History of Bakers Island Lighthouse, Salem, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Five miles out to sea from Salem lies Baker's Island. Its delightful insular aloofness makes it the ideal location for a summer colony, with the cottages, grassy terrain, and rocky sea-cliff -- Edward Rowe Snow, The Romance of Boston Bay

The historian Edward Rowe Snow wrote that 55-acre Baker’s Island was named for an early seventeenth- century visitor who was killed on the island by a falling tree. There doesn’t appear to be a record of such an incident, but it is a fact that in 1640 a man named Robert Baker was killed by a falling piece of lumber as a ship was being built on the mainland in Salem. It isn’t clear why—or if—the island was named for this unfortunate man.

The island, about three miles east of the entrance to Salem’s harbor, was first granted to Salem in 1660. For a time in the 1670s, the island was rented to John Turner, the builder of Salem’s celebrated House of the Seven Gables. It later passed into private ownership.

Today, it’s the state’s largest residential island north of Boston. The population is almost entirely seasonal; only a caretaker lives on the island in winter.

The island, about three miles east of the entrance to Salem’s harbor, was first granted to Salem in 1660. For a time in the 1670s, the island was rented to John Turner, the builder of Salem’s celebrated House of the Seven Gables. It later passed into private ownership.

Today, it’s the state’s largest residential island north of Boston. The population is almost entirely seasonal; only a caretaker lives on the island in winter.

Salem was already a well-established port for foreign trade by the late 1700s, but there were no major aids to navigation to help mariners past the islands and rocks outside the harbor. Aiming to fill this void, on May 25, 1791, the Salem Marine Society voted for a committee of three men to “Aract a Backon on Backers Island.”

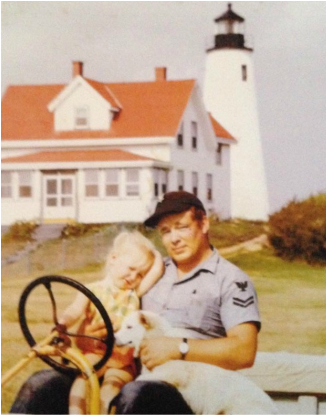

U.S. Coast Guard

A few weeks later they voted to spend the sum of £20 to erect an unlighted beacon. It was soon realized that additional funds were needed, so a public subscription paper was circulated in July 1791:

From the many accidents that has happen’d & frequent Mistakes made by Vessels coming into this Port in the Night & in thick weather for want of a Land Mark to ascertain Bakers Island so call’d we the Subscribers agree to give for the Purpose of building a Beacon on the Northernmost Part of Sd Island the Sums by us Subscribed . . .

Seventy-one persons signed and contributed an additional £89. On July 28, according to the Reverend Dr. William Bentley, “the intended Beacon was raised by a large & Jovial party.” The conical beacon was 57 feet tall, painted red, and topped by a two-foot diameter black ball. The foundation stones, said Bentley, were “very miserably laid.” Nevertheless, for the next five years the tower served as an important daytime guide to Salem Harbor.

The Salem Marine Society proceeded to establish buoys to improve local navigation, but by 1792 they set out to convince the local lighthouse superintendent, General Benjamin Lincoln, and the U.S. Congress that a lighted aid was sorely needed. The inadequacy of the day beacon was proven by the wrecks of three vessels in 1796, with in 16 lives were lost. The Marine Society sent a letter to Congress:

That much of the property and many of the lives of their fellow citizens are almost every year lost in coming into the harbour of Salem for want of proper lights to direct their course... This calamity can, in the opinion of this society be prevented only by erecting a lighthouse on the northern end of Bakers Island . . .

From the many accidents that has happen’d & frequent Mistakes made by Vessels coming into this Port in the Night & in thick weather for want of a Land Mark to ascertain Bakers Island so call’d we the Subscribers agree to give for the Purpose of building a Beacon on the Northernmost Part of Sd Island the Sums by us Subscribed . . .

Seventy-one persons signed and contributed an additional £89. On July 28, according to the Reverend Dr. William Bentley, “the intended Beacon was raised by a large & Jovial party.” The conical beacon was 57 feet tall, painted red, and topped by a two-foot diameter black ball. The foundation stones, said Bentley, were “very miserably laid.” Nevertheless, for the next five years the tower served as an important daytime guide to Salem Harbor.

The Salem Marine Society proceeded to establish buoys to improve local navigation, but by 1792 they set out to convince the local lighthouse superintendent, General Benjamin Lincoln, and the U.S. Congress that a lighted aid was sorely needed. The inadequacy of the day beacon was proven by the wrecks of three vessels in 1796, with in 16 lives were lost. The Marine Society sent a letter to Congress:

That much of the property and many of the lives of their fellow citizens are almost every year lost in coming into the harbour of Salem for want of proper lights to direct their course... This calamity can, in the opinion of this society be prevented only by erecting a lighthouse on the northern end of Bakers Island . . .

On April 8, 1796, President Washington signed a congressional appropriation of $6,000 for a lighthouse.

Benjamin Lincoln (1733-1810)

General Lincoln visited the site in June and expressed misgivings. There were already twin lights at Thacher Island to the north and Plymouth to the south, with as well as a single light at Boston Harbor in the middle and another single light in the planning stages at Cape Cod.

Lincoln worried that the light or lights at Baker’s Island could be confused with one of the other stations, so he proposed a two-story building with three lights arranged along a 50-foot span on its roof. This proposal was apparently regarded as impractical, and it was eventually agreed that two lights would be adequate at Baker’s Island.

Ten acres of land for the station were ceded to the federal government, and Solomon Blake, a contractor from Boston, constructed the lighthouse in 1797 for $3,674.57. The two lights went into service on January 3, 1798. Two towers were located on top of a two-story, wood-frame keeper’s house, about 40 feet apart at either end of the building. The south light was 95 feet above mean high water, and the north light was 78 feet high.

The first keeper was Captain George Chapman of the Salem Marine Society. He served until 1815, when he was about 75 years old. Chapman later became blind, a condition that was blamed on the brightness of the lighthouse lamps.

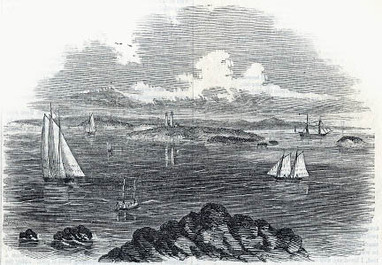

Salem’s peak as a port came in the late 1700s into the early 1800s, when as many as 10 ships unloaded each week at the city’s wharves. Vessels from Salem journeyed to far-flung ports in China, India, Japan, and Australia. On their the ships’ return, pilots stationed on Baker’s Island would board the incoming ships and navigate to the wharves.

Lincoln worried that the light or lights at Baker’s Island could be confused with one of the other stations, so he proposed a two-story building with three lights arranged along a 50-foot span on its roof. This proposal was apparently regarded as impractical, and it was eventually agreed that two lights would be adequate at Baker’s Island.

Ten acres of land for the station were ceded to the federal government, and Solomon Blake, a contractor from Boston, constructed the lighthouse in 1797 for $3,674.57. The two lights went into service on January 3, 1798. Two towers were located on top of a two-story, wood-frame keeper’s house, about 40 feet apart at either end of the building. The south light was 95 feet above mean high water, and the north light was 78 feet high.

The first keeper was Captain George Chapman of the Salem Marine Society. He served until 1815, when he was about 75 years old. Chapman later became blind, a condition that was blamed on the brightness of the lighthouse lamps.

Salem’s peak as a port came in the late 1700s into the early 1800s, when as many as 10 ships unloaded each week at the city’s wharves. Vessels from Salem journeyed to far-flung ports in China, India, Japan, and Australia. On their the ships’ return, pilots stationed on Baker’s Island would board the incoming ships and navigate to the wharves.

Joseph Perkins, who received a federal commission as a pilot in 1791, was on Baker’s Island during the War of 1812. One day he was alarmed to see the American frigate U.S.S. Constitution being pursued by a pair of British vessels. Perkins rowed out in his dory, boarded “Old Ironsides,” and deftly guided the frigate to the safety of Marblehead Harbor.

Former pilot Perkins succeeded Chapman as keeper in 1815. The Reverend Dr. William Bentley visited Perkins at the lighthouse in August 1817. He described the visit in his diary:

Captain Perkins has a garden enclosed, three cows, six pigs, and was cutting hay for the winter. Keeps rabbits and sheep. Has many conveniences about his house in a state much beyond what was formerly seen.

A “Notice to Mariners” issued by the Massachusetts lighthouse superintendent Henry A. S. Dearborn in late June 1816 announced that the lights would be extinguished for two months while the station was altered. In place of the two lights, there would be a single fixed light, three feet shorter than the lower of the two original lights.

During a snowstorm in the pre-dawn hours of February 24, 1817, the ship Union smashed into the island’s rocky shore with a cargo of pepper and tin, much of which was strewn on the beach. Mariners claimed that having only one light made it difficult for them to distinguish Baker’s Island from Boston Light, a fact that was proven by an increased number of wrecks, including that of the Union.

In 1820, the Salem Marine Society and the people of Salem, Marblehead, and Beverly petitioned the government for the return of a second light. The station was reverted to two lights in the summer and fall of 1820 after an appropriation of $9,000 (the sum included funds for a lighthouse at Ten Pound Island in Gloucester).

A new 59-foot conical stone tower and the refurbished shorter (26-foot), octagonal stone tower, both with octagonal iron lanterns, were lighted in October 1820. Somewhere along the line, the two towers—about 40 feet apart from each other—picked up the nickname of the “Ma and Pa” or “Mr. and Mrs.” lighthouses.

Captain Perkins has a garden enclosed, three cows, six pigs, and was cutting hay for the winter. Keeps rabbits and sheep. Has many conveniences about his house in a state much beyond what was formerly seen.

A “Notice to Mariners” issued by the Massachusetts lighthouse superintendent Henry A. S. Dearborn in late June 1816 announced that the lights would be extinguished for two months while the station was altered. In place of the two lights, there would be a single fixed light, three feet shorter than the lower of the two original lights.

During a snowstorm in the pre-dawn hours of February 24, 1817, the ship Union smashed into the island’s rocky shore with a cargo of pepper and tin, much of which was strewn on the beach. Mariners claimed that having only one light made it difficult for them to distinguish Baker’s Island from Boston Light, a fact that was proven by an increased number of wrecks, including that of the Union.

In 1820, the Salem Marine Society and the people of Salem, Marblehead, and Beverly petitioned the government for the return of a second light. The station was reverted to two lights in the summer and fall of 1820 after an appropriation of $9,000 (the sum included funds for a lighthouse at Ten Pound Island in Gloucester).

A new 59-foot conical stone tower and the refurbished shorter (26-foot), octagonal stone tower, both with octagonal iron lanterns, were lighted in October 1820. Somewhere along the line, the two towers—about 40 feet apart from each other—picked up the nickname of the “Ma and Pa” or “Mr. and Mrs.” lighthouses.

Near the end of March in 1825, Keeper Nathaniel Ward and his assistant, a Mr. Marshall, left the mainland in a small flat-bottomed boat laden with wood and other supplies, heading for the island. A storm and heavy seas prevented their safe return. Ward was later found dead on the shore of the island, and Marshall died in the boat. According to a newspaper account, Ward was 49 years old and left a large family “in indigent circumstances.”

Undated photo of the fog bell tower

Ambrose Martin followed Ward as keeper at a salary of $300 yearly, raised to $400 in 1829. Martin’s daughter Jane, who learned to help her father tend the station, later became keeper at Marblehead Light. Another of the keeper’s sons, Elbridge Gerry Martin, 13 years old at the time, made the local newspapers in November 1827 when he shot an eagle, with a wingspan of nearly seven feet, on the island. The bird was presented to the East India Museum in Salem.

In 1833, two sons of Keeper Martin were in a boat about 6 six miles east of the island when they saw what appeared to be a sea serpent of incredible length. This was during a period when sea serpent sightings along the New England coast were frequently front-page news. In this case, as the Martin brothers grew closer, it became plain that the “serpent” was actually a long chain of “blackfish”—pilot whales—that scattered when the boat grew too near. From a distance, they had resembled a single undulating creature with bunches on its back. The New Bedford Mercury asserted that this explanation would “to most minds put to rest conclusively the existence of the Sea Serpent.”

Martin was keeper when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited during his survey of 1842. At that time, the taller tower was equipped with 15 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, and the shorter tower had 10 lamps with 13-inch reflectors. Lewis described both towers as leaky and rotten, with and the interiors as plagued with ice in winter. Both towers, he said, required a thorough repair. The dwelling, according to Lewis, was “old and crazy” and uncomfortable in winter, and it needed to be replaced. Lewis stressed the importance of the station and praised Keeper Martin:

The double light here is . . . of high importance to a port where so many valuable ships annually enter and depart from, and should be maintained in the most perfect state of efficiency. Such, however, is far from being the case. No light-house of its class in Massachusetts is so poorly provided for in respect to the quality of the apparatus, which was old when introduced here, and now completely worn out. The keeper is deserving of the greatest praise for the extreme neatness and order of the whole establishment, which is second to none in this particular. A good apparatus, therefore, in such hands, would be well cared for, and is absolutely required in so important a locality; and seventeen winters’ residence in a house little better than a barn entitles a faithful public servant to a comfortable dwelling in his old age.

In 1833, two sons of Keeper Martin were in a boat about 6 six miles east of the island when they saw what appeared to be a sea serpent of incredible length. This was during a period when sea serpent sightings along the New England coast were frequently front-page news. In this case, as the Martin brothers grew closer, it became plain that the “serpent” was actually a long chain of “blackfish”—pilot whales—that scattered when the boat grew too near. From a distance, they had resembled a single undulating creature with bunches on its back. The New Bedford Mercury asserted that this explanation would “to most minds put to rest conclusively the existence of the Sea Serpent.”

Martin was keeper when the engineer I. W. P. Lewis visited during his survey of 1842. At that time, the taller tower was equipped with 15 lamps and 14-inch reflectors, and the shorter tower had 10 lamps with 13-inch reflectors. Lewis described both towers as leaky and rotten, with and the interiors as plagued with ice in winter. Both towers, he said, required a thorough repair. The dwelling, according to Lewis, was “old and crazy” and uncomfortable in winter, and it needed to be replaced. Lewis stressed the importance of the station and praised Keeper Martin:

The double light here is . . . of high importance to a port where so many valuable ships annually enter and depart from, and should be maintained in the most perfect state of efficiency. Such, however, is far from being the case. No light-house of its class in Massachusetts is so poorly provided for in respect to the quality of the apparatus, which was old when introduced here, and now completely worn out. The keeper is deserving of the greatest praise for the extreme neatness and order of the whole establishment, which is second to none in this particular. A good apparatus, therefore, in such hands, would be well cared for, and is absolutely required in so important a locality; and seventeen winters’ residence in a house little better than a barn entitles a faithful public servant to a comfortable dwelling in his old age.

New lanterns and Fresnel lenses were installed on both towers in 1857. A new one-and-one-half-story keeper’s house—which still stands, somewhat altered over the years—was built at about the same time. The towers were lined with brick around the same time.

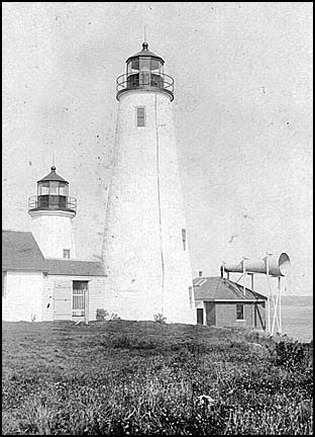

Baker's Island Twin Lights c. 1925 (U.S. Coast Guard)

A fog bell tower was erected sometime before 1868. A wood-frame assistant keeper’s house was added in 1873, and a new fog- bell tower replaced the original one in 1877. The year 1894 saw the addition of a brick oil house and a 122-foot boat slip.

The assistant keeper beginning in 1872 was Walter Scott Rogers of neighboring Beverly. When Rogers took the assistant position, he was in poor health and weighed only 101 pounds. He became the principal keeper in 1874, and life at the station apparently treated him well—he had gained 115 pounds by the time he left for West Chop Light on Martha’s Vineyard in 1881. He returned to Baker's Island in 1892 for another 11-year stint as keeper. In 1894, he recorded as many as 500 visitors to the light station in one day.

Rogers reported in February 1875 that the harbors of Salem and Beverly were frozen solid as far as Baker’s Island. When the ice broke up, it piled as high as 15 feet. In early March, Rogers wrote that “wild ducks from the ocean,” displaced by the ice, “sought shelter under the lee of the keeper’s house.” Rogers also experienced many bad storms during his stay, including the momentous Portland Gale of November 1898, which moved some of the nearby buoys from their positions.

During a particularly bad stretch of fog in October 1876, Baker’s Island’s fog bell was sounded for 72 straight hours. Later, there were often problems with the bell-striking mechanism, and the keepers sometimes had to strike the bell with a hand-held hammer.

The assistant keeper beginning in 1872 was Walter Scott Rogers of neighboring Beverly. When Rogers took the assistant position, he was in poor health and weighed only 101 pounds. He became the principal keeper in 1874, and life at the station apparently treated him well—he had gained 115 pounds by the time he left for West Chop Light on Martha’s Vineyard in 1881. He returned to Baker's Island in 1892 for another 11-year stint as keeper. In 1894, he recorded as many as 500 visitors to the light station in one day.

Rogers reported in February 1875 that the harbors of Salem and Beverly were frozen solid as far as Baker’s Island. When the ice broke up, it piled as high as 15 feet. In early March, Rogers wrote that “wild ducks from the ocean,” displaced by the ice, “sought shelter under the lee of the keeper’s house.” Rogers also experienced many bad storms during his stay, including the momentous Portland Gale of November 1898, which moved some of the nearby buoys from their positions.

During a particularly bad stretch of fog in October 1876, Baker’s Island’s fog bell was sounded for 72 straight hours. Later, there were often problems with the bell-striking mechanism, and the keepers sometimes had to strike the bell with a hand-held hammer.

In July 1879, a storm struck the area, and lightning destroyed the fog bell tower. The storm killed 30 people in the Boston Bay area. The bell tower was rebuilt in October and new striking machinery was installed.

The Winne-Egan Hotel

The Massachusetts Humane Society awarded Eugene Terpeny, an assistant keeper, a medal in 1894 for his role in saving the lives of the crew of the wrecked schooner Hero in October of that year. During a fierce storm, Terpeny and another man had launched a boat from the island and saved six men from the schooner, which was sinking fast.

The late 1800s were a time of change for the rest of the island. Dr. Nathan A. Morse of Salem bought the island, except for the lighthouse, in 1887.

In the following year, he opened a 75-room hotel called the Winne-Egan (said to be “beautiful expanse of water” in an Indian language).

The late 1800s were a time of change for the rest of the island. Dr. Nathan A. Morse of Salem bought the island, except for the lighthouse, in 1887.

In the following year, he opened a 75-room hotel called the Winne-Egan (said to be “beautiful expanse of water” in an Indian language).

The hotel was advertised as a “sure tonic for neurasthenia.” Healthful activities were stressed, including sailing, tennis, and fishing. Alcohol was banned. The Winne-Egan attracted as many as 1,000 guests in a summer.

The fog signal building and horn circa 1910

For a time, Keeper Rogers had a part-time job on the side, harvesting and cutting ice from the island’s pond to fill the hotel’s iceboxes. The Winne-Egan hotel burned down in 1906, and the island became the exclusive domain of the cottage owners.

For a number of years, regular boat service brought sightseers to Baker's Island. On the Fourth of July in 1898, the tour boat Surf City picked up a load of tourists on the island at 4:00 p.m. and returned to the mainland at Salem Willows, where some of the passengers disembarked. The rest stayed on board to go on to Salem's neighboring city, Beverly. A short time later a sudden squall rained large hailstones on the vessel, and high winds caused it to list. The boat quickly filled with water and overturned. The majority of the passengers survived the disaster, but eight women and children died. One of the crewmen of the Surf City received a lifesaving medal for his part in saving most of those on board.

For a number of years, regular boat service brought sightseers to Baker's Island. On the Fourth of July in 1898, the tour boat Surf City picked up a load of tourists on the island at 4:00 p.m. and returned to the mainland at Salem Willows, where some of the passengers disembarked. The rest stayed on board to go on to Salem's neighboring city, Beverly. A short time later a sudden squall rained large hailstones on the vessel, and high winds caused it to list. The boat quickly filled with water and overturned. The majority of the passengers survived the disaster, but eight women and children died. One of the crewmen of the Surf City received a lifesaving medal for his part in saving most of those on board.

Beginning in 1902, the Lighthouse Board pleaded with Congress for funds to install a powerful new fog signal to replace the station’s bell. The plea was repeated yearly until Congress appropriated $10,000 on June 30, 1906.

A powerful new siren replaced the old fog bell, officially going into service on July 12, 1907. A new brick building was added to house the related equipment, including two 20-horsepower oil engines.

A neighbor observed the reactions of a horse and cattle at the light station on the occasion of the first trial of the siren. Most of the animals high-tailed it for the other side of the island. A single cow, apparently enamored of the sound, mooed her rapturous reply until the siren ceased.

Right: The two lighthouses and foghorn circa early 1900s. Courtesy of Michel Forand.

The complaints of island residents after the new signal went into operation were vehement. In September 1907, officials of the Lighthouse Board cruised to the island to observe experiments designed to lower the volume on the island. Rear Admiral Adm. George C. Reiter, chairman of the Lighthouse Board, said he had no power to abolish the signal, but he would do what he could to lessen the impact forits effect on residents. Eventually, the signal was aimed at the sea through a megaphone, so that it was barely audible on the island.

A neighbor observed the reactions of a horse and cattle at the light station on the occasion of the first trial of the siren. Most of the animals high-tailed it for the other side of the island. A single cow, apparently enamored of the sound, mooed her rapturous reply until the siren ceased.

Right: The two lighthouses and foghorn circa early 1900s. Courtesy of Michel Forand.

The complaints of island residents after the new signal went into operation were vehement. In September 1907, officials of the Lighthouse Board cruised to the island to observe experiments designed to lower the volume on the island. Rear Admiral Adm. George C. Reiter, chairman of the Lighthouse Board, said he had no power to abolish the signal, but he would do what he could to lessen the impact forits effect on residents. Eventually, the signal was aimed at the sea through a megaphone, so that it was barely audible on the island.

|

Keeper Rogers retired to a farm in Rowley, Massachusetts, in October 1911. A newspaper story at the time of his retirement stated that Rogers had assisted in 21 wrecks during his years at Baker’s Island, and he had saved the lives of six men. He had furnished more than 400 meals for shipwrecked mariners.

Elliot Hadley, previously the first keeper of Graves Light in Boston Harbor, served as the principal keeper at Baker’s Island from 1911 to 1918. Hadley used a small horse-drawn vehicle to get around the island. His children were the last to attend school on the island, in a small building near the principal keeper’s house. Left: Keeper Walter Rogers |

During World War I, a Naval Reserve unit was stationed on the island to keep watch for German submarines. The men were quartered in a house near the light station, and, later, in the former schoolhouse on the station grounds.

The last civilian keeper on the island was Arthur L. Payne. Keeper Payne served from 1918 to 1943, the longest stint of any keeper in the station’s history. Payne also was appointed constable for the island in 1918, and he brought the first automotive transportation to the island—a Commerce truck in 1921, and later a Briscoe touring car.

Like the keepers before him, Payne kept a sharp eye out for vessels in trouble. Secretary of Commerce William C. Redfield officially commended Payne in August 1919 for going to the aid of two women whose boat had been wrecked, and for towing a disabled motorboat with eight passengers from a point three miles off Baker’s Island into the harbor at Manchester. In 1931, he was again commended, along with Assistant Keeper Ernest A. Sampson, for rescuing two men who were stranded on a rock after their boat was lost. Ten days after that, on April 20, Payne put out a grass fire that had gotten out of control at a cottage on the island.

Officials proposed the discontinuance of the smaller of the two lighthouses in 1922. In contrast to what had happened in 1816, nobody in the Salem area voiced any strong objections. The smaller lighthouse was discontinued on June 30, 1926. John Robinson, a mechanic at the lighthouse depot in Chelsea, Massachusetts, spent 10 days on the island overseeing the installation of new equipment in the taller tower. When the lens pedestal was removed, Keeper Payne found an 1847 penny that had been hidden beneath it.

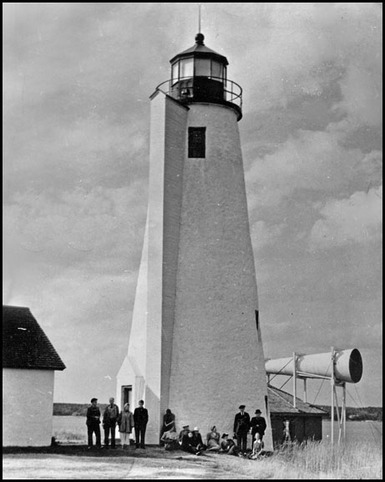

Above: This 1940 photo shows the foghorn as well as the structure on the side of the tower that held the weights that rotated the lens. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

Payne, called by Edward Rowe Snow a “brave, deserving lighthouse man who faithfully performed his duty to the end,” retired in 1943 and was followed by a succession of Coast Guard crews. After his retirement, Payne remained on the island and was elected president of the Baker’s Island Association in 1945.

The Coast Guard erected a lookout tower east of the lighthouse during World War II, and a detachment kept a constant watch for German submarines. The men began nightly patrols of the island’s shores, unaware of the presence of much poison ivy. Arthur Payne came to the rescue and treated the itchy Coast Guardsmen.

The fog siren remained in use until it was replaced by an air horn in 1959. In July 1967, the horn sounded for a record 324 hours and 20 minutes, or nearly half the month. One island resident said, “It doesn’t bother us because you get used to it.”

The Coast Guard stationed two keepers and their families on the island. In 1967, the only winter residents on the island were Coast Guard keeper Randall (Andy) Anderson, his wife, Lorraine, and their baby, along with Coast Guardsman John Krebs and his wife. “In the wintertime, you’re all alone, really alone,” said Krebs. “It’s awesome in a storm.” The only company the families had was “a lobsterman now and then.”

Like the keepers before him, Payne kept a sharp eye out for vessels in trouble. Secretary of Commerce William C. Redfield officially commended Payne in August 1919 for going to the aid of two women whose boat had been wrecked, and for towing a disabled motorboat with eight passengers from a point three miles off Baker’s Island into the harbor at Manchester. In 1931, he was again commended, along with Assistant Keeper Ernest A. Sampson, for rescuing two men who were stranded on a rock after their boat was lost. Ten days after that, on April 20, Payne put out a grass fire that had gotten out of control at a cottage on the island.

Officials proposed the discontinuance of the smaller of the two lighthouses in 1922. In contrast to what had happened in 1816, nobody in the Salem area voiced any strong objections. The smaller lighthouse was discontinued on June 30, 1926. John Robinson, a mechanic at the lighthouse depot in Chelsea, Massachusetts, spent 10 days on the island overseeing the installation of new equipment in the taller tower. When the lens pedestal was removed, Keeper Payne found an 1847 penny that had been hidden beneath it.

Above: This 1940 photo shows the foghorn as well as the structure on the side of the tower that held the weights that rotated the lens. From the collection of Edward Rowe Snow, courtesy of Dolly Bicknell.

Payne, called by Edward Rowe Snow a “brave, deserving lighthouse man who faithfully performed his duty to the end,” retired in 1943 and was followed by a succession of Coast Guard crews. After his retirement, Payne remained on the island and was elected president of the Baker’s Island Association in 1945.

The Coast Guard erected a lookout tower east of the lighthouse during World War II, and a detachment kept a constant watch for German submarines. The men began nightly patrols of the island’s shores, unaware of the presence of much poison ivy. Arthur Payne came to the rescue and treated the itchy Coast Guardsmen.

The fog siren remained in use until it was replaced by an air horn in 1959. In July 1967, the horn sounded for a record 324 hours and 20 minutes, or nearly half the month. One island resident said, “It doesn’t bother us because you get used to it.”

The Coast Guard stationed two keepers and their families on the island. In 1967, the only winter residents on the island were Coast Guard keeper Randall (Andy) Anderson, his wife, Lorraine, and their baby, along with Coast Guardsman John Krebs and his wife. “In the wintertime, you’re all alone, really alone,” said Krebs. “It’s awesome in a storm.” The only company the families had was “a lobsterman now and then.”

|

In February 2013, Andy Anderson recalled his time at Bakers Island:

In March of 1967 I, as a 22-year-old Third Class Petty Officer, was assigned as Officer in Charge (OinC) of Bakers Island Light Station. I was relieving David McKenzie. I, my 18-year-old wife Lorraine, and four-month-old daughter Rhonda arrived at the Homeowners pier via a Coast Guard buoy tender. The assistant keeper, John Krebs, met us with the station's tractor and trailer to transport us and our belongings to our new home. Lightstation OinCs are charged with all aspects of the maintenance and proper operation of the facilities. Alternating 12-hour periods (watches) are assigned to the keepers. At the end of each week, the watch would be switched from day to night. The watch stander is responsible for turning light on or off when required and fog signal operation during reduced visibility. Daily handwritten logs were maintained to document operation of equipment and maintenance performed. In all it was a lot of responsibility to be placed on very young Coasties. One of the requirements for this duty was family with no school age children, so most keepers were young. This was a chapter of my career that I will always cherish. |

Lorraine Anderson shared her memories:

My husband, Randall Anderson, and I were the last family lightkeepers at Bakers Island Light before it received a stag crew in preparation for automation. We were at Bakers for almost four years.

The day we moved out to the island, there were very choppy seas. It was a very round-hulled cutter so we rolled a lot. I was told to stay down under in the cabin with my four-month old daughter as it was risky to be on deck. So, for the one and only time in my life I got seasick. When we reached the island my head was throbbing mercilessly. The tractor on the pier took us to the highest point on the island and to my new home. Andy told me to go upstairs and lie down. I did, and then I heard it -- the fog signal, just yards from my bedroom window. I foolishly ran to the top of the stairs and told Andy to make it stop! You should have seen the look on his face, poor thing. But the human brain is an amazing thing. You quickly adjust, and it wasn't long till we would be talking and then stop and listen, satisfied that the fog signal was indeed doing its job.

As you can imagine, raising a family on what was technically a military base could sometimes be complicated. For instance, one time we were having an inspection by an officer dispatched from Boston headquarters, to make sure our floors were waxed and everything was in proper working condition. But my husband was cited a violation because he put a couple of drops of red paint into some white paint to make a pink nursery for my baby girl. But not to worry, he went on to have a wonderful career in the Coast Guard. He served 26 years and retired as a W-4.

We had a great relationship with the lobstermen (Andy watched out for their traps) and the summer residents of the island. Edward Rowe Snow (the "Flying Santa") dropped packages from his plane at Christmas, and one year the yacht club brought Santa Claus to the island by boat to see our baby girl.

The Gloucester search and rescue station was our support system; each keeper and his family got off the island for three consecutive days each month. Gloucester would send a 30-footer out to pick up a keeper and family and deliver mail, groceries, etc. On these days on the mainland we shopped the commissary, had doctor appointments and visited with family and friends. This was especially important in the winter when we were so isolated. But sometimes, the ocean would be just too rough to board, so we would have to postpone till the seas calmed down -- and this could go on for days or more.

Well, one day Gloucester called and said they would give it a try, even though it still was a little choppy. We were waiting on the pier. It was February and so cold. The wind picked up again and as the boat approached the pier the two young seaman expressed doubt about my ability to board. I was seven months pregnant with my second child and wearing a big furry jacket, so I probably looked as big as the boat to them. I had done this so many times before, so Andy jumped on board, held out his arms and reminded me as he always did, "Do not hesitate."

When the surf brought the boat to the pier, I jumped and we were on our way. Unfortunately, the weather that February was not going to cooperate with my getting on or off the island. While we were in Boston, we had a severe northeaster that left the city immobilized. Andy was needed back on the island of course (he was the engineer and kept all the machinery working) so they put him on a helicopter at Salem Air Station and took him back out to the island. It was deemed to be too dangerous for me to go along, so I did not get home for another week or so.

When the snow melted, I would put my daughter in her stroller (we purchased one with large rubber wheels to accommodate the terrain), bundle her up and walk around the island. Some of the residents would come out on the weekends in the spring. The Nicholsons (Mr. and Mrs.) would always invite us in for hot chocolate. We would sit in front of the wood-burning fireplace and watch the surf hit the rocky shore and just talk. They were an elderly couple, but the age difference was of no matter.

The island came to life when the summer families arrived. The island took on a whole new feel. Andy would help with the tractor and trailer. Of course, with Andy being an engineer, there was always a question about a generator that did not work or a lawnmower or water pump, etc. So we coexisted very well. It was actually a good thing for the residents because the station had a helipad and in an emergency Salem Air could have a helicopter on the island in about five minutes.

But at the end of the day, 24 hours a day, it was about the light. The keepers stood 12-hour watches to make sure the light was operating properly and that the fog signal was turned on when needed. And yes, this was done manually. We were always aware of the weather. I could be doing dishes and looking out the window and see the fog start to roll in and dry my hands and walk down to the engine room just to see if the on duty keeper was aware. Andy's eyes were always on the sea. He would alert the lobstermen of poachers. Quite often we would get a call to check the pier and, of course, a bushel of lobsters would mysteriously appear. He would alert the Gloucester station if a craft appeared to be in need of assistance.

My husband, Randall Anderson, and I were the last family lightkeepers at Bakers Island Light before it received a stag crew in preparation for automation. We were at Bakers for almost four years.

The day we moved out to the island, there were very choppy seas. It was a very round-hulled cutter so we rolled a lot. I was told to stay down under in the cabin with my four-month old daughter as it was risky to be on deck. So, for the one and only time in my life I got seasick. When we reached the island my head was throbbing mercilessly. The tractor on the pier took us to the highest point on the island and to my new home. Andy told me to go upstairs and lie down. I did, and then I heard it -- the fog signal, just yards from my bedroom window. I foolishly ran to the top of the stairs and told Andy to make it stop! You should have seen the look on his face, poor thing. But the human brain is an amazing thing. You quickly adjust, and it wasn't long till we would be talking and then stop and listen, satisfied that the fog signal was indeed doing its job.

As you can imagine, raising a family on what was technically a military base could sometimes be complicated. For instance, one time we were having an inspection by an officer dispatched from Boston headquarters, to make sure our floors were waxed and everything was in proper working condition. But my husband was cited a violation because he put a couple of drops of red paint into some white paint to make a pink nursery for my baby girl. But not to worry, he went on to have a wonderful career in the Coast Guard. He served 26 years and retired as a W-4.

We had a great relationship with the lobstermen (Andy watched out for their traps) and the summer residents of the island. Edward Rowe Snow (the "Flying Santa") dropped packages from his plane at Christmas, and one year the yacht club brought Santa Claus to the island by boat to see our baby girl.

The Gloucester search and rescue station was our support system; each keeper and his family got off the island for three consecutive days each month. Gloucester would send a 30-footer out to pick up a keeper and family and deliver mail, groceries, etc. On these days on the mainland we shopped the commissary, had doctor appointments and visited with family and friends. This was especially important in the winter when we were so isolated. But sometimes, the ocean would be just too rough to board, so we would have to postpone till the seas calmed down -- and this could go on for days or more.

Well, one day Gloucester called and said they would give it a try, even though it still was a little choppy. We were waiting on the pier. It was February and so cold. The wind picked up again and as the boat approached the pier the two young seaman expressed doubt about my ability to board. I was seven months pregnant with my second child and wearing a big furry jacket, so I probably looked as big as the boat to them. I had done this so many times before, so Andy jumped on board, held out his arms and reminded me as he always did, "Do not hesitate."

When the surf brought the boat to the pier, I jumped and we were on our way. Unfortunately, the weather that February was not going to cooperate with my getting on or off the island. While we were in Boston, we had a severe northeaster that left the city immobilized. Andy was needed back on the island of course (he was the engineer and kept all the machinery working) so they put him on a helicopter at Salem Air Station and took him back out to the island. It was deemed to be too dangerous for me to go along, so I did not get home for another week or so.

When the snow melted, I would put my daughter in her stroller (we purchased one with large rubber wheels to accommodate the terrain), bundle her up and walk around the island. Some of the residents would come out on the weekends in the spring. The Nicholsons (Mr. and Mrs.) would always invite us in for hot chocolate. We would sit in front of the wood-burning fireplace and watch the surf hit the rocky shore and just talk. They were an elderly couple, but the age difference was of no matter.

The island came to life when the summer families arrived. The island took on a whole new feel. Andy would help with the tractor and trailer. Of course, with Andy being an engineer, there was always a question about a generator that did not work or a lawnmower or water pump, etc. So we coexisted very well. It was actually a good thing for the residents because the station had a helipad and in an emergency Salem Air could have a helicopter on the island in about five minutes.

But at the end of the day, 24 hours a day, it was about the light. The keepers stood 12-hour watches to make sure the light was operating properly and that the fog signal was turned on when needed. And yes, this was done manually. We were always aware of the weather. I could be doing dishes and looking out the window and see the fog start to roll in and dry my hands and walk down to the engine room just to see if the on duty keeper was aware. Andy's eyes were always on the sea. He would alert the lobstermen of poachers. Quite often we would get a call to check the pier and, of course, a bushel of lobsters would mysteriously appear. He would alert the Gloucester station if a craft appeared to be in need of assistance.

|

The light, which was converted to kerosene in 1878 and then to electric operation in 1938, was automated in 1972. A Coast Guard crew arrived to remove the Fresnel lens, which floated on a bed of mercury, as part of the automation process. They were overcome by mercury fumes and had to be removed by helicopter. The lens is now on display at the Maine Lighthouse Museum in Rockland, Maine.

In the clip to the right, circa 1989, Ken Black, director of the Shore Village Museum in Rockland, Maine, explains the fourth-order Fresnel lens that had been removed from Baker's Island Light. |

|

In 1993, the Coast Guard made repairs to the lantern and the generator house. Three years later, a $250,000 restoration project began.

The contractor hired by the Coast Guard, Marty Nally, found that some stones from near the top of the tower had fallen out, and that the foundation was found to be nearly crumbling. A Coast Guard architect, Marsha Levy, who formulated the plans for the restoration, said that the lighthouse’s construction is more sophisticated than most built around the same time. Nally and his crew used mortar similar to what was used when the tower was first built, and the exterior was coated with a rough stucco material that accentuates the bumpy stone construction.

In the summer of 2000, the Coast Guard solarized the light. At the same time they renovated the fog signal building. The brick was removed from the sealed windows and replaced with glass. The fog signal was removed from the top of the building and was placed on an adjacent concrete pad.

Left: Solar panels provide power for the light.

In the summer of 2000, the Coast Guard solarized the light. At the same time they renovated the fog signal building. The brick was removed from the sealed windows and replaced with glass. The fog signal was removed from the top of the building and was placed on an adjacent concrete pad.

Left: Solar panels provide power for the light.

There have been claims that some of the homes on the island, as well as the light station, are haunted.

The stairs in the tower

Andy Jerome, caretaker for the Baker's Island Association from 1983 to 1987, reported that the foghorn would start for no apparent reason on clear nights. He sometimes had to get out of bed in the middle of the night to turn it off. The Coast Guard checked and could find nothing wrong. Jerome’s wife, Ruth, said she sensed a “presence” around the fog signal building. She was convinced the station was haunted, even though she previously didn’t believe in ghosts.

A team of paranormal investigators once ventured to the island with modern electronic equipment to record the presence of ghosts. They weren’t aware that there’s no electricity on the island—their investigation couldn’t even get started.

A team of paranormal investigators once ventured to the island with modern electronic equipment to record the presence of ghosts. They weren’t aware that there’s no electricity on the island—their investigation couldn’t even get started.

In 1988, the Baker’s Island Association, which manages the island, was granted a license to use and preserve the two keeper’s’ residences. In 2002, under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000, the light station was made available to a qualified new owner.

View from the top

In late April 2005, it was announced that U.S. Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton had recommended that ownership be transferred to the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC). A committee of the National Park Service (NPS) had chosen the ENHC as the most qualified applicant. The only other applicant was the Baker's Island Lighthouse Preservation Society, Inc. (BILPS), made up of island residents. BILPS challenged the decision of the NPS in court, but a federal judge upheld the original decision in late October 2006.

In late 2010, a $250,000 grant was awarded for a landing craft-style boat (below) to access the island. There are now public tours in summer, with trips aboard Naumkeag from early July to early September. Click here for details.

In late 2010, a $250,000 grant was awarded for a landing craft-style boat (below) to access the island. There are now public tours in summer, with trips aboard Naumkeag from early July to early September. Click here for details.

Listen to an interview with Annie C. Harris of Essex Heritage on the podcast "Light Hearted":

The lighthouse can also be seen from shore from points in Salem, Marblehead, and Manchester-by-the-Sea.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

George Chapman (1798-1815); Joseph Perkins (1815-182?); Nathaniel Ward (?-1825, died on duty); Ambrose Martin (1825?-1843); Joseph G. Martin (1843-?); Daniel Norwood (?); Robert Peal (?); ? Russell (?-1861); Charles J. Williams (1861-1871); George Hobbs (1871-1874); Walter S. Rogers, assistant (1872-1874), then keeper (1874-1881, 1892-1911); James F. Lundgren, assistant, (1878-1881), then keeper (1881-1892); Eugene Terpeny (assistant, c.1893-1894), Elliott Hadley (1911-1918); Arthur L. Payne (1918-1943); Ernest A. Sampson, assistant (1929-1941); Benjamin E. Stewart (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1946-1951); Red Dawson (Coast Guard, ?); Bob Johnson (Coast Guard, ?); Clifford Willis (Coast Guard, ?); Leonard Mullen (Coast Guard, ?); Paul Guy (Coast Guard, ?); Paul Black (Coast Guard, ?); Andrew M. McLaughlin (Coast Guard Third Class Engineman, February 1956 - July 1956); Richard J. LaLonde (Coast Guard, First Class Engineman, c. 1956); Tex Blanchard (Coast Guard, ?); Allen C. Farrell (Coast Guard, ?); Gerald E. Ryan (Coast Guard, ?); Roger L. Lamascus (Coast Guard assistant, 1962-1965); Donald G. Trecartin (Coast Guard officer in charge 1962-1965); David McKenzie (Coast Guard officer in charge March 1967-April 1968) Randall K. Anderson (Coast Guard officer in charge March 1967-April 1968 and September 1968-December 1969); David Rollins (Coast Guard officer in charge April 1968-September 1968); John Krebs (Coast Guard assistant, 1965-April 1968); R. Royston (Coast Guard assistant September 1968-March 1969); Paul Driscoll (Coast Guard assistant, March 1969-1971); Harry D. Toler (Coast Guard officer in charge, December 1969-?)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

George Chapman (1798-1815); Joseph Perkins (1815-182?); Nathaniel Ward (?-1825, died on duty); Ambrose Martin (1825?-1843); Joseph G. Martin (1843-?); Daniel Norwood (?); Robert Peal (?); ? Russell (?-1861); Charles J. Williams (1861-1871); George Hobbs (1871-1874); Walter S. Rogers, assistant (1872-1874), then keeper (1874-1881, 1892-1911); James F. Lundgren, assistant, (1878-1881), then keeper (1881-1892); Eugene Terpeny (assistant, c.1893-1894), Elliott Hadley (1911-1918); Arthur L. Payne (1918-1943); Ernest A. Sampson, assistant (1929-1941); Benjamin E. Stewart (Coast Guard, c. 1940s); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1946-1951); Red Dawson (Coast Guard, ?); Bob Johnson (Coast Guard, ?); Clifford Willis (Coast Guard, ?); Leonard Mullen (Coast Guard, ?); Paul Guy (Coast Guard, ?); Paul Black (Coast Guard, ?); Andrew M. McLaughlin (Coast Guard Third Class Engineman, February 1956 - July 1956); Richard J. LaLonde (Coast Guard, First Class Engineman, c. 1956); Tex Blanchard (Coast Guard, ?); Allen C. Farrell (Coast Guard, ?); Gerald E. Ryan (Coast Guard, ?); Roger L. Lamascus (Coast Guard assistant, 1962-1965); Donald G. Trecartin (Coast Guard officer in charge 1962-1965); David McKenzie (Coast Guard officer in charge March 1967-April 1968) Randall K. Anderson (Coast Guard officer in charge March 1967-April 1968 and September 1968-December 1969); David Rollins (Coast Guard officer in charge April 1968-September 1968); John Krebs (Coast Guard assistant, 1965-April 1968); R. Royston (Coast Guard assistant September 1968-March 1969); Paul Driscoll (Coast Guard assistant, March 1969-1971); Harry D. Toler (Coast Guard officer in charge, December 1969-?)