History of Dutch Island Lighthouse, Jamestown, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Dutch Island, between Jamestown to the east and Saunderstown (a village of North Kingstown) to the west, was known to the local Indians as Quetenis.

The 81-acre island got its present name because the West India Company established a trading post there in the 1630s. They traded Dutch goods in exchange for furs, meat and fish from the Indians.

The federal government acquired six acres at the southern tip of the island in 1825, and on January 1, 1827, a light station was established to mark the west passage of Narragansett Bay and to aid vessels entering Dutch Island Harbor. The first 30-foot tower was built of stones found on the island.

The federal government acquired six acres at the southern tip of the island in 1825, and on January 1, 1827, a light station was established to mark the west passage of Narragansett Bay and to aid vessels entering Dutch Island Harbor. The first 30-foot tower was built of stones found on the island.

The first keeper was Newport native William Dennis. Dennis had gone to sea at a young age and was in command of a merchant vessel based in London, but on receiving word of the outbreak of the American Revolution he returned home to fight for the colonists.

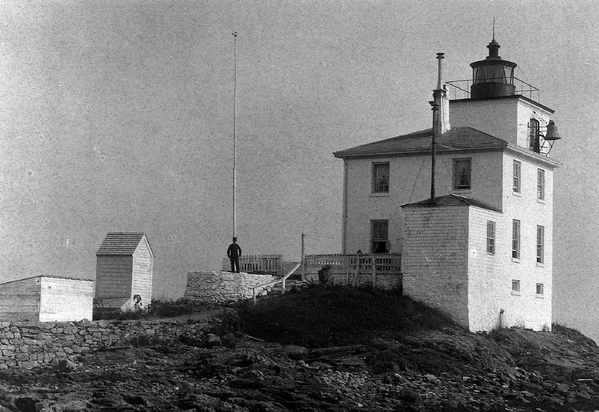

Circa 1859 (U.S. Coast Guard)

During the course of the war he commanded six different privateering vessels and was twice taken prisoner. He later served as sheriff of Newport County for a dozen years beginning in 1801.

Appointing war veterans as keepers was a common practice, but what made this case unusual was the fact that William Dennis was nearly 80 years old at the time he took the job in 1827.

He went on to become one of the oldest lighthouse keepers in New England history, serving to the age of 93. His son, Robert, later served as keeper.

The four-room keeper's dwelling and the lighthouse were described around the mid-nineteenth century as the "worst constructed of any in the state," and the lantern was described as "wretched." An 1850 inspection praised Keeper Robert Dennis, saying he was "a good honest man, and I think he shows a good light, although a moderate consumer of oil."

A second 42-foot brick tower and keeper's house were constructed for $4,000 in 1857, with a fourth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light.

George Fife became keeper in 1875. When a fog bell with striking machinery was added in 1878, with the bell protruding from a window near the top of the tower, Keeper Fife's wife was appointed as an assistant keeper to help with the extra duties. She retained the position until she and her husband left Dutch Island in 1883.

The early keepers had a well, but the brackish water was not suitable for drinking. A proper cistern for the collection of rainwater was added in the basement of the keeper's house in 1878.

Other than the lighthouse station and the pasturing of sheep, the island saw little activity in the nineteenth century until a Civil War encampment was established. Gun batteries were added after the Civil War, and the batteries were expanded around the turn of the century. By the late 1800s the fortifications were named Fort Greble, after Lieutenant John T. Greble, one of the first officers killed in the Civil War.

The facility housed as many as 495 personnel during World War I, but other nearby defense installations rendered Fort Greble expendable. The island's military use ended in 1947, but remnants of the buildings and gun emplacements remain.

Appointing war veterans as keepers was a common practice, but what made this case unusual was the fact that William Dennis was nearly 80 years old at the time he took the job in 1827.

He went on to become one of the oldest lighthouse keepers in New England history, serving to the age of 93. His son, Robert, later served as keeper.

The four-room keeper's dwelling and the lighthouse were described around the mid-nineteenth century as the "worst constructed of any in the state," and the lantern was described as "wretched." An 1850 inspection praised Keeper Robert Dennis, saying he was "a good honest man, and I think he shows a good light, although a moderate consumer of oil."

A second 42-foot brick tower and keeper's house were constructed for $4,000 in 1857, with a fourth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light.

George Fife became keeper in 1875. When a fog bell with striking machinery was added in 1878, with the bell protruding from a window near the top of the tower, Keeper Fife's wife was appointed as an assistant keeper to help with the extra duties. She retained the position until she and her husband left Dutch Island in 1883.

The early keepers had a well, but the brackish water was not suitable for drinking. A proper cistern for the collection of rainwater was added in the basement of the keeper's house in 1878.

Other than the lighthouse station and the pasturing of sheep, the island saw little activity in the nineteenth century until a Civil War encampment was established. Gun batteries were added after the Civil War, and the batteries were expanded around the turn of the century. By the late 1800s the fortifications were named Fort Greble, after Lieutenant John T. Greble, one of the first officers killed in the Civil War.

The facility housed as many as 495 personnel during World War I, but other nearby defense installations rendered Fort Greble expendable. The island's military use ended in 1947, but remnants of the buildings and gun emplacements remain.

Despite the presence of the light and fog bell, vessels frequently went aground on and near the island.

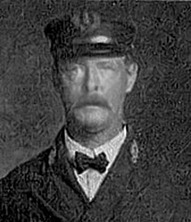

Keeper John Paul

On January 21, 1903, when Albert Henry Porter was keeper, the steamer Seaboard of the Joy Line "nearly knocked the little lighthouse . . . off the rocks," according to a newspaper account. The steamer had been making its way north in a thick fog, and was apparently going a bit too fast when the lighthouse suddenly appeared. Fortunately for the station and its residents, the jagged rocks at the southern end of the island halted the ship's progress about 30 feet from the tower. The steamer was badly damaged, but there were no casualties.

One of the more prominent wrecks at Dutch Island was the Rosalie, which ran up on the island in the early 1900s with a cargo consisting of barrels of white beans. It was reported that local boys found plenty of ammunition for their bean shooters that year.

The lighthouse almost met a premature demise in 1923. Someone was burning trash in the back yard of the keeper's house when the wind picked up and almost set the tower ablaze. Men stationed at the fort helped put out the fire, and only a storehouse was lost.

John Paul, previously at Fall River's Borden Flats Light, was keeper at Dutch Island from 1929 to 1931. Keeper Paul's son Louis later remembered that his father maintained a garden and kept ducks at the station. Keeper Paul found the fishing around the island first-rate; he would catch a "bushel of blackfish" before breakfast, according to his son. Keeper Paul would ride ashore occasionally on a ferry to pick up supplies in Saunderstown or Jamestown. He would buy huge quantities of food, sometimes a whole side of beef that he would salt for extended use at the light station.

One of the more prominent wrecks at Dutch Island was the Rosalie, which ran up on the island in the early 1900s with a cargo consisting of barrels of white beans. It was reported that local boys found plenty of ammunition for their bean shooters that year.

The lighthouse almost met a premature demise in 1923. Someone was burning trash in the back yard of the keeper's house when the wind picked up and almost set the tower ablaze. Men stationed at the fort helped put out the fire, and only a storehouse was lost.

John Paul, previously at Fall River's Borden Flats Light, was keeper at Dutch Island from 1929 to 1931. Keeper Paul's son Louis later remembered that his father maintained a garden and kept ducks at the station. Keeper Paul found the fishing around the island first-rate; he would catch a "bushel of blackfish" before breakfast, according to his son. Keeper Paul would ride ashore occasionally on a ferry to pick up supplies in Saunderstown or Jamestown. He would buy huge quantities of food, sometimes a whole side of beef that he would salt for extended use at the light station.

Ernest Homer Stacey, originally from Rouses Point, New York, arrived as keeper in 1941. Although Stacey loved living at Dutch Island, his wife, Dot, was a "city girl" and wasn't so pleased.

Dutch Island held countless annoyances for Dot Stacey. Before she'd use the water from the cistern in the basement for washing their laundry, she insisted on boiling it because she claimed it had an odd smell. Dot once hung the laundry outside to dry, only to have a sudden strong wind blow it into the bay. She wasn't at all amused when Keeper Stacey fished out her bloomers three days later.

Left: Ernest Stacey was the last keeper. Courtesy of his daughter, Angel (Crissie Stacey) Derouchie.

The light's characteristic was changed to occulting red in 1924. The light was automated in 1947, and the last keeper, Ernest Stacey, was removed.

In 1958, after the military use of the island had ended, the entire island except for the light station was deeded to the state of Rhode Island. The deed stated that the island was to be used "for the conservation of wildlife."

A report in April of 1960 stated that the keeper's house had "deteriorated greatly in the past 10 years; that all windows and doors have been broken or removed; all paint is peeling; several areas of plaster have fallen, and the roof whos signs of leaking." The report also indicated that the wooden boathouse had been moved about 100 feet in a recent storm. The dwelling and boathouse were demolished by the Coast Guard a short time later.

Left: Ernest Stacey was the last keeper. Courtesy of his daughter, Angel (Crissie Stacey) Derouchie.

The light's characteristic was changed to occulting red in 1924. The light was automated in 1947, and the last keeper, Ernest Stacey, was removed.

In 1958, after the military use of the island had ended, the entire island except for the light station was deeded to the state of Rhode Island. The deed stated that the island was to be used "for the conservation of wildlife."

A report in April of 1960 stated that the keeper's house had "deteriorated greatly in the past 10 years; that all windows and doors have been broken or removed; all paint is peeling; several areas of plaster have fallen, and the roof whos signs of leaking." The report also indicated that the wooden boathouse had been moved about 100 feet in a recent storm. The dwelling and boathouse were demolished by the Coast Guard a short time later.

All that remains today is the lighthouse, a 1938 concrete engine house, and the remains of a well.

In 1962, the light station property, except for the tower, was transferred to the state of Rhode Island. The island and lighthouse are now owned by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM). The Coast Guard proposed discontinuing the light in 1972, saying it had outlived its usefulness. They pointed out that in January of that year the light had been out for several days before anyone reported the problem to authorities. There was tremendous opposition to discontinuing the light.

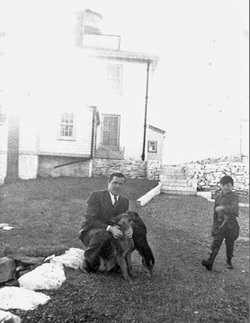

Right: Ernest Stacey and son Robert at the lighthouse. Courtesy of Angel (Crissie Stacey) Derouchie.

Several petitions and 40 to 50 letters opposing the move were received by the Aids to Navigation office in Boston, and the Rhode Island Natural Resources Department said the light was needed to guide small craft to Dutch Island Harbor. As a result of this pressure, the Coast Guard not only retained the light, but actually increased its intensity.

Due to rampant vandalism, the Coast Guard again proposed discontinuing the light in 1977. In that year alone, vandals smashed the door and stole equipment. Someone even poured liquid steel into a lock. It was just too expensive for the Coast Guard to keep up with the repairs, and Dutch Island Light was officially discontinued in 1979, replaced by offshore buoys.

Right: Ernest Stacey and son Robert at the lighthouse. Courtesy of Angel (Crissie Stacey) Derouchie.

Several petitions and 40 to 50 letters opposing the move were received by the Aids to Navigation office in Boston, and the Rhode Island Natural Resources Department said the light was needed to guide small craft to Dutch Island Harbor. As a result of this pressure, the Coast Guard not only retained the light, but actually increased its intensity.

Due to rampant vandalism, the Coast Guard again proposed discontinuing the light in 1977. In that year alone, vandals smashed the door and stole equipment. Someone even poured liquid steel into a lock. It was just too expensive for the Coast Guard to keep up with the repairs, and Dutch Island Light was officially discontinued in 1979, replaced by offshore buoys.

Shirley Sheldon of Saunderstown and other nearby residents initiated a preservation effort. The effort was abandoned when the group realized the deterioration of the lighthouse was worse than they had feared.

The lighthouse in 2000

Then, a group from the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF) visited the lighthouse in May 2000, accompanied by Chris Powell of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Division of Fish and Wildlife. The Dutch Island Lighthouse Society (DILS) was subsequently founded to work for the restoration of the lighthouse. The lighthouse was found to be in poor condition but restorable. DILS was later recommended for $120,000 in Transportation Enhancement funding under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21).

After a formal bid process, Abcore Restoration Co., Inc., was awarded the contract for the restoration. Abcore previously restored the Plum Beach and Pomham Rocks lighthouses in Rhode Island. The federal/state grant covered most of the base cost of restoration ($160,000).

The work was completed in November 2007. At a little after 7:00 p.m. on November 17, the lighthouse was relighted as an aid to navigation. Restoration has included interior and exterior repairs to the brick lighthouse tower, guano removal, replacement of floors and metalwork, and the repair of interior stairs. Graffiti and rust have been covered over, and the tower now has a white stucco finish.

The lighthouse can be viewed from the Fort Getty Recreation Area. There is a fee to enter the area, but if you explain that you just want to photograph the lighthouse you might be allowed in for a short visit.

After a formal bid process, Abcore Restoration Co., Inc., was awarded the contract for the restoration. Abcore previously restored the Plum Beach and Pomham Rocks lighthouses in Rhode Island. The federal/state grant covered most of the base cost of restoration ($160,000).

The work was completed in November 2007. At a little after 7:00 p.m. on November 17, the lighthouse was relighted as an aid to navigation. Restoration has included interior and exterior repairs to the brick lighthouse tower, guano removal, replacement of floors and metalwork, and the repair of interior stairs. Graffiti and rust have been covered over, and the tower now has a white stucco finish.

The lighthouse can be viewed from the Fort Getty Recreation Area. There is a fee to enter the area, but if you explain that you just want to photograph the lighthouse you might be allowed in for a short visit.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

William Dennis (1827-1843), Robert H. Weeden (1843-1844), William P. Babcock (1844-1846), Robert Dennis (1846-1853), Benjamin Congdon (1853-1859), M. M. Trundy (1859-1865), W. W. Wales (1865-1873 ), Andrew King (1873-1875), George Fife (1875-1883), Mrs. M. Fife (assistant 1878-1883), H. W. Crawford (1883-1885), Lewis T. King (1885 -1901), Albert Henry Porter (1901-1916), John J. Cook (1916-1929), John Paul (1929-1931), John D. Davies (1931-1934?), Stanley Gunderson (c.1934-1935); William C. Anderson (1935-1937), Ernest H. Stacey (Coast Guard BM2, May 22, 1941-May 21, 1947)

William Dennis (1827-1843), Robert H. Weeden (1843-1844), William P. Babcock (1844-1846), Robert Dennis (1846-1853), Benjamin Congdon (1853-1859), M. M. Trundy (1859-1865), W. W. Wales (1865-1873 ), Andrew King (1873-1875), George Fife (1875-1883), Mrs. M. Fife (assistant 1878-1883), H. W. Crawford (1883-1885), Lewis T. King (1885 -1901), Albert Henry Porter (1901-1916), John J. Cook (1916-1929), John Paul (1929-1931), John D. Davies (1931-1934?), Stanley Gunderson (c.1934-1935); William C. Anderson (1935-1937), Ernest H. Stacey (Coast Guard BM2, May 22, 1941-May 21, 1947)