History of West Chop Light, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

The harbor at Vineyard Haven was Martha's Vineyard's busiest in the nineteenth century, and it's still busy with ferry traffic today. The harbor is protected by two areas of land known as East Chop and West Chop. For many years, West Chop was mainly a sheep pasture until it grew into an exclusive summer resort in the late 1800s.

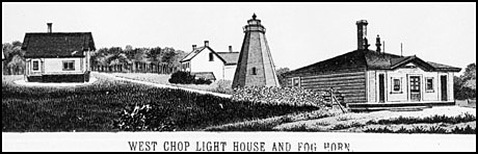

West Chop Light c. 1870s

The harbor and the village around it were long called Holmes Hole -- named for a settler from Plymouth, according to some sources, or stemming from an Indian word meaning old house or dwelling, according to others. The people of Holmes Hole were disappointed that the harbor at Edgartown got a lighthouse (at Cape Poge) in 1801, even though Holmes Hole's harbor was busier.

When another lighthouse was commissioned in 1817 at Tarpaulin Cove on Naushon Island, about a dozen miles to the west, the Holmes Holers were incredulous. The residents petitioned their congressman, John Reed, with success.

To aid vessels heading in and out of the harbor as well as coastal traffic passing through Vineyard Sound, Congress appropriated $5,000 on March 3, 1817. The first lighthouse at West Chop, a 25-foot rubblestone tower, was erected along with a stone dwelling, 20 by 34 feet. A fixed white light was exhibited from about 60 feet above the water. The light went into service on October 5, 1817. James Shaw West, a Tisbury native, became the first keeper at $350 per year.

When another lighthouse was commissioned in 1817 at Tarpaulin Cove on Naushon Island, about a dozen miles to the west, the Holmes Holers were incredulous. The residents petitioned their congressman, John Reed, with success.

To aid vessels heading in and out of the harbor as well as coastal traffic passing through Vineyard Sound, Congress appropriated $5,000 on March 3, 1817. The first lighthouse at West Chop, a 25-foot rubblestone tower, was erected along with a stone dwelling, 20 by 34 feet. A fixed white light was exhibited from about 60 feet above the water. The light went into service on October 5, 1817. James Shaw West, a Tisbury native, became the first keeper at $350 per year.

In 1838, Lt. Edward D. Carpender found the station in excellent order, "justifying the high reputation it enjoys along the coast." He also noted that erosion threatened the tower.

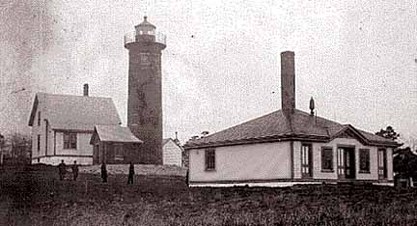

Circa 1890 illustration

Engineer I.W.P. Lewis recognized the importance of West Chop Light in 1843:

This light being placed at the Chops of the Vineyard sound, is exceedingly useful for all coasters bound east or west. It also affords an excellent mark for clearing various shoals, and indicates the position of Holmes's Hole anchorage. The present keeper deserves praise for the great neatness of the establishment.

James West , still keeper in 1843, reported that the tower and dwelling were both leaky. The inside of the tower was coated with ice in winter. West also complained that he was not allowed a boat, which prevented him "from rendering assistance to the many vessels that get ashore in this neighborhood." The keeper pointed out that the bluff on which the lighthouse stood had eroded to within 37 feet of the tower's base.

The station was rebuilt in 1846. A round stone tower and a stone Cape-style keeper's house were constructed about 1,000 feet southeast of the old location. The 1846 tower was later enclosed in shingled wooden sheathing, creating in an octagonal form. This was apparently done to cut down on leaks -- an 1850 inspection referred to the tower as "somewhat leaky."

This light being placed at the Chops of the Vineyard sound, is exceedingly useful for all coasters bound east or west. It also affords an excellent mark for clearing various shoals, and indicates the position of Holmes's Hole anchorage. The present keeper deserves praise for the great neatness of the establishment.

James West , still keeper in 1843, reported that the tower and dwelling were both leaky. The inside of the tower was coated with ice in winter. West also complained that he was not allowed a boat, which prevented him "from rendering assistance to the many vessels that get ashore in this neighborhood." The keeper pointed out that the bluff on which the lighthouse stood had eroded to within 37 feet of the tower's base.

The station was rebuilt in 1846. A round stone tower and a stone Cape-style keeper's house were constructed about 1,000 feet southeast of the old location. The 1846 tower was later enclosed in shingled wooden sheathing, creating in an octagonal form. This was apparently done to cut down on leaks -- an 1850 inspection referred to the tower as "somewhat leaky."

James West was still keeper when the new tower was completed. He resigned in 1847 and was succeeded by Charles West (not one of his sons). Charles West remained keeper until 1868, when his son -- also named Charles -- succeeded him.

Circa 1890. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow

The younger West remained at the station until 1909, ending a remarkable 62-year father-son dynasty.

For a time, beginning in 1857, there was an additional light shown from a lantern on the roof of the keeper's house; the Lighthouse Board explained that this light replaced a system of three range lights that served as a guide into the harbor.

According to historian Edward Rowe Snow, a schooner laden with bricks ran aground near the lighthouse in 1877. Tons of bricks were thrown overboard so the vessel could float, and the bricks could be seen for many decades at low tide.

For a time, beginning in 1857, there was an additional light shown from a lantern on the roof of the keeper's house; the Lighthouse Board explained that this light replaced a system of three range lights that served as a guide into the harbor.

According to historian Edward Rowe Snow, a schooner laden with bricks ran aground near the lighthouse in 1877. Tons of bricks were thrown overboard so the vessel could float, and the bricks could be seen for many decades at low tide.

A steam-driven fog signal housed in a new building was added in 1882, and the same year a one-and-a-half-story, wood-frame assistant keeper's house was built. The first assistant keeper was George Dolby, who later became the principal keeper (1909-19).

From A Trip to Cape Cod, 1898

In 1888, the stone dwelling built in 1846 was removed and a second wood-frame house was erected.

By the early 1890s, West Chop had become a summer resort and the proliferation of large houses in the area began to obscure the light. A 17-foot mast with the light on top was added to the tower, then the 1846 tower was replaced by a new 45-foot brick tower in 1891. The tower, originally red, was painted white in 1896.

Octave Ponsart, formerly at Dumpling Rock and Cuttyhunk lights, became keeper in 1946. As part of his duties, Ponsart also had to check periodically check on the automated lights at Edgartown, East Chop, and Cape Poge.

By the early 1890s, West Chop had become a summer resort and the proliferation of large houses in the area began to obscure the light. A 17-foot mast with the light on top was added to the tower, then the 1846 tower was replaced by a new 45-foot brick tower in 1891. The tower, originally red, was painted white in 1896.

Octave Ponsart, formerly at Dumpling Rock and Cuttyhunk lights, became keeper in 1946. As part of his duties, Ponsart also had to check periodically check on the automated lights at Edgartown, East Chop, and Cape Poge.

Ponsart's wife, Emma, was a regular contributor to a newspaper called the Maine Coast Fisherman, which ran a column of reports from light stations.

Left: Keeper Octave Ponsart, courtesy of Seamond Ponsart Roberts.

Here are excerpts from a letter from Emma Ponsart in November 1954:

Hurricane Carol took all the docks down at West Chop. . . . I was out to look at the surf during it and it came way up over our bank. We had no electricity for three days. Many yachts were driven on the land. Then, Hurricane Edna came along. What a mess I had to clean up around the place! It took our skiff into two yards down from us. Up to Menemsha Creek, it was a sight to see the fishing boats, yachts and fish buildings all wrecked. . .

My garden was ripped to pieces in the storm. It broke our birdhouses too. I have been raking leaves and tree limbs ever since the two storms. I don't feel so good. I got a cold since there was no heat in the place during the storms. Our government house is a good one though to have stood all it took.

Here are excerpts from a letter from Emma Ponsart in November 1954:

Hurricane Carol took all the docks down at West Chop. . . . I was out to look at the surf during it and it came way up over our bank. We had no electricity for three days. Many yachts were driven on the land. Then, Hurricane Edna came along. What a mess I had to clean up around the place! It took our skiff into two yards down from us. Up to Menemsha Creek, it was a sight to see the fishing boats, yachts and fish buildings all wrecked. . .

My garden was ripped to pieces in the storm. It broke our birdhouses too. I have been raking leaves and tree limbs ever since the two storms. I don't feel so good. I got a cold since there was no heat in the place during the storms. Our government house is a good one though to have stood all it took.

In 1976, West Chop Light became the last Martha's Vineyard lighthouse to be automated.

Inside the tower

The original fourth order Fresnel lens remains in place. For some years, the Vineyard Environmental Research Institute used the houses at the station for its offices.

The house closest to the lighthouse now serves as living quarters for the officer in charge of Coast Guard Station Menemsha. The other house is now a vacation home for people in all branches of the military.

West Chop Light continues to exhibit its white flash, visible for 15 miles, as an active aid to navigation. It has a red sector to warn mariners away from two dangerous shoals.

The house closest to the lighthouse now serves as living quarters for the officer in charge of Coast Guard Station Menemsha. The other house is now a vacation home for people in all branches of the military.

West Chop Light continues to exhibit its white flash, visible for 15 miles, as an active aid to navigation. It has a red sector to warn mariners away from two dangerous shoals.

The grounds are closed to the public, but the lighthouse can be seen from West Chop Road and is also easily viewed from the ferries to and from Vineyard Haven.

The spiral stairs in the tower

Keepers:

(This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

James West (1818-1847); Charles West (1847-1869); Charles P. West (1869-1909); George F. Dolby (1909-1919); James Yates (1919-?); Carl Delano Hill (c. 1922); Sam Fuller (assistant, c. 1950s); Octave Ponsart (1946-1956); Fred Gallop (Coast Guard, 1966-1968), Edward Trenn (Coast Guard, 1969-1970), Rick R. St. Pierre (Coast Guard, 1975)

(This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

James West (1818-1847); Charles West (1847-1869); Charles P. West (1869-1909); George F. Dolby (1909-1919); James Yates (1919-?); Carl Delano Hill (c. 1922); Sam Fuller (assistant, c. 1950s); Octave Ponsart (1946-1956); Fred Gallop (Coast Guard, 1966-1968), Edward Trenn (Coast Guard, 1969-1970), Rick R. St. Pierre (Coast Guard, 1975)