History of Libby Island Light, Maine

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any images or text from this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

Libby Island is at the entrance to Machias Bay, scene of the American Revolution's first naval battle.

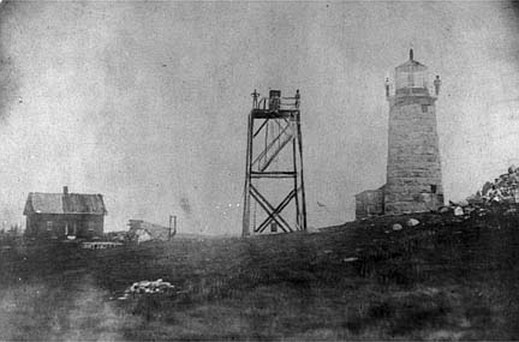

Circa 1859 (National Archives)

Libby is actually two islands connected by a sandbar, with a total area of 120 acres. The island had been farmed since about 1760.

A wooden lighthouse may have been erected as early as 1817, but a new tower was built at the south end of Libby Island by the federal government in 1822, along with a wood-frame keeper's house.

The first rubblestone tower fell down a few months after it was built due to shoddy construction; it was quickly rebuilt.

In 1842, Keeper Isaac Stearns, formerly at Owls Head Light, offered a harsh picture of the light station for I. W. P. Lewis's important report to Congress on the Lighthouse Establishment:

A wooden lighthouse may have been erected as early as 1817, but a new tower was built at the south end of Libby Island by the federal government in 1822, along with a wood-frame keeper's house.

The first rubblestone tower fell down a few months after it was built due to shoddy construction; it was quickly rebuilt.

In 1842, Keeper Isaac Stearns, formerly at Owls Head Light, offered a harsh picture of the light station for I. W. P. Lewis's important report to Congress on the Lighthouse Establishment:

On my taking possession of this place, I found the establishment in a ruinous condition. The lantern of the light-house was very dirty; I scraped off its floor three buckets of broken glass, clay, &c . . . There were, and still are, fifty panes of glass broken in the lantern . . . The lantern shakes very much in a gale of wind . . .

The roof of the tower is a pavement of soapstone, which leaks at every joint. The tower was built in the autumn of 1823, and in April following tumbled down. The present tower was immediately after erected. The mortar used in its erection was so bad, that the tower has nearly fallen down a second time . . . The dwelling-house I occupy is built of brick . . . It is entirely out of repair and in a very uncomfortable state . . .

U.S. Coast Guard photo showing the lighthouse and fog signal building

The tower's original lamps were replaced by a fourth-order Fresnel lens in 1855. A new lantern and deck were installed in 1876.

Libby Island is among the foggiest locations on the Maine coast. A fog bell gave way to a Daboll fog trumpet housed in a building erected in 1884. Before the addition of the fog bell, Libby Island had a single keeper.

The bell required an assistant keeper, so the Lighthouse Board eventually built two new houses for the keepers and their families. In 1918, the fog signal was sounded for a total of 1,906 hours, the most of any Maine station.

Despite the lighthouse and fog signal, the treacherous waters continued to claim vessels. In December 1878, the schooner Caledonia ran into the ledges near Libby Island. The captain, a deckhand, and the steward were killed.

Libby Island is among the foggiest locations on the Maine coast. A fog bell gave way to a Daboll fog trumpet housed in a building erected in 1884. Before the addition of the fog bell, Libby Island had a single keeper.

The bell required an assistant keeper, so the Lighthouse Board eventually built two new houses for the keepers and their families. In 1918, the fog signal was sounded for a total of 1,906 hours, the most of any Maine station.

Despite the lighthouse and fog signal, the treacherous waters continued to claim vessels. In December 1878, the schooner Caledonia ran into the ledges near Libby Island. The captain, a deckhand, and the steward were killed.

Only two passengers on the vessel survived to be rescued from the rigging by a volunteer lifesaving crew.

In a September 1892 storm, Captain John Brown of the Nova Scotia vessel Princeport tried to take shelter in Machias Bay and ran into the bar connecting the two Libby Islands.

The ship immediately began to break apart as the crew huddled on the bow. The keepers from Libby Island arrived and rescued the men, who probably would have been dead minutes later.

Henry M. Cuskley became keeper in 1903. He later described the 1906 wreck in dense fog of the three-masted schooner Ella G. Ells to historian Edward Rowe Snow. All hands on the schooner were lost except the captain, who drifted ashore on the roof of the ship's cabin. The vessel had been headed from New York City to St. John, New Brunswick.

The ship immediately began to break apart as the crew huddled on the bow. The keepers from Libby Island arrived and rescued the men, who probably would have been dead minutes later.

Henry M. Cuskley became keeper in 1903. He later described the 1906 wreck in dense fog of the three-masted schooner Ella G. Ells to historian Edward Rowe Snow. All hands on the schooner were lost except the captain, who drifted ashore on the roof of the ship's cabin. The vessel had been headed from New York City to St. John, New Brunswick.

Hervey Wass became keeper at Libby Island in 1919. His son Philmore Wass wrote a book about his years on the island called Lighthouse in My Life.

Henry Cuskley (courtesy of Chuck Petlick)

This delightful book provides a detailed record of life on an offshore lighthouse station. During this period there were as many as 20 people living at Libby among the families of the keeper and two assistants.

Many different games, including baseball, were played on the island. One of Phil Wass's favorite games was called "Grass is Poison." In this game the children had to walk around the perimeter of the island without touching any grass. This necessitated a climb down a 50-foot cliff near the lighthouse, without the knowledge of the parents, of course.

Phil Wass's sister, Hazel, was taught to play piano by the keeper's wife at their previous station, Whitehead Light, and Keeper Wass bought a piano for Libby Island. Music could often be heard drifting from the island. Hazel Wass once gathered the children on Libby Island and put on a musical revue.

In his book, Phil Wass described his feelings of awe regarding the lighthouse inspector, Royal Luther. Young Phil sometimes confused the concepts of God and Luther in his young mind; they were both all-powerful figures to the lighthouse families. Inspector Luther would arrive unannounced on the Lighthouse Tender Hibiscus, and the children would tag along as he met with Keeper Wass and toured the station. The buildings were always in perfect order, with the entire family pitching in to make the place sparkle. Young Phil's job was to polish the brass in the keeper's house.

Many different games, including baseball, were played on the island. One of Phil Wass's favorite games was called "Grass is Poison." In this game the children had to walk around the perimeter of the island without touching any grass. This necessitated a climb down a 50-foot cliff near the lighthouse, without the knowledge of the parents, of course.

Phil Wass's sister, Hazel, was taught to play piano by the keeper's wife at their previous station, Whitehead Light, and Keeper Wass bought a piano for Libby Island. Music could often be heard drifting from the island. Hazel Wass once gathered the children on Libby Island and put on a musical revue.

In his book, Phil Wass described his feelings of awe regarding the lighthouse inspector, Royal Luther. Young Phil sometimes confused the concepts of God and Luther in his young mind; they were both all-powerful figures to the lighthouse families. Inspector Luther would arrive unannounced on the Lighthouse Tender Hibiscus, and the children would tag along as he met with Keeper Wass and toured the station. The buildings were always in perfect order, with the entire family pitching in to make the place sparkle. Young Phil's job was to polish the brass in the keeper's house.

At the age of 14, Phil Wass was assigned the duty of collecting information for Robert Thayer Sterling, who was writing his book, Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them.

Phil explored the attic and discovered a box of old records, including accounts of many shipwrecks. Later all these records went to the Lighthouse Service office in Portland.

The families at Libby Island supplemented their diet by catching fish and lobster. Cranberries grew in abundance on the island; blueberries and raspberries were available on nearby islands. The keepers also kept a cow and chickens for milk and eggs.

Right: Jasper L. Cheney, an assistant keeper and later head keeper, lived on Libby Island with his family from 1933 to 1949. He is seen here with his wife Tryphena, son Roland and daughter Ella in the 1930s. Courtesy of Ella Cheney Robinson and Jeff Robinson.

In 1933, Jasper L. Cheney arrived as an assistant keeper under Hervey Wass. His daughter Ella remembered in a 2003 interview that a swimming hole was created by the men, who dynamited some ledges so that each incoming tide filled the hole with salt water. "The sun would warm the cold seawater so we could swim in it. It was a place where young and old all spent lots of hours cooling off and getting tanned."

The families at Libby Island supplemented their diet by catching fish and lobster. Cranberries grew in abundance on the island; blueberries and raspberries were available on nearby islands. The keepers also kept a cow and chickens for milk and eggs.

Right: Jasper L. Cheney, an assistant keeper and later head keeper, lived on Libby Island with his family from 1933 to 1949. He is seen here with his wife Tryphena, son Roland and daughter Ella in the 1930s. Courtesy of Ella Cheney Robinson and Jeff Robinson.

In 1933, Jasper L. Cheney arrived as an assistant keeper under Hervey Wass. His daughter Ella remembered in a 2003 interview that a swimming hole was created by the men, who dynamited some ledges so that each incoming tide filled the hole with salt water. "The sun would warm the cold seawater so we could swim in it. It was a place where young and old all spent lots of hours cooling off and getting tanned."

"The men worked very hard on the island," recalled Ella. "Every building was kept in A-1 shape always. Painting was an endless job both inside and out. The foghorn and light were gone over every day to make sure they were in perfect order. It's odd, but when the foghorn was running at night and stopped because it ran out of fuel, all three keepers would awaken and be there in a matter of minutes."

December 1929 (National Archives).

A 1939 article by Richard Hallett in Technology Review described a visit of the lighthouse tender Ilex to Libby Island soon after a winter storm:

Libby Island showed the mark of the storm. The wooden breakwater was stove in. The boathouse, high up on this high-shouldered island, was half a ruin. . . . Even now seas dropped aboard the west end of the island with a noise like a cartload of lumber being upset; and when we neared the slips, we saw that one of them . . . had been booted clean away.

Libby Island's . . . high crags were hung with massive icicles, and the wagon tracks leading to the light were lumpy with brine ice. Even the trees were sheathed in ice to the last twig and looked half winterkilled. Lobster traps were blown all over the place.

George Staples was still in his teens when he was assigned to Libby Island by the Coast Guard in 1955. The station had become a males-only "stag station" by this time. There were always at least two, sometimes three, Coast Guardsmen on the island at one time. "You got to the point where you didn't talk to the other guy," Staples recalled in a 2013 interview. "There was nothing left to talk about." Although Staples has some nostalgia for his lighthouse keeping days, he sums it up by saying, "I can't say it was fun, because it wasn't."

In 1974, the Fresnel lens was removed and the lighthouse was automated. Most of the buildings except the lighthouse tower and fog signal building have been destroyed over the years.

Libby Island showed the mark of the storm. The wooden breakwater was stove in. The boathouse, high up on this high-shouldered island, was half a ruin. . . . Even now seas dropped aboard the west end of the island with a noise like a cartload of lumber being upset; and when we neared the slips, we saw that one of them . . . had been booted clean away.

Libby Island's . . . high crags were hung with massive icicles, and the wagon tracks leading to the light were lumpy with brine ice. Even the trees were sheathed in ice to the last twig and looked half winterkilled. Lobster traps were blown all over the place.

George Staples was still in his teens when he was assigned to Libby Island by the Coast Guard in 1955. The station had become a males-only "stag station" by this time. There were always at least two, sometimes three, Coast Guardsmen on the island at one time. "You got to the point where you didn't talk to the other guy," Staples recalled in a 2013 interview. "There was nothing left to talk about." Although Staples has some nostalgia for his lighthouse keeping days, he sums it up by saying, "I can't say it was fun, because it wasn't."

In 1974, the Fresnel lens was removed and the lighthouse was automated. Most of the buildings except the lighthouse tower and fog signal building have been destroyed over the years.

Under the Maine Lights Program, the lighthouse was turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1998.

U.S. Coast Guard photo by Chris Ledwith

The Coast Guard completed an overhaul of the tower in the summer of 2000, including the conversion of the light to solar power. As part of the restoration the tower was returned to its original unpainted look. The lighthouse can be seen distantly from the mainland but is best viewed by private boat.

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John McKellar (1822-?); Isaac Sterns (1842-1846); Matthew Kellar (1846-1850 and 1853-1860); John Grant (1850-1853); James W. Foster (1860-1871); John C. Ames (1871-1877); Charles A. Drisko (1877-1883); William H. Drisko (1883-1885); A. M. Drisko (1885-1891); Danford O. French (1891-1895); Fred W.Morong (1895-1898, also 1910); Bela W. Proctor (first assistant, 1894-?); Roscoe G. Johnson (second assistant 1894-?, head keeper 1898-1903); Almon Mitchell (c. 1899-1902); Henry M. Cuskley (1903-1912); Charles A. Kenney (1905-1912); Albion Faulkingham (c. 1915?); Hervey H. Wass (1919-1940), Justin Foss (first assistant, 1919-1932); George Woodward (second assistant, ?-1923); Everett Mitchell (second assistant, c. 1920s); Bernard Small (second assistant, c. 1920s); James McCloud (second assistant, c. 1930s); John Beal (second assistant, c. 1930s); Gleason W. Colbeth (first assistant, 1932-1945), Jasper L. Cheney (assistant 1933-1940, principal keeper 1940-1949), Millard Urquhart (c. 1938-1940); Gene Watts (Coast Guard, 1949), Bill Bybee (Coast Guard, 1949-1950), Robert W. Brooks (Coast Guard Fireman First Class, c. 1950-1951); Frank Dernoga (Coast Guard, c. 1952-1954); ENC Paul Joseph Kessler (Coast Guard, 1953); George Staples (Coast Guard, 1955 and 1963, officer in charge, 1963); Roger Lee Drinkwater (Coast Guard, c. 1958), BM1 Albert Ross (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1960); Fireman Stephen L. Gray (Coast Guard, 1960); SN George Morrison (Coast Guard, 1963); EN2 Larry Smith (Coast Guard, c. 1963); Harold Allen (Coast Guard, c. 1965-1966), Richard "Gary" Craig (Coast Guard, 1966-1967); Donald Costantino (Coast Guard, 1968-1969), Alan (Skip) Skidmore (Coast Guard, 1969-1972), Jay Novegrod (Coast Guard, c. 1969-1972)

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

John McKellar (1822-?); Isaac Sterns (1842-1846); Matthew Kellar (1846-1850 and 1853-1860); John Grant (1850-1853); James W. Foster (1860-1871); John C. Ames (1871-1877); Charles A. Drisko (1877-1883); William H. Drisko (1883-1885); A. M. Drisko (1885-1891); Danford O. French (1891-1895); Fred W.Morong (1895-1898, also 1910); Bela W. Proctor (first assistant, 1894-?); Roscoe G. Johnson (second assistant 1894-?, head keeper 1898-1903); Almon Mitchell (c. 1899-1902); Henry M. Cuskley (1903-1912); Charles A. Kenney (1905-1912); Albion Faulkingham (c. 1915?); Hervey H. Wass (1919-1940), Justin Foss (first assistant, 1919-1932); George Woodward (second assistant, ?-1923); Everett Mitchell (second assistant, c. 1920s); Bernard Small (second assistant, c. 1920s); James McCloud (second assistant, c. 1930s); John Beal (second assistant, c. 1930s); Gleason W. Colbeth (first assistant, 1932-1945), Jasper L. Cheney (assistant 1933-1940, principal keeper 1940-1949), Millard Urquhart (c. 1938-1940); Gene Watts (Coast Guard, 1949), Bill Bybee (Coast Guard, 1949-1950), Robert W. Brooks (Coast Guard Fireman First Class, c. 1950-1951); Frank Dernoga (Coast Guard, c. 1952-1954); ENC Paul Joseph Kessler (Coast Guard, 1953); George Staples (Coast Guard, 1955 and 1963, officer in charge, 1963); Roger Lee Drinkwater (Coast Guard, c. 1958), BM1 Albert Ross (Coast Guard officer in charge c. 1960); Fireman Stephen L. Gray (Coast Guard, 1960); SN George Morrison (Coast Guard, 1963); EN2 Larry Smith (Coast Guard, c. 1963); Harold Allen (Coast Guard, c. 1965-1966), Richard "Gary" Craig (Coast Guard, 1966-1967); Donald Costantino (Coast Guard, 1968-1969), Alan (Skip) Skidmore (Coast Guard, 1969-1972), Jay Novegrod (Coast Guard, c. 1969-1972)