History of Hendricks Head Light, West Southport, Maine

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Click here for a gallery of Hendricks Head Light photos on SmugMug (prints and gift items available)

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

The light burns bright. All well at the Head. -- Log entry by Keeper Jaruel Marr.

Circa 1859. National Archives.

Hendricks Head Light was established on the east side of the entrance to the Sheepscot River in 1829, near the part of Southport Island now known as Cozy Harbor and six miles from Boothbay Harbor.

The first lighthouse was a granite keeper's dwelling with the tower on its roof. It exhibited a fixed white light 39 feet above the water.

The original fixed white light was changed to a revolving light in July 1855.

The first lighthouse was a granite keeper's dwelling with the tower on its roof. It exhibited a fixed white light 39 feet above the water.

The original fixed white light was changed to a revolving light in July 1855.

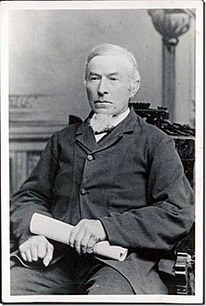

Jaruel Marr, who was born the same year the original lighthouse was built, became keeper in 1866, after returning from the Civil War.

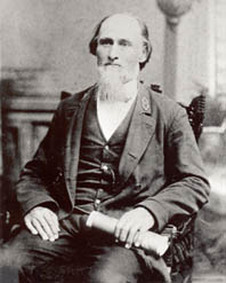

Right: Ephraim Pinkham was keeper 1859-61. His son, Merritt Parker Pinkham, married Mary Catherine Marr, daughter of Keeper Jaruel Marr. Courtesy of Glenda Mitchell.

Marr's great-grandson Merle Bogues described Marr's Civil War service in his self-published Flivers and Long Dorys:

He and several other young Southport men walked the 60 miles to Portland and enlisted in the 7th Maine, Company D of the Union Army, leaving my great grandmother and three small children behind.

Some months later, while lying wounded and incarcerated in the Confederate Army's Liberty Prison at Richmond, Virginia, he was nursed back to health by a Union Army Doctor, also a prisoner, named Wolcott. My grandfather [Jaruel's son] was named in Dr. Wolcott's honor.

According to Bogues, Jaruel Marr was appointed keeper at Hendricks Head as "token compensation" for the wounds he suffered in the war. Jaruel Marr served as keeper until 1895, when he retired.

The logs he kept reflect Marr 's devotion to the lighthouse.

Jaruel Marr, courtesy of Elisa Trepanier

He often made several trips to the lantern room during the night to check the light. For instance:

Trimmed the wick at half past 12, at half past 4 the light was dim so I raised the wick a sixteenth of an inch to make all right again. The oil carbonizes the wick and causes it to become crusty in about 8 hours.

Jaruel Marr's logs also convey the power of storms at Hendricks Head. He recorded that one gale moved a huge boulder, 8 by 12 feet, 21 feet from its original resting place.

Historian Edward Rowe Snow, in his book Famous Lighthouses of New England, related a well-known story of Hendricks Head Light. The tale concerned a vessel wrecked near Hendricks Head in a March gale sometime around 1870 (1875, according to a 1955 newspaper story).

According to Snow, the keeper and his wife could see those on board the wrecked ship hanging to the rigging, practically frozen to death. The high wind and rough seas made it impossible for the keeper to launch a dory. As evening arrived the helpless keeper saw a strange bundle floating toward the shore.

Trimmed the wick at half past 12, at half past 4 the light was dim so I raised the wick a sixteenth of an inch to make all right again. The oil carbonizes the wick and causes it to become crusty in about 8 hours.

Jaruel Marr's logs also convey the power of storms at Hendricks Head. He recorded that one gale moved a huge boulder, 8 by 12 feet, 21 feet from its original resting place.

Historian Edward Rowe Snow, in his book Famous Lighthouses of New England, related a well-known story of Hendricks Head Light. The tale concerned a vessel wrecked near Hendricks Head in a March gale sometime around 1870 (1875, according to a 1955 newspaper story).

According to Snow, the keeper and his wife could see those on board the wrecked ship hanging to the rigging, practically frozen to death. The high wind and rough seas made it impossible for the keeper to launch a dory. As evening arrived the helpless keeper saw a strange bundle floating toward the shore.

The keeper snatched the bundle from the waves with a boat hook and discovered that it was actually two featherbeds tied together. He cut apart the ropes and discovered a box between the beds.

Opening the box, the keeper discovered a tiny baby girl, crying and very much alive. The box also contained a note from the baby's mother, commending the girl's soul to God.

The keeper and his wife immediately took the baby to the warmth of their kitchen. After seeing that the baby was in good health, the keeper went outside and saw that the vessel had vanished beneath the waves. Wreckage was soon washing ashore. The keeper and his wife adopted the baby girl and raised her at the lighthouse, according to the story as it usually told.

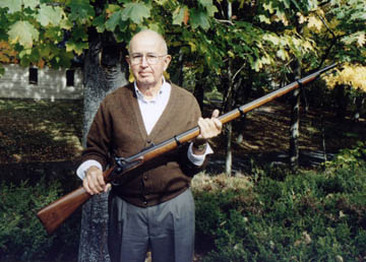

Right: Robert L. Marr of Kittery, Maine, is seen here holding a rifle that it is believed to have been issued to his great grandfather, Jaruel Marr, on his release from a Confederate prison during the Civil War. Released prisoners were routinely issued rifles to enable them to hunt for food during the long walk home.

The keeper and his wife immediately took the baby to the warmth of their kitchen. After seeing that the baby was in good health, the keeper went outside and saw that the vessel had vanished beneath the waves. Wreckage was soon washing ashore. The keeper and his wife adopted the baby girl and raised her at the lighthouse, according to the story as it usually told.

Right: Robert L. Marr of Kittery, Maine, is seen here holding a rifle that it is believed to have been issued to his great grandfather, Jaruel Marr, on his release from a Confederate prison during the Civil War. Released prisoners were routinely issued rifles to enable them to hunt for food during the long walk home.

Some local historians question whether the events ever took place, and no such incident was ever reported by the local newspaper. Barbara Rumsey of the Boothbay Region Historical Society theorized that the story may have originated with a 1900 novel called Uncle Terry, which told a very similar story.

Wolcott Marr, courtesy of Robert Marr

But according to some of the descendants of Jaruel and Wolcott Marr, the story is true. Elisa Trepanier, Jaruel Marr's great-great granddaughter, says, "I know the story of the baby girl in the mattress to be true as told to us by Jaruel's children and grandchildren. The baby girl was adopted by a doctor and his wife who were summer residents, as Jaruel and Catherine had too many children of their own to care for. I remember the baby girl was named Seaborn."

The debate over the veracity of the "Hendricks Head Baby" story may never be settled, but it is one of New England's most enduring lighthouse stories. It also inspired a children's book, Toni Buzzeo's The Sea Chest, and a novel, Waterbaby by Cris Mazza. A similar story is told in the recent best selling novel The Light Between Oceans by M. L. Stedman.

The present 39-foot square brick tower replaced the first lighthouse in 1875. On September 23, 1875, the fourth-order lens was transferred from the old tower to the new one.Jaruel Marr recorded that the family moved into their new home on September 30 of that year, extremely happy with their new cook stove. A covered walkway connected the lighthouse to the keeper's house.

A pyramidal skeleton-type bell tower was added in 1891 and an oil house was built in 1895. For several years before the bell tower was built, a small hand-operated bell was in place.

The debate over the veracity of the "Hendricks Head Baby" story may never be settled, but it is one of New England's most enduring lighthouse stories. It also inspired a children's book, Toni Buzzeo's The Sea Chest, and a novel, Waterbaby by Cris Mazza. A similar story is told in the recent best selling novel The Light Between Oceans by M. L. Stedman.

The present 39-foot square brick tower replaced the first lighthouse in 1875. On September 23, 1875, the fourth-order lens was transferred from the old tower to the new one.Jaruel Marr recorded that the family moved into their new home on September 30 of that year, extremely happy with their new cook stove. A covered walkway connected the lighthouse to the keeper's house.

A pyramidal skeleton-type bell tower was added in 1891 and an oil house was built in 1895. For several years before the bell tower was built, a small hand-operated bell was in place.

Jaruel Marr and his wife Catherine had five children, and all three of their sons became Maine lighthouse keepers.

Wolcott Marr with one of his 10 children. Courtesy of Elisa Trepanier.

Two sons, Clarence and Preston, became keepers at Pemaquid Point Light and Portland Breakwater Light respectively. Their son Wolcott Marr entered the Lighthouse Service in 1890 and first served as an assistant at the Cape Elizabeth Two Lights, then at the Cuckolds Fog Signal Station. His next station was his childhood home.

On July 1, 1895 Wolcott Marr wrote in the log at Hendricks Head, "Arrived at this station at 2 PM to relieve Mr. Jaruel Marr, who has been keeper here for the past 29 years." Wolcott Marr and his wife Hattie (Hatch) had three children when they moved to Hendricks Head, and six more would be born during their stay at the lighthouse.

Merle Bouges provides more details of the life of Keeper Wolcott Marr and his family at the lighthouse:

Through the years Grampa Marr had hauled enough dirt to plant a lawn and flower garden around the main buildings. A few hundred feet back from the shore was a large garden and a small pasture where he farmed on a small scale and kept a cow to augment the diets of a large family.

The Lighthouse Keeper was responsible for all maintenance of buildings, grounds and equipment, as well as very frequent inspections of the lamp during the night and times of foul weather. My grandfather also found time to fish, lobster, dig for clams, garden and take summer visitors for boat rides around the nearby islands. In addition, in winter months he fashioned fine pieces of furniture, utensils, and tools This was permissible as long as someone was on duty at the light. If needed, he could be summoned by my grandmother or uncles by ringing the bell, which could be heard for miles.

But lighthouse life was not always routine and tedious. Despite the light and bell, one stormy night in the winter of 1914 a 140-foot three-masted schooner went aground at the end of Hendrick's Head Point with a cargo of lumber and a crew of 15 aboard. Grampa Marr was astonished that night to see the masts of the ship through the blowing snow almost right before his eyes as he stood in the lighthouse tower during one of his inspection tours. He could see most of the sailors hanging from the rigging where they had climbed to escape the 20-foot breakers crashing over the deck. Grampa ran down the circular stairway, grabbing a coil of rope on the way, and continued to the end of the point, shouting to his older sons to come and help as he went through the house. He heaved the coil aboard the schooner and the crew rigged a bosun's chair and were hauled ashore by Grampa and my uncles. My grandmother made sandwiches and hot coffee for the cold, wet and miserable crew who sat up the rest of the night in the downstairs rooms of the lighthouse.

Grampa Marr was tall, slender and wore a small blonde mustache He looked very impressive to me in his navy blue lighthouse keeper uniform with its brass buttons and uniform type cap, but he seldom wore it. He disliked the uniform and only wore it when he expected the lighthouse tender. When the tender whistle would blow, Grampa would run for the house, don his uniform and look like a million when the inspectors arrived. Otherwise he dressed in normal civilian attire.

On July 1, 1895 Wolcott Marr wrote in the log at Hendricks Head, "Arrived at this station at 2 PM to relieve Mr. Jaruel Marr, who has been keeper here for the past 29 years." Wolcott Marr and his wife Hattie (Hatch) had three children when they moved to Hendricks Head, and six more would be born during their stay at the lighthouse.

Merle Bouges provides more details of the life of Keeper Wolcott Marr and his family at the lighthouse:

Through the years Grampa Marr had hauled enough dirt to plant a lawn and flower garden around the main buildings. A few hundred feet back from the shore was a large garden and a small pasture where he farmed on a small scale and kept a cow to augment the diets of a large family.

The Lighthouse Keeper was responsible for all maintenance of buildings, grounds and equipment, as well as very frequent inspections of the lamp during the night and times of foul weather. My grandfather also found time to fish, lobster, dig for clams, garden and take summer visitors for boat rides around the nearby islands. In addition, in winter months he fashioned fine pieces of furniture, utensils, and tools This was permissible as long as someone was on duty at the light. If needed, he could be summoned by my grandmother or uncles by ringing the bell, which could be heard for miles.

But lighthouse life was not always routine and tedious. Despite the light and bell, one stormy night in the winter of 1914 a 140-foot three-masted schooner went aground at the end of Hendrick's Head Point with a cargo of lumber and a crew of 15 aboard. Grampa Marr was astonished that night to see the masts of the ship through the blowing snow almost right before his eyes as he stood in the lighthouse tower during one of his inspection tours. He could see most of the sailors hanging from the rigging where they had climbed to escape the 20-foot breakers crashing over the deck. Grampa ran down the circular stairway, grabbing a coil of rope on the way, and continued to the end of the point, shouting to his older sons to come and help as he went through the house. He heaved the coil aboard the schooner and the crew rigged a bosun's chair and were hauled ashore by Grampa and my uncles. My grandmother made sandwiches and hot coffee for the cold, wet and miserable crew who sat up the rest of the night in the downstairs rooms of the lighthouse.

Grampa Marr was tall, slender and wore a small blonde mustache He looked very impressive to me in his navy blue lighthouse keeper uniform with its brass buttons and uniform type cap, but he seldom wore it. He disliked the uniform and only wore it when he expected the lighthouse tender. When the tender whistle would blow, Grampa would run for the house, don his uniform and look like a million when the inspectors arrived. Otherwise he dressed in normal civilian attire.

Wolcott Marr remained keeper at Hendricks Head until his death in 1930. Bogues wrote that his grandfather had "invested in the stock market but lost most of it in the crash of 1929. He died from a case of acute bleeding stomach ulcers at the age of 61."

U.S. Coast Guard photo

According to some sources, Wolcott Marr had an unusual distinction: he was born, married, and died in the same room at Hendricks Head Light.

The light was converted to automatic operation utilizing acetylene gas in 1933, and the fog bell was discontinued. The light was soon replaced by an offshore buoy. According to Sidney Baldwin's Casting Off from Boothbay Harbor:

The men who depended on these waters for their livelihood complained loudly. No flashing light buoy could take the place of their land light! But they lost their case, and the light was sold.

The light station and the entire peninsula were sold in 1934 to Dr. William P. Browne of Connecticut. Until then, the house had no electricity or plumbing.

The light was converted to automatic operation utilizing acetylene gas in 1933, and the fog bell was discontinued. The light was soon replaced by an offshore buoy. According to Sidney Baldwin's Casting Off from Boothbay Harbor:

The men who depended on these waters for their livelihood complained loudly. No flashing light buoy could take the place of their land light! But they lost their case, and the light was sold.

The light station and the entire peninsula were sold in 1934 to Dr. William P. Browne of Connecticut. Until then, the house had no electricity or plumbing.

After electricity came to the house in 1951 the Coast Guard decided to reactivate the light, since boating traffic in the area had increased.

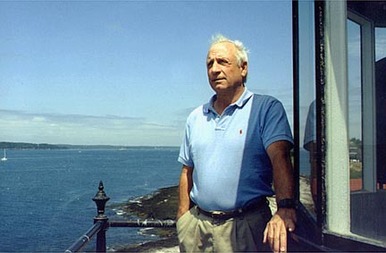

Ben Russell

A ferocious storm on January 9, 1978, demolished the boathouse and also destroyed the walkway that had connected the lighthouse to the fog bell tower.

In 1979, the fifth-order Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern 250 mm optic.

Dr. Browne's daughter Mary Charbonneau and her husband Gil owned the lighthouse property for many years. Mr. Charbonneau received national attention for constructing miniature ships-in-bottles.

In 1991, Benjamin and Luanne Russell of Alabama bought the 4 1/2-acre lighthouse property, and they subsequently restored all of the structures. The buildings survive in beautiful condition and the fixed white light with red sectors continues as an active aid to navigation.

Hendricks Head Light can be seen from a small beach in West Southport. Closer views are available from excursion boats leaving Boothbay Harbor and Bath.

In 1979, the fifth-order Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern 250 mm optic.

Dr. Browne's daughter Mary Charbonneau and her husband Gil owned the lighthouse property for many years. Mr. Charbonneau received national attention for constructing miniature ships-in-bottles.

In 1991, Benjamin and Luanne Russell of Alabama bought the 4 1/2-acre lighthouse property, and they subsequently restored all of the structures. The buildings survive in beautiful condition and the fixed white light with red sectors continues as an active aid to navigation.

Hendricks Head Light can be seen from a small beach in West Southport. Closer views are available from excursion boats leaving Boothbay Harbor and Bath.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John Upham (1829-1837), Stephen Smith (1837-1841), Thomas Pierce (1841-1845), Joshua Berry (1845-1849), Thomas Pierce (1849-1853), Simeon Cromwell (1853-1857), William Orne (1857-1859), Ephraim Pinkham (1859-1861), John Stevens (1861-1866), Jaruel Marr (1866-1895), Wolcott Marr (1895-1930), Charles Knight (1930-1933).