-1861), E. S. Harding (1861-1864), John C. Doane (1864-1865), Nath. P. Atwood (1865-1868), Jeremiah T. Stevens (1871-1872), George Allen (1872-1873), David F. Loring (1873), Thomas R. Small (1873), John Francis (1874), Stephen S. Lewis (1874-1875), E. Mayo (1875-1876), Thomas E Marchant (1876-1880), Cullen A Hughes (1880-1882), George W Crosby (1882), George Dolby (1882-1883), Philip R Smith (1883-1885), Amasa S. Dyer (1885-1886), John R. Smith (1886-1887), Thomas Ellis (1887-1890), Stephen D. Rich (1890-1891), William Merchant (1891), Edwin King Jr. (1891), John B. Carter (1891-1892), James Kingsley (1892-1893), John D. Snow (1893-1896), Russell B. Easman (1896-1900), Frank Lowe (1900), Oscar C.G. Bohm (1902), Ernest Small (1903-1905), John R Forrest (1905-1906), George A. Faulkner (1906-1908), J. L. Cabral (1908-1911), John Hansen (1912), F. W. Tibbett (1912), W. E. Wheeler (1912-1913), Horace Hamilton (1913-1914), ? Cobb (1914-1916), James Yates (1916-1917), ? Cochrane (1917-1920), G. C. Smith (1920-1923), William A Joseph (c. 1921-1923), Carl Delano Hill (1932-1934), C. F. Ellis (1934-?), Anthony K. Souza (c. 1938-1939),William C. Dawe (1939-1942), Harvey C. Harris (1942), John Botello (c. 1942-1944)

U.S. Coast Guard Officer in Charge: Alfred Viera (c. 1951-1953), Donald Ormsby (1953-1956), William E. Joseph (1957-1959), Elias J. Martinez (1959-1965), William J. McEachern (1965-?), George Bassett Jr. (1967-1968), Robert E. Holbert (1968-c.1970), A. G. "Sandy" Lyle (1978-1982), Lenny Sendzia (1982-1984); Jeffrey A. Kahler (May 1984 - June 1986)

Others: Raymond Rich (substitute keeper c. 1904), Vilas Keckley (radio operator, c. early 1930s), Thornquist (Coast Guard, c. 1940s), Bernie Webber (Coast Guard, 1946-?), Charles Johnson (Coast Guard c. 1976), Chris Ordway (Coast Guard c, 1982), Patrick Prunty (Coast Guard, c.1984-1986)

In April 2009, I received an email from Jeffrey A. Kahler, Master Chief Boatswain's Mate, USCG (retired) -- the last keeper of this light station. He wrote, "I thoroughly enjoyed my experience as a keeper of the Highland Lighthouse and am proud to be part of her history. My family and I have fond memories of life at the lighthouse."

Isaac Small (1797-1812), Constant Hopkins (1812-1817), John Grocier (or Grozier) (1817-c.1840), Jesse Holbrook (1840-1843), James Small (1843-1849 and 1853-1856), Warren Newcomb (1849-1850), Enoch Hamilton (1850-c.1853), Horace A. Hughes (1856-1859), John Kenney (1859-1861), Thomas R. Small (1861-1866), Hezekiah P Hughes (1866-1870), Thomas Lowe (1870-1872), William W. Goss (1872-1873), David F Loring (1873-1887), Amasa S Dyer (1887-1891), Stephen Rich (1891-1912), George A. Faulkner (1912-1915), Fred W. Tibbetts (1915-1935), William A. Joseph (1935-1947)

First Assistants: James Small (1857-1859), T. R. Small (1859), Hugh Hopkins (1859-1861), Samuel Knowles (1861-1862), Henry Hutchings (1862-1865), John P. Grozier (1865-1867), Thomas Lowe (1868-1870), Peter Higgins (1870-1871), Samuel T. Eastman (1871-1873), David F. Loring (1873), Thomas R. Small (1873-1874), John Francis (1874-1875), Stephen S. Lewis (1875-1883), George Dolby (1883-1885, Philip R. Smith (1883-1886), Amasa S. Dyer (1886-1887), Frank Chapman (1887-1890), Thomas Ellis (1890-1891), Stephen D. Rich (1891), Michael J. Curran (1891 ), Edwin F. King (1891-1892), John B Carter (1892-1894), .Albert M Horte (1894 ), Russell B. Eastman (1900-1906), John R. Forrest (1906-1907), George A. Faulkner (1908-1912), Joseph Cabral (1912), Fred W. Tibbetts (1912-1915), ? Cobb (1917-1923), George C. Smith (1923-1925), ? McAfee (1925-1926), William A. Joseph (c. 1923-1935), ? Howard (1935-? ), Charles F. Ellis (c. 1938-1946)

Second Assistants: Thomas H Kenny (1857-1861), E. S. Harding (1861-1864), John C. Doane (1864-1865), Nath. P. Atwood (1865-1868), Jeremiah T. Stevens (1871-1872), George Allen (1872-1873), David F. Loring (1873), Thomas R. Small (1873), John Francis (1874), Stephen S. Lewis (1874-1875), E. Mayo (1875-1876), Thomas E Marchant (1876-1880), Cullen A Hughes (1880-1882), George W Crosby (1882), George Dolby (1882-1883), Philip R Smith (1883-1885), Amasa S. Dyer (1885-1886), John R. Smith (1886-1887), Thomas Ellis (1887-1890), Stephen D. Rich (1890-1891), William Merchant (1891), Edwin King Jr. (1891), John B. Carter (1891-1892), James Kingsley (1892-1893), John D. Snow (1893-1896), Russell B. Easman (1896-1900), Frank Lowe (1900), Oscar C.G. Bohm (1902), Ernest Small (1903-1905), John R Forrest (1905-1906), George A. Faulkner (1906-1908), J. L. Cabral (1908-1911), John Hansen (1912), F. W. Tibbett (1912), W. E. Wheeler (1912-1913), Horace Hamilton (1913-1914), ? Cobb (1914-1916), James Yates (1916-1917), ? Cochrane (1917-1920), G. C. Smith (1920-1923), William A Joseph (c. 1921-1923), Carl Delano Hill (1932-1934), C. F. Ellis (1934-?), Anthony K. Souza (c. 1938-1939),William C. Dawe (1939-1942), Harvey C. Harris (1942), John Botello (c. 1942-1944)

U.S. Coast Guard Officer in Charge: Alfred Viera (c. 1951-1953), Donald Ormsby (1953-1956), William E. Joseph (1957-1959), Elias J. Martinez (1959-1965), William J. McEachern (1965-?), George Bassett Jr. (1967-1968), Robert E. Holbert (1968-c.1970), A. G. "Sandy" Lyle (1978-1982), Lenny Sendzia (1982-1984); Jeffrey A. Kahler (May 1984 - June 1986)

Others: Raymond Rich (substitute keeper c. 1904), Vilas Keckley (radio operator, c. early 1930s), Thornquist (Coast Guard, c. 1940s), Bernie Webber (Coast Guard, 1946-?), Charles Johnson (Coast Guard c. 1976), Chris Ordway (Coast Guard c, 1982), Patrick Prunty (Coast Guard, c.1984-1986)

In April 2009, I received an email from Jeffrey A. Kahler, Master Chief Boatswain's Mate, USCG (retired) -- the last keeper of this light station. He wrote, "I thoroughly enjoyed my experience as a keeper of the Highland Lighthouse and am proud to be part of her history. My family and I have fond memories of life at the lighthouse."