History of Stamford Harbor Lighthouse, Stamford, Connecticut

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

Even on a bright summer's day the lighthouse seems isolated, remote and lonely. By night and in a raging storm it is a place to try the steadiest nerves. - New York Herald, August 16, 1908.

U.S. Coast Guard

Stamford, settled in the 1640s, grew in importance in the late 1800s when New York City investors were enticed to develop industries in the area. The entrance to Stamford Harbor is obstructed by treacherous reefs. Local mariners had petitioned for a lighthouse as far back as 1871, but it wasn't until 1880 and 1881 that a total of $30,000 was appropriated.

The construction of Stamford Harbor Light began in 1881. The sections of the cast-iron tower were manufactured at a Boston foundry, then assembled on a cylindrical pier, 28 feet high and 30 feet in diameter, at Chatham Ledge.

The finished tower, 3,600 feet from shore, was a fairly typical "sparkplug" style lighthouse of the era. The iron pier, lined with brick, later served as storage for water, coal and oil. The lighthouse had seven levels in all.

Stamford Harbor Light originally had a fourth-order Fresnel lens and was equipped with a foghorn. The lighthouse went into service on February 10, 1882. Neil Martin was the first keeper; he remained less than a year before moving on to Penfield Reef Light.

Naylor Jones was the second keeper. After a dock and chicken coop he had built were washed out to sea in a storm along with the station's boat, Keeper Jones elected to live on shore with his family and travelled back and forth to the lighthouse in a rowboat. Jones' successors lived at the lighthouse, sometimes with their families. A baby was born at the lighthouse to Keeper Robert M. Fitton and his wife in 1929.

The construction of Stamford Harbor Light began in 1881. The sections of the cast-iron tower were manufactured at a Boston foundry, then assembled on a cylindrical pier, 28 feet high and 30 feet in diameter, at Chatham Ledge.

The finished tower, 3,600 feet from shore, was a fairly typical "sparkplug" style lighthouse of the era. The iron pier, lined with brick, later served as storage for water, coal and oil. The lighthouse had seven levels in all.

Stamford Harbor Light originally had a fourth-order Fresnel lens and was equipped with a foghorn. The lighthouse went into service on February 10, 1882. Neil Martin was the first keeper; he remained less than a year before moving on to Penfield Reef Light.

Naylor Jones was the second keeper. After a dock and chicken coop he had built were washed out to sea in a storm along with the station's boat, Keeper Jones elected to live on shore with his family and travelled back and forth to the lighthouse in a rowboat. Jones' successors lived at the lighthouse, sometimes with their families. A baby was born at the lighthouse to Keeper Robert M. Fitton and his wife in 1929.

John J. Cook, originally from Denmark, was the keeper from 1907 to 1909. In May 1908, a newspaper story with the headline “Heroine Passes Night of Terror” told a genuinely harrowing tale.

Keeper John J. Cook

Cook’s mother-in-law, Louisa Weickman, was living at the lighthouse with her daughter Martha and Keeper Cook that spring.

Martha was feeling ill and left to spend some time on shore with friends. After some days had passed, word came back to the lighthouse that she was anxious to return and Cook set out in the station’s 15-foot motor launch to pick her up.

Cook picked up his wife onshore and headed back for the lighthouse in the afternoon. The wind picked up from the northwest, and at about 5:30 Mrs. Weickman saw the boat approaching. Cook was struggling against the wind and tide and the boat was briefly hung up on a rock.

The keeper got out in knee-high water and shoved the boat off, but another landing attempt was unsuccessful. Pushing off from another rock, Cook lost one of his two oars in the water.

“We’ll go back to shore and come out when this is over,” shouted the keeper to his mother-in-law. “You keep the light going.”

Martha was feeling ill and left to spend some time on shore with friends. After some days had passed, word came back to the lighthouse that she was anxious to return and Cook set out in the station’s 15-foot motor launch to pick her up.

Cook picked up his wife onshore and headed back for the lighthouse in the afternoon. The wind picked up from the northwest, and at about 5:30 Mrs. Weickman saw the boat approaching. Cook was struggling against the wind and tide and the boat was briefly hung up on a rock.

The keeper got out in knee-high water and shoved the boat off, but another landing attempt was unsuccessful. Pushing off from another rock, Cook lost one of his two oars in the water.

“We’ll go back to shore and come out when this is over,” shouted the keeper to his mother-in-law. “You keep the light going.”

Mrs. Weickman watched the little boat drift away, but then a steamer passed by and she lost sight of the launch.

Louisa Weickman

She feared that they had been struck and killed by the steamer. “I have known a lot of sorrow,” she said, “but I don’t think I ever suffered so much as that night. I was powerless to do anything. . . . All I could do was watch, pray and hope.”

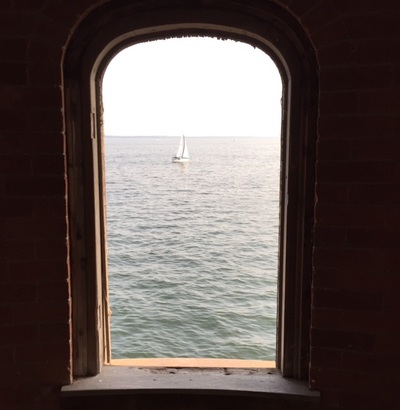

Despite her anxiety, Mrs. Weickman lit the lighthouse lamp at sunset and sat by one of the tower’s windows. She stayed at the window all night. “Sleep I did not dream of,” she said, “food I did not want.”

The next day passed with no word. Finally, about 10:00 that night, a man came near the lighthouse in a boat and told Mrs. Weickman that Martha and John had been picked up on Long Island.

Despite her anxiety, Mrs. Weickman lit the lighthouse lamp at sunset and sat by one of the tower’s windows. She stayed at the window all night. “Sleep I did not dream of,” she said, “food I did not want.”

The next day passed with no word. Finally, about 10:00 that night, a man came near the lighthouse in a boat and told Mrs. Weickman that Martha and John had been picked up on Long Island.

They had gone ashore near Eaton’s Neck, and a surfman from the Eaton’s Neck Life-Saving Station found the empty boat.

1935 U.S. Coast Guard photo by R. C. Smith

He subsequently encountered Keeper Cook plodding down the beach, carrying his weakened wife in his arms. Cook was concerned that the light might have gone out in the lighthouse, posing a danger to navigation. But the lifesaving station crew contacted someone in Stamford and learned that the light had not failed. The family was soon reunited. “My prayers are answered,” said Mrs. Weickman.

In 1908, Keeper Cook was interviewed for a newspaper article. When asked what it was like being in the lighthouse at Christmas, Cook responded:

I dunno; it is pretty lonesome out here sometimes, especially in winter, but we manage to enjoy our holidays. We can't go to church on Christmas, and we miss the nice music and the fine sermons, but there is a compensation for that. What more soul-stirring music could there be than that of wind and wave as they whistle and roar or moan and swish past our little home? And that light up aloft is a sermon in itself.

The Coast Guard discontinued Stamford Harbor Light as an official aid to navigation in 1953. The lighthouse, which retained a weaker automatic light as a private aid to navigation, was offered for sale, but the bids were few and far between.

The tower finally was sold for $1 in 1955 to Thomas F. Quigley, former mayor of Stamford. Quigley wanted to make the lighthouse a historic landmark. Nothing was done for the deteriorating structure, and in 1964 ownership reverted to the General Services Administration.

It was then sold to the Hartford Electric Light Company, then in 1982 to the Connecticut Light and Power Company. In 1984, Eryk Spektor, Chairman of the Board of the First Women's Bank, New York City, bought Stamford Harbor Light for $230,000. "I wanted a lighthouse," said Spektor. "It'll be a cheap place to park my boat."

Spektor spent $300,000 renovating the lighthouse. A new kitchen was added and the interior was paneled and painted. A small breakwater and dock were built for Spektor's boat. Spektor never actually stayed at the lighthouse, however, because his wife refused to spend a night there.

Mr. Spektor died in December 1998. The Lighthouse was sold by his family in August 2023 to the Stamford Harbor Lighthouse Project, a tax exempt 501c3 organization founded by Dr. Gary Kalan and Mr. Brendan McGee. They are raising funds to restore the lighthouse and to maintain it as an environmental and educational facility.

The lighthouse can be viewed from spots along the shore, but it is best seen by private boat. Stamford Harbor Light remains an active private aid to navigation.

In 1908, Keeper Cook was interviewed for a newspaper article. When asked what it was like being in the lighthouse at Christmas, Cook responded:

I dunno; it is pretty lonesome out here sometimes, especially in winter, but we manage to enjoy our holidays. We can't go to church on Christmas, and we miss the nice music and the fine sermons, but there is a compensation for that. What more soul-stirring music could there be than that of wind and wave as they whistle and roar or moan and swish past our little home? And that light up aloft is a sermon in itself.

The Coast Guard discontinued Stamford Harbor Light as an official aid to navigation in 1953. The lighthouse, which retained a weaker automatic light as a private aid to navigation, was offered for sale, but the bids were few and far between.

The tower finally was sold for $1 in 1955 to Thomas F. Quigley, former mayor of Stamford. Quigley wanted to make the lighthouse a historic landmark. Nothing was done for the deteriorating structure, and in 1964 ownership reverted to the General Services Administration.

It was then sold to the Hartford Electric Light Company, then in 1982 to the Connecticut Light and Power Company. In 1984, Eryk Spektor, Chairman of the Board of the First Women's Bank, New York City, bought Stamford Harbor Light for $230,000. "I wanted a lighthouse," said Spektor. "It'll be a cheap place to park my boat."

Spektor spent $300,000 renovating the lighthouse. A new kitchen was added and the interior was paneled and painted. A small breakwater and dock were built for Spektor's boat. Spektor never actually stayed at the lighthouse, however, because his wife refused to spend a night there.

Mr. Spektor died in December 1998. The Lighthouse was sold by his family in August 2023 to the Stamford Harbor Lighthouse Project, a tax exempt 501c3 organization founded by Dr. Gary Kalan and Mr. Brendan McGee. They are raising funds to restore the lighthouse and to maintain it as an environmental and educational facility.

The lighthouse can be viewed from spots along the shore, but it is best seen by private boat. Stamford Harbor Light remains an active private aid to navigation.

Below: Photos of the interior of the lighthouse in 2015, courtesy of Jim Troy.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at[email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Neil Martin (1882); Naylor (Nahor?) Jones (1882-1886); Samuel C. Gardiner (1886); John Ryle (1886-1887); Samuel A. Keeney (1887-1903); Maurice Russell (1903-1904); Adolph Obman (1904-1907 and 1909-1911); John J. Cook (1907-1909); W. Janse (?) (1909); Robert R. Laurier (1911-1912); John H. Paul (1912-?); George Washington Benton Jr. (c. 1919); James E. Smith (c. 1919-1920); Rudolph Iten (c. 1926-1929); Robert M. Fitton (c. 1929); Edward Whitford (c. 1929); Raymond Bliven (?-1931, died in service); Andrew A. McLintock (1937-1942?); Marty L. Sowle (1938-1953); Willard Riley (lamplighter, 1953-?)

Neil Martin (1882); Naylor (Nahor?) Jones (1882-1886); Samuel C. Gardiner (1886); John Ryle (1886-1887); Samuel A. Keeney (1887-1903); Maurice Russell (1903-1904); Adolph Obman (1904-1907 and 1909-1911); John J. Cook (1907-1909); W. Janse (?) (1909); Robert R. Laurier (1911-1912); John H. Paul (1912-?); George Washington Benton Jr. (c. 1919); James E. Smith (c. 1919-1920); Rudolph Iten (c. 1926-1929); Robert M. Fitton (c. 1929); Edward Whitford (c. 1929); Raymond Bliven (?-1931, died in service); Andrew A. McLintock (1937-1942?); Marty L. Sowle (1938-1953); Willard Riley (lamplighter, 1953-?)