History of Egg Rock Light, Nahant, Massachusetts

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Egg Rock, a little less than a mile northeast of the town of Nahant, resembles a whitish-gray whale rising out of the ocean. The three-acre island -- about 80 feet high -- can be seen from many locations north of Boston, from Winthrop to Marblehead.

The island is often battered by fierce wind and waves, and is frequently icebound in winter.

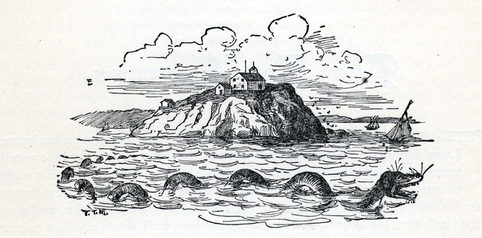

The area around Egg Rock is one of many locations on Boston's North Shore where reported sea serpent sightings were common for centuries. There were many reported sightings in 1819, again in the early 1830s, and at least as late as 1875.

According to a newspaper report, one day in August 1832 more than 150 people watched from Nahant as a large serpent cavorted between Egg Rock and the mainland.

The area around Egg Rock is one of many locations on Boston's North Shore where reported sea serpent sightings were common for centuries. There were many reported sightings in 1819, again in the early 1830s, and at least as late as 1875.

According to a newspaper report, one day in August 1832 more than 150 people watched from Nahant as a large serpent cavorted between Egg Rock and the mainland.

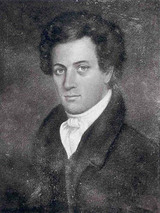

Alonzo Lewis (1794-1861), a historian, poet, and civil engineer from Lynn (adjacent to Nahant), described the island:

Viewed from the north it has the semblance of a couchant lion, lying out in front of the town, to protect it from the approach of a foreign enemy.

Alonzo Lewis

Nahant's neighbor Swampscott had a fleet of about 150 fishing vessels in the mid-1800s. Alonzo Lewis was one of those who petitioned for a lighthouse on Egg Rock, particularly after an 1843 schooner wreck in the vicinity claimed five lives.

Congress appropriated $5,000 in 1850, but the project was delayed and the funds had to be re-appropriated in 1854.

The first lighthouse on the island was built by contractor Ira P. Brown on the island at a cost of $3,700 in 1856. A lantern was located on top of the small stone dwelling, which had no cellar. The stone for the building appears to have been cut from the island itself.

Congress appropriated $5,000 in 1850, but the project was delayed and the funds had to be re-appropriated in 1854.

The first lighthouse on the island was built by contractor Ira P. Brown on the island at a cost of $3,700 in 1856. A lantern was located on top of the small stone dwelling, which had no cellar. The stone for the building appears to have been cut from the island itself.

The lighthouse's fifth-order Fresnel lens produced a fixed white light, first exhibited on September 15, 1856.

It was changed to red a year later in reaction to the wreck of the schooner Shark, whose captain had mistaken Egg Rock Light for Long Island Head Light in Boston Harbor.

The first keeper was George B. Taylor of Nahant, who lived at the lighthouse with his wife, Mary, and their children, along with chickens, goats, a tame crow, and a dog named Milo.

A newspaper article reported that Taylor had a garden and grew beets that were "hard to beat by any gardener on the more favored shore."

The first keeper was George B. Taylor of Nahant, who lived at the lighthouse with his wife, Mary, and their children, along with chickens, goats, a tame crow, and a dog named Milo.

A newspaper article reported that Taylor had a garden and grew beets that were "hard to beat by any gardener on the more favored shore."

One of the most famous of all lighthouse pets was Milo, the Taylors' huge Newfoundland-St. Bernard mix.

"Saved!" by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer

One day, Keeper Taylor was shooting waterfowl on the island, with Milo accompanying him. The keeper shot a loon, which fell to the ocean. The bird was wounded, but not mortally. Milo swam in pursuit, but the loon took off and flew a short distance. Every time Milo would close in, the bird would take off again.

Taylor watched the chase from shore until Milo and the loon disappeared from sight. Milo wasn't seen again that day. The next day, Milo was seen swimming from Nahant, where he apparently spent the night. He swam safely back to his home at the Rock.

Local fishermen enjoyed playing a game with Milo. They would lash two or three cod to pieces of wood and Milo would retrieve the bundles, sometimes as far as a mile from the island, and bring them to the Taylors for dinner. In foggy weather, Milo also served as a kind of fog signal, barking at vessels as they approached Egg Rock. Keeper Taylor said that his dog was as useful as the light.

Taylor watched the chase from shore until Milo and the loon disappeared from sight. Milo wasn't seen again that day. The next day, Milo was seen swimming from Nahant, where he apparently spent the night. He swam safely back to his home at the Rock.

Local fishermen enjoyed playing a game with Milo. They would lash two or three cod to pieces of wood and Milo would retrieve the bundles, sometimes as far as a mile from the island, and bring them to the Taylors for dinner. In foggy weather, Milo also served as a kind of fog signal, barking at vessels as they approached Egg Rock. Keeper Taylor said that his dog was as useful as the light.

Over the next few years, Milo achieved fame as the rescuer of several children around Egg Rock.

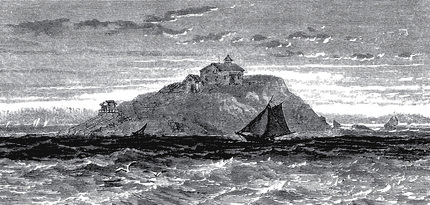

Egg Rock Light circa 1890

An artist, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, painted a portrait of Milo with Keeper Taylor's young son, Frank, nestled between the dog's paws. This painting, captioned "Saved," became famous across America. [Note: Some sources say that Keeper Taylor's son Fred posed for the painting. Research shows that Taylor had a son named Frank, but no son named Fred.]

An 1860 article described life at Egg Rock:

We found Mrs.Taylor quite contented and happy with her lot, and she assured us that she as well as the children had become attached to the place, and were homesick if compelled to remain upon the shore for any great length of time. During the summer months large numbers visit the rock, as many as three hundred having been there during the month of August... It made us a little nervous to see the children running about and skipping from rock to rock, but the parents informed us that they were quite used to it and have never yet met with an accident, except when one of them fell from the doorstep.

Keeper Taylor lost his job for political reasons in 1860. Thomas Widger, the second keeper, was at Egg Rock from 1861 to 1871. Widger and his wife had three sons born on the island during their years there, as well as two daughters born ashore in Swampscott.

An 1860 article described life at Egg Rock:

We found Mrs.Taylor quite contented and happy with her lot, and she assured us that she as well as the children had become attached to the place, and were homesick if compelled to remain upon the shore for any great length of time. During the summer months large numbers visit the rock, as many as three hundred having been there during the month of August... It made us a little nervous to see the children running about and skipping from rock to rock, but the parents informed us that they were quite used to it and have never yet met with an accident, except when one of them fell from the doorstep.

Keeper Taylor lost his job for political reasons in 1860. Thomas Widger, the second keeper, was at Egg Rock from 1861 to 1871. Widger and his wife had three sons born on the island during their years there, as well as two daughters born ashore in Swampscott.

When the birth of one of their sons was imminent, Keeper Widger rowed his dory to shore and enlisted the help of a Swampscott midwife. In heavy surf the dory capsized and threw the pair overboard. The woman refused to go any further. Keeper Widger had to row alone back to Egg Rock, and his son, Abraham, was born a short time later.

There wasn't much soil on Egg Rock, but Abraham Widger later remembered that his family had a vegetable garden. They also kept chickens and pigs. "We never gave the neighbors any trouble," said Widger. "They were too far away on shore."

An entry in the station's log in 1873, when Henry N. Richardson was keeper, read:

A severe rainstorm. Keeper went ashore to get some groceries and got caught in the storm; was detained away four days on account of the rough seas. The wife kept the light all trimmed and burning bright and clear. Keeper was drunk ashore all the time.

The keeper's daughter, who was twelve years old in 1873, later claimed that she was the one who kept the light going during her father's absence.

Another of Richardson's entries:

May 1873 - Eben Phillips caught a cod off the rock & gold ring in it, 18k with H.L. marked on it.

(Note: Poor Mr. Phillips had already sold the cod when the ring was discovered inside)

There's a story involving a keeper of Egg Rock Light that has been passed down through the years, but which appears to be legend rather than fact. It seems the wife of one of the keepers in the latter part of the nineteenth century died in the early winter. Egg Rock was surrounded by ice, so the keeper couldn't bring the body to the mainland. Instead he laid her in an outbuilding, where she soon froze solid.

In the early spring, when the ice had cleared enough, the keeper rowed his wife's body to the mainland. A funeral was held that day. After the funeral the keeper visited with an old childhood sweetheart. He hastily proposed marriage, and the same preacher who had performed the keeper's first wife's funeral just hours earlier married the couple. The keeper was back at Egg Rock with his new wife before nightfall, according to the legend.

An entry in the station's log in 1873, when Henry N. Richardson was keeper, read:

A severe rainstorm. Keeper went ashore to get some groceries and got caught in the storm; was detained away four days on account of the rough seas. The wife kept the light all trimmed and burning bright and clear. Keeper was drunk ashore all the time.

The keeper's daughter, who was twelve years old in 1873, later claimed that she was the one who kept the light going during her father's absence.

Another of Richardson's entries:

May 1873 - Eben Phillips caught a cod off the rock & gold ring in it, 18k with H.L. marked on it.

(Note: Poor Mr. Phillips had already sold the cod when the ring was discovered inside)

There's a story involving a keeper of Egg Rock Light that has been passed down through the years, but which appears to be legend rather than fact. It seems the wife of one of the keepers in the latter part of the nineteenth century died in the early winter. Egg Rock was surrounded by ice, so the keeper couldn't bring the body to the mainland. Instead he laid her in an outbuilding, where she soon froze solid.

In the early spring, when the ice had cleared enough, the keeper rowed his wife's body to the mainland. A funeral was held that day. After the funeral the keeper visited with an old childhood sweetheart. He hastily proposed marriage, and the same preacher who had performed the keeper's first wife's funeral just hours earlier married the couple. The keeper was back at Egg Rock with his new wife before nightfall, according to the legend.

Charles M. Dunham became keeper in 1884 after time at Thacher Island, off Rockport.

Here are two of Dunham's log entries:

August 18, 1884: Went to Nahant with wife, her first shore visit since September 28, 1883.

December 23-24: Could not get ashore, and consequently no Christmas presents.

On May 28, 1885, the keeper and his wife Mary (Mills) had a daughter born at the lighthouse, Ada Isidore Dunham. Their older daughter, Dora, said years later:

I have many times been on the street in Nahant and Lynn and would hear, when passing, "There goes the Egg Rock girl," and heads would be turned, as if I were a natural curiosity, not expected to know anything or have any feelings.

On September 18, 1885, Keeper Dunham rescued a New Hampshire man whose canoe had overturned neat Egg Rock. Dunham later received a Humane Society Life Saving medal for the July 1889 rescue of two men whose small sloop had capsized in a squall.

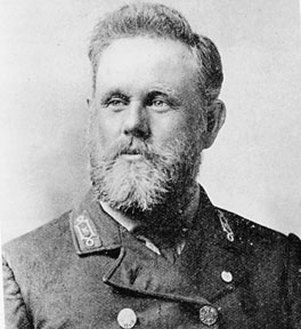

Right: Keeper George L. Lyon. Courtesy of Tim Harrison, originally from Lightkeeper magazine.

August 18, 1884: Went to Nahant with wife, her first shore visit since September 28, 1883.

December 23-24: Could not get ashore, and consequently no Christmas presents.

On May 28, 1885, the keeper and his wife Mary (Mills) had a daughter born at the lighthouse, Ada Isidore Dunham. Their older daughter, Dora, said years later:

I have many times been on the street in Nahant and Lynn and would hear, when passing, "There goes the Egg Rock girl," and heads would be turned, as if I were a natural curiosity, not expected to know anything or have any feelings.

On September 18, 1885, Keeper Dunham rescued a New Hampshire man whose canoe had overturned neat Egg Rock. Dunham later received a Humane Society Life Saving medal for the July 1889 rescue of two men whose small sloop had capsized in a squall.

Right: Keeper George L. Lyon. Courtesy of Tim Harrison, originally from Lightkeeper magazine.

George L. Lyon of Lynn became keeper in 1889. Charles A. Lawrence visited Egg Rock (along with newspaper reporter Walter Ramsdell, a future mayor of Lynn) and later described Keeper Lyon, who was previously an assistant keeper at Minot's Light:

Bronzed and blue-shirted, his yellow beard suggested the Norseman of old... His cordial welcome was seconded by his mother, a woman then almost ninety years of age...

During a tour of the lighthouse, the keeper told Lawrence:

Lots of people ask us what makes the light red, and we tell 'em it's the red oil. Some of 'em don't get it, and they say, 'Oh, that's it. I never knew.'

During more than two decades at Egg Rock, Keeper Lyon took a correspondence course in mechanical drawing. He was a carpenter, boat builder, reportedly an expert marksman with a rifle, and his mechanical aptitude enabled him to repair the dory engines of many local fishermen. He also built and raced his own dories.

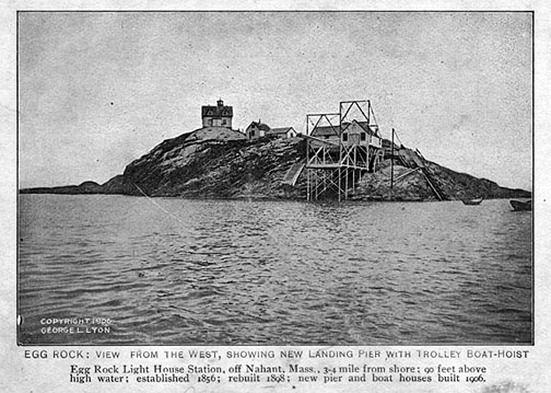

Lyon's crowning achievement at Egg Rock was the invention of a landing stage (left) on the island. With this arrangement a boat landing on the island was actually hoisted out of the water onto a deck, then hoisted into a boathouse. A powerful hand winch was used for both hoists.

Lots of people ask us what makes the light red, and we tell 'em it's the red oil. Some of 'em don't get it, and they say, 'Oh, that's it. I never knew.'

During more than two decades at Egg Rock, Keeper Lyon took a correspondence course in mechanical drawing. He was a carpenter, boat builder, reportedly an expert marksman with a rifle, and his mechanical aptitude enabled him to repair the dory engines of many local fishermen. He also built and raced his own dories.

Lyon's crowning achievement at Egg Rock was the invention of a landing stage (left) on the island. With this arrangement a boat landing on the island was actually hoisted out of the water onto a deck, then hoisted into a boathouse. A powerful hand winch was used for both hoists.

George Lyon was responsible for many rescues in the vicinity of Egg Rock. Once, after the keeper saved a group of five men, they took up a collection and presented a not-so-generous reward of 85 cents to their rescuer.

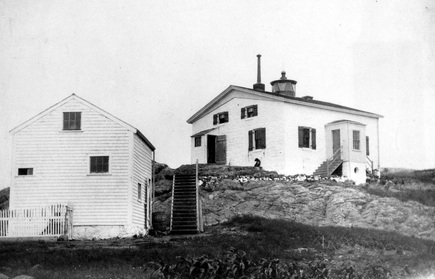

Egg Rock Light circa 1905

Lyon had a Newfoundland dog at the lighthouse with the strange name of "O-who." O-who loved to fetch sticks thrown by the keeper into the waves, and he rode along and "assisted" in some of the rescues around the island. Charles Lawrence called O-who a "sailor at heart." The dog was succeeded at Egg Rock by a family of black cocker spaniels.

Keeper Lyon was aided on the island by a local young woman named Ada Foster. The two later planned to be married, but Ada died before the marriage could take place, when Lyon was keeper at Nobska Point Light.

The lighthouse was rebuilt in 1897, but not before the workmen's shanty was destroyed by fire. The contractor for the new building was John McDuffie. A 19-year-old local resident named Joe White was in charge of bringing materials out to the island in a dory, and it was said that over the course of the project he made the round trip over 300 times.

Keeper Lyon was aided on the island by a local young woman named Ada Foster. The two later planned to be married, but Ada died before the marriage could take place, when Lyon was keeper at Nobska Point Light.

The lighthouse was rebuilt in 1897, but not before the workmen's shanty was destroyed by fire. The contractor for the new building was John McDuffie. A 19-year-old local resident named Joe White was in charge of bringing materials out to the island in a dory, and it was said that over the course of the project he made the round trip over 300 times.

The new lighthouse consisted of a square brick tower connected to a six-room wood-frame dwelling. An oil house was built in 1904, and a new pier and boat house were added in 1906.

During World War I, the light at Egg Rock was dimmed out of fear of enemy submarines in the area. Around this time a telephone cable connected the lighthouse to the mainland. The Lighthouse Service stationed a succession of young men on the island to look after the light.

It became a popular pastime for some of the young women in the area to call the lighthouse and chat with the young men to help them pass the lonely hours. The life of one of those men might have been saved by the phone calls, as the young women convinced him to stay at the lighthouse during a bad storm instead of making a risky trip to shore.

In 1919, an automatic gas-operated beacon was placed in the tower. The Lynn Daily Evening Item of January 31, 1919 reported:

It gives one a queer, unromantic sort of feeling to look out upon the sightly landmark of Egg Rock on a winter's evening and see the clear white gas beacon which now shines from the famous rock, untouched by the hand of man. For the long-to-be-pitied, forlorn, lonesome light keeper of Egg Rock is no more. Modern invention has supplanted this heroic figure of the north shore by an automation, in the shape of a huge tank, which quite uncannily, feeds the great beacon light of Lynn, Nahant and Swampscott shores.

Then, in 1922, the light was discontinued. The government sold the buildings at auction for $160. The catch was that the buyer had to remove the buildings from the island at his own expense. The buyer, John Cavanaugh of Milton, Massachusetts, planned to move the lighthouse to Quincy, south of Boston. A crew was hired to move the structure onto a barge.

In preparation, the dwelling was separated from the tower. The house was jacked up and placed on rollers, and was moved about 50 feet successfully before disaster struck.

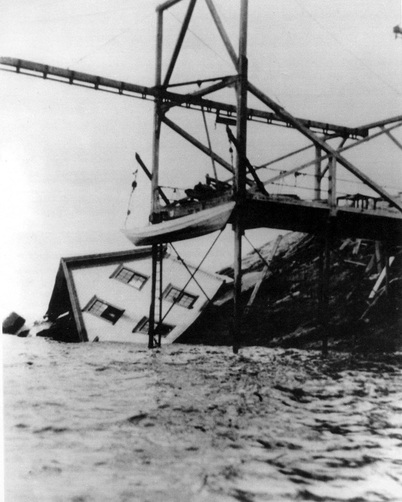

Left: The demise of the Egg Rock keeper's house. Courtesy of the Lynn Historical Society.

It became a popular pastime for some of the young women in the area to call the lighthouse and chat with the young men to help them pass the lonely hours. The life of one of those men might have been saved by the phone calls, as the young women convinced him to stay at the lighthouse during a bad storm instead of making a risky trip to shore.

In 1919, an automatic gas-operated beacon was placed in the tower. The Lynn Daily Evening Item of January 31, 1919 reported:

It gives one a queer, unromantic sort of feeling to look out upon the sightly landmark of Egg Rock on a winter's evening and see the clear white gas beacon which now shines from the famous rock, untouched by the hand of man. For the long-to-be-pitied, forlorn, lonesome light keeper of Egg Rock is no more. Modern invention has supplanted this heroic figure of the north shore by an automation, in the shape of a huge tank, which quite uncannily, feeds the great beacon light of Lynn, Nahant and Swampscott shores.

Then, in 1922, the light was discontinued. The government sold the buildings at auction for $160. The catch was that the buyer had to remove the buildings from the island at his own expense. The buyer, John Cavanaugh of Milton, Massachusetts, planned to move the lighthouse to Quincy, south of Boston. A crew was hired to move the structure onto a barge.

In preparation, the dwelling was separated from the tower. The house was jacked up and placed on rollers, and was moved about 50 feet successfully before disaster struck.

Left: The demise of the Egg Rock keeper's house. Courtesy of the Lynn Historical Society.

In October 1922, as the crew slowly moved the building, a cable snapped. The house slid down the rocks and hung precariously at the edge of the ocean. There were several workmen inside the dwelling when this occurred, but they managed to break windows and escape to safety.

There was still some hope that the building could be salvaged and moved to shore in pieces, but it collapsed into the sea a few days later. For some time the remains of the dwelling washed up on local beaches.

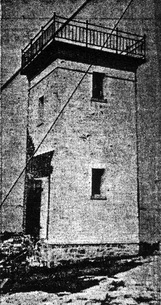

The brick lighthouse tower (right) stood until 1927, when it was destroyed. At that time all the remaining wooden structures on the island were burned. The state of Massachusetts took over Egg Rock in 1927 and maintained it as a bird sanctuary.

Egg Rock Light survives only in history and legend.

The brick lighthouse tower (right) stood until 1927, when it was destroyed. At that time all the remaining wooden structures on the island were burned. The state of Massachusetts took over Egg Rock in 1927 and maintained it as a bird sanctuary.

Egg Rock Light survives only in history and legend.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

George B. Taylor (1856-1861); Thomas Widger (1861-1871); Henry N. Richardson (1871-1874); Charles Hooper (1874-1883); George Wadleigh (1883-1884); Charles Dunham (1884-1889); George L. Lyon (1889-1911); Malcom (Malcolm?) N. Huse (1911-?); Andrew S. Nickerson (?); James Yates (?)

George B. Taylor (1856-1861); Thomas Widger (1861-1871); Henry N. Richardson (1871-1874); Charles Hooper (1874-1883); George Wadleigh (1883-1884); Charles Dunham (1884-1889); George L. Lyon (1889-1911); Malcom (Malcolm?) N. Huse (1911-?); Andrew S. Nickerson (?); James Yates (?)