History of Lime Rock Light, Newport, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

The history of the Lime Rock Light Station in Newport Harbor is inseparable from the story of its famous keeper. Idawalley Zoradia Lewis is the most celebrated lighthouse keeper in American history.

Ida Lewis

By the middle of the nineteenth century, passenger ferries, commercial traffic, and military personnel heading to and from Fort Adams combined to necessitate a navigational light in Newport's inner harbor. Congress appropriated the modest amount of $1,000 for a light on March 3, 1853.

During the following year, a small stone tower was erected on the largest of the Lime Rocks, a cluster of limestone ledges about 900 feet from shore, on the southern side of the inner harbor. At first, the keeper had to row from shore to tend the light. A one-room shanty was provided near the tower in case bad weather forced the keeper to spend the night.

Hosea Lewis was appointed keeper on November 15, 1853. Lewis, a native of Hingham, Massachusetts, was born in 1804 and went to sea at an early age. He had served as a pilot in the Revenue Cutter service for about 12 years when he took the lightkeeping job.

Lewis lived with his family in a small house at the corner of Spring and Brewery streets in Newport. His first wife had died, and Lewis married Idawalley Zoradia Willey, daughter of a prominent Block Island physician, in 1838. Their first son, Horatio, died at the age of 10.

During the following year, a small stone tower was erected on the largest of the Lime Rocks, a cluster of limestone ledges about 900 feet from shore, on the southern side of the inner harbor. At first, the keeper had to row from shore to tend the light. A one-room shanty was provided near the tower in case bad weather forced the keeper to spend the night.

Hosea Lewis was appointed keeper on November 15, 1853. Lewis, a native of Hingham, Massachusetts, was born in 1804 and went to sea at an early age. He had served as a pilot in the Revenue Cutter service for about 12 years when he took the lightkeeping job.

Lewis lived with his family in a small house at the corner of Spring and Brewery streets in Newport. His first wife had died, and Lewis married Idawalley Zoradia Willey, daughter of a prominent Block Island physician, in 1838. Their first son, Horatio, died at the age of 10.

Their second child, born February 25, 1842, was named Idawalley Zoradia Lewis, but she would be known to the world as "Ida."

An early engraving of Newport Harbor and Lime Rock

In 1857, a keeper's house was built at the station. The hip-roofed brick house with two stories was similar to the dwellings finished at Beavertail, Watch Hill, and Dutch Island around the same time. A narrow, square column of brick built into the building's northwest corner was surmounted by a small lantern, which held a sixth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed white light. Access to the lens was through a second-story alcove in the house.

The Lewis family moved to their new offshore home in late June. About four months later, Hosea Lewis suffered a paralyzing stroke that left him unable to fulfill his duties as keeper. His wife took over much of the lighthouse work and was eventually given the official title of keeper in 1872. But right from the time of her father's stroke, young Ida played a substantial role in the management of the light and household.

The Lewis family moved to their new offshore home in late June. About four months later, Hosea Lewis suffered a paralyzing stroke that left him unable to fulfill his duties as keeper. His wife took over much of the lighthouse work and was eventually given the official title of keeper in 1872. But right from the time of her father's stroke, young Ida played a substantial role in the management of the light and household.

By the age of 14 Ida had become known as the best swimmer in Newport.

Ida not only tended the light but also rowed her younger brothers and sisters to the mainland every day for school and picked up supplies as they were needed. Ida's rowing skills, strength, and courage were to come into play many times during her life at Lime Rock. Officially, she's credited with 18 lives saved, but the number was possibly as high as 35-the modest Ms. Lewis kept no records of her lifesaving exploits.

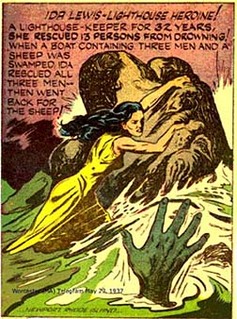

Right: This drawing originally portrayed Grace Darling, English lighthouse heroine, but it was used in American publications to represent Ida Lewis.

Her first rescue was in the fall of 1858, when she was only 16. On a cold, dreary day, four local young men were sailing back and forth between Fort Adams and the Lime Rocks. Ida watched from a window as one of the youths climbed the mast and began deliberately rocking the boat back and forth, probably to scare his friends. Scare them he did, but his tactic proved too successful when the sailboat capsized. The boat was soon keel up, with the four young men desperately struggling to stay afloat alongside. Ida rushed to the scene in her small boat and hauled the four aboard one at a time. They were taken to the lighthouse, where they soon recovered. The incident received no attention at the time.

Right: This drawing originally portrayed Grace Darling, English lighthouse heroine, but it was used in American publications to represent Ida Lewis.

Her first rescue was in the fall of 1858, when she was only 16. On a cold, dreary day, four local young men were sailing back and forth between Fort Adams and the Lime Rocks. Ida watched from a window as one of the youths climbed the mast and began deliberately rocking the boat back and forth, probably to scare his friends. Scare them he did, but his tactic proved too successful when the sailboat capsized. The boat was soon keel up, with the four young men desperately struggling to stay afloat alongside. Ida rushed to the scene in her small boat and hauled the four aboard one at a time. They were taken to the lighthouse, where they soon recovered. The incident received no attention at the time.

Ida later said that she "did not think the matter worth talking about and never gave it a second thought."

Nearly eight years passed before Ida's next recorded rescue. In February 1866, three soldiers were walking back to Fort Adams after some serious downtown imbibing. The men saw an old skiff, belonging to one of Ida's brothers, tied up at a wharf along the waterfront, and decided that they were entitled to commandeer the boat to shorten their trip to the fort. As they reached deep water in the flimsy skiff, one of the drunken men put his foot right through the floor.

Two of the men were never heard from again. Their bodies were never found, and it isn't clear if they drowned or deserted. But the third man drifted helplessly in the sinking skiff until Ida arrived. Although strong and agile, Ida was not a big woman, and she had to struggle mightily to pull the half-drowned soldier into her boat. It took her months to recover from the strain.

Early in 1867, three men were walking along the Newport shore, transporting a valuable sheep that belonged to wealthy banker August Belmont. The sheep suddenly decided to make an escape. Despite a harsh southeast wind and heavy seas, the animal dove into the harbor and swam for all it was worth. The men found a new skiff belonging to Ida's brother and launched it in hot pursuit.

Two of the men were never heard from again. Their bodies were never found, and it isn't clear if they drowned or deserted. But the third man drifted helplessly in the sinking skiff until Ida arrived. Although strong and agile, Ida was not a big woman, and she had to struggle mightily to pull the half-drowned soldier into her boat. It took her months to recover from the strain.

Early in 1867, three men were walking along the Newport shore, transporting a valuable sheep that belonged to wealthy banker August Belmont. The sheep suddenly decided to make an escape. Despite a harsh southeast wind and heavy seas, the animal dove into the harbor and swam for all it was worth. The men found a new skiff belonging to Ida's brother and launched it in hot pursuit.

The wind-whipped waves quickly swamped the little boat, and the men found themselves fighting to stay alive. Always alert, Ida sprung into action and rescued all three.

After the men were safely at the lighthouse, Ida saw the sheep, fighting against the waves to reach shore. She rowed back out, got a rope around the animal, and hauled it to safety.

Ida's most famous rescue occurred about two years later. On March 29, 1869 two soldiers were passing through Newport Harbor towards Fort Adams in a small boat. The men, Sgt. James Adams and Pvt. John McLaughlin, had enlisted the help of a 14-year-old boy who claimed to know his way through the harbor.

A snowstorm was churning the harbor's waters, and the boat was soon overturned. The two soldiers clung to their overturned boat, but the boy was lost in the icy water. Ida's mother saw their predicament and called to Ida, who was suffering from a cold.

Ida ran to her boat without taking the time to put on a coat or shoes. With the help of her younger brother, Ida was able to haul the two men into her boat and bring them to the lighthouse. One of the men later gave a gold watch to Ida, and for her heroism she became the first woman to receive a gold Congressional medal for lifesaving. The soldiers at Fort Adams showed their appreciation by collecting $218 for Ida.

Years later, Ida recalled this rescue.

I don't know if I was ever afraid. I just went, and that was all there was to it. Now my mother, she wasn't like me. That night when the two soldiers were tipped out of their boat, I was sitting there with my feet in the oven. I had a bad cold. But when I heard those men calling, I started right out, just as I was, with a towel over my shoulders, and mother begged me not to go. She was so nervous that she nearly fainted away while I was out there. But then, she was sickly quite a time. It was my father who showed me how to take people into my boat. You have to draw them over the stern or they will tip you over.

In the Fourth of July parade in 1869, the citizens of Newport presented Ida with a new mahogany boat named Rescue. Ida declined to make a speech. Her reaction as the crowd cheered was simply, "Thank you. Thank you-I don't deserve it."

The boat -- complete with gold-plated oarlocks and red velvet cushions -- was put on wheels for the parade, and Ida rode it past throngs of admirers lining the streets of the city.

Ida's most famous rescue occurred about two years later. On March 29, 1869 two soldiers were passing through Newport Harbor towards Fort Adams in a small boat. The men, Sgt. James Adams and Pvt. John McLaughlin, had enlisted the help of a 14-year-old boy who claimed to know his way through the harbor.

A snowstorm was churning the harbor's waters, and the boat was soon overturned. The two soldiers clung to their overturned boat, but the boy was lost in the icy water. Ida's mother saw their predicament and called to Ida, who was suffering from a cold.

Ida ran to her boat without taking the time to put on a coat or shoes. With the help of her younger brother, Ida was able to haul the two men into her boat and bring them to the lighthouse. One of the men later gave a gold watch to Ida, and for her heroism she became the first woman to receive a gold Congressional medal for lifesaving. The soldiers at Fort Adams showed their appreciation by collecting $218 for Ida.

Years later, Ida recalled this rescue.

I don't know if I was ever afraid. I just went, and that was all there was to it. Now my mother, she wasn't like me. That night when the two soldiers were tipped out of their boat, I was sitting there with my feet in the oven. I had a bad cold. But when I heard those men calling, I started right out, just as I was, with a towel over my shoulders, and mother begged me not to go. She was so nervous that she nearly fainted away while I was out there. But then, she was sickly quite a time. It was my father who showed me how to take people into my boat. You have to draw them over the stern or they will tip you over.

In the Fourth of July parade in 1869, the citizens of Newport presented Ida with a new mahogany boat named Rescue. Ida declined to make a speech. Her reaction as the crowd cheered was simply, "Thank you. Thank you-I don't deserve it."

The boat -- complete with gold-plated oarlocks and red velvet cushions -- was put on wheels for the parade, and Ida rode it past throngs of admirers lining the streets of the city.

At the age of 27, Ida's celebrity status was approaching its peak. She was praised on the pages of Harper's Weekly, Leslie's, the New York Tribune, and many other popular periodicals of the day.

At least two pieces of music were named for her - the Ida Lewis Waltz and the Rescue Polka Mazurka. Ida Lewis hats and scarves flew off store shelves.

It was estimated that 10,000 people visited Lime Rock in 1869. "Of these," reported the Boston Journal, "there were probably not twenty who compensated her for the trouble they gave. . . . People would land at the rock, prowl over the house, quiz the family, pry into the household affairs, patronizingly ask the age of each person and what they lived on, and how they felt when Ida was saving souls."

Ida and her parents were paid a visit by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869. According to some sources, the president's boat landed on the shore, and he got his feet wet when he stepped out. "I have come to see Ida Lewis," Grant happily explained," "and to see her I'd get wet up to my armpits if necessary."

During the same year, Vice President Schuyler Colfax also visited Lime Rock. Admiral Dewey and General Sherman were among the others who made the pilgrimage to Lime Rock in this period, and suffragist Susan B. Anthony twice praised Ida Lewis in her journal.

It was estimated that 10,000 people visited Lime Rock in 1869. "Of these," reported the Boston Journal, "there were probably not twenty who compensated her for the trouble they gave. . . . People would land at the rock, prowl over the house, quiz the family, pry into the household affairs, patronizingly ask the age of each person and what they lived on, and how they felt when Ida was saving souls."

Ida and her parents were paid a visit by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869. According to some sources, the president's boat landed on the shore, and he got his feet wet when he stepped out. "I have come to see Ida Lewis," Grant happily explained," "and to see her I'd get wet up to my armpits if necessary."

During the same year, Vice President Schuyler Colfax also visited Lime Rock. Admiral Dewey and General Sherman were among the others who made the pilgrimage to Lime Rock in this period, and suffragist Susan B. Anthony twice praised Ida Lewis in her journal.

After an engagement of about four years, Ida was quietly married in 1870 to William H. Wilson of Fairfield, Connecticut.

Ida went with her husband to Black Rock Harbor. Little is known of Ida's brief married life, except that she was desperately unhappy and soon returned to Lime Rock. Ida rejected divorce on religious grounds, but she and Wilson were permanently separated.

Ida's father, Hosea Lewis, died in 1872, and his widow became keeper, at least on paper. Ida, of course, had already been the primary keeper of the station for many years.

By 1877, the health of Ida's mother was failing, leaving her with increased housekeeping and care giving responsibilities. Her mother would remain ill and eventually died of cancer in 1887.

In November 1877, Ida saved the lives of three soldiers whose catboat had run into rocks to the west of the lighthouse. This rescue was particularly stressful for Ida, and it resulted in an illness -- probably diphtheria -- that lasted for months.

Ida's father, Hosea Lewis, died in 1872, and his widow became keeper, at least on paper. Ida, of course, had already been the primary keeper of the station for many years.

By 1877, the health of Ida's mother was failing, leaving her with increased housekeeping and care giving responsibilities. Her mother would remain ill and eventually died of cancer in 1887.

In November 1877, Ida saved the lives of three soldiers whose catboat had run into rocks to the west of the lighthouse. This rescue was particularly stressful for Ida, and it resulted in an illness -- probably diphtheria -- that lasted for months.

Ida finally received the official appointment as keeper in 1879, largely through the efforts of an admirer, General Ambrose Everett Burnside, the Civil War hero who became a Rhode Island governor and United States senator.

Left: A fanciful depiction of Ida Lewis from Ripley's Believe it or Not! Courtesy of Cheryl Easterbrooks.

With a salary of $750 per year, Ida was for a time the highest-paid lighthouse keeper in the nation. The extra pay was given "in consideration of the remarkable services of Mrs. Wilson in the saving of lives."

In 1906, a friend was coming for a visit in a small boat when she fell overboard, and Ida rowed out and pulled her friend into her dory. Also in 1906, Ida became the recipient of a pension of $30 monthly from the Carnegie Hero Fund, and the American Cross of Honor Society awarded her a gold medal. The 1906 episode is often referred to as Ida's last rescue, but a newspaper story from August 5, 1909, tells us that Ida saved the lives of five young women whose rowboat was overturned by the steamer Commonwealth.

With a salary of $750 per year, Ida was for a time the highest-paid lighthouse keeper in the nation. The extra pay was given "in consideration of the remarkable services of Mrs. Wilson in the saving of lives."

In 1906, a friend was coming for a visit in a small boat when she fell overboard, and Ida rowed out and pulled her friend into her dory. Also in 1906, Ida became the recipient of a pension of $30 monthly from the Carnegie Hero Fund, and the American Cross of Honor Society awarded her a gold medal. The 1906 episode is often referred to as Ida's last rescue, but a newspaper story from August 5, 1909, tells us that Ida saved the lives of five young women whose rowboat was overturned by the steamer Commonwealth.

Ida wrote in 1907:

Sometimes the spray dashes against these windows so thick I can't see out, and for days at a time the waves are so high that no boat would dare come near the rock, not even if we were starving.

But I am happy. There's a peace on this rock that you don't get on shore. There are hundreds of boats going in and out of this harbor in summer, and it's part of my happiness to know that they are depending on me to guide them safely.

But I am happy. There's a peace on this rock that you don't get on shore. There are hundreds of boats going in and out of this harbor in summer, and it's part of my happiness to know that they are depending on me to guide them safely.

Early one morning in October 1911, Ida Lewis extinguished the light at Lime Rock for the final time.

She became ill that morning and remained in bed for several days. Some say her apparent stroke resulted from worry over a false report that Lime Rock Light was about to be discontinued. Artillery practice at nearby Fort Adams was suspended out of respect for the keeper. Ida Lewis died on October 25, 1911, at the age of 69.

The bells of all the vessels in Newport Harbor tolled for Ida Lewis that night, and flags were at half staff throughout Newport. More than 1,400 people viewed her body at the Thames Street Methodist Church. Among the crowd that gathered to pay its respects were keepers Charles Schoeneman of Newport Harbor Light, Charles Curtis of Rose Island Light, O. F. Kirby of Gull Rocks Light, and Edward Fogerty of the Brenton Reef lightship. The captain and crew of a local lifesaving station in Newport were also present.

The bells of all the vessels in Newport Harbor tolled for Ida Lewis that night, and flags were at half staff throughout Newport. More than 1,400 people viewed her body at the Thames Street Methodist Church. Among the crowd that gathered to pay its respects were keepers Charles Schoeneman of Newport Harbor Light, Charles Curtis of Rose Island Light, O. F. Kirby of Gull Rocks Light, and Edward Fogerty of the Brenton Reef lightship. The captain and crew of a local lifesaving station in Newport were also present.

The buildings at Lime Rock were sold in 1928 for $7,200 and soon became the Ida Lewis Yacht Club.

A new walkway was built to the property, and the old dwelling became the clubhouse. The Ida Lewis Yacht Club can be seen from many of the sightseeing boats out of Newport.

The original lens, manufactured by L. Sautter of Paris, is now on prominent display, along with other artifacts and photos of Ida. A small lamp is still lighted seasonally on the side of the building, serving more as a memorial than as an aid to navigation.

The original lens, manufactured by L. Sautter of Paris, is now on prominent display, along with other artifacts and photos of Ida. A small lamp is still lighted seasonally on the side of the building, serving more as a memorial than as an aid to navigation.

In 1995, the first of the new Coast Guard "keeper class" 175-foot buoy tenders was named the Ida Lewis.

An actress portraying Ida was brought by horse-drawn carriage to the launching ceremony at the Marinette Marine Corporation in Wisconsin. The vessel's homeport is Newport. Click here for photos of the USCGC Ida Lewis.

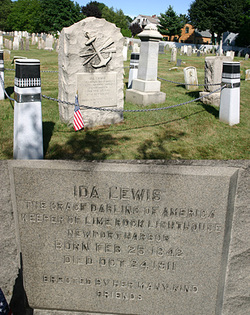

In 2001, crewmembers from the vessel spent time sprucing up Ida's gravesite. Ida Lewis's gravestone is inscribed, "The Grace Darling of America, Keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse, Newport Harbor. Erected by her many friends."

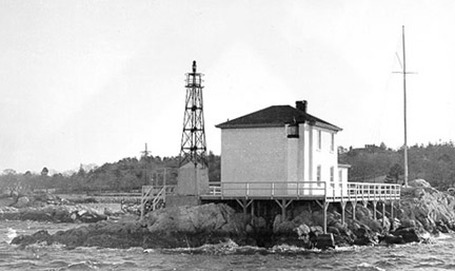

Left: Lime Rock during the period when an automated light on a skeleton tower served as the active aid to navigation. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

In 2001, crewmembers from the vessel spent time sprucing up Ida's gravesite. Ida Lewis's gravestone is inscribed, "The Grace Darling of America, Keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse, Newport Harbor. Erected by her many friends."

Left: Lime Rock during the period when an automated light on a skeleton tower served as the active aid to navigation. U.S. Coast Guard photo.

Keepers: Hosea Lewis (1854-1872); Zoradia Walley Lewis (1872-1879); Idawalley Zoradia (Ida) Lewis (1879-1911); Edward (Evard) Jansen (1911-1927).