History of Whaleback Light, Kittery, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Whaleback Lighthouse marks the approach to the harbor of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and has often been referred to as a New Hampshire lighthouse, but this rugged granite tower is clearly is in Maine waters by about 1500 feet.

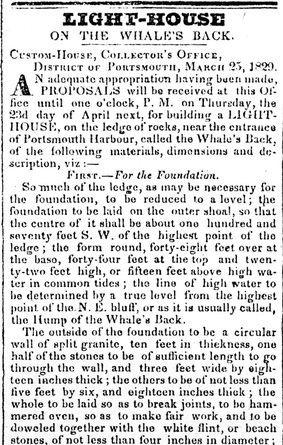

1829 request for bids

The jagged ledge known as Whaleback lurks menacingly on the northeast side of the entrance to the Piscataqua River, approximately a half -mile south of Gerrish Island, part of the town of Kittery. The ledge, which is completely underwater at high tide, is, in fact, a continuation of the southern point of Gerrish Island.

Portsmouth, on the Piscataqua River, was established as an important port for shipbuilding and trade before the American Revolution, and the first federal shipyard in the United States was established on the Kittery side of the Piscataqua River in 1800. Wrecks occurred around the mouth of the river with sickening regularity.

One of the earliest known shipwrecks at Whaleback Ledge occurred in February 1733, when a schooner ran onto the rocks and suffered damage that eventually sank the vessel. Two of the five men on board drowned; the Boston Newsletter reported that the other three, “tho’ much chilled with the Cold,” were likely to survive.

In April 1821, the schooner President, heading to Thomaston, Maine, from Boston, struck the ledge. The vessel and its cargo were a complete loss. As the crew and passengers struggled in the waves, several boats full of soldiers arrived from Fort Constitution in New Castle, New Hampshire. Most of the would-be rescuers opted not to get too close to the ledges in the heavy seas. According to a newspaper account, Corporal George McAuley asked his crew, “Shall we save them or perish in the attempt?” The response was unanimously “Yes,” and seven people from the wrecked vessel were soon rescued from certain death.

Portsmouth, on the Piscataqua River, was established as an important port for shipbuilding and trade before the American Revolution, and the first federal shipyard in the United States was established on the Kittery side of the Piscataqua River in 1800. Wrecks occurred around the mouth of the river with sickening regularity.

One of the earliest known shipwrecks at Whaleback Ledge occurred in February 1733, when a schooner ran onto the rocks and suffered damage that eventually sank the vessel. Two of the five men on board drowned; the Boston Newsletter reported that the other three, “tho’ much chilled with the Cold,” were likely to survive.

In April 1821, the schooner President, heading to Thomaston, Maine, from Boston, struck the ledge. The vessel and its cargo were a complete loss. As the crew and passengers struggled in the waves, several boats full of soldiers arrived from Fort Constitution in New Castle, New Hampshire. Most of the would-be rescuers opted not to get too close to the ledges in the heavy seas. According to a newspaper account, Corporal George McAuley asked his crew, “Shall we save them or perish in the attempt?” The response was unanimously “Yes,” and seven people from the wrecked vessel were soon rescued from certain death.

More wrecks followed in the ensuing years, including that of the Maine schooner Fame in October 1827. Congress had appropriated a sum of $1,500 in March 1827 for a lighthouse on the ledge, but that was plainly not enough money to build a lighthouse in such an exposed position.

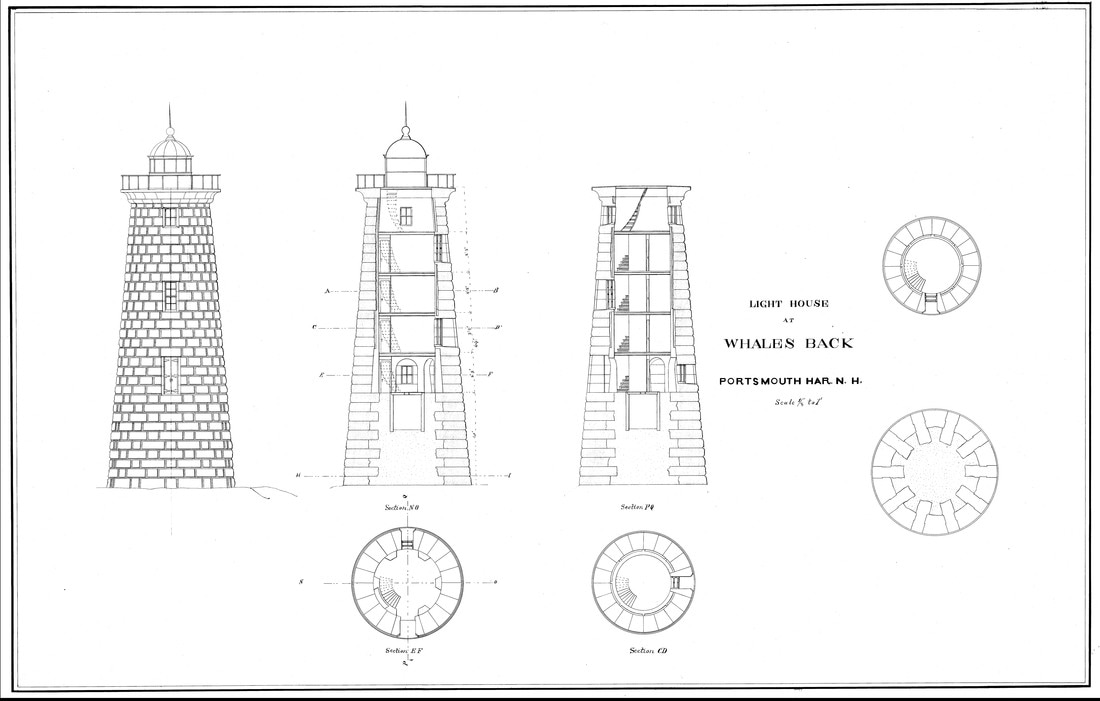

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

In February 1828, the sloop Aurora from Newburyport ran into Whaleback Ledge, and the Portsmouth Journal asked, “How many more wrecks must be made before Congress will make an appropriation for this object [a lighthouse]?”

Two more appropriations were made by 1829, largely through the efforts of New Hampshire Representative Ichabod Bartlett. The three appropriations totaled $20,000. The first Whaleback (called “Whales Back” or “Whalesback” in early records) Lighthouse was constructed in 1829–30.

Daniel Haselton and William Palmer were the contractors who carried out the work. Haselton was a New Hampshire native who had built the Baptist church on Middle Street in Portsmouth. He later built the original stone lighthouse at Robbins Reef in New York Harbor (1839). Haselton and Palmer also built the custom house in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Nearby Wood Island was utilized as a base for the construction project. Work on the lower courses could only take place only for a few hours around low tide. The lighthouse was erected on a conical granite pier, 42 feet in diameter at the bottom and 32 feet at the top. The 38-foot tower was 22 feet in diameter at its base, and 11 feet at the top.

To differentiate it from other aids to navigation in the vicinity, the lighthouse exhibited two fixed white lights, one 10 feet above the other. The lower light remained in operation until 1855. The upper light, in an octagonal wrought- iron lantern, was 58 feet above mean high water. Inside the tower were four rooms of living space on two levels, with a cellar. A wooden storage shed stood near the lighthouse. The first keeper, at $500 yearly, was Samuel E. Hascall, and the lighthouse went into service on September 16, 1830.

It was painfully clear that the tower had been poorly built; it leaked badly in storms and heavy seas. Contractor Winslow Lewis, a contractor who built many lighthouses, and mason Calvin Knowlton, a mason, surveyed the site and pointed out that the ledge hadn’t been leveled before construction began, and that small stones were improperly used to fill in gaps near the bottom. They recommended that a breakwater be added on the eastern side of the tower, at a cost of $20,000. “This rock is favorable for erecting a breakwater in it,” they concluded, “in the most permanent manner, and, if so built, would entirely protect the foundation of the light-house from any exposure from the effects of the sea, and remain for ages to come.”

Some wooden sheathing added around the tower in 1837 apparently helped the leaking problem of leaks, but Hascall reported that the tower rocked and shook increasingly in storms. Funds for the recommended breakwater were appropriated in 1837–38.

Two more appropriations were made by 1829, largely through the efforts of New Hampshire Representative Ichabod Bartlett. The three appropriations totaled $20,000. The first Whaleback (called “Whales Back” or “Whalesback” in early records) Lighthouse was constructed in 1829–30.

Daniel Haselton and William Palmer were the contractors who carried out the work. Haselton was a New Hampshire native who had built the Baptist church on Middle Street in Portsmouth. He later built the original stone lighthouse at Robbins Reef in New York Harbor (1839). Haselton and Palmer also built the custom house in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Nearby Wood Island was utilized as a base for the construction project. Work on the lower courses could only take place only for a few hours around low tide. The lighthouse was erected on a conical granite pier, 42 feet in diameter at the bottom and 32 feet at the top. The 38-foot tower was 22 feet in diameter at its base, and 11 feet at the top.

To differentiate it from other aids to navigation in the vicinity, the lighthouse exhibited two fixed white lights, one 10 feet above the other. The lower light remained in operation until 1855. The upper light, in an octagonal wrought- iron lantern, was 58 feet above mean high water. Inside the tower were four rooms of living space on two levels, with a cellar. A wooden storage shed stood near the lighthouse. The first keeper, at $500 yearly, was Samuel E. Hascall, and the lighthouse went into service on September 16, 1830.

It was painfully clear that the tower had been poorly built; it leaked badly in storms and heavy seas. Contractor Winslow Lewis, a contractor who built many lighthouses, and mason Calvin Knowlton, a mason, surveyed the site and pointed out that the ledge hadn’t been leveled before construction began, and that small stones were improperly used to fill in gaps near the bottom. They recommended that a breakwater be added on the eastern side of the tower, at a cost of $20,000. “This rock is favorable for erecting a breakwater in it,” they concluded, “in the most permanent manner, and, if so built, would entirely protect the foundation of the light-house from any exposure from the effects of the sea, and remain for ages to come.”

Some wooden sheathing added around the tower in 1837 apparently helped the leaking problem of leaks, but Hascall reported that the tower rocked and shook increasingly in storms. Funds for the recommended breakwater were appropriated in 1837–38.

Lewis and Knowlton had devised no specific plan for the breakwater, so the local customs collector and lighthouse superintendent, Daniel P. Drown, brought in the famed Boston architect and engineer Alexander Parris as a consultant.

Alexander Parris

Parris wrote that the lighthouse had been “constructed without science or workmanship.” In one great storm on July 7, 1837, according to Parris, the shaking vibrations was were so violent that “some of the small stones of the tower were shaken out and fell upon the floors of the rooms, and articles of furniture were displaced by the motion of the tower.”

Parris felt that a breakwater would afford little protection, and advised instead that a new lighthouse should be built for $75,000. He recommended a substantial masonry tower similar to the early waveswept lighthouses in the British Isles. The great military architect Colonel Sylvanus Thayer concurred, saying, “It is expedient to take down the present structure, and erect in its place a good and substantial building.” The breakwater was never built, and nothing would be done for more than 30 years other than repairs to the existing structures.

A storm in January 1839 dislodged a giant rock that tore away the iron ladder on the foundation. The assistant keepers, working in the lantern room, couldn’t hear each other speak during the gale because the shaking of the apparatus was so violent.

Portsmouth customs collector and local lighthouse suprintendent Daniel Drown, in 1839, called the tower "exceedingly dangerous," and recommended that the light be discontinued until a new tower could be erected. Fifth Auditor of the Treasury Stephen Pleasanton, in charge of the nation's lighthouses, said in 1842 that he was "in daily expectation that the present building has been demolished by the sea." Iron clamps were put around the foundation as reinforcement, but they soon broke away in winter storms.

One option considered for a while in the late 1840s was the building of an iron-pile lighthouse similar to the ill-fated one at Minot's Ledge in Massachusetts. $25,000 was appropriated for the building of a new tower, but the old one was refurbished instead.

Somehow the 1830 tower survived for more than 40 years. An 1850 inspection reported that some repointing was done around the base and that the lantern and dome had been painted inside and out.

Jedediah Rand of nearby Rye, New Hampshire, was principal keeper from 1849 to 1853. The lighthouse later became a “stag” station with male keepers only, but the families of some of the early keepers lived in the tower. Rand generally had one of his children with him. In September 1849, his 15-year-old daughter, Elizabeth Jane, spent three weeks at the lighthouse with her father.

On September 25, Rand launched the station’s small boat to take his daughter to New Castle, but it was swiftly overturned by a large wave. The keeper swam to his daughter and pulled to her to his side as he clung to the bottom of the boat. Another wave righted the boat and threw the pair into the ocean; again, Rand pulled his daughter to safety. A third wave upset the boat. By this time, Elizabeth had lost all her strength. Her father held her tightly and hung onto the boat. Elizabeth muttered, “Father, do I not love you . . . I want to go to heaven,” just before she lost consciousness.

The crew of a passing schooner heard Rand’s cries for help. A boat was dispatched to rescue the Rands, and they were taken to New Castle. Before they reached land, the apparently lifeless Elizabeth was revived. It was reported that her strong attachment to her father led her to return to the lighthouse with him that same afternoon, rather than recover with strangers in New Castle.

A fourth-order Fresnel lens, displaying a fixed white light varied by more intense flashes every 90 seconds, replaced the earlier lighting apparatus in 1855.

Parris felt that a breakwater would afford little protection, and advised instead that a new lighthouse should be built for $75,000. He recommended a substantial masonry tower similar to the early waveswept lighthouses in the British Isles. The great military architect Colonel Sylvanus Thayer concurred, saying, “It is expedient to take down the present structure, and erect in its place a good and substantial building.” The breakwater was never built, and nothing would be done for more than 30 years other than repairs to the existing structures.

A storm in January 1839 dislodged a giant rock that tore away the iron ladder on the foundation. The assistant keepers, working in the lantern room, couldn’t hear each other speak during the gale because the shaking of the apparatus was so violent.

Portsmouth customs collector and local lighthouse suprintendent Daniel Drown, in 1839, called the tower "exceedingly dangerous," and recommended that the light be discontinued until a new tower could be erected. Fifth Auditor of the Treasury Stephen Pleasanton, in charge of the nation's lighthouses, said in 1842 that he was "in daily expectation that the present building has been demolished by the sea." Iron clamps were put around the foundation as reinforcement, but they soon broke away in winter storms.

One option considered for a while in the late 1840s was the building of an iron-pile lighthouse similar to the ill-fated one at Minot's Ledge in Massachusetts. $25,000 was appropriated for the building of a new tower, but the old one was refurbished instead.

Somehow the 1830 tower survived for more than 40 years. An 1850 inspection reported that some repointing was done around the base and that the lantern and dome had been painted inside and out.

Jedediah Rand of nearby Rye, New Hampshire, was principal keeper from 1849 to 1853. The lighthouse later became a “stag” station with male keepers only, but the families of some of the early keepers lived in the tower. Rand generally had one of his children with him. In September 1849, his 15-year-old daughter, Elizabeth Jane, spent three weeks at the lighthouse with her father.

On September 25, Rand launched the station’s small boat to take his daughter to New Castle, but it was swiftly overturned by a large wave. The keeper swam to his daughter and pulled to her to his side as he clung to the bottom of the boat. Another wave righted the boat and threw the pair into the ocean; again, Rand pulled his daughter to safety. A third wave upset the boat. By this time, Elizabeth had lost all her strength. Her father held her tightly and hung onto the boat. Elizabeth muttered, “Father, do I not love you . . . I want to go to heaven,” just before she lost consciousness.

The crew of a passing schooner heard Rand’s cries for help. A boat was dispatched to rescue the Rands, and they were taken to New Castle. Before they reached land, the apparently lifeless Elizabeth was revived. It was reported that her strong attachment to her father led her to return to the lighthouse with him that same afternoon, rather than recover with strangers in New Castle.

A fourth-order Fresnel lens, displaying a fixed white light varied by more intense flashes every 90 seconds, replaced the earlier lighting apparatus in 1855.

In the early hours of February 15, 1863, the British schooner Rouser, on its way to Boston from St. John, New Brunswick, was wrecked close to Whaleback Ledge.

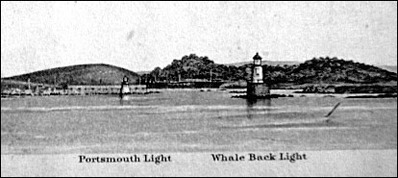

Right: This 1866 illustration shows the 1804 Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in New Castle, NH, and the 1831 Whaleback Lighthouse.

It was reported that the lighthouse keeper looked out the window of the tower at 5:00 a.m. and saw a piece of the wreck, along with three men. One of the men called to the keeper, pleading that for him to throw them a line. The keeper immediately complied but the seas were too rough for the men to be saved. All seven men on board the Rouser died in the tragedy.

Soon after the wreck it was announced that a new fog bell and tower had been installed at the lighthouse. The bell tower was described as a "frame structure, 25 feet high, whitewashed, standing upon the Light House pier, and attached to the southerly part of the Light House tower." When needed, the bell was struck by machinery four times every minute.

It was reported that the lighthouse keeper looked out the window of the tower at 5:00 a.m. and saw a piece of the wreck, along with three men. One of the men called to the keeper, pleading that for him to throw them a line. The keeper immediately complied but the seas were too rough for the men to be saved. All seven men on board the Rouser died in the tragedy.

Soon after the wreck it was announced that a new fog bell and tower had been installed at the lighthouse. The bell tower was described as a "frame structure, 25 feet high, whitewashed, standing upon the Light House pier, and attached to the southerly part of the Light House tower." When needed, the bell was struck by machinery four times every minute.

In spite of the light and fog bell, the area was still treacherous in bad weather. In February 1871, a Nova Scotian schooner ran onto the ledge in a blinding snowstorm. The vessel broke apart and the crew was lost.

The 1872 tower was built next to the earlier one

While walking the shore, William C. Williams of Kittery, later a keeper at Boon Island, found letters and books that had belonged to the crewmen. Williams wrote that he “thought of the dear friends that would see them no more.”

In March 1871, Keeper Ferdinand Barr, a Civil War veteran, drowned in heavy seas while away from the lighthouse tending his lobster traps. According to a newspaper report, a "signal of distress was made from the light-house by his children, who were alone at the time, the mother being in this city, and though the watchman at the U.S. Hospital on Wood Island, Mr. James Andrews, and a fisherman named Wallace, went to the rescue, it was too late, as the unfortunate man had disappeared." Keeper Barr was said to be a Prussian by birth. He was about 30 years old and left his wife and three children.

Storms in 1869 caused cracks in the tower and foundation, and a report stated, "The station should be rebuilt as soon as possible."A new lighthouse tower was finally erected in 1872 for $75,000. The new tower, 27 feet in diameter at its base and about 70 feet tall to the very top of its lantern dome, was constructed of granite blocks dovetailed together in similar fashion to Minot’s Ledge Light in Massachusetts and England’s Eddystone Light. General James Chatham Duane, engineer for the Lighthouse Board’s first and second districts, was involved with the design. The granite came from the Goodwin Granite Quarry in Biddeford, Maine, and was supplied by the partnership of Gooch and Haines.

In March 1871, Keeper Ferdinand Barr, a Civil War veteran, drowned in heavy seas while away from the lighthouse tending his lobster traps. According to a newspaper report, a "signal of distress was made from the light-house by his children, who were alone at the time, the mother being in this city, and though the watchman at the U.S. Hospital on Wood Island, Mr. James Andrews, and a fisherman named Wallace, went to the rescue, it was too late, as the unfortunate man had disappeared." Keeper Barr was said to be a Prussian by birth. He was about 30 years old and left his wife and three children.

Storms in 1869 caused cracks in the tower and foundation, and a report stated, "The station should be rebuilt as soon as possible."A new lighthouse tower was finally erected in 1872 for $75,000. The new tower, 27 feet in diameter at its base and about 70 feet tall to the very top of its lantern dome, was constructed of granite blocks dovetailed together in similar fashion to Minot’s Ledge Light in Massachusetts and England’s Eddystone Light. General James Chatham Duane, engineer for the Lighthouse Board’s first and second districts, was involved with the design. The granite came from the Goodwin Granite Quarry in Biddeford, Maine, and was supplied by the partnership of Gooch and Haines.

The work of leveling the ledge began in the summer of 1870. The original tower remained standing while the new one was built. The process was slow, as it could take place only at low tide. The 1871 annual report of the Lighthouse Board announced that the masonry had been completed to a height of 20 feet above the low water mark.

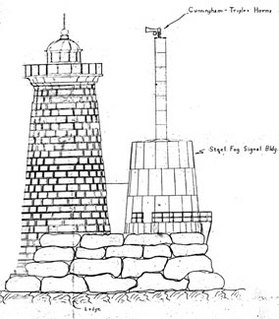

Plans for the 1878 fog signal tower

The laying of the last stone in August 1871 was followed by the installation of the lantern and other ironwork, and the lighting apparatus. The tower is lined with brick, with hard pine floors, cast-iron staircases, and iron ceilings. Horizontal I-beams lend support for each of the four floors. A basement provided storage space for water and fuel.

William H. Caswell was the principal keeper when the new tower was completed, and his son, Frank, was one of his assistants. In November 1871, Caswell proclaimed the new tower “perfectly safe” and noted that it didn’t even tremble in a storm. By the 1872 annual report, the new tower had gone into operation. At the time it was built, the focal plane height was reported as 68 feet, but the height is given as 59 feet on recent light lists.

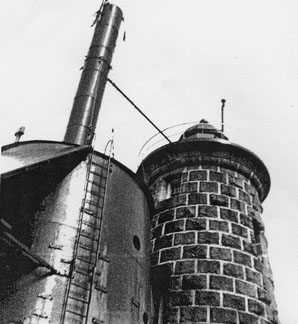

The 1831 tower remained standing while the new one was built. Beginning in 1877, the old tower briefly served as a fog signal house with the installation of a new Daboll fog trumpet. Access to the rickety building was difficult in rough weather, so a new plan was devised.

In 1878, a new cast-iron tower was built just to the north of the 1872 lighthouse to serve as a fog signal house. The tower, about half as tall as the lighthouse, was surmounted by a long iron tube and a third-class fog trumpet. This fog signal tower was painted red for some years. The remains of the original lighthouse were torn down in 1880.

William H. Caswell was the principal keeper when the new tower was completed, and his son, Frank, was one of his assistants. In November 1871, Caswell proclaimed the new tower “perfectly safe” and noted that it didn’t even tremble in a storm. By the 1872 annual report, the new tower had gone into operation. At the time it was built, the focal plane height was reported as 68 feet, but the height is given as 59 feet on recent light lists.

The 1831 tower remained standing while the new one was built. Beginning in 1877, the old tower briefly served as a fog signal house with the installation of a new Daboll fog trumpet. Access to the rickety building was difficult in rough weather, so a new plan was devised.

In 1878, a new cast-iron tower was built just to the north of the 1872 lighthouse to serve as a fog signal house. The tower, about half as tall as the lighthouse, was surmounted by a long iron tube and a third-class fog trumpet. This fog signal tower was painted red for some years. The remains of the original lighthouse were torn down in 1880.

James W. Verney, a native of Bath, Maine, was keeper 1869-71. Verney had served as a chief quartermaster on the USS Pontoosuc during the Wilmington Campaign in the Civil War, and he was awarded a Medal of Honor "for gallantry and skill and for his cool courage while under fire of the enemy."

In July 1882, assistant keeper John Lewis fell from the fog signal tower as he was painting it; he died from his injuries several days later at his home in Kittery.

Left: In this National Archives photo from the late 1800s the fog signal can be seen on the iron tower next to the lighthouse. Notice the boat hanging on davits on the right.

A storm in 1886 sent waves smashing through a window of the tower, flooding the living quarters. Keeper Leander White displayed a blanket from the tower as a distress signal. Two Kittery residents, Walter S. Amee and Samuel Blake, reached Whaleback as the storm abated and rushed White to medical facilities.

The great blizzard of March 1888 destroyed much of the remaining foundation of the old tower. A gale in November of the same year left 2,000 tons of stones from the base of the old lighthouse around the new tower. Another storm in 1892 left huge rocks blocking the entrance to the lighthouse.

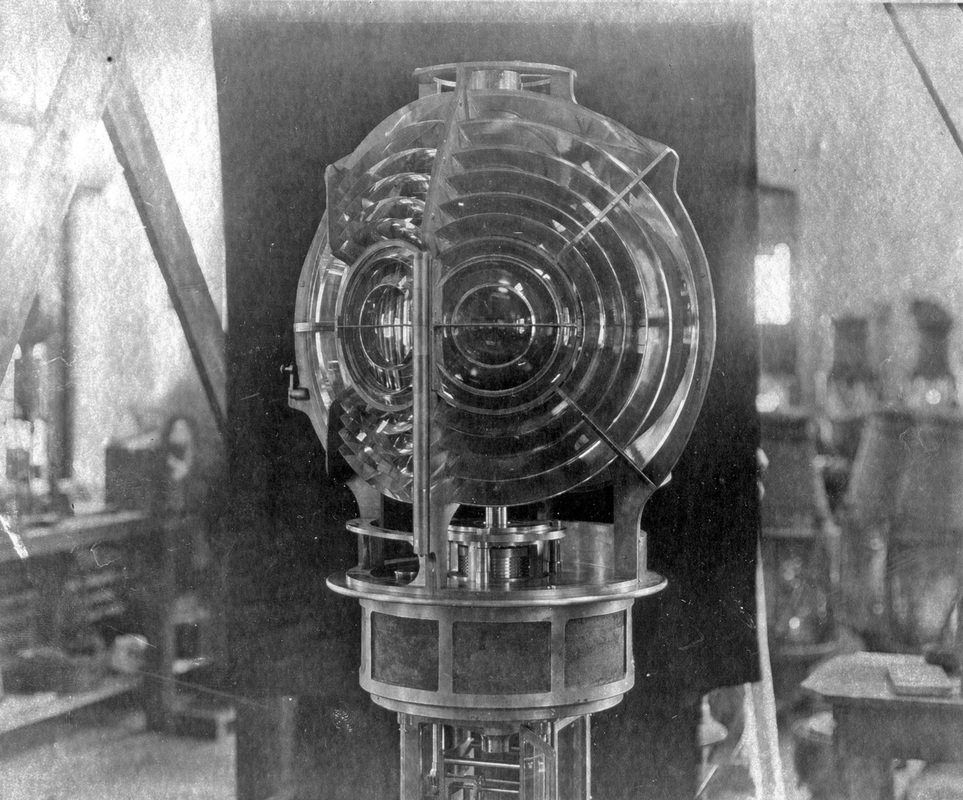

A new revolving fourth-order lens was installed in 1898. That lens was replaced in 1912, at the same time that a new I.O.V. (incandescent oil vapor) lamp was installed. The lens installed in 1912 had been manufactured in France by the firm of Barbier, Bernard, and Turenne in 1911. The lens rotated atop a new pedestal, on a groove filled with mercury. The new system produced two quick flashes every 10 seconds.

A storm in 1886 sent waves smashing through a window of the tower, flooding the living quarters. Keeper Leander White displayed a blanket from the tower as a distress signal. Two Kittery residents, Walter S. Amee and Samuel Blake, reached Whaleback as the storm abated and rushed White to medical facilities.

The great blizzard of March 1888 destroyed much of the remaining foundation of the old tower. A gale in November of the same year left 2,000 tons of stones from the base of the old lighthouse around the new tower. Another storm in 1892 left huge rocks blocking the entrance to the lighthouse.

A new revolving fourth-order lens was installed in 1898. That lens was replaced in 1912, at the same time that a new I.O.V. (incandescent oil vapor) lamp was installed. The lens installed in 1912 had been manufactured in France by the firm of Barbier, Bernard, and Turenne in 1911. The lens rotated atop a new pedestal, on a groove filled with mercury. The new system produced two quick flashes every 10 seconds.

|

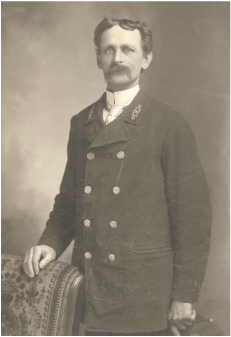

Walter S. Amee became keeper at Whaleback in 1893. Amee had gone to sea as a young man aboard the Kittery-based schooner Eldorado. He stayed ashore when the vessel left for a fishing expedition on the Grand Banks in 1873. That proved to have been a wise decision, as the vessel and its crew were never heard from again. Amee went on to captain fishing schooners out of Salem, Massachusetts, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, before brief stints as an assistant keeper at Boon Island, Maine, and White Island, New Hampshire.

Amee remained in charge until 1921, a remarkably long stay at a difficult offshore station. His first assistant keeper for most of those years was John Wetzel of Portsmouth, who held the position from 1897 to 1924. John Brooks of Kittery was the second assistant keeper from 1899 to 1915. The three men obviously had to have a congenial relationship in the confined quarters, and a 1911 article in the Boston Globe stated that they refused offers of positions at other Maine stations. |

At the time of the 1911 article, the men each spent four days on duty followed by two days on shore. That schedule was often disrupted by rough weather and sea conditions. It was said that up to that time, Amee had spent only 11 days out of sight of the lighthouse in 18 years.

Amee performed a brave rescue during a storm in August 1899, when a small boat with two men aboard capsized near the lighthouse. While one of the assistant keepers blasted the foghorn repeatedly in an attempt to get the attention of the men at a nearby lifesaving station, Amee launched the small lighthouse boat and managed to haul the drowning men aboard.

Amee performed a brave rescue during a storm in August 1899, when a small boat with two men aboard capsized near the lighthouse. While one of the assistant keepers blasted the foghorn repeatedly in an attempt to get the attention of the men at a nearby lifesaving station, Amee launched the small lighthouse boat and managed to haul the drowning men aboard.

In July 1911, two young men from York, Maine, were entering the Piscataqua River in their powerboat when it hit a rock and developed a fast leak. Their cries for help were heard by Amee, who launched a boat and reached the men, then took them back to the lighthouse for the night.

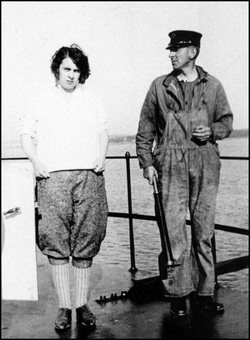

Arnold White (Courtesy of Chuck Petlick)

John Wetzel died suddenly at his home in Portsmouth in December 1924. Wetzel, who had tended the range lights at Henderson Point in Kittery before taking the first assistant position at Whaleback, was only 57 years old; his death was attributed to a cerebral hemorrhage. The Portsmouth Herald described him as a “man of quiet tastes and generous disposition.”

Arnold B. White of New Castle, New Hampshire, son of the former keeper Leander White, succeeded Amee as principal keeper in 1921. He would be the station’s last civilian keeper. When the Coast Guard took over operation of the nation’s lighthouses in 1939, keepers were given the option of joining the Coast Guard or serving out the remainder of their careers as civilians. White joined the Coast Guard in 1941, shortly before he was transferred from Whaleback to Portsmouth Harbor Light, New Hampshire. Maynard Farnsworth, an assistant under White since the 1920s, became the next Coast Guard officer in charge in 1941.

Arnold White was in charge when Justine Flint of the Portsmouth Herald described a visit to Whaleback Ledge in 1939:

On arriving at the landing-stage of the light, Captain Arnold B. White, the keeper, was waiting with a smiling welcome. . . . Captain White has lived in this solitary wind-swept setting for 18 years and once during that time when ice filled the Piscataqua in 1924 he was unable to go ashore for 14 days. Because the government rules that only members of the crew may live there permanently, his wife must remain in town. Visitors are welcome, however, and Mrs. White often spends several days with him.

Arnold B. White of New Castle, New Hampshire, son of the former keeper Leander White, succeeded Amee as principal keeper in 1921. He would be the station’s last civilian keeper. When the Coast Guard took over operation of the nation’s lighthouses in 1939, keepers were given the option of joining the Coast Guard or serving out the remainder of their careers as civilians. White joined the Coast Guard in 1941, shortly before he was transferred from Whaleback to Portsmouth Harbor Light, New Hampshire. Maynard Farnsworth, an assistant under White since the 1920s, became the next Coast Guard officer in charge in 1941.

Arnold White was in charge when Justine Flint of the Portsmouth Herald described a visit to Whaleback Ledge in 1939:

On arriving at the landing-stage of the light, Captain Arnold B. White, the keeper, was waiting with a smiling welcome. . . . Captain White has lived in this solitary wind-swept setting for 18 years and once during that time when ice filled the Piscataqua in 1924 he was unable to go ashore for 14 days. Because the government rules that only members of the crew may live there permanently, his wife must remain in town. Visitors are welcome, however, and Mrs. White often spends several days with him.

The assistants at the time were Maynard Farnsworth and Warren Alley. Flint described the cellar as “scrupulously clean.” A walled-in window was used as a cupboard for food supplies. A cistern in the cellar held drinking water, brought from Sebago Lake 2,000 gallons at a time.

Right: Assistant keeper Maynard Farnsworth with two unidentified women. Courtesy of Chuck Petlick.

The next level contained a small kitchen, “comfortable and cheerful, with good sized windows to admit air and sunshine.” The writer was amazed that the men were excellent housekeepers; the numerous brass articles were “kept as bright and glowing as a mirror.”

Testifying to the men’s exemplary work, the government awarded an efficiency pennant to the crew in 1938. The award was given for an inspection rating of 95 percent or better. White explained his general philosophy: “The government tolerates no excuses. You must anticipate trouble and have spare parts on hand at all times.”

Flint noted that the tower’s ten windows—with the glass a half -inch thick—were screened to keep out the houseflies that sometimes arrived in swarms.

The next level contained a small kitchen, “comfortable and cheerful, with good sized windows to admit air and sunshine.” The writer was amazed that the men were excellent housekeepers; the numerous brass articles were “kept as bright and glowing as a mirror.”

Testifying to the men’s exemplary work, the government awarded an efficiency pennant to the crew in 1938. The award was given for an inspection rating of 95 percent or better. White explained his general philosophy: “The government tolerates no excuses. You must anticipate trouble and have spare parts on hand at all times.”

Flint noted that the tower’s ten windows—with the glass a half -inch thick—were screened to keep out the houseflies that sometimes arrived in swarms.

When asked what the men ate, White explained that they had tried a system whereby one man was cook for the day. That didn’t last, because their tastes were all different. Lobster was a staple, and peaches and cream were was a preferred dessert.

Left: Arnold White and his daughter Muriel. Courtesy of Chuck Petlick.

White’s dumplings were “an epicurean’s dream.” This praise has been echoed by White’s daughter, Marion White Petlick of Rye, New Hampshire, who fondly recalled visits to the lighthouse as a girl in a 2004 interview. Her father usually had some kind of baked treat, such as bread pudding, cooling on a windowsill.

The principal keeper’s quarters were on the floor above the kitchen, and everything was neat and orderly, the furnishings modest. A barometer hung on the wall; the keepers were required to fill out weather reports every four hours. A ship’s medicine chest was also kept in this area. White told of a visitor who had once slipped and cut her arm on the rocks. He dressed and bandaged the woman’s injury, and a doctor later said that he had done the job perfectly.

In December 1948, historian Edward Rowe Snow -- famous as the "Flying Santa" to lighthouse keepers -- dropped a bundle from a plane containing Christmas gifts for the keepers at Whaleback Light. Snow's first drop was too far away for the keepers to recover. Three weeks later, Eugene S. Clark was walking on a beach in Sandwich on Cape Cod. He found the package 90 miles from where it had been dropped. Snow reported that years later Clark still had the book that was in the package, Snow's Storms and Shipwrecks of New England.

White’s dumplings were “an epicurean’s dream.” This praise has been echoed by White’s daughter, Marion White Petlick of Rye, New Hampshire, who fondly recalled visits to the lighthouse as a girl in a 2004 interview. Her father usually had some kind of baked treat, such as bread pudding, cooling on a windowsill.

The principal keeper’s quarters were on the floor above the kitchen, and everything was neat and orderly, the furnishings modest. A barometer hung on the wall; the keepers were required to fill out weather reports every four hours. A ship’s medicine chest was also kept in this area. White told of a visitor who had once slipped and cut her arm on the rocks. He dressed and bandaged the woman’s injury, and a doctor later said that he had done the job perfectly.

In December 1948, historian Edward Rowe Snow -- famous as the "Flying Santa" to lighthouse keepers -- dropped a bundle from a plane containing Christmas gifts for the keepers at Whaleback Light. Snow's first drop was too far away for the keepers to recover. Three weeks later, Eugene S. Clark was walking on a beach in Sandwich on Cape Cod. He found the package 90 miles from where it had been dropped. Snow reported that years later Clark still had the book that was in the package, Snow's Storms and Shipwrecks of New England.

One of the Coast Guard keepers in the 1940s, Morgan Willis, passed some of the lonely hours by chatting with local telephone operators. He asked one of them for a date; they eventually married and spent their honeymoon at the Cape Neddick Lighthouse in York, Maine.

Morgan Willis, courtesy of Lighthouse Digest

A 1957 magazine story reported that the Coast Guard keepers at Whaleback had two days leave between eight-day stays at the lighthouse. There were quarters for four in the tower, but there were usually two or three on duty at one time.

The article described the difficulties the Coast Guardsmen sometimes had getting on and off the station. Engineman Third Class Francis D. Hickey left to go ashore on New Year's Eve in 1956, only to lose his power. His boat drifted for six hours before he was found by a Coast Guard cutter.

Jim Pope, a native of Kittery, was one of the last Coast Guard crewmen before automation. When Pope arrived at the station at the age of 19 in 1960, the men had 24-day stints on duty followed by six days off. When a navigational light at Odiorne Point in Rye, New Hampshire, disappeared in the fog, it was time to activate Whaleback’s foghorn. The horn once ran for 18 straight days during a foggy stretch in 1961.

Pope enjoyed fishing around the tower, and he occasionally shot ducks from the lighthouse’s windows. When it was time to get supplies, he rowed to shore in the station’s 16-foot skiff and borrowed the car of a Kittery resident to make a run to the nearby A&P grocery store.

The article described the difficulties the Coast Guardsmen sometimes had getting on and off the station. Engineman Third Class Francis D. Hickey left to go ashore on New Year's Eve in 1956, only to lose his power. His boat drifted for six hours before he was found by a Coast Guard cutter.

Jim Pope, a native of Kittery, was one of the last Coast Guard crewmen before automation. When Pope arrived at the station at the age of 19 in 1960, the men had 24-day stints on duty followed by six days off. When a navigational light at Odiorne Point in Rye, New Hampshire, disappeared in the fog, it was time to activate Whaleback’s foghorn. The horn once ran for 18 straight days during a foggy stretch in 1961.

Pope enjoyed fishing around the tower, and he occasionally shot ducks from the lighthouse’s windows. When it was time to get supplies, he rowed to shore in the station’s 16-foot skiff and borrowed the car of a Kittery resident to make a run to the nearby A&P grocery store.

Here is an edited 2018 interview with Jim conducted by videographer Jim White and USLHS historian Jeremy D’Entremont, recorded at the Kittery Historical and Naval Museum.

Above: Coast Guard crewmen working on the fog signal equipment at Whaleback in 1957 (from New Hampshire Profiles magazine).

After his time in the Coast Guard, Pope went on to a long career as a local tugboat captain.

The light was automated in 1963 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by rotating aerobeacons. In 1991, the Coast Guard found that the fog signal was causing structural damage to the tower, so they lowered its volume.

In the fall of 2002 the rotating aerobeacons were replaced by a smaller VRB-25 optic.

In October 2009, the VRB-25 was replaced by a solar powered VLB-44 LED optic.

After his time in the Coast Guard, Pope went on to a long career as a local tugboat captain.

The light was automated in 1963 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by rotating aerobeacons. In 1991, the Coast Guard found that the fog signal was causing structural damage to the tower, so they lowered its volume.

In the fall of 2002 the rotating aerobeacons were replaced by a smaller VRB-25 optic.

In October 2009, the VRB-25 was replaced by a solar powered VLB-44 LED optic.

The 1912 lens (above) is now in storage at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

Circa 1957

In 2007, under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, the lighthouse was made available to a suitable new steward. The American Lighthouse Foundation and its chapter, the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse, submitted an application.

In November 2008, it was announced that the Secretary of the Interior accepted the National Park Service's recommendation that the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF) be awarded ownership of the lighthouse.

Between 2009 and 2018, the lighthouse has been weatherproofed, the lantern, dome, deck, and other exterior ironwork has been repainted, the door has been repaired, and the interior has been cleaned. There are plans to install a docking system to facilitate further restoration and public visitation. The plans, developed with the assistance of a marine engineer, will cost about $300,000.

If you're interested in being part of the effort to restore and preserve this lighthouse, email [email protected]

Whaleback Light can be seen from Fort Foster in Kittery, Fort Constitution, Fort Stark, and Great Island Common in New Castle, NH, Odiorne Point in Rye, NH, and other spots on both the New Hampshire and Maine sides. It is also seen from tour boats leaving Portsmouth Harbor.

In November 2008, it was announced that the Secretary of the Interior accepted the National Park Service's recommendation that the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF) be awarded ownership of the lighthouse.

Between 2009 and 2018, the lighthouse has been weatherproofed, the lantern, dome, deck, and other exterior ironwork has been repainted, the door has been repaired, and the interior has been cleaned. There are plans to install a docking system to facilitate further restoration and public visitation. The plans, developed with the assistance of a marine engineer, will cost about $300,000.

If you're interested in being part of the effort to restore and preserve this lighthouse, email [email protected]

Whaleback Light can be seen from Fort Foster in Kittery, Fort Constitution, Fort Stark, and Great Island Common in New Castle, NH, Odiorne Point in Rye, NH, and other spots on both the New Hampshire and Maine sides. It is also seen from tour boats leaving Portsmouth Harbor.

Aerial video at low tide (March 2011)

Aerial views by Baystate Images

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Samuel E. Hascall (Haskell) (1831-1839); Joseph L. Locke (1839-1840); Zachariah Chickering (1840); John Kennard (1840); Joseph D. Currier (1841); Eliphalet Grover (1841-1843); J. Prentiss Locke (1843-?); Richard R. Lock (Locke?) (c. 1847); Jedediah Rand (1849-1853)l Reuben T. Leavitt (1853-1859); Oliver P. Tucker (1859-1860); Gustavus A. Abbott (1860-1861); Joel P. Reynolds (1861-1864); Edward Parks (assistant, 1863-1864); Nathaniel P. Campbell (1864); Ambrose Card (assistant, then keeper 1864); Gilbert Amee (assistant 1864, then keeper 1864-1869); Mrs. M. M. Amee (assistant, 1864-1867); Isaac W. Chauncy (assistant, 1867-1868); James W. Verney (1869-1871); Ferdinand Barr (assistant 1868-1871, became keeper 3/22/1871, drowned 6/18/1871); Emily F. Barr (assistant, 1871); William H. Caswell (1871-1872); Frank P. Caswell (assistant, 1871-1872); Chandler Martin (1872-1878); George R. Frost (assistant, 1872-1873); Frank L. Chauncey (assistant, 1873 and 1876-1880); John L. A. Martin (John Q. A. Martn?) (assistant 1874-1876); Leander White (1878-1887); John Lewis (assistant 1880-1882); Brackett Lewis (assistant 1883-1885); Ellison C. White (assistant 1885-1887, principal keeper 1887-1888); James M. Haley (1888-1893); Daniel Stevens (assistant 1887-1890); John W. Robinson (assistant 1890-1892); James Haley (Jr.?) (assistant 1892-1893); Walter S. Amee (1893-1921); Wallace S, Chase (assistant 1893-1894); Alvah J. Tobey (assistant 1894-1899); Joseph A. Pruett (assistant 1896-1897); John W. Wetzel (assistant 1897-1924); John P. Brooks (assistant, 1899-1915); Arnold B. White (1921-1941); Warren A. Alley (c. 1935); Maynard F. Farnsworth (second assistant 1921-1924, 1st assistant 1924-1941); Charles U. Gardner (relief keeper, c, 1942-1943); Morgan Willis (Coast Guard, circa 1940s); Henry Brown (Coast Guard, c. 1955-1956); Robert Bedard (Coast Guard, c. 1955-1956); Clifford D. Evans (Coast Guard, c. 1956); "Smiley" Smullen (Coast Guard, c. 1956); Francis D. Hickey (Coast Guard, c. 1956-1957); George Matheson (Coast Guard, c. 1958); Stephen H. Rogers (Coast Guard, c. 1956-1958); Robert Brann (Coast Guard, c. 1959); James Pope (Coast Guard, 1960-1962); William Beasley (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. early 1960s); Roger Phillips (Coast Guard, c. early 1960s); J. C. Yates (Coast Guard, c. 1960-1961); George Johns (Coast Guard, c. 1961-1962); ? Lambert (Coast Guard, early 1960s)

Samuel E. Hascall (Haskell) (1831-1839); Joseph L. Locke (1839-1840); Zachariah Chickering (1840); John Kennard (1840); Joseph D. Currier (1841); Eliphalet Grover (1841-1843); J. Prentiss Locke (1843-?); Richard R. Lock (Locke?) (c. 1847); Jedediah Rand (1849-1853)l Reuben T. Leavitt (1853-1859); Oliver P. Tucker (1859-1860); Gustavus A. Abbott (1860-1861); Joel P. Reynolds (1861-1864); Edward Parks (assistant, 1863-1864); Nathaniel P. Campbell (1864); Ambrose Card (assistant, then keeper 1864); Gilbert Amee (assistant 1864, then keeper 1864-1869); Mrs. M. M. Amee (assistant, 1864-1867); Isaac W. Chauncy (assistant, 1867-1868); James W. Verney (1869-1871); Ferdinand Barr (assistant 1868-1871, became keeper 3/22/1871, drowned 6/18/1871); Emily F. Barr (assistant, 1871); William H. Caswell (1871-1872); Frank P. Caswell (assistant, 1871-1872); Chandler Martin (1872-1878); George R. Frost (assistant, 1872-1873); Frank L. Chauncey (assistant, 1873 and 1876-1880); John L. A. Martin (John Q. A. Martn?) (assistant 1874-1876); Leander White (1878-1887); John Lewis (assistant 1880-1882); Brackett Lewis (assistant 1883-1885); Ellison C. White (assistant 1885-1887, principal keeper 1887-1888); James M. Haley (1888-1893); Daniel Stevens (assistant 1887-1890); John W. Robinson (assistant 1890-1892); James Haley (Jr.?) (assistant 1892-1893); Walter S. Amee (1893-1921); Wallace S, Chase (assistant 1893-1894); Alvah J. Tobey (assistant 1894-1899); Joseph A. Pruett (assistant 1896-1897); John W. Wetzel (assistant 1897-1924); John P. Brooks (assistant, 1899-1915); Arnold B. White (1921-1941); Warren A. Alley (c. 1935); Maynard F. Farnsworth (second assistant 1921-1924, 1st assistant 1924-1941); Charles U. Gardner (relief keeper, c, 1942-1943); Morgan Willis (Coast Guard, circa 1940s); Henry Brown (Coast Guard, c. 1955-1956); Robert Bedard (Coast Guard, c. 1955-1956); Clifford D. Evans (Coast Guard, c. 1956); "Smiley" Smullen (Coast Guard, c. 1956); Francis D. Hickey (Coast Guard, c. 1956-1957); George Matheson (Coast Guard, c. 1958); Stephen H. Rogers (Coast Guard, c. 1956-1958); Robert Brann (Coast Guard, c. 1959); James Pope (Coast Guard, 1960-1962); William Beasley (Coast Guard officer in charge, c. early 1960s); Roger Phillips (Coast Guard, c. early 1960s); J. C. Yates (Coast Guard, c. 1960-1961); George Johns (Coast Guard, c. 1961-1962); ? Lambert (Coast Guard, early 1960s)