History of Egg Rock Light, Winter Harbor, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

Egg Rock, a tiny island in Frenchman Bay, was first mentioned by that name in the American Neptune before the American Revolution. The rocky outpost, which was also known for a time as Gull Island, was named for the proliferation of seabirds’ nests and eggs found there.

Circa late 1800s (National Archives).

Because of the growing seasonal ferry traffic to Bar Harbor, Congress appropriated $15,000 for a light station on Egg Rock in June 1874. There was some delay in procuring title to the island, and the station was constructed during the following year. The 1875 annual report of the Lighthouse Board mentioned the difficulty in landing materials at the exposed location.

The lighthouse went into service on November 1, 1875. It consisted of a short, square brick tower on the center of a one-story wooden keeper’s dwelling. The lantern originally held a fifth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed red light.

The first keeper, Ambrose H. Wasgatt, a Bar Harbor native who was wounded twice in the Civil War, remained at the station for a decade. He experienced a major storm less than five months after the light went into service.

On March 25, 1876, a great gale flooded the dwelling and smashed its windows, moved the fog bell tower 30 feet, and swept away a fuel shed. Wasgatt noted in the station’s log that day that the island was “swept of anything movable.” It was nearly a week before supplies arrived at the station from Bar Harbor. Less than a year later, on January 11, 1877, Wasgatt wrote in the log that another storm “washed down” the bell tower and sent the seas “striking heavy” against the dwelling.

The lighthouse went into service on November 1, 1875. It consisted of a short, square brick tower on the center of a one-story wooden keeper’s dwelling. The lantern originally held a fifth-order Fresnel lens showing a fixed red light.

The first keeper, Ambrose H. Wasgatt, a Bar Harbor native who was wounded twice in the Civil War, remained at the station for a decade. He experienced a major storm less than five months after the light went into service.

On March 25, 1876, a great gale flooded the dwelling and smashed its windows, moved the fog bell tower 30 feet, and swept away a fuel shed. Wasgatt noted in the station’s log that day that the island was “swept of anything movable.” It was nearly a week before supplies arrived at the station from Bar Harbor. Less than a year later, on January 11, 1877, Wasgatt wrote in the log that another storm “washed down” the bell tower and sent the seas “striking heavy” against the dwelling.

After similar damage in a December 1887 storm, a new skeletal bell tower was securely bolted to the rock. Keeper Amaziah R. Small described the 1887 gale: “Sea breaking all over the Rock, breaking the side of Bell Tower. . . . Out house and hen house and in fact everything moveable was washed away.”

U.S. Coast Guard photo

In spite of the lighthouse, wrecks continued in the vicinity of Egg Rock. In October 1894, while Lewis F. Sawyer was keeper, the fishing schooner Amy Hamsen of Boston struck a ledge about a half mile southwest of the lighthouse. Before the schooner sank, its 18 crewmen escaped and rowed safely ashore at Bar Harbor.

On Christmas Eve in 1899, the fishing pinky Julia Ann ran aground and broke apart on the rocky shore of Egg Rock. The two men on board drowned. It was suspected that they were sleeping when the accident occurred. Lewis Sawyer’s son, Heber Sawyer, was keeper at the time. He found much wreckage from the Julia Ann and noted in the log that the crewmen were “undoubtedly drunk.”

Heber Sawyer, who remained at Egg Rock until 1912, experienced two more tremendous storms in early 1900.

On Christmas Eve in 1899, the fishing pinky Julia Ann ran aground and broke apart on the rocky shore of Egg Rock. The two men on board drowned. It was suspected that they were sleeping when the accident occurred. Lewis Sawyer’s son, Heber Sawyer, was keeper at the time. He found much wreckage from the Julia Ann and noted in the log that the crewmen were “undoubtedly drunk.”

Heber Sawyer, who remained at Egg Rock until 1912, experienced two more tremendous storms in early 1900.

Sawyer described the storm of March 2, 1900, as the worst storm in the area in 24 years: “Gale of wind, S. S. E., heavy sea breaking completely over rock, boat house washed away, government boat and boat belonging to man hired by the keeper, completely ruined; keeper’s boat badly smashed. Heavy storm shutters on seaward side of dwelling closed, sea coming around dwelling but doing no damage.”

The boathouse was soon rebuilt. The dwelling was altered around 1900, when a second story was added and the original roof was replaced by the present roof with dormers. In October 1901, the light was upgraded with the installation of a new fourth-order lens. The characteristic was changed from fixed red to flashing red every five seconds. The fog bell striking machinery was repaired the same year.

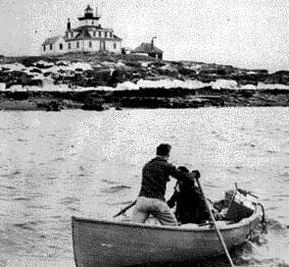

Left: This U.S. Coast Guard photo was published in 1946 with this caption: "Back to duty. After his monthly leave ashore, Linwood Gammon, Coast Guard machinist's mate, returns with provisions to his job as keeper of Egg Rock Lighthouse, Maine."

A new compressed-air fog horn was established in 1904, partly in response to the grounding of the battleship Massachusetts the previous year. Joseph Pulitzer, who had an estate nearby, protested the new fog signal until it was turned to face away from his property. Fog was frequently a problem at Egg Rock. One steamer captain told the Mount Desert Herald in 1881 how he managed to navigate through a particularly thick fog. His explanation was, "I couldn't see anything to run into."

Left: This U.S. Coast Guard photo was published in 1946 with this caption: "Back to duty. After his monthly leave ashore, Linwood Gammon, Coast Guard machinist's mate, returns with provisions to his job as keeper of Egg Rock Lighthouse, Maine."

A new compressed-air fog horn was established in 1904, partly in response to the grounding of the battleship Massachusetts the previous year. Joseph Pulitzer, who had an estate nearby, protested the new fog signal until it was turned to face away from his property. Fog was frequently a problem at Egg Rock. One steamer captain told the Mount Desert Herald in 1881 how he managed to navigate through a particularly thick fog. His explanation was, "I couldn't see anything to run into."

These cannons were once on Egg Rock as part of a coastal defense battery. They are now located near the start of Bar Harbor's Shore Walk, close to the Bar Harbor Inn.

The foghorn was operated for 348 hours in the month of July 1906 alone. It was in operation for 1,813 hours in 1907, the equivalent of 75 full days. The first-class reed horn was replaced in 1938 by an air-diaphragm horn.

“Buster” Dalzell (Maine Lighthouse Museum)

Another fierce storm on February 1, 1908, broke through the shutters and flooded the house. Rocks weighing up to 30 tons were moved by the gale. Heber Sawyer entered a familiar phrase in the station’s log: “Everything moveable was washed away.”

Frank B. Ingalls, the assistant keeper from 1909 to 1912, told the writer Robert Thayer Sterling that landing supplies at Egg Rock was frequently an adventure. While at Egg Rock, he said, he experienced more dunkings going on and off the station than he did at any time during his long career.

On October 30, 1929, Augustus B. Hamor, who had been at Egg Rock since 1913, and his assistant, J. B. Pinkham, saved those on board the stranded schooner Lillian Louise. The men received official commendation from the Department of Commerce.

Keepers at Egg Rock generally rowed to Bar Harbor, four miles away, for supplies. The trip could be treacherous in times of bad weather and rough seas. In March 1918, a keeper was rescued after being trapped in ice while rowing to Bar Harbor.

Clinton L. “Buster” Dalzell, a native of Vinalhaven, Maine, and a U. S. Army veteran who had previously been stationed at Heron Neck, Matinicus Rock, Seguin Island, and Boon Island, arrived at Egg Rock as an assistant keeper in 1933. Dalzell had wed Elizabeth Smith of Vinalhaven at the Heron Neck Light Station in 1930. One February day in 1935, the 28-year-old Dalzell left Egg Rock for the mainland to pick up some batteries for the motor of a boat he had just built.

Frank B. Ingalls, the assistant keeper from 1909 to 1912, told the writer Robert Thayer Sterling that landing supplies at Egg Rock was frequently an adventure. While at Egg Rock, he said, he experienced more dunkings going on and off the station than he did at any time during his long career.

On October 30, 1929, Augustus B. Hamor, who had been at Egg Rock since 1913, and his assistant, J. B. Pinkham, saved those on board the stranded schooner Lillian Louise. The men received official commendation from the Department of Commerce.

Keepers at Egg Rock generally rowed to Bar Harbor, four miles away, for supplies. The trip could be treacherous in times of bad weather and rough seas. In March 1918, a keeper was rescued after being trapped in ice while rowing to Bar Harbor.

Clinton L. “Buster” Dalzell, a native of Vinalhaven, Maine, and a U. S. Army veteran who had previously been stationed at Heron Neck, Matinicus Rock, Seguin Island, and Boon Island, arrived at Egg Rock as an assistant keeper in 1933. Dalzell had wed Elizabeth Smith of Vinalhaven at the Heron Neck Light Station in 1930. One February day in 1935, the 28-year-old Dalzell left Egg Rock for the mainland to pick up some batteries for the motor of a boat he had just built.

Some time later, when the principal keeper, J. B. Pinkham, telephoned the home that was Dalzell’s destination, he learned that Dalzell had never arrived. The police and the Coast Guard were alerted and a search ensued. Pinkham headed out in his own boat, and he found Dalzell’s overturned boat more than a mile from the lighthouse.

Egg Rock Light during its years without a lantern (U.S. Coast Guard)

The search continued for a few days, but it wasn’t until several weeks later that a fishing trawler recovered Dalzell’s body. His third child was born three weeks after his death.

The Coast Guard keepers were removed and the light was automated in 1976. The Coast Guard removed the lantern and installed rotating aerobeacons. This gave the lighthouse a decidedly homely appearance; it was sometimes called the least attractive lighthouse in Maine.

After public complaints, the Coast Guard installed a new aluminum lantern and a 190mm optic in 1986. There is now a VRB-25 optic in place.

Today a boathouse, oil house, and generator house still stand along with the lighthouse. Egg Rock Light is passed by many tour boats and whale watches leaving Bar Harbor. It can also be seen distantly from high points on Mount Desert Island.

The light remains an active aid to navigation. Under the Maine Lights Program administered by the Island Institute of Rockland the lighthouse was officially turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998. It is managed as part of the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

In the fall of 2009, a group of volunteers performed some renovation of the lighthouse. The crews were transported by Bar Harbor Whale Watch, which donated its services. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provided materials for the work, which included staining and repairs. The generator building was re-roofed. Anyone interested in being involved with the maintenance of the lighthouse should contact Zack Klyver of Bar Harbor Whale Watch at 207-288-2386.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Ambrose H. Wasgatt (1875-1885); Amaziah R. Small (1885-1889); Lewis F. Sawyer (1889-1899); Heber G. Sawyer (assistant 1898-1899, principal keeper 1899-1912); Clifford M. Robbins (assistant, 1902); Stephen F. Flood (assistant c. 1902-1905); John E. Purington (assistant, 1905-1909); Frank B. Ingalls (assistant, 1909-?); Harry Smith (assistant, c. 1912); William H. C. Dodge (1912-1916); Winfield Kent (1916-?); Augustus B. Hamor (assistant, then principal keeper, 1913-c.1930); Jules Benjamin Pinkham (c. late 1920s-1940s); Truman Lathrop (c. 1930s); Clinton (Buster) Dalzell (assistant c. 1935, drowned on duty); Ernest H. Mathie (assistant, c. 1940); Linwood Gammon (Coast Guard, c. 1946); T. L. Keene (Coast Guard, c. 1947); Daniel Buckley (c. 1950); ? Wilson (c. 1950); Robert Camp (c. 1950); Arthur L. Wollschlager (Coast Guard, 1954-1957); James Hobart (Coast Guard, 1958-1959); Neil E. Olson (Coast Guard, c. 1960); Harry (Mike) Damm (Coast Guard, 1961); Roger C. Peterson (Coast Guard, 1962); Thomas Collins (Coast Guard, c. 1967); Donald Predmore (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Paul Ranc (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Vince Wixted (Coast Guard, 1974-1976)

The Coast Guard keepers were removed and the light was automated in 1976. The Coast Guard removed the lantern and installed rotating aerobeacons. This gave the lighthouse a decidedly homely appearance; it was sometimes called the least attractive lighthouse in Maine.

After public complaints, the Coast Guard installed a new aluminum lantern and a 190mm optic in 1986. There is now a VRB-25 optic in place.

Today a boathouse, oil house, and generator house still stand along with the lighthouse. Egg Rock Light is passed by many tour boats and whale watches leaving Bar Harbor. It can also be seen distantly from high points on Mount Desert Island.

The light remains an active aid to navigation. Under the Maine Lights Program administered by the Island Institute of Rockland the lighthouse was officially turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998. It is managed as part of the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

In the fall of 2009, a group of volunteers performed some renovation of the lighthouse. The crews were transported by Bar Harbor Whale Watch, which donated its services. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provided materials for the work, which included staining and repairs. The generator building was re-roofed. Anyone interested in being involved with the maintenance of the lighthouse should contact Zack Klyver of Bar Harbor Whale Watch at 207-288-2386.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Ambrose H. Wasgatt (1875-1885); Amaziah R. Small (1885-1889); Lewis F. Sawyer (1889-1899); Heber G. Sawyer (assistant 1898-1899, principal keeper 1899-1912); Clifford M. Robbins (assistant, 1902); Stephen F. Flood (assistant c. 1902-1905); John E. Purington (assistant, 1905-1909); Frank B. Ingalls (assistant, 1909-?); Harry Smith (assistant, c. 1912); William H. C. Dodge (1912-1916); Winfield Kent (1916-?); Augustus B. Hamor (assistant, then principal keeper, 1913-c.1930); Jules Benjamin Pinkham (c. late 1920s-1940s); Truman Lathrop (c. 1930s); Clinton (Buster) Dalzell (assistant c. 1935, drowned on duty); Ernest H. Mathie (assistant, c. 1940); Linwood Gammon (Coast Guard, c. 1946); T. L. Keene (Coast Guard, c. 1947); Daniel Buckley (c. 1950); ? Wilson (c. 1950); Robert Camp (c. 1950); Arthur L. Wollschlager (Coast Guard, 1954-1957); James Hobart (Coast Guard, 1958-1959); Neil E. Olson (Coast Guard, c. 1960); Harry (Mike) Damm (Coast Guard, 1961); Roger C. Peterson (Coast Guard, 1962); Thomas Collins (Coast Guard, c. 1967); Donald Predmore (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Paul Ranc (Coast Guard, c. 1970); Vince Wixted (Coast Guard, 1974-1976)