History of Great Duck Island Light, near Frenchboro, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Great Duck Island got its name in the 1700s from a pond in its center that attracted large flocks of ducks each spring. William Gilley purchased the island, more than 200 acres in size and about nine miles south of Mount Desert Island, in 1837, and Charles Harding became the owner in 1867. The Gilley-Harding homestead on the northern side of the island burned down in 1882.

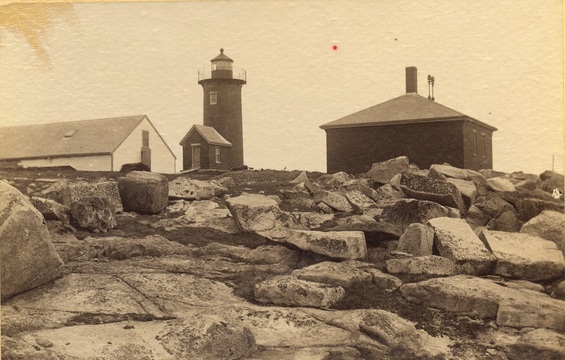

Circa late 1800s (National Archives).

There was discussion of establishing a lighthouse on the island as early as 1823 to aid mariners heading for the Mount Desert area and Blue Hill Bay from the south, but many decades would pass before the idea became reality. The Lighthouse Board recommended a light station on the island in 1885:

A light-house and fog-signal here would be of great aid to commerce going to, from, or past this portion of the coast of Maine, to guide vessels caught in easterly gales, and the usually accompanying snowstorms, into Bass Harbor or Southwest Harbor. Both are frequently used by coasting vessels at all seasons as harbors of refuge. It is especially essential that a fog-signal should be established here, as the fog-signals nearest, on either side, are those at Matinicus Rock and Petit Manan, which are 60 miles apart.

For a “proper light and fog-signal,” the Lighthouse Board requested a congressional appropriation of $10,000. The request was repeated in 1888, with an increase in the estimated cost to $30,000. The funds were appropriated in early 1889, and the government soon secured title to about 11 acres of land on the south side of the island.

Before the station could be constructed, a lumber schooner from Lubec, Maine, was wrecked on the island in a snowstorm in January 1890. Three crewmen died in the disaster. The bodies were found frozen together in death. The sailors were buried on the island; picks had to be used to dig the grave in the icy ground. Later, the keepers at the station honored the unknown sailors by placing a wreath on the grave each Memorial Day.

A light-house and fog-signal here would be of great aid to commerce going to, from, or past this portion of the coast of Maine, to guide vessels caught in easterly gales, and the usually accompanying snowstorms, into Bass Harbor or Southwest Harbor. Both are frequently used by coasting vessels at all seasons as harbors of refuge. It is especially essential that a fog-signal should be established here, as the fog-signals nearest, on either side, are those at Matinicus Rock and Petit Manan, which are 60 miles apart.

For a “proper light and fog-signal,” the Lighthouse Board requested a congressional appropriation of $10,000. The request was repeated in 1888, with an increase in the estimated cost to $30,000. The funds were appropriated in early 1889, and the government soon secured title to about 11 acres of land on the south side of the island.

Before the station could be constructed, a lumber schooner from Lubec, Maine, was wrecked on the island in a snowstorm in January 1890. Three crewmen died in the disaster. The bodies were found frozen together in death. The sailors were buried on the island; picks had to be used to dig the grave in the icy ground. Later, the keepers at the station honored the unknown sailors by placing a wreath on the grave each Memorial Day.

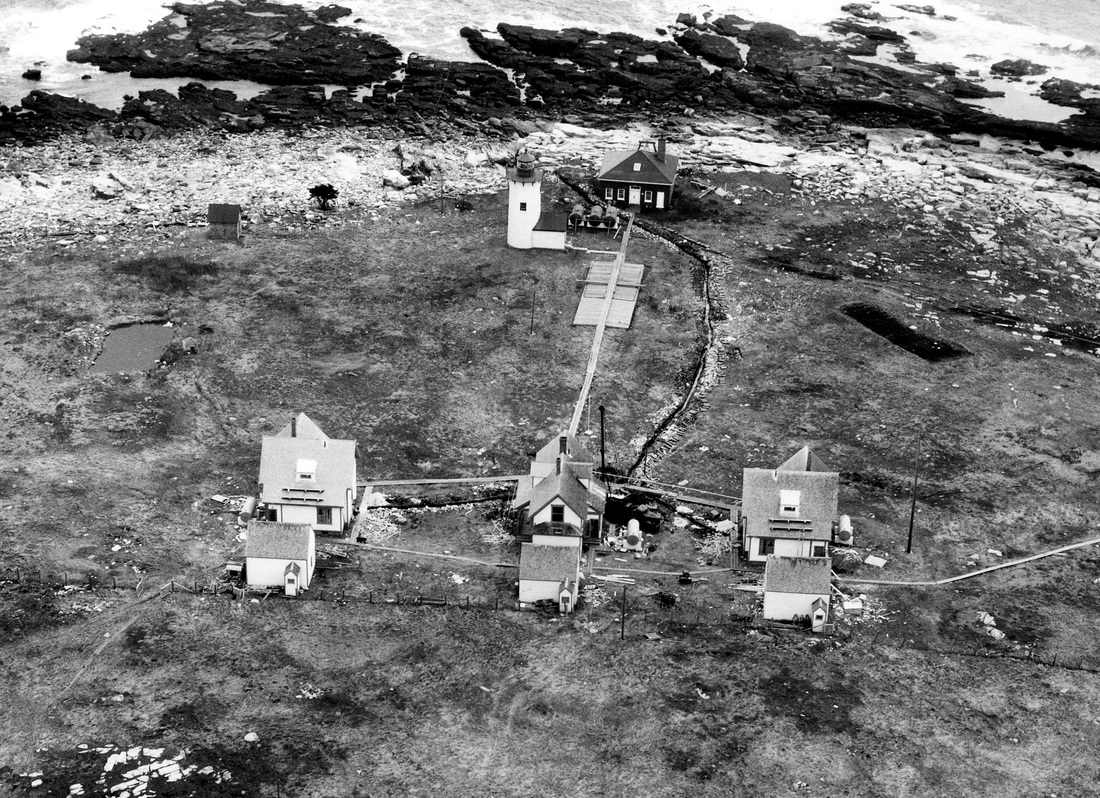

Work on the station began in May 1890. A double boat slip and boathouse were constructed on the east side of the island, joined to the lighthouse site by a 2,251-foot-long road. A 20-by-30-foot barn was erected at the lighthouse site to serve as temporary quarters for the workmen. Construction was completed by the end of the year, and the light was established on December 31, 1890. The first principal keeper was William F. Stanley.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

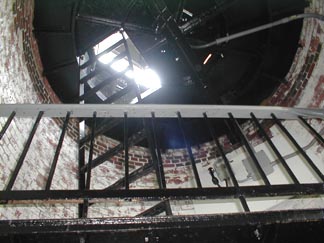

The lantern on the 42-foot cylindrical brick lighthouse originally held a fifth-order Fresnel lens. A brick service room was attached to the base of the tower, which was painted red until it was changed to white in the spring of 1900.

Three keepers’ dwellings of six rooms each were built side by side near the lighthouse, along with; outbuildings and a brick fog signal building with a steam-operated horn were erected as well. A 1,200-pound bell was provided as backup. An oil house was added in 1901.

In 1902, the original lens was replaced by a fourth-order lens. Many other improvements to the station were made in the 1902-1906 period, including the addition of a tramway from the landing to the fog signal building.

Keeper William Stanley and his wife had three children. Their son, Lyford Stanley, who was two weeks old when the family arrived on the island, later worked as a lobster boat builder in Bass Harbor for more than 50 years. He told the Bangor Daily News about the difficult way of life on Great Duck Island. He recalled that supplies were delivered to the opposite side of the island and were carried by wheelbarrow to the keeper's house. He described one foggy period when the foghorn blew for 13 straight days. "It was noisy down there," he said.

The state provided no school for the island until 1902, when Nathan Adam "Ad" Reed arrived as an assistant keeper. Reed came to the island with his wife, Emma, and their 16 children. The Reeds were probably the largest family in American lighthouse history. One of the Reeds' older daughters, Rena, eventually got a teaching certificate in Castine and was able to teach her younger siblings in the tiny schoolroom.

An often-repeated story concerns a dog that survived a shipwreck and swam to Great Duck Island. The dog was adopted by a girl who lived with her parents at the north end of the island and named Seaboy. Two years later the dog's owner, a fisherman, unexpectedly appeared to claim his pet. As the man was about to leave with Seaboy in his dory, the dog heard the girl call to him. He ran back to the girl as the fisherman rowed away, never to return.

The story of Seaboy, told in great detail by Robert Thayer Sterling in his book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, inspired a popular children's book, Captain's Castaway by Angeli Perrow and Emily Harris. Sterling was an assistant keeper at Great Duck Island for two years, and he professed a "particular fondness for this fine old station."

Andrew H. Kennedy was the principal keeper for several years in the 1930s. In September 1931, Kennedy and assistant keepers Earle Benson and Leverett Stanley went to the aid of the fishing schooner Rita A. Viator, which had grounded near the station during the night in heavy seas. The keepers rescued the captain and crew safely, and were honored for their efforts by special letters of commendation from Secretary of Commerce Robert P. Lamont.

James Freeman became keeper in 1940; he had previously been at Petit Manan Light. His daughter, Mazie Freeman Anderson, later wrote about a stormy night when her mother, Iva Freeman, became seriously ill. Several doctors were called before one agreed to come to the remote island. The doctor and a nurse were brought by the Coast Guard and Iva Freeman's life was saved that night.

Mazie Anderson also described playing hide-and-go-seek on the island. Her favorite hiding place was on the ocean side of some rocks on a high cliff, where she learned to gain a toehold and inch her away across the face of the bluff. Mazie Anderson later married a Coast Guardsman and lived at Boston Light. She summed up her life at island light stations, saying she felt sad "for those who can never know such tranquility."

John Woodly was the Coast Guard keeper for a while in the early 1950s. He and his wife, Janice, had two young daughters, Jolene and Teresa. Teresa was once cut badly and her father had to carry her across the island to a dock where she was picked up by a boat to be taken for medical attention and stitches.

In February 1955, Coast Guard Seaman Richard Schwartz was stationed at Great Duck Island and his wife, Judy, was expecting a child. On February 6, about two weeks earlier than had been anticipated, Judy Schwartz went into labor. Because of rough seas, the tug that arrived to take the Schwartzes to the mainland could only dock at the north end of the island, opposite the lighthouse location. Dick and Judy Schwartz had to walk an hour and a half through deep snow to reach the vessel. Mrs. Schwartz was finally helped into the tug and taken to a hospital, where she gave birth to a baby boy. The Schwartzes had only been at Great Duck Island for two days and had just moved to Maine five days before this ordeal.

One of the last Coast Guardsman at Great Duck Island was Duncan Grant. He told Elinor De Wire, author of Guardians of the Lights, about the special talents of the station's two dogs. A golden retriever mix named Shannon became adept at digging up garter snakes and also developed the unusual ability to leap and hang by his mouth from a tree limb. The other dog, Boats, loved to climb trees and gaze at the distant mainland.

A newspaper article reported that Grant and the three other men stationed on Great Duck Island would play two-on-two baseball using a ball made out of old socks and duct tape. Video games and TV also helped pass the long hours.

Three keepers’ dwellings of six rooms each were built side by side near the lighthouse, along with; outbuildings and a brick fog signal building with a steam-operated horn were erected as well. A 1,200-pound bell was provided as backup. An oil house was added in 1901.

In 1902, the original lens was replaced by a fourth-order lens. Many other improvements to the station were made in the 1902-1906 period, including the addition of a tramway from the landing to the fog signal building.

Keeper William Stanley and his wife had three children. Their son, Lyford Stanley, who was two weeks old when the family arrived on the island, later worked as a lobster boat builder in Bass Harbor for more than 50 years. He told the Bangor Daily News about the difficult way of life on Great Duck Island. He recalled that supplies were delivered to the opposite side of the island and were carried by wheelbarrow to the keeper's house. He described one foggy period when the foghorn blew for 13 straight days. "It was noisy down there," he said.

The state provided no school for the island until 1902, when Nathan Adam "Ad" Reed arrived as an assistant keeper. Reed came to the island with his wife, Emma, and their 16 children. The Reeds were probably the largest family in American lighthouse history. One of the Reeds' older daughters, Rena, eventually got a teaching certificate in Castine and was able to teach her younger siblings in the tiny schoolroom.

An often-repeated story concerns a dog that survived a shipwreck and swam to Great Duck Island. The dog was adopted by a girl who lived with her parents at the north end of the island and named Seaboy. Two years later the dog's owner, a fisherman, unexpectedly appeared to claim his pet. As the man was about to leave with Seaboy in his dory, the dog heard the girl call to him. He ran back to the girl as the fisherman rowed away, never to return.

The story of Seaboy, told in great detail by Robert Thayer Sterling in his book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them, inspired a popular children's book, Captain's Castaway by Angeli Perrow and Emily Harris. Sterling was an assistant keeper at Great Duck Island for two years, and he professed a "particular fondness for this fine old station."

Andrew H. Kennedy was the principal keeper for several years in the 1930s. In September 1931, Kennedy and assistant keepers Earle Benson and Leverett Stanley went to the aid of the fishing schooner Rita A. Viator, which had grounded near the station during the night in heavy seas. The keepers rescued the captain and crew safely, and were honored for their efforts by special letters of commendation from Secretary of Commerce Robert P. Lamont.

James Freeman became keeper in 1940; he had previously been at Petit Manan Light. His daughter, Mazie Freeman Anderson, later wrote about a stormy night when her mother, Iva Freeman, became seriously ill. Several doctors were called before one agreed to come to the remote island. The doctor and a nurse were brought by the Coast Guard and Iva Freeman's life was saved that night.

Mazie Anderson also described playing hide-and-go-seek on the island. Her favorite hiding place was on the ocean side of some rocks on a high cliff, where she learned to gain a toehold and inch her away across the face of the bluff. Mazie Anderson later married a Coast Guardsman and lived at Boston Light. She summed up her life at island light stations, saying she felt sad "for those who can never know such tranquility."

John Woodly was the Coast Guard keeper for a while in the early 1950s. He and his wife, Janice, had two young daughters, Jolene and Teresa. Teresa was once cut badly and her father had to carry her across the island to a dock where she was picked up by a boat to be taken for medical attention and stitches.

In February 1955, Coast Guard Seaman Richard Schwartz was stationed at Great Duck Island and his wife, Judy, was expecting a child. On February 6, about two weeks earlier than had been anticipated, Judy Schwartz went into labor. Because of rough seas, the tug that arrived to take the Schwartzes to the mainland could only dock at the north end of the island, opposite the lighthouse location. Dick and Judy Schwartz had to walk an hour and a half through deep snow to reach the vessel. Mrs. Schwartz was finally helped into the tug and taken to a hospital, where she gave birth to a baby boy. The Schwartzes had only been at Great Duck Island for two days and had just moved to Maine five days before this ordeal.

One of the last Coast Guardsman at Great Duck Island was Duncan Grant. He told Elinor De Wire, author of Guardians of the Lights, about the special talents of the station's two dogs. A golden retriever mix named Shannon became adept at digging up garter snakes and also developed the unusual ability to leap and hang by his mouth from a tree limb. The other dog, Boats, loved to climb trees and gaze at the distant mainland.

A newspaper article reported that Grant and the three other men stationed on Great Duck Island would play two-on-two baseball using a ball made out of old socks and duct tape. Video games and TV also helped pass the long hours.

Another of the last Coast Guard keepers was Larry Baum (seen in the 1988 video clip above), who commented on life at Great Duck Island in a magazine article. "Cabin fever and boredom are problems with offshore lighthouse," he said, "especially when your four weeks are up and you aren't relieved because the weather prevents the boat or helicopter from coming. The mental strain can be bad. We had guys who jumped into a peapod and tried to row to the mainland."

The light was automated in 1986 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern optic. The Fresnel lens is reportedly in the possession of the Coast Guard in Boston.

In charge of the automation was Linwood Ginn, a 30-year veteran of the Coast Guard whose grandfather was a keeper at Mount Desert Rock Light. At the time Ginn said, "I hate to see them automated. I hate to see them closed up. They start deteriorating fast." The last Coast Guard officer in charge of the station was BM1 Donald Parker.

The light was automated in 1986 and the Fresnel lens was replaced by a modern optic. The Fresnel lens is reportedly in the possession of the Coast Guard in Boston.

In charge of the automation was Linwood Ginn, a 30-year veteran of the Coast Guard whose grandfather was a keeper at Mount Desert Rock Light. At the time Ginn said, "I hate to see them automated. I hate to see them closed up. They start deteriorating fast." The last Coast Guard officer in charge of the station was BM1 Donald Parker.

The light remains an active aid to navigation, while most of the rest of the island was purchased by the Maine Chapter of the Nature Conservancy in 1984. The Nature Conservancy estimates that Great Duck Island supports 20% of Maine's nesting seabirds.

The remaining keeper's house

In 1998 Great Duck Island Light, along with Mount Desert Rock Light, became the property of Bar Harbor's College of the Atlantic under the Maine Lights Program. The two lighthouses are used in the school's programs on ecology, botany and island life. The college must see that the properties' condition meets state historical preservation guidelines.

The College of the Atlantic's ongoing research projects on the island include the monitoring of the large nesting gull population, as well as detailed study of the rare Leach's storm petrel. This small bird nests in burrows on the island, many of which are very close to the lighthouse station. Students and staff from the college now live in the former keeper's dwelling much of the year.

Great Duck Island Light is difficult to see except by private boat or plane.

The College of the Atlantic's ongoing research projects on the island include the monitoring of the large nesting gull population, as well as detailed study of the rare Leach's storm petrel. This small bird nests in burrows on the island, many of which are very close to the lighthouse station. Students and staff from the college now live in the former keeper's dwelling much of the year.

Great Duck Island Light is difficult to see except by private boat or plane.

Use the player below to listen to an interview with John Anderson of College of the Atlantic on the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast "Light Hearted." (July 2020)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William F. Stanley (1890-1909); Joseph M. Gray, assistant (1901-1905), then principal keeper (1905-1920); Willis Dolliver, first assistant (1891-1894); John B. Thurston, second assistant (1891-1897); Edward Spurling, second assistant (1894-1898); Almon Mitchell, second assistant (1898-1899); Ephraim M. Johnson, second assistant (1899-1901); Elmer Reed, second assistant (c. 1901); Nathan A. Reed, assistant (1902-1912); Augustus "Gus" WIlson (assistant, c. 1910); Vinal Beal (1919-1921); Harvard Beal (second assistant, c. 1919-1921); Myrick Morrison (first assistant, c. 1919-1921); Edmund A. Howe (c. 1920-1928); Elmo J. Turner (c. 1920s); Leverett S. Stanley (assistant, 1924-1940); Andrew H. Kennedy (c. 1930-1935); Earle E. Benson (assistant, c. 1931); Harold E. Seavey (assistant, c. 1929-1933); W. L. Lockhart, assistant (c. 1935); Robert Thayer Sterling, assistant (c. 1930s); Eldon Cheney (c. 1939); James Freeman, (Coast Guard,1940-1943); Carroll Alley (Coast Guard c. 1949-1952); John Woodly (Coast Guard, c. early 1950s); Horace J. Smith (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Noel Gaiser (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Gary Shoberg (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Richard Schwartz (Coast Guard c. 1955); Todd Osier (Coast Guard BM2, officer in charge 1958-1959); Robert Lundberg (Coast Guard EN2 1958-1959); Dana Parker (Coast Guard, Jan. 1967- Jan. 1970); Larry Baum, (Coast Guard c. 1970s); Stanley B. (Red) Crossman Jr. (Coast Guard, 1973-1975); Phillip Dobbins (Coast Guard BM1, Officer in Charge c. mid-1970s); Rob Derrick (Coast Guard MK3, 1975-1976); Dennis Womack (Coast Guard MK1, c. mid-1970s); Ken Safford (Coast Guard, c. mid-1970s); Robert (Bob) Le Royer (Coast Guard Executive Petty Officer, February-November 1977); Duncan W. Grant (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Michael Notigan (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Bruce Reiner (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Rodney Metters (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Dan Inghram (Coast Guard, 1983); Max Small (Coast Guard BMC, c. 1981-1982); Mike Pell (Coast Guard, c. 1982); Sam Fuller (Coast Guard, 1980-1981); Dave Blum (Coast Guard, c. early 1980s); John Carter (Coast Guard, c. early 1980s); Larry Baum (Coast Guard BM1, c. 1982-1984); Donald Parker (Coast Guard BM1, Officer in Charge (?-12/1986); Richard Clark (Coast Guard MK3, ?-1986), Matthew Asselin (Coast Guard ET3, ?-12/1986)

William F. Stanley (1890-1909); Joseph M. Gray, assistant (1901-1905), then principal keeper (1905-1920); Willis Dolliver, first assistant (1891-1894); John B. Thurston, second assistant (1891-1897); Edward Spurling, second assistant (1894-1898); Almon Mitchell, second assistant (1898-1899); Ephraim M. Johnson, second assistant (1899-1901); Elmer Reed, second assistant (c. 1901); Nathan A. Reed, assistant (1902-1912); Augustus "Gus" WIlson (assistant, c. 1910); Vinal Beal (1919-1921); Harvard Beal (second assistant, c. 1919-1921); Myrick Morrison (first assistant, c. 1919-1921); Edmund A. Howe (c. 1920-1928); Elmo J. Turner (c. 1920s); Leverett S. Stanley (assistant, 1924-1940); Andrew H. Kennedy (c. 1930-1935); Earle E. Benson (assistant, c. 1931); Harold E. Seavey (assistant, c. 1929-1933); W. L. Lockhart, assistant (c. 1935); Robert Thayer Sterling, assistant (c. 1930s); Eldon Cheney (c. 1939); James Freeman, (Coast Guard,1940-1943); Carroll Alley (Coast Guard c. 1949-1952); John Woodly (Coast Guard, c. early 1950s); Horace J. Smith (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Noel Gaiser (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Gary Shoberg (Coast Guard, c. 1953); Richard Schwartz (Coast Guard c. 1955); Todd Osier (Coast Guard BM2, officer in charge 1958-1959); Robert Lundberg (Coast Guard EN2 1958-1959); Dana Parker (Coast Guard, Jan. 1967- Jan. 1970); Larry Baum, (Coast Guard c. 1970s); Stanley B. (Red) Crossman Jr. (Coast Guard, 1973-1975); Phillip Dobbins (Coast Guard BM1, Officer in Charge c. mid-1970s); Rob Derrick (Coast Guard MK3, 1975-1976); Dennis Womack (Coast Guard MK1, c. mid-1970s); Ken Safford (Coast Guard, c. mid-1970s); Robert (Bob) Le Royer (Coast Guard Executive Petty Officer, February-November 1977); Duncan W. Grant (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Michael Notigan (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Bruce Reiner (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Rodney Metters (Coast Guard c. 1980s); Dan Inghram (Coast Guard, 1983); Max Small (Coast Guard BMC, c. 1981-1982); Mike Pell (Coast Guard, c. 1982); Sam Fuller (Coast Guard, 1980-1981); Dave Blum (Coast Guard, c. early 1980s); John Carter (Coast Guard, c. early 1980s); Larry Baum (Coast Guard BM1, c. 1982-1984); Donald Parker (Coast Guard BM1, Officer in Charge (?-12/1986); Richard Clark (Coast Guard MK3, ?-1986), Matthew Asselin (Coast Guard ET3, ?-12/1986)