History of Watch Hill Lighthouse, Westerly, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Watch Hill, a village of Westerly, Rhode Island, is a quaint resort area with an old carousel and many shops and stately mansions. Clark Gable, Groucho Marx, Henry Ford, and Douglas Fairbanks were among those who vacationed here.

A watchtower and a simple beacon were first established at Watch Hill by the Rhode Island colonial government around 1745, giving the area its name, and earlier the point may have been used as a lookout by the Narragansett Indians. The watchtower and beacon were destroyed in a 1781 storm.

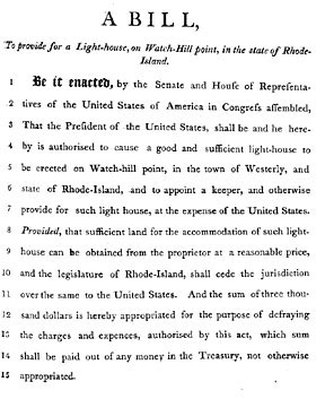

Discussion of a lighthouse to mark the eastern entrance to Fishers Island Sound, and to warn mariners of a dangerous reef southwest of Watch Hill, began in 1793. An act to build the lighthouse was signed in 1806 by President Thomas Jefferson. The government purchased four acres of land for $500 from George and Thankful Foster, and the lighthouse, Rhode Island's second after Beavertail, was completed in early 1808.

Discussion of a lighthouse to mark the eastern entrance to Fishers Island Sound, and to warn mariners of a dangerous reef southwest of Watch Hill, began in 1793. An act to build the lighthouse was signed in 1806 by President Thomas Jefferson. The government purchased four acres of land for $500 from George and Thankful Foster, and the lighthouse, Rhode Island's second after Beavertail, was completed in early 1808.

The first Watch Hill Light was a 35-foot round wooden tower with ten whale oil lamps and parabolic reflectors.

In 1827 the light was made a rotating one in an effort to differentiate it from the light at Stonington, Connecticut. An 1837 survey by E. Blunt and G.W. Blunt reported, "The light at Watch Hill is a very bad one, the lamps are bad, the reflectors too small... Also the machinery for this light is so bad that... it sometimes requires being turned by hand."

The first keeper, Jonathan Nash, served 27 years at Watch Hill, losing his job in 1834 for political reasons. Nash, whose initial salary was $200 per year, recorded 45 vessels wrecked in the vicinity during his years as keeper. Jonathan Nash and his son-in-law later built the first hotel at Watch Hill.

The first tower served until 1855, when erosion necessitated the building of a new tower farther back from the edge of the bluff. The new 45-foot square granite tower, lined with brick, was fitted with a fourth order Fresnel lens.

It was first lighted on February 1, 1856, and exhibited a fixed white light. A two story brick keeper's house, attached to the tower, was built the same year, and a granite sea wall was built around the perimeter of the lighthouse property.

The first keeper, Jonathan Nash, served 27 years at Watch Hill, losing his job in 1834 for political reasons. Nash, whose initial salary was $200 per year, recorded 45 vessels wrecked in the vicinity during his years as keeper. Jonathan Nash and his son-in-law later built the first hotel at Watch Hill.

The first tower served until 1855, when erosion necessitated the building of a new tower farther back from the edge of the bluff. The new 45-foot square granite tower, lined with brick, was fitted with a fourth order Fresnel lens.

It was first lighted on February 1, 1856, and exhibited a fixed white light. A two story brick keeper's house, attached to the tower, was built the same year, and a granite sea wall was built around the perimeter of the lighthouse property.

One of the worst maritime disasters in the vicinity of Watch Hill was the wreck of the steamer Metis in 1872.

The ship, carrying 160 people to Providence, collided with a schooner. At first it was not believed that the damage was bad enough to prevent the vessel from continuing, but about a mile from Watch Hill the Metis began to sink fast. Local residents managed to save 33 people, but the other 130 on board perished. A few years later a U.S. Life Saving Service Station was established at Watch Hill, close to the lighthouse. The station was abandoned in the 1940s and was destroyed in 1963.

Right: Robert Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, Photography Collection, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints & Photographs, The New York Public Library.

Right: Robert Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, Photography Collection, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints & Photographs, The New York Public Library.

In 1879, Sally Ann Crandall became the first woman to keep the light at Watch Hill, taking over for her husband following his death.

Keeper Crandall's salary was $500 per year. Fanny K. Sckuyler became the second woman keeper when she took over for Sally Ann Crandall in 1888.

In 1907 one of the most famous of all New England shipping disasters occurred four miles southwest of Watch Hill Light when the steamer Larchmont collided with a schooner in a February blizzard. Close to 200 people died in the disaster.

There was severe damage at the lighthouse during the hurricane of September 21, 1938, the worst storm in New England's recorded history. Many people died in the Westerly area during the storm.

The keeper reported that waves broke over the top of the lighthouse, smashing the lantern glass, damaging the lamp and sending seawater into the tower.

Left: Circa 1905. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, 5240

In 1907 one of the most famous of all New England shipping disasters occurred four miles southwest of Watch Hill Light when the steamer Larchmont collided with a schooner in a February blizzard. Close to 200 people died in the disaster.

There was severe damage at the lighthouse during the hurricane of September 21, 1938, the worst storm in New England's recorded history. Many people died in the Westerly area during the storm.

The keeper reported that waves broke over the top of the lighthouse, smashing the lantern glass, damaging the lamp and sending seawater into the tower.

Left: Circa 1905. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, 5240

Keeper Lawrence Congdon and Assistant Keeper Richard Fricke weathered the storm, but it took a few weeks to get Watch Hill Light operating again.

Another hurricane, named Carol, barreled up the coast and struck Rhode Island on August 31, 1954. Bill Mack, assistant keeper for the Coast Guard at the time, recalls that when the hurricane hit during the morning of August 31, he went to the fog signal building to get the foghorn going.

Waves were throwing stones "the size of baseballs" into the building, breaking the windows. Mack retreated to the keeper's house and remained there for the duration of the storm.

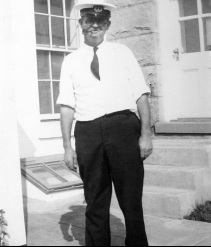

Right: Keeper Lawrence Congdon. Courtesy of Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association

Waves were throwing stones "the size of baseballs" into the building, breaking the windows. Mack retreated to the keeper's house and remained there for the duration of the storm.

Right: Keeper Lawrence Congdon. Courtesy of Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association

The waves were so high that virtually nothing could be seen from the house's east facing windows.

When the eye of the hurricane passed over, says Bill's wife, Carol, it looked like there was a riptide in the middle of the backyard.

As had happened in 1938, Watch Hill Point became an island through much of the hurricane. The road to the point was badly torn up and the east bank near the lighthouse was eaten away, practically undermining the fog signal building. All in all, about $125,000 worth of damage was sustained at the light station. The Macks left Watch Hill shortly after the hurricane, in October 1954.

Left: This photo of Carol and Bill Mack, about to leave the lighthouse for church with baby daughter Kathy, was taken by a visiting tourist.

As had happened in 1938, Watch Hill Point became an island through much of the hurricane. The road to the point was badly torn up and the east bank near the lighthouse was eaten away, practically undermining the fog signal building. All in all, about $125,000 worth of damage was sustained at the light station. The Macks left Watch Hill shortly after the hurricane, in October 1954.

Left: This photo of Carol and Bill Mack, about to leave the lighthouse for church with baby daughter Kathy, was taken by a visiting tourist.

William Ivan Clark was in charge beginning in 1959. At the time of his death in 1970, Clark was considered one of the last civilian lighthouse keepers in the United States.

In early January 1962, Clark was notified by a crewman at the nearby Coast Guard station that a ship had landed in the light station’s “front yard.” The huge Norwegian freighter Leif Viking had run aground on Gangway Rock, about 250 yards from the station.

A Coast Guard buoy tender helped to aid the vessel, which remained stranded for nine days before a tug towed it to New York City. The freighter was carrying 700 tons of paper.

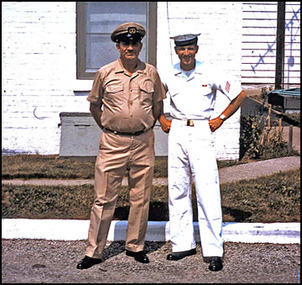

Right: Keeper William I. Clark, left, and Coast Guardsman John Carter. Courtesy of John Carter.

The light was automated in 1986 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern optic. After automation the lighthouse and other buildings were leased to the Watch Hill Lightkeepers Association. The association has established an endowment fund for the upkeep of the station.

A Coast Guard buoy tender helped to aid the vessel, which remained stranded for nine days before a tug towed it to New York City. The freighter was carrying 700 tons of paper.

Right: Keeper William I. Clark, left, and Coast Guardsman John Carter. Courtesy of John Carter.

The light was automated in 1986 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern optic. After automation the lighthouse and other buildings were leased to the Watch Hill Lightkeepers Association. The association has established an endowment fund for the upkeep of the station.

John A. Wilk, Sr., was the Coast Guard's officer in charge at the station from 1969 to 1974. His daughter, Rosemarie Kingsbury, wrote the following in 2007:

U.S. Coast Guard

I have recounted the stories to my children of how my brothers and I would walk up that metal spiral staircase, open the hatch, and on cold days or nights turn on the space heater, then wind the weight up to the top to keep the light going (the alarm was never to go off and if it ever did everyone who heard it immediately raced to the tower to wind the light). How we would go into the generator room to turn on the fog horn, run on the rocks, and give tours of the light to tourists. I have shown them how waves would break over the sea wall and run to the other side of the road on that narrow strip of land just outside the gate, where Mr. Butler kept his boat and small dock, trapping us at the Light.

I told them of how my father put an intercom at the gate and how he used it to scare my mother one evening (his idea but we all laughed); of my father and a relief watchman putting up the storm warning flags and the relief watchman being lifted off the ground by the wind; of how the eye of an almost hurricane come right over the point and we were able to go outside and look up; and much more.

Of all the places that we have lived, New Orleans, Mobile, Galveston, Chicopee, Buffalo, and more, the Watch Hill Lighthouse is the only place that I get homesick for. It is the one with the most memories and the place I love to visit the most.

A small museum in one of the station's buildings is open limited hours in the summer. Donations for the lighthouse's preservation are welcomed. Watch Hill Light continues to serve as an active aid to navigation.

For more information contact Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Jonathan Nash (1808-1833); Enoch Vose (1833-1841); Gilbert Pendleton (1841-1847); Daniel Babcock (1847-1849); Ethan Pendelton (1849-1853); Nelson Brown (1853-1861); Daniel Larkin (1861-1868); Jared S. Crandall (1868-1879, died in service); Sally Ann Crandall (1879-1888); Fanny K.Sckuyler (1888-1890); Joseph T. Fowler (1890-1895); Julius B. Young (1895-1910); Henry Burkhart (1910-1918); Thomas Murphy (1st asst., 1910-1914); James Gregory (1st asst., 1914-1918, head keeper 1918-1921); Willis A. Green (c. 1921); Sylvester Kenzia (1st asst., 1919-1923); John F. Anderson (1922-1924); Amos Broadmeadow (c. 1920s); Carl F. Anderson (1st asst., 1925-1931); Lawrence Congdon (March 1, 1924-1941); Frank Laftib (1st assistant 1931-1935); Richard Frick, assistant (1935-1941); Ernest A. Sampson (1944-1947); William H. Mack (Coast Guard, 1953-1954); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1955); William Ivan Clark (1959-1970); John Anthony Wilk (Coast Guard, 1969-1974); Jerry Pie (Coast Guard, c. 1978); Keith Hamlin (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1978); Rusty Merritt (Coast Guard, 1984-1986), Tony Methot (Coast Guard, 1983-1986)

I told them of how my father put an intercom at the gate and how he used it to scare my mother one evening (his idea but we all laughed); of my father and a relief watchman putting up the storm warning flags and the relief watchman being lifted off the ground by the wind; of how the eye of an almost hurricane come right over the point and we were able to go outside and look up; and much more.

Of all the places that we have lived, New Orleans, Mobile, Galveston, Chicopee, Buffalo, and more, the Watch Hill Lighthouse is the only place that I get homesick for. It is the one with the most memories and the place I love to visit the most.

A small museum in one of the station's buildings is open limited hours in the summer. Donations for the lighthouse's preservation are welcomed. Watch Hill Light continues to serve as an active aid to navigation.

For more information contact Watch Hill Lighthouse Keepers Association.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Jonathan Nash (1808-1833); Enoch Vose (1833-1841); Gilbert Pendleton (1841-1847); Daniel Babcock (1847-1849); Ethan Pendelton (1849-1853); Nelson Brown (1853-1861); Daniel Larkin (1861-1868); Jared S. Crandall (1868-1879, died in service); Sally Ann Crandall (1879-1888); Fanny K.Sckuyler (1888-1890); Joseph T. Fowler (1890-1895); Julius B. Young (1895-1910); Henry Burkhart (1910-1918); Thomas Murphy (1st asst., 1910-1914); James Gregory (1st asst., 1914-1918, head keeper 1918-1921); Willis A. Green (c. 1921); Sylvester Kenzia (1st asst., 1919-1923); John F. Anderson (1922-1924); Amos Broadmeadow (c. 1920s); Carl F. Anderson (1st asst., 1925-1931); Lawrence Congdon (March 1, 1924-1941); Frank Laftib (1st assistant 1931-1935); Richard Frick, assistant (1935-1941); Ernest A. Sampson (1944-1947); William H. Mack (Coast Guard, 1953-1954); Paul Baptiste (Coast Guard, 1955); William Ivan Clark (1959-1970); John Anthony Wilk (Coast Guard, 1969-1974); Jerry Pie (Coast Guard, c. 1978); Keith Hamlin (Coast Guard assistant, c. 1978); Rusty Merritt (Coast Guard, 1984-1986), Tony Methot (Coast Guard, 1983-1986)