History of Portland Head Light, Cape Elizabeth, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

The rocky ledge runs far out into the sea / And on its outer point, some miles away, / The lighthouse lifts its massive masonry, / A pillar of fire by night, of cloud by day. -- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, "The Lighthouse"

The U.S.S. Constitution passes Portland Head Light on July 23, 1931

Edward Rowe Snow, the popular historian and raconteur of the New England coast, wrote in his book Famous New England Lighthouses, “Portland Head and its light seem to symbolize the state of Maine—rocky coast, breaking waves, sparkling water and clear, pure salt air.”

The hundreds of thousands of people who visit Portland Head each year would agree; this is one of the most strikingly beautiful lighthouse locations in New England.

The city of Portland took its name from the headland where the lighthouse now stands, but Portland Head is now within the boundaries of the town of Cape Elizabeth.

Portland, which was known as Falmouth until 1786, was America’s sixth busiest port by the 1790s. There were no lighthouses on the coast of Maine when 74 merchants petitioned the Massachusetts government (Maine was part of Massachusetts at the time) in 1784 for a light at Portland Head, on the northeast coast of Cape Elizabeth, to mark the entrance to Portland Harbor. The deaths of two people in a 1787 shipwreck at Bangs (now Cushing) Island, near Portland Head, led to the appropriation of 150 pounds (roughly $700) for a lighthouse in June 1789. Construction began in August 1789.

The hundreds of thousands of people who visit Portland Head each year would agree; this is one of the most strikingly beautiful lighthouse locations in New England.

The city of Portland took its name from the headland where the lighthouse now stands, but Portland Head is now within the boundaries of the town of Cape Elizabeth.

Portland, which was known as Falmouth until 1786, was America’s sixth busiest port by the 1790s. There were no lighthouses on the coast of Maine when 74 merchants petitioned the Massachusetts government (Maine was part of Massachusetts at the time) in 1784 for a light at Portland Head, on the northeast coast of Cape Elizabeth, to mark the entrance to Portland Harbor. The deaths of two people in a 1787 shipwreck at Bangs (now Cushing) Island, near Portland Head, led to the appropriation of 150 pounds (roughly $700) for a lighthouse in June 1789. Construction began in August 1789.

The project was delayed by insufficient funds, and construction didn't progress until 1790 when Congress appropriated an additional $1,500, after the nation's lighthouses had been ceded to the federal government.

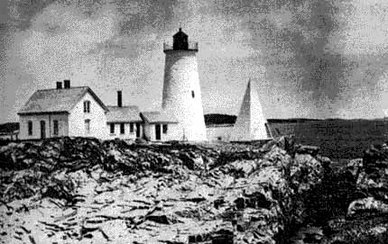

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

The stone lighthouse was built by local masons Jonathan Bryant and John Nichols. The original plan was for a 58-foot tower, but when it was realized that the light would be blocked from the south it was decided to make the tower 72 feet in height instead. Bryant resigned over the change, and Nichols finished the lighthouse in January 1791.

President George Washington approved the appointment of Capt. Joseph Greenleaf, a veteran of the American Revolution, as first keeper. The light went into service on January 10, 1791, with whale oil lamps showing a fixed white light. At first, Greenleaf received no salary as keeper; his payment was the right to fish and farm and to live in the keeper’s house. As early as November 1791, Greenleaf wrote that he couldn’t afford to remain keeper without financial compensation. In a June 1792 letter, he complained of many hardships. During the previous winter, he wrote, the ice on the lantern glass was often so thick that he had to melt it off. In 1793, Greenleaf was granted an annual salary of $160.

Greenleaf died of an apparent stroke while in his boat on the Fore River in October 1795. According to the Eastern Argus, he had “faithfully discharged his duty to the satisfaction of those who occupy their business on great waters.”

After a short stay by Reuben Freeman, Barzillai Delano, a blacksmith who had lobbied for the appointment when the lighthouse was first built, became keeper in 1796. Delano’s salary of $225 yearly was raised to $300 in 1812, after a petition with 22 signatures was submitted on his behalf.

By 1810, the woodwork in the lighthouse and keeper’s house were in poor condition; the woodwork was damp and rotting. Part of the problem was that the keeper was storing a year’s supply of oil in one room, which putting great stress on the floor. Repairs were made, and an oil shed was added.

The tower continued to have problems with leaks. In November 1812, the contractor Winslow Lewis offered the opinion that the upper 20 feet of the tower was very poorly built. The lantern, which was only 5 feet in diameter, was also badly constructed. Lewis recommended reducing the tower’s height by 20 feet in height, along with the addition of a new lantern. Lewis carried out these changes in 1813, along with the installation of a system of lamps and reflectors designed by Lewis himself, at a cost of $2,100. About 25 feet of stonework at the top of the tower was removed.

The contractor Henry Dyer of Cape Elizabeth built a new keeper’s house in 1816 for $1,175. The one-story stone cottage was 20 by 34 feet, with and comprised two rooms, an attached kitchen, and an attic. The kitchen ell was attached to outbuildings, which, in turn, were joined to the tower. The joining of the house to the tower had been requested in 1809 by Delano, the keeper, who complained that the space between the buildings was often frozen over in winter and that the sea sometimes washed over the area.

Barzillai Delano died in 1820; his son, James Delano, later served as keeper from 1854 to 1861. Joshua Freeman, who would become known for his jovial hospitality, became keeper in 1820. Freeman kept a supply of rum and other spirits in a cupboard, and he’d sell it drinks for three cents a glass to visitors who came to fish. The top-shelf liquor was reserved for the local minister.

An 1825 article in the Eastern Argus described the pleasures of a visit to Portland Head:

President George Washington approved the appointment of Capt. Joseph Greenleaf, a veteran of the American Revolution, as first keeper. The light went into service on January 10, 1791, with whale oil lamps showing a fixed white light. At first, Greenleaf received no salary as keeper; his payment was the right to fish and farm and to live in the keeper’s house. As early as November 1791, Greenleaf wrote that he couldn’t afford to remain keeper without financial compensation. In a June 1792 letter, he complained of many hardships. During the previous winter, he wrote, the ice on the lantern glass was often so thick that he had to melt it off. In 1793, Greenleaf was granted an annual salary of $160.

Greenleaf died of an apparent stroke while in his boat on the Fore River in October 1795. According to the Eastern Argus, he had “faithfully discharged his duty to the satisfaction of those who occupy their business on great waters.”

After a short stay by Reuben Freeman, Barzillai Delano, a blacksmith who had lobbied for the appointment when the lighthouse was first built, became keeper in 1796. Delano’s salary of $225 yearly was raised to $300 in 1812, after a petition with 22 signatures was submitted on his behalf.

By 1810, the woodwork in the lighthouse and keeper’s house were in poor condition; the woodwork was damp and rotting. Part of the problem was that the keeper was storing a year’s supply of oil in one room, which putting great stress on the floor. Repairs were made, and an oil shed was added.

The tower continued to have problems with leaks. In November 1812, the contractor Winslow Lewis offered the opinion that the upper 20 feet of the tower was very poorly built. The lantern, which was only 5 feet in diameter, was also badly constructed. Lewis recommended reducing the tower’s height by 20 feet in height, along with the addition of a new lantern. Lewis carried out these changes in 1813, along with the installation of a system of lamps and reflectors designed by Lewis himself, at a cost of $2,100. About 25 feet of stonework at the top of the tower was removed.

The contractor Henry Dyer of Cape Elizabeth built a new keeper’s house in 1816 for $1,175. The one-story stone cottage was 20 by 34 feet, with and comprised two rooms, an attached kitchen, and an attic. The kitchen ell was attached to outbuildings, which, in turn, were joined to the tower. The joining of the house to the tower had been requested in 1809 by Delano, the keeper, who complained that the space between the buildings was often frozen over in winter and that the sea sometimes washed over the area.

Barzillai Delano died in 1820; his son, James Delano, later served as keeper from 1854 to 1861. Joshua Freeman, who would become known for his jovial hospitality, became keeper in 1820. Freeman kept a supply of rum and other spirits in a cupboard, and he’d sell it drinks for three cents a glass to visitors who came to fish. The top-shelf liquor was reserved for the local minister.

An 1825 article in the Eastern Argus described the pleasures of a visit to Portland Head:

I know of no excursion as pleasant as a jaunt to the Light House. There our friend Freeman is always at home, and ready to serve you. There you can angle in safety and comfort for the cunning cunner, while old ocean is rolling majestically at your feet, and when wearied and fatigued with this amusement, you will find a pleasant relaxation in tumbling the huge rocks from the brinks of the steep and rocky precipices. . . . I know of no equal to a ride or sail to the Light House and earnestly recommend it to all poor devils who, like myself, are afflicted with the dyspepsia, gout, or any of the diseases to which human flesh is heir.

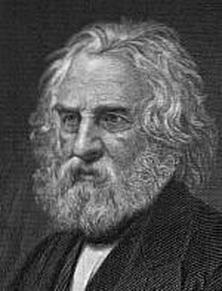

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was born in Portland, was a frequent visitor in his younger years. Longfellow's poem "The Lighthouse" was probably inspired by his many hours at Portland Head Light.

New lamps and reflectors were installed in 1850. in the following year, an inspection found much to be desired. The new reflectors were found to be badly scratched already. The house was leaky and cracking and the tower was being undermined by rats. The keeper was apparently poorly trained and had received no written instructions on the operation of the light. He had been forced to hire a man himself to train him for two days.

Improvements were made in the following years. A fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the lamps and reflectors in 1855. A fog bell tower with a 1,500-pound bell was installed, the tower was lined with brick, and a cast-iron spiral stairway was built.

Following the 1864 wreck of the Liverpool vessel Bohemian , in which 40 immigrants died, the light was further improved. The tower was raised 20 feet and a new second-order Fresnel lens was installed.

New lamps and reflectors were installed in 1850. in the following year, an inspection found much to be desired. The new reflectors were found to be badly scratched already. The house was leaky and cracking and the tower was being undermined by rats. The keeper was apparently poorly trained and had received no written instructions on the operation of the light. He had been forced to hire a man himself to train him for two days.

Improvements were made in the following years. A fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the lamps and reflectors in 1855. A fog bell tower with a 1,500-pound bell was installed, the tower was lined with brick, and a cast-iron spiral stairway was built.

Following the 1864 wreck of the Liverpool vessel Bohemian , in which 40 immigrants died, the light was further improved. The tower was raised 20 feet and a new second-order Fresnel lens was installed.

Captain Joshua Strout, a native of Cape Elizabeth and a former sea captain, became keeper in 1869 for $620 per year.

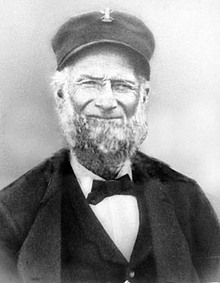

Joshua Strout (Museum at Portland Head Light)

Strout’s mother had worked as a housekeeper at Portland Head for Joshua Freeman in the 1820s, and she named her son for the keeper. Joshua Strout went to sea at the age of 11 and served as the cook on a tugboat by the time he was 18. He later captained a number of vessels and traveled as far as Cuba and South America. Injuries suffered in a severe fall from the masthead of the Andres forced him to give up his life at sea in exchange for the somewhat more tranquil life of a lighthouse keeper.

Strout's wife, Mary, became assistant keeper at a salary of $480 per year. She held the position until 1877, when her son Joseph took on the title of assistant keeper. Joshua and Mary Strout raised 11 children at the station.

A hurricane on September 8, 1869, knocked the fog bell into a ravine, nearly killing Joshua Strout. A new tower with a 2,000-pound bell and a Stevens striking mechanism was built the following year. The bell was soon replaced by a fog trumpet. In 1887, an engine for the fog signal was moved from Boston Light to Portland Head. An air-diaphragm chime horn was installed in 1938.

Strout's wife, Mary, became assistant keeper at a salary of $480 per year. She held the position until 1877, when her son Joseph took on the title of assistant keeper. Joshua and Mary Strout raised 11 children at the station.

A hurricane on September 8, 1869, knocked the fog bell into a ravine, nearly killing Joshua Strout. A new tower with a 2,000-pound bell and a Stevens striking mechanism was built the following year. The bell was soon replaced by a fog trumpet. In 1887, an engine for the fog signal was moved from Boston Light to Portland Head. An air-diaphragm chime horn was installed in 1938.

In 1910, Joseph Strout was quoted in the Lewiston Journal:

We've all got the lighthouse fever in our blood... Father was keeper before me. Joshua Freeman Strout, that was his name, and a fine old man he was too. He was named for Captain Joshua Freeman. He kept the light, too, Captain Freeman did, in the days when they burned whale oil and had sixteen lamps. When grandmother was a girl of sixteen, she worked at Cap'n Freeman's [she was his housekeeper] and after she married and father was born, she named him Joshua Freeman Strout. Old Cap'n Freeman used to sit in a big arm chair with a coil of rope near him so if a shipwreck came sudden he would be prepared.

Joseph Strout

A parrot named Billy was a well-known member of the Strout household at Portland Head for many years. When bad weather approached, Billy would tell Keeper Strout, "Joe, let's start the horn. It's foggy!" Billy reportedly became an avid fan of radio in his declining years and lived to be over 80.

In an 1898 interview, Joshua Strout said that he had gone as long as 17 years in a stretch without taking time off, and as long as two years without going as far as Portland. Strout, the oldest keeper on the Maine coast at the time, retired in 1904. He died three years later, at 80.

Joseph Strout became principal keeper in 1904. He remained until 1928, ending 59 years of the Strout family at Portland Head. In his 1935 book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them,Robert Thayer Sterling called Joseph Strout "one of the most popular lightkeepers of his day or any yet to come. His genial disposition, his hearty laugh, together with his good stories of the sea, won him the admiration of all who met him."

With the completion of Halfway Rock Light in 1871, the Lighthouse Board felt that Portland Head Light had become less important. The tower was shortened by 20 feet in 1883 and the second-order lens was replaced by a weaker fourth-order lens.

In an 1898 interview, Joshua Strout said that he had gone as long as 17 years in a stretch without taking time off, and as long as two years without going as far as Portland. Strout, the oldest keeper on the Maine coast at the time, retired in 1904. He died three years later, at 80.

Joseph Strout became principal keeper in 1904. He remained until 1928, ending 59 years of the Strout family at Portland Head. In his 1935 book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them,Robert Thayer Sterling called Joseph Strout "one of the most popular lightkeepers of his day or any yet to come. His genial disposition, his hearty laugh, together with his good stories of the sea, won him the admiration of all who met him."

With the completion of Halfway Rock Light in 1871, the Lighthouse Board felt that Portland Head Light had become less important. The tower was shortened by 20 feet in 1883 and the second-order lens was replaced by a weaker fourth-order lens.

This met with many complaints. A year later, the tower was restored to its former height and a second-order lens was again installed, first lighted January 15, 1885.

Circa 1880s

A new Victorian two-family keeper's house was built in 1891, on the same foundation as the 1816 one-story stone dwelling. The old stone house was reportedly moved to become a private home in Cape Cottage. The lighthouse station has changed very little since that time, except for a 1900 renovation during which many of the tower's stones were replaced.

In his 1876 book Portland and Vicinity, Edward H. Elwell reported that a few years earlier a party had gone to Portland Head to watch the crashing waves during a storm. Two carriage drivers who had brought the group out ventured too far out on the rocks and were swept away. Their bodies were recovered several days later.

On Christmas Eve, 1886, the British bark Annie C. Maguire ran ashore on the rocks at Portland Head. The Strouts got a ladder to the vessel and helped all aboard, including the captain's wife, make it safely to shore.

In his 1876 book Portland and Vicinity, Edward H. Elwell reported that a few years earlier a party had gone to Portland Head to watch the crashing waves during a storm. Two carriage drivers who had brought the group out ventured too far out on the rocks and were swept away. Their bodies were recovered several days later.

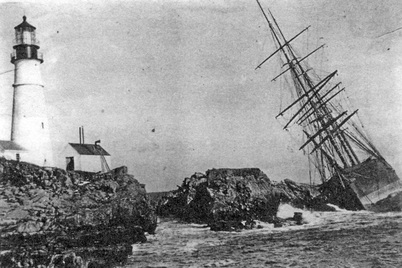

On Christmas Eve, 1886, the British bark Annie C. Maguire ran ashore on the rocks at Portland Head. The Strouts got a ladder to the vessel and helped all aboard, including the captain's wife, make it safely to shore.

On New Year's Day 1887, a storm destroyed the ship after everything of value had been removed. You can still see the rock near the lighthouse with the painted inscription: "Annie C. Maguire, shipwrecked here, Christmas Eve 1886."

The Annie C. Maguire (Museum at Portland Head Light)

Click here for more on the wreck of the Annie C. Maguire.

For a time, the buildings at Portland Head Light received serious damage from practice gunfire from neighboring Fort Williams. The U.S. Lighthouse Service Bulletin of September 1, 1916, reported that "windows were forced out, finish ripped off, roof torn open," and also reported "injury to the brickwork of the three chimneys of the double dwelling." On one occasion two of the chimneys were completely severed at the bottom. Casings were installed to protect the chimneys.

Frank O. Hilt became principal keeper in 1929. Hilt, who was originally from St. George, Maine, went to sea at a young age and eventually became the captain of the schooner Mary Langdon and other vessels. Beginning in 1913, he served as an assistant keeper and then principal keeper at the isolated light station at Matinicus Rock.

For a time, the buildings at Portland Head Light received serious damage from practice gunfire from neighboring Fort Williams. The U.S. Lighthouse Service Bulletin of September 1, 1916, reported that "windows were forced out, finish ripped off, roof torn open," and also reported "injury to the brickwork of the three chimneys of the double dwelling." On one occasion two of the chimneys were completely severed at the bottom. Casings were installed to protect the chimneys.

Frank O. Hilt became principal keeper in 1929. Hilt, who was originally from St. George, Maine, went to sea at a young age and eventually became the captain of the schooner Mary Langdon and other vessels. Beginning in 1913, he served as an assistant keeper and then principal keeper at the isolated light station at Matinicus Rock.

Hilt remained in charge at Portland Head until 1944. One of his more unusual accomplishments was the construction of a giant checkerboard near the base of the lighthouse tower.

Frank O. Hilt (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

Edward Rowe Snow, in his book The Romance of Casco Bay, wrote that one of his most delightful memories of Portland Head was photographing Hilt contemplating a move on the giant board during a checkers match with Snow’s wife, Anna-Myrle. Hilt “in his prime was a 300-pound giant,” according to Snow.

The last civilian keeper before the Coast Guard took over was Robert Thayer Sterling, a journalist who wrote the book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them in 1935.

Sterling, who was from Peaks Island in Portland, Maine, entered the Lighthouse Service in 1915 and spent time at Ram Island Ledge, Great Duck Island, Seguin Island, and Cape Elizabeth (Two Lights) before coming to arriving at Portland Head as an assistant in 1928. He succeeded Hilt as principal keeper in 1944.

The last civilian keeper before the Coast Guard took over was Robert Thayer Sterling, a journalist who wrote the book Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them in 1935.

Sterling, who was from Peaks Island in Portland, Maine, entered the Lighthouse Service in 1915 and spent time at Ram Island Ledge, Great Duck Island, Seguin Island, and Cape Elizabeth (Two Lights) before coming to arriving at Portland Head as an assistant in 1928. He succeeded Hilt as principal keeper in 1944.

Sterling, who retired in 1946, declared Portland Head the most desirable of all light stations for keepers. On the first day of his retirement, Sterling fell in his yard and broke a rib. As a result, he had to put his plans to attend some Boston Red Sox games on hold.

Right: Robert Thayer Sterling, principal keeper 1944-46. Courtesy of Maine Lighthouse Museum.

Sterling, who retired in 1946, declared Portland Head the most desirable of all light stations for keepers. On the first day of his retirement, Sterling fell in his yard and broke a rib. As a result, he had to put his plans to attend some Boston Red Sox games on hold.

Life at Portland Head Light was quite different from the popular image of the solitary lighthouse keeper. Constant tourists were a way of life. When Earle Benson was keeper in the 1950s, a woman walked right into the keeper's house and sat at the kitchen table. The woman insisted that Benson and his wife were government employees, and she demanded service.

Electricity came to Portland Head Light in 1929. The light was dark for three years during World War II. The second-order Fresnel lens was removed in 1958 and replaced by aerobeacons.

Severe weather has always plagued the station. In February 1972, Coast Guardsman Robert Allen reported to the Maine Sunday Telegram that a storm had torn the fog bell from its house, ripped 80 feet of steel fence out of concrete and left the house a "foot deep in mud and flotsam, including starfish." A wave had broken a window in the house 25 feet high.

Sterling, who retired in 1946, declared Portland Head the most desirable of all light stations for keepers. On the first day of his retirement, Sterling fell in his yard and broke a rib. As a result, he had to put his plans to attend some Boston Red Sox games on hold.

Life at Portland Head Light was quite different from the popular image of the solitary lighthouse keeper. Constant tourists were a way of life. When Earle Benson was keeper in the 1950s, a woman walked right into the keeper's house and sat at the kitchen table. The woman insisted that Benson and his wife were government employees, and she demanded service.

Electricity came to Portland Head Light in 1929. The light was dark for three years during World War II. The second-order Fresnel lens was removed in 1958 and replaced by aerobeacons.

Severe weather has always plagued the station. In February 1972, Coast Guardsman Robert Allen reported to the Maine Sunday Telegram that a storm had torn the fog bell from its house, ripped 80 feet of steel fence out of concrete and left the house a "foot deep in mud and flotsam, including starfish." A wave had broken a window in the house 25 feet high.

In a 1977 storm, the keeper and his family were evacuated. The power lines were downed and the generator burned out, leaving Portland Head Light dark for the first time since World War II.

Left: Portland Head Light during the hurricane of September 21, 1938.

On August 7, 1989, a celebration was held at Portland Head Light commemorating the 200th anniversary of the creation of the Lighthouse Service. The day also marked the automation of Portland Head Light and the removal of the Coast Guard keepers. Maine Senator George Mitchell, Congressman Joseph Brennan and lighthouse historian F. Ross Holland spoke at the celebration while the Nantucket Lightship paraded offshore with a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels.

Rear Admiral Richard Rybacki, the Coast Guard's First District commander, said in his address to the crowd, "I can think of nothing more noble. The lighthouse symbolizes all that is good in mankind. We are not here to celebrate an ending. We are here to immortalize a tradition."

The Museum at Portland Head Light opened in the former keeper's house in 1992. The museum focuses on the history of the lighthouse and nearby Fort Williams. Among the displays are the tower's old seven-foot-tall second order lens (right) and a fifth order lens from Squirrel Point. A garage was converted into a gift shop that now does about $500,000 worth of business yearly. (Note: The lighthouse tower is not open to the public, except on Maine Open Lighthouse Day in September.) In October 1993, the property was deeded to the Town of Cape Elizabeth.

On August 7, 1989, a celebration was held at Portland Head Light commemorating the 200th anniversary of the creation of the Lighthouse Service. The day also marked the automation of Portland Head Light and the removal of the Coast Guard keepers. Maine Senator George Mitchell, Congressman Joseph Brennan and lighthouse historian F. Ross Holland spoke at the celebration while the Nantucket Lightship paraded offshore with a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels.

Rear Admiral Richard Rybacki, the Coast Guard's First District commander, said in his address to the crowd, "I can think of nothing more noble. The lighthouse symbolizes all that is good in mankind. We are not here to celebrate an ending. We are here to immortalize a tradition."

The Museum at Portland Head Light opened in the former keeper's house in 1992. The museum focuses on the history of the lighthouse and nearby Fort Williams. Among the displays are the tower's old seven-foot-tall second order lens (right) and a fifth order lens from Squirrel Point. A garage was converted into a gift shop that now does about $500,000 worth of business yearly. (Note: The lighthouse tower is not open to the public, except on Maine Open Lighthouse Day in September.) In October 1993, the property was deeded to the Town of Cape Elizabeth.

For a few years, part of the keeper's house was rented as an apartment. The first tenants were two Coast Guard Ensigns, Matt Stuck and Sam Eisenbeiser.

The stairs in the tower

Ensign Stuck declared, "There's no other place on this planet with views out of every window." There was a downside, however. The ensigns told reporters that "the disadvantage of living at Portland Head Light is that you're part of the scenery," referring to the constant flow of tourists.

Ed and Elaine Amass then lived in the apartment for two years. "The view is worth the visitors and the foghorn. If it wasn't, we would have left the first year," said Ed Amass. The space is now used for storage for the museum and gift shop.

The all-volunteer Cape Elizabeth Garden Club maintains a beautiful flower garden near the lighthouse. The Exxon Corporation awarded the club third place in a national competition several years ago.

A $260,000 renovation was completed in the spring of 2005. Some repointing was done on the 80-foot tower and it was also repainted. The keeper's house and gift shop were also painted, and some of the lighthouse's windows were replaced.

Ed and Elaine Amass then lived in the apartment for two years. "The view is worth the visitors and the foghorn. If it wasn't, we would have left the first year," said Ed Amass. The space is now used for storage for the museum and gift shop.

The all-volunteer Cape Elizabeth Garden Club maintains a beautiful flower garden near the lighthouse. The Exxon Corporation awarded the club third place in a national competition several years ago.

A $260,000 renovation was completed in the spring of 2005. Some repointing was done on the 80-foot tower and it was also repainted. The keeper's house and gift shop were also painted, and some of the lighthouse's windows were replaced.

Some views from the top of the tower:

The Museum at Portland Head Light has welcomed visitors from every state in the United States and over 75 countries. The museum is open June through October.

Inside the Museum at Portland Head Light

There is ample parking and plenty of room for picnicking or strolling. The gate to Fort Williams Park, where the lighthouse is located, is open daily from sunrise to sunset. Maine's oldest lighthouse is easily accessible by land; some tour boats out of Portland approach the lighthouse by sea.

For more information, contact The Museum at Portland Head Light.

For more information, contact The Museum at Portland Head Light.

|

|

|

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at nelights@gmail.com. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Civilian principal keepers:

Joseph K. Greenleaf (1791-1795); Reuben Freeman (1795-1796); Barzillai Delano (1796-1820); Joshua Freeman (1820-1840); Richard Lee (1840-1849); John F. Watts (1849-1853); John W. Coolidge (1853-1854); James S. Williams (1854); James Delano (1854-1861); Elder M. Jordan (1861-1869); Joshua F. Strout (1869-1904); Joseph W. Strout (1904-1928); John W. Cameron (1928-1929); Frank. O. Hilt (1929-1944); Robert Thayer Sterling (1944-1946); William T. Burns (1954-1956)

Civilian assistant keepers:

Mary Strout (assistant, 1869-1877); Joseph W. Strout (1877-1904); Gil Strout (c. 1880s); John W. Cameron (assistant 1904-1928); John A. Strout (1912-1915); Millard Urquhart (c. 1928); Robert Thayer Sterling (1928-1944); William T. Burns (c. 1944-1954)

Coast Guard keepers:

William L. Lockhart (1946-1950); William F. Yost (c. 1950); Howard Beebe (1950-1951); Earle E. Benson (1952-1954); Edward Frank (c. 1956); Archie McLaughlin (1956-1957); Henry E. Leonard (1957-1960); Weston E. Gamage Jr. (c. 1960-1962); Stephen H. Rogers (c. 1960-1962); Armand Houde (March 1963-September 1965); Walter Dodge (1963); Thomas Reed (1966-1967); Franklin D. Allen (1968-1974); Kenneth A. Perry (c. 1973); Roy Cavanaugh (1974-1977); Anthony Di Nardi (c. 1975); Jerry Poliskey (c. 1977); Victor Bissonnette (1977-1978); Raymond Barbar (1978-1982); Gregory Clark (c. 1978); Marion P. Danna (1980-1983); Michael Cook (1982-1986); Nathan Wasserstrom (1986-1989); Davis Simpson (c. 1986-1989)

Civilian principal keepers:

Joseph K. Greenleaf (1791-1795); Reuben Freeman (1795-1796); Barzillai Delano (1796-1820); Joshua Freeman (1820-1840); Richard Lee (1840-1849); John F. Watts (1849-1853); John W. Coolidge (1853-1854); James S. Williams (1854); James Delano (1854-1861); Elder M. Jordan (1861-1869); Joshua F. Strout (1869-1904); Joseph W. Strout (1904-1928); John W. Cameron (1928-1929); Frank. O. Hilt (1929-1944); Robert Thayer Sterling (1944-1946); William T. Burns (1954-1956)

Civilian assistant keepers:

Mary Strout (assistant, 1869-1877); Joseph W. Strout (1877-1904); Gil Strout (c. 1880s); John W. Cameron (assistant 1904-1928); John A. Strout (1912-1915); Millard Urquhart (c. 1928); Robert Thayer Sterling (1928-1944); William T. Burns (c. 1944-1954)

Coast Guard keepers:

William L. Lockhart (1946-1950); William F. Yost (c. 1950); Howard Beebe (1950-1951); Earle E. Benson (1952-1954); Edward Frank (c. 1956); Archie McLaughlin (1956-1957); Henry E. Leonard (1957-1960); Weston E. Gamage Jr. (c. 1960-1962); Stephen H. Rogers (c. 1960-1962); Armand Houde (March 1963-September 1965); Walter Dodge (1963); Thomas Reed (1966-1967); Franklin D. Allen (1968-1974); Kenneth A. Perry (c. 1973); Roy Cavanaugh (1974-1977); Anthony Di Nardi (c. 1975); Jerry Poliskey (c. 1977); Victor Bissonnette (1977-1978); Raymond Barbar (1978-1982); Gregory Clark (c. 1978); Marion P. Danna (1980-1983); Michael Cook (1982-1986); Nathan Wasserstrom (1986-1989); Davis Simpson (c. 1986-1989)