History of Avery Rock Lighthouse, Machias, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

The town of Machias got its name from a local Native American word meaning “Little Bad River,” because of a small waterfall on the Machias River.

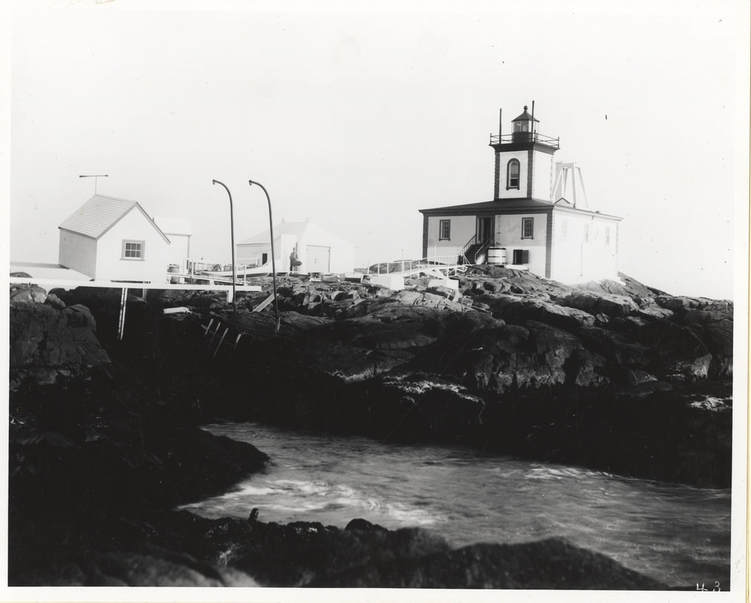

U.S. Coast Guard

The town has a sheltered harbor that led to its use as an early fur trading post and a hideout for pirates. In the 1800s, Machias developed into one of Maine’s leading lumber ports.

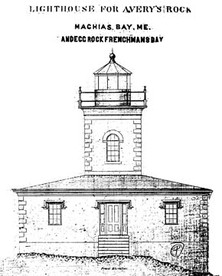

Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant authorized $15,000 for a lighthouse and fog signal on Avery Rock on June 23, 1874. The barren, exposed rock is at the south end of Machias Bay, about three miles from the mainland. After some delay, the federal government secured title to the site. A government pencil pusher who had obviously never seen tiny Avery Rock wrote that the conveyance of the site from the State of Maine was not to include “any public or private burying ground, dwelling houses, or meeting house . . . or any highway.”

Work began early in 1875, but rough seas caused delays in the project. The rock encompasses only about a quarter of an acre, so the square, wooden lighthouse tower, 12 feet wide on each side, was built on the roof of the brick dwelling to save space. A 1,200-pound fog bell with automatic striking machinery was installed in a pyramidal wooden tower next to the dwelling.

Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant authorized $15,000 for a lighthouse and fog signal on Avery Rock on June 23, 1874. The barren, exposed rock is at the south end of Machias Bay, about three miles from the mainland. After some delay, the federal government secured title to the site. A government pencil pusher who had obviously never seen tiny Avery Rock wrote that the conveyance of the site from the State of Maine was not to include “any public or private burying ground, dwelling houses, or meeting house . . . or any highway.”

Work began early in 1875, but rough seas caused delays in the project. The rock encompasses only about a quarter of an acre, so the square, wooden lighthouse tower, 12 feet wide on each side, was built on the roof of the brick dwelling to save space. A 1,200-pound fog bell with automatic striking machinery was installed in a pyramidal wooden tower next to the dwelling.

The station went into service on October 15, 1875, with a fifth-order Fresnel lens exhibiting a white flash every six seconds, 54 feet above mean high water. The station was always home to one keeper and his family; the first keeper was Charles F. Chase, who was 67 years old when he took the job. Chase stayed until 1880.

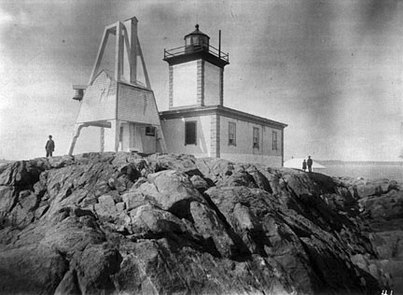

Avery Rock Light in 1892.

U.S. Coast Guard photo

Mary Bradford Crowninshield's 1886 book All Among the Lighthouses described the station:

Avery’s Rock, though but an immense granite boulder rising up out of the sea, is not so far from the mainland but that an easy sail takes the keeper to the post-office. And the mail seems to be the greatest solace to these lonely people. The keeper’s dwelling . . . was . . . redolent with the fragrance of flowers, for the windows were filled with boxes and pots of every description.

A boathouse and a 50-foot-long boat slip were added to the station in 1885. After a great storm in January 1891 carried away the boathouse, it was rebuilt. A new bell tower, made of yellow pine, was erected at the same time, securely bolted to the ledge and connected to the dwelling by a covered wooden passageway. Five hundred square feet of heavy timbers were bolted to the ledge in front of the dwelling and at its corners to afford more protection from the sea.

Another timber bulkhead was added on the east side of the rock in 1895, and heavy shutters were attached to the dwelling. The Lighthouse Board asked for an appropriation of $1,700 in 1899 to add a second story to the dwelling, but this improvement never came to pass.

Avery’s Rock, though but an immense granite boulder rising up out of the sea, is not so far from the mainland but that an easy sail takes the keeper to the post-office. And the mail seems to be the greatest solace to these lonely people. The keeper’s dwelling . . . was . . . redolent with the fragrance of flowers, for the windows were filled with boxes and pots of every description.

A boathouse and a 50-foot-long boat slip were added to the station in 1885. After a great storm in January 1891 carried away the boathouse, it was rebuilt. A new bell tower, made of yellow pine, was erected at the same time, securely bolted to the ledge and connected to the dwelling by a covered wooden passageway. Five hundred square feet of heavy timbers were bolted to the ledge in front of the dwelling and at its corners to afford more protection from the sea.

Another timber bulkhead was added on the east side of the rock in 1895, and heavy shutters were attached to the dwelling. The Lighthouse Board asked for an appropriation of $1,700 in 1899 to add a second story to the dwelling, but this improvement never came to pass.

In 1902, the light was upgraded with the installation of a fourth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed red light. Yet another bulkhead of hard pine was added in the same year to protect the boat slip.

Edward T. Spurling became keeper in 1899. In an interview many years later, his daughter Beatrice recalled life at the station:

Avery Rock had no vegetation whatsoever. It must have seemed lonely for my mother, at first, but with a growing family she had plenty to take up her mind. There were heavy shutters on all the windows. In a gale, at high tide, the seas would wash right over the rock. But we always felt safe and snug inside with every confidence in Father, whose calm always made us feel safe.

According to Beatrice, a 1900 storm obliterated the sight of the lighthouse from the mainland, and local residents thought the station had been swept from the rock. It turned out that everything was fine.

Left: Edward T. Spurling. Courtesy of Danny Harrison and Fort Point State Park/Terry Cole.

On another occasion, on a moonlit night, a schooner went aground at the rock and its jib boom nearly crashed through a bedroom window. The crew safely evacuated onto the island, where Spurling and his wife cared for them until they were able to refloat the schooner at high tide.

Josiah Larrabee became keeper in 1905. His six-year-old son Maurice died tragically in the summer of 1907 when he fell into a gulch near the lighthouse and drowned.

Avery Rock had no vegetation whatsoever. It must have seemed lonely for my mother, at first, but with a growing family she had plenty to take up her mind. There were heavy shutters on all the windows. In a gale, at high tide, the seas would wash right over the rock. But we always felt safe and snug inside with every confidence in Father, whose calm always made us feel safe.

According to Beatrice, a 1900 storm obliterated the sight of the lighthouse from the mainland, and local residents thought the station had been swept from the rock. It turned out that everything was fine.

Left: Edward T. Spurling. Courtesy of Danny Harrison and Fort Point State Park/Terry Cole.

On another occasion, on a moonlit night, a schooner went aground at the rock and its jib boom nearly crashed through a bedroom window. The crew safely evacuated onto the island, where Spurling and his wife cared for them until they were able to refloat the schooner at high tide.

Josiah Larrabee became keeper in 1905. His six-year-old son Maurice died tragically in the summer of 1907 when he fell into a gulch near the lighthouse and drowned.

Charles Allen became keeper in 1913. Allen was married to Minnie (Scovill), the sister of Connie Small, author of the popular book The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife. Their daughter, Beulah, in an interview many years later, described the family’s arrival at Avery Rock: “It was during a storm; the boat was rocking and rolling, and we were sliding from one end of the boat to the other.”

Connie and Elson Small in 1921

Beulah attended school on the mainland when she was seven years old. Later, a teacher would visit the island for a week or so and assign two or three months of lessons at a time.

One night, Charles Allen went to bed after winding the clockwork mechanism that ran the fog bell striker. A cable snapped and the weights crashed to the bottom of the bell tower. According to Beulah, her father probably would have been killed if he had been in the tower. The mechanism wasn’t fixed for about a week, and in the interim Charles Allen had to ring the fog bell by hand for over 200 hours.

Connie Small's book, The Lighthouse Keeper's Wife, describes her life at several lighthouses with her husband, Keeper Elson Small. The Smalls came to Avery Rock in 1922. To make sure they had enough to eat in the winter, Connie did a great deal of canning of vegetables. Her husband hunted for wild ducks near the rock and dug clams on a nearby island. There was no soil on the barren rock, but in the summer the Smalls would bring loam from another island and plant a long box of marigolds, geraniums, and petunias.

Connie learned to operate the light and fog bell so she could fill in when her husband was on the mainland. One day, Connie was alone when the fog bell stopped sounding in a snowstorm.

One night, Charles Allen went to bed after winding the clockwork mechanism that ran the fog bell striker. A cable snapped and the weights crashed to the bottom of the bell tower. According to Beulah, her father probably would have been killed if he had been in the tower. The mechanism wasn’t fixed for about a week, and in the interim Charles Allen had to ring the fog bell by hand for over 200 hours.

Connie Small's book, The Lighthouse Keeper's Wife, describes her life at several lighthouses with her husband, Keeper Elson Small. The Smalls came to Avery Rock in 1922. To make sure they had enough to eat in the winter, Connie did a great deal of canning of vegetables. Her husband hunted for wild ducks near the rock and dug clams on a nearby island. There was no soil on the barren rock, but in the summer the Smalls would bring loam from another island and plant a long box of marigolds, geraniums, and petunias.

Connie learned to operate the light and fog bell so she could fill in when her husband was on the mainland. One day, Connie was alone when the fog bell stopped sounding in a snowstorm.

She knew how to wind the clockwork mechanism that powered the bell striker, but this time she found that a pin had fallen out of the machinery.

Courtesy of Connie Small

Connie had no training in the workings of the mechanism, so she rang the bell manually by pulling the rope for 90 minutes.

After her hands became too blistered to continue, she managed to determine the pin’s proper place. She soon had the bell sounding again. Connie later explained, “I might not have been qualified to do something and yet I had to do it. So I got used to it.” Once, when Elson Small was ill with a high fever, Connie Small kept the light and fog bell on her own for 15 days.

After her hands became too blistered to continue, she managed to determine the pin’s proper place. She soon had the bell sounding again. Connie later explained, “I might not have been qualified to do something and yet I had to do it. So I got used to it.” Once, when Elson Small was ill with a high fever, Connie Small kept the light and fog bell on her own for 15 days.

|

In this clip from an interview recorded when Connie Small was 96 years old, she describes life at Avery Rock -- including a near tragedy.

|

In this clip, Connie Small recalls her husband's serious illness during their stay at Avery Rock.

|

Avery Rock was completely exposed to the elements. On January 25-26, 1928, a fierce storm struck while Edwin Pettegrow was keeper.

The bell tower on Avery Rock took a beating in a storm in January 1928, as the photo to the right shows.

[Note: Some sources say the storm was in 1926, some say 1928.]

An article by Richard Hallett later described Pettegrow’s ordeal:

It had smashed in the front of the house, where the windows were protected by solid two-inch plank shutters, and then had filled the house itself drowningful of water.

“Tide was coming in against the wind,” Pettegrow said. “I said to myself, if the wind cants to the southwest, it’s all over with us. The lower the tide dropped, the farther it had to jump back, it seemed like. It got more of a run for it.”

At the height of everything, with the air itself half water, the bell hammer had stuck. Even Thor’s hammer would have got hung up in the midst of such ructions. Pettegrow had to stand back of the bell hammer all night, and nudge it to induce it to strike. Meanwhile the iron bedsteads in the west bedroom were getting twisted into true-lover’s knots by the force of the water coming into the house through broken windows; plaster was falling from walls and ceilings; and Pettegrow, between spells of nudging the bell hammer, was on his knees with an auger, boring holes in the floors to let the water drain out. A man wouldn’t believe the wind could blow so hard. Pettegrow took a sheep into the house to save it and then had to hang onto its wool to keep from going by the board himself. High overhead, the light winked on. “We saved the light out of the wreck,” Pettegrow said.

The storm lasted three days. Pettegrow’s wife and mother spent virtually its entire duration huddled by the kitchen stove.

The lighthouse was converted to automatic acetylene operation in 1934. A Coast Guard report in 1946 indicated that the lighthouse and other structures had “deteriorated beyond reasonable repair.”

The buildings were offered at auction, with the stipulation that the buyer had to remove them from the island; there were no takers. A work party razed what was left of the light station’s structures in 1947, and the light was relocated to a steel skeleton tower.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Charles F. Chase (1875-1880); Thomas E. Dodge (1880-1883); Joseph M. Gordan (1883); John W. Guptill (1883-1890); John Connors (1890-1894); Warren A. Murch (1894-1899); Edward T. Spurling (1899-1901); John B. Thurston (1901-?); Josiah Larrabee (1905-?); Charles W. Allen (1913-1922); Elson Small (1922-1926); Edwin Pettegrow (or Pettegrew) (1926-1933).

[Note: Some sources say the storm was in 1926, some say 1928.]

An article by Richard Hallett later described Pettegrow’s ordeal:

It had smashed in the front of the house, where the windows were protected by solid two-inch plank shutters, and then had filled the house itself drowningful of water.

“Tide was coming in against the wind,” Pettegrow said. “I said to myself, if the wind cants to the southwest, it’s all over with us. The lower the tide dropped, the farther it had to jump back, it seemed like. It got more of a run for it.”

At the height of everything, with the air itself half water, the bell hammer had stuck. Even Thor’s hammer would have got hung up in the midst of such ructions. Pettegrow had to stand back of the bell hammer all night, and nudge it to induce it to strike. Meanwhile the iron bedsteads in the west bedroom were getting twisted into true-lover’s knots by the force of the water coming into the house through broken windows; plaster was falling from walls and ceilings; and Pettegrow, between spells of nudging the bell hammer, was on his knees with an auger, boring holes in the floors to let the water drain out. A man wouldn’t believe the wind could blow so hard. Pettegrow took a sheep into the house to save it and then had to hang onto its wool to keep from going by the board himself. High overhead, the light winked on. “We saved the light out of the wreck,” Pettegrow said.

The storm lasted three days. Pettegrow’s wife and mother spent virtually its entire duration huddled by the kitchen stove.

The lighthouse was converted to automatic acetylene operation in 1934. A Coast Guard report in 1946 indicated that the lighthouse and other structures had “deteriorated beyond reasonable repair.”

The buildings were offered at auction, with the stipulation that the buyer had to remove them from the island; there were no takers. A work party razed what was left of the light station’s structures in 1947, and the light was relocated to a steel skeleton tower.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Charles F. Chase (1875-1880); Thomas E. Dodge (1880-1883); Joseph M. Gordan (1883); John W. Guptill (1883-1890); John Connors (1890-1894); Warren A. Murch (1894-1899); Edward T. Spurling (1899-1901); John B. Thurston (1901-?); Josiah Larrabee (1905-?); Charles W. Allen (1913-1922); Elson Small (1922-1926); Edwin Pettegrow (or Pettegrew) (1926-1933).