History of Conimicut Light, Warwick, Rhode Island

© Jeremy D'Entremont. Do not reproduce any part of this website without permission of the author.

More information: Front page / Photos / Bibliography / Cruises / Postcards

The lighthouse established in 1828 at Nayatt Point, on the east side of the entrance to the Providence River, proved insufficient to warn navigators of the dangerous sandbar extending out from Conimicut Point across at the west side.

U.S. Coast Guard

An unlighted wooden daymark was established as a warning in the middle of the river's mouth by 1858. That first daymark was swept away by ice in 1860, and a spar buoy took its place.

A new granite tower was built in 1866, and at the request of local mariners the daymark was converted into a lighted aid to navigation in November 1868. Nayatt Point Light was then discontinued.

There was no dwelling at the new light, meaning the early keepers had to make a dangerous one-mile rowboat trip to tend the light. In 1874, a five-room house was built on the pier at the light.

A new granite tower was built in 1866, and at the request of local mariners the daymark was converted into a lighted aid to navigation in November 1868. Nayatt Point Light was then discontinued.

There was no dwelling at the new light, meaning the early keepers had to make a dangerous one-mile rowboat trip to tend the light. In 1874, a five-room house was built on the pier at the light.

On February 27, 1874, Horace W. Arnold was appointed keeper. Arnold, a Rhode Island native and Civil War veteran, had just served two years as an assistant keeper at Beavertail Light.

U.S. Coast Guard

A little over a year later, in early March 1875, Arnold was at the five-room keeper’s dwelling at Conimicut Light with his young son, when drifting ice, driven by strong northeast winds, abruptly smashed into the structure.

The Arnolds were lucky to escape with their lives as the house broke apart. They were rescued several hours later by the tug Reliance, captained by Nat Sutton. Sutton spotted Arnold on a mattress on a drifting ice floe, later describing him as "sitting like a man on a magic carpet." The keeper's hands and feet were frozen and it was some months before he could fully resume his duties.

Captain John Weeden, keeper at the Sabin Point Lighthouse, volunteered to row to Conimicut Light and care for the light. As he was performing his duties, Weeden's boat was destroyed by ice, stranding him. A snowstorm set in, and Weeden calmly prepared himself a breakfast of tea and jonnycakes. He then rang the fog bell until he was finally rescued that evening. For the next few years the keepers lived at the house at the old Nayatt Point Light and rowed to the light.

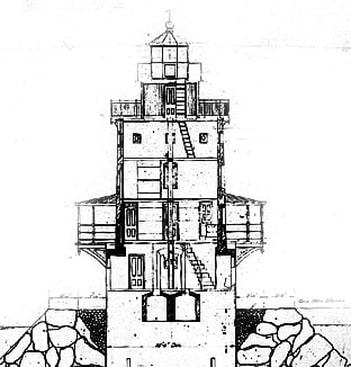

In 1882 the old granite tower was torn down and a new cast-iron sparkplug-style light was built, with a fourth-order Fresnel lens and a fixed white light visible for 15 miles. The caisson is sunk 10 feet into the bottom of the bay and is constructed of cast-iron plates. When the caisson was filled with concrete, space was left for a basement with space for water and fuel storage.

The keeper's bedroom was one level below the lantern room. The room was described in 1891 as pretty, with blue walls, an ash bedroom set and arched windows.

Horace Arnold was credited with saving the lives of five people during his 12 years at Conimicut Light. An article in the Newport Daily News mentioned in passing that one of Arnold’s sons lost his life after a fall from the lighthouse onto the rocks below, but no details were provided and it’s not clear if this report was accurate. Arnold left in 1886 to become keeper of the lighthouse at the northern tip of Conanicut Island, where he would stay for the remaining 28 years of his career.

The early keepers generally remained at the offshore lighthouse for a few years at most, but Daniel MacDonald remained for 11 years, 1895 to 1906.

On March 1, 1905, the keeper’s two small sons—six-year-old Leslie and three-year-old Melton—were playing on the rocks near the base of the tower. Leslie was poking at the passing ice cakes with a pole, when little Melton lost his footing suddenly and plunged into the freezing water.

When he heard his brother’s frantic cries, Leslie took instant action. Easing himself down until he was waist deep in water, Leslie extended the pole far enough for Melton to grasp it. With his older brother exhorting him to hang on, the boy was pulled to safety.

The Arnolds were lucky to escape with their lives as the house broke apart. They were rescued several hours later by the tug Reliance, captained by Nat Sutton. Sutton spotted Arnold on a mattress on a drifting ice floe, later describing him as "sitting like a man on a magic carpet." The keeper's hands and feet were frozen and it was some months before he could fully resume his duties.

Captain John Weeden, keeper at the Sabin Point Lighthouse, volunteered to row to Conimicut Light and care for the light. As he was performing his duties, Weeden's boat was destroyed by ice, stranding him. A snowstorm set in, and Weeden calmly prepared himself a breakfast of tea and jonnycakes. He then rang the fog bell until he was finally rescued that evening. For the next few years the keepers lived at the house at the old Nayatt Point Light and rowed to the light.

In 1882 the old granite tower was torn down and a new cast-iron sparkplug-style light was built, with a fourth-order Fresnel lens and a fixed white light visible for 15 miles. The caisson is sunk 10 feet into the bottom of the bay and is constructed of cast-iron plates. When the caisson was filled with concrete, space was left for a basement with space for water and fuel storage.

The keeper's bedroom was one level below the lantern room. The room was described in 1891 as pretty, with blue walls, an ash bedroom set and arched windows.

Horace Arnold was credited with saving the lives of five people during his 12 years at Conimicut Light. An article in the Newport Daily News mentioned in passing that one of Arnold’s sons lost his life after a fall from the lighthouse onto the rocks below, but no details were provided and it’s not clear if this report was accurate. Arnold left in 1886 to become keeper of the lighthouse at the northern tip of Conanicut Island, where he would stay for the remaining 28 years of his career.

The early keepers generally remained at the offshore lighthouse for a few years at most, but Daniel MacDonald remained for 11 years, 1895 to 1906.

On March 1, 1905, the keeper’s two small sons—six-year-old Leslie and three-year-old Melton—were playing on the rocks near the base of the tower. Leslie was poking at the passing ice cakes with a pole, when little Melton lost his footing suddenly and plunged into the freezing water.

When he heard his brother’s frantic cries, Leslie took instant action. Easing himself down until he was waist deep in water, Leslie extended the pole far enough for Melton to grasp it. With his older brother exhorting him to hang on, the boy was pulled to safety.

About three weeks later, Leslie received a letter from Wilbert E. Longfellow, commander of the Rhode Island department of the United States Volunteer Life Saving Corps. “I fully realize the very natural antipathy which any person has of an icy bath in the winter,” wrote Longfellow, “and the courage it took to make the plunge for the little chap who had fallen in.” A few weeks later, a party from the corps arrived at the lighthouse to present Leslie with a medal of honor for his cool-headed rescue.

The keeper in 1922 was Ellsworth Smith. His 30-year-old wife, Nellie, had lived with him in the lighthouse for about a year, along with their two sons, aged two and five (or six, according to one account). On June 10, Keeper Smith went to Providence to take care of some business.

According to a story the next day in the New York Times, Nellie Smith had grown “morose and despondent” during her year of lighthouse life. She had asked her husband to take her to shore to live, and had threatened suicide. That day, while her husband was gone, Nellie found his keys and opened the medicine cabinet. She gave poison tablets to each of her sons, telling them they were candy. The older boy spit out the tablet, but swallowed enough to become ill.

Ellsworth Smith returned in his dory to the lighthouse around 6:00 p.m. He entered to find his younger son, Russell, lying dead on a table, and his wife dead in bed. The older boy, Ellsworth Jr., was in agony, and Smith rushed him ashore for medical assistance. Meanwhile, authorities were notified that the lighthouse had been abandoned and a warning was issued to shipping interests. After an antidote was administered, the surviving boy was taken to the home of the keeper’s sister to recuperate. It isn’t clear if Ellsworth Smith spent any more time at the lighthouse, but it seems doubtful.

The keeper in 1922 was Ellsworth Smith. His 30-year-old wife, Nellie, had lived with him in the lighthouse for about a year, along with their two sons, aged two and five (or six, according to one account). On June 10, Keeper Smith went to Providence to take care of some business.

According to a story the next day in the New York Times, Nellie Smith had grown “morose and despondent” during her year of lighthouse life. She had asked her husband to take her to shore to live, and had threatened suicide. That day, while her husband was gone, Nellie found his keys and opened the medicine cabinet. She gave poison tablets to each of her sons, telling them they were candy. The older boy spit out the tablet, but swallowed enough to become ill.

Ellsworth Smith returned in his dory to the lighthouse around 6:00 p.m. He entered to find his younger son, Russell, lying dead on a table, and his wife dead in bed. The older boy, Ellsworth Jr., was in agony, and Smith rushed him ashore for medical assistance. Meanwhile, authorities were notified that the lighthouse had been abandoned and a warning was issued to shipping interests. After an antidote was administered, the surviving boy was taken to the home of the keeper’s sister to recuperate. It isn’t clear if Ellsworth Smith spent any more time at the lighthouse, but it seems doubtful.

Control of the nation's lighthouses went to the Coast Guard in 1939, but civilian Lighthouse Service keepers remained in charge at Conimicut until the late 1950s when Coast Guard keepers finally took over.

Photo by Fred Mikkelsen

When 17-year-old Bob Onosko arrived in 1957, the Coast Guard's officer in charge at Conimicut was First Class Boatswain's Mate Bob Reedy, who had taken over when the last civilian keeper, a Mr. Powell, had died at the station. The crew's water supply came from rainwater collected in a basement cistern. The water was piped to the kitchen by the use of a hand pump. "On occasions Bob Reedy would pour a gallon of bleach in the cistern as a precaution," says Onosko. "I still remember how bad the water tasted after that."

18-year-old Fred Mikkelsen was assigned to Conimicut Light in 1958. The officer in charge when Mikkelsen arrived was First Class Boatswain's Mate Joe Bakken. When fog rolled in, the old Gamewell Fog Bell Striker was put to work. The machine "had to be maintained, oiled and cleaned," according to Mikkelsen. It ran about two hours on 10 minutes of winding. The bell would be struck automatically every 10 seconds, but inside the tower the noise of the striking machine was louder than the bell. If the striker stopped, "the silence would wake me from a sound sleep," Mikkelsen recalls.

18-year-old Fred Mikkelsen was assigned to Conimicut Light in 1958. The officer in charge when Mikkelsen arrived was First Class Boatswain's Mate Joe Bakken. When fog rolled in, the old Gamewell Fog Bell Striker was put to work. The machine "had to be maintained, oiled and cleaned," according to Mikkelsen. It ran about two hours on 10 minutes of winding. The bell would be struck automatically every 10 seconds, but inside the tower the noise of the striking machine was louder than the bell. If the striker stopped, "the silence would wake me from a sound sleep," Mikkelsen recalls.

During Bob Onosko's year at the lighthouse, he was frequently alone and there were never more than two men on duty. During Mikkelsen's three years, the official complement of four men was never realized.

Mikkelsen's scariest experience in his three years at the lighthouse was a 1960 hurricane. At the height of the storm, the surging sea blocked all sunlight through the galley windows on the first level. When he went to the lantern to check the light, Mikkelsen became aware that the lighthouse was moving in the storm, with the greatest movement near the top. "It would bang you against the wall," he says, "and you had to hang on to the handrail of the ladder."

Right: The lighthouse galley. Photo by Fred Mikkelsen.

Like so many lighthouses, this one has its tales of ghostly hauntings. In the January/February 2005 issue of Lighthouse Digest magazine, retired Coast Guardsman Paul Baptiste recalled being assigned to relieve the civilian keeper in 1955 for two days. “The first day went by okay and I slept in the storage room, just below the lantern room,” wrote Baptiste.

The next day, the keeper's wife asked him if he had seen a ghost during the night. She explained that the ghost of a former keeper's wife often appeared at night in the doorway of the room where Baptiste had slept. “I didn't sleep there that night and I was far away from Conimicut Lighthouse the next day,” Baptiste recalled.

Fred Mikkelsen says that he never experienced any ghosts, but says. “Others in the crew thought they had seen shadows or perceived movement along the stairway near the second landing.”

One summer morning in 1959 or 1960, Officer in Charge Sam E. Harris and Mikkelsen awoke to find bloody footprints leading from the boat landing right into the kitchen. The two men put no stock in ghost stories. “We figured one of the shellfish ‘pirates,’ who often worked illegally at night, had come in looking for some first aid materials or help and then left,” says Mikkelsen. After that, the crewmen made a point of locking the doors every night.

The light was fully electrified via cable from shore in 1960, shortly after Fred Mikkelsen left. The IOV lamp had been in use for 47 years. Although many sources say this was the last lighthouse in the nation to be converted to electricity, there was at least one that came later-Burnt Island Light in Maine (1962). The light was automated and the resident keepers were removed in 1963.

A 1955 boat landing, made of wood, was badly damaged by ice and was replaced by a new steel landing in 1994. Personnel from Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team Bristol had painted the exterior of the tower in the previous year.

Right: The lighthouse galley. Photo by Fred Mikkelsen.

Like so many lighthouses, this one has its tales of ghostly hauntings. In the January/February 2005 issue of Lighthouse Digest magazine, retired Coast Guardsman Paul Baptiste recalled being assigned to relieve the civilian keeper in 1955 for two days. “The first day went by okay and I slept in the storage room, just below the lantern room,” wrote Baptiste.

The next day, the keeper's wife asked him if he had seen a ghost during the night. She explained that the ghost of a former keeper's wife often appeared at night in the doorway of the room where Baptiste had slept. “I didn't sleep there that night and I was far away from Conimicut Lighthouse the next day,” Baptiste recalled.

Fred Mikkelsen says that he never experienced any ghosts, but says. “Others in the crew thought they had seen shadows or perceived movement along the stairway near the second landing.”

One summer morning in 1959 or 1960, Officer in Charge Sam E. Harris and Mikkelsen awoke to find bloody footprints leading from the boat landing right into the kitchen. The two men put no stock in ghost stories. “We figured one of the shellfish ‘pirates,’ who often worked illegally at night, had come in looking for some first aid materials or help and then left,” says Mikkelsen. After that, the crewmen made a point of locking the doors every night.

The light was fully electrified via cable from shore in 1960, shortly after Fred Mikkelsen left. The IOV lamp had been in use for 47 years. Although many sources say this was the last lighthouse in the nation to be converted to electricity, there was at least one that came later-Burnt Island Light in Maine (1962). The light was automated and the resident keepers were removed in 1963.

A 1955 boat landing, made of wood, was badly damaged by ice and was replaced by a new steel landing in 1994. Personnel from Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team Bristol had painted the exterior of the tower in the previous year.

Some photos by Fred Mikkelsen:

In the spring of 1997 a Coast Guard crew during routine maintenance at the lighthouse found a stranded coyote that apparently had managed to swim to the lighthouse. The Coast Guardsmen got the animal into a cage and it was eventually released in the woods.

On September 29, 2004, a ceremony was held to announce the transfer of the lighthouse to the city of Warwick under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000.

Below: WPRI-TV news story on the lighthouse (August 30, 2016).

Keepers: (This list is a work in progress. If you have any information on the keepers of this lighthouse, I'd love to hear from you. You can email me at [email protected]. Anyone copying this list onto another web site does so at their own risk, as the list is always subject to updates and corrections.)

Davis Perry (1868-1869), H. Perry (assistant, 1869), ? Healy (1869-1871), C. Rounds (?) (assistant, 1869-1870), Charles A. Wells (assistant, 1870), Robert H. Tobin (assistant, 1870-1871), John Walker (1871-1874), James King (assistant, 1871-1872), Benjamin (?) King (assistant, 1872), William Crawford (assistant, 1873), ? Beaumont (assistant, 1874), Horace Arnold (1874-1886), Francis E. Arnold (assistant, 1878-1881), E. M. Buckingham (assistant, 1881), Benedict A. Winslow (assistant, 1881-1882), Ernest L. Arnold (assistant, 1882-1884), Benajah B. Gray (1886-1890), Edward L. Hunt (1890-1892), Joseph B. Eddy (1892-1894), Thomas S. Fishburne (1894-1895), Daniel MacDonald (1895-1906), Joseph Burke (1906), E. R. Curtis (1906-1907), Daniel L. Reardon (1907-1909), Nicolai Jensen (Jansen) (1909-c.1920?), Ellsworth Smith (c. 1921-1922), Joseph Bakken (Coast Guard, c. 1950s); ? Powell (?-c. 1957), Bob Onosko (Coast Guard, 1957), Bob Reedy (Coast Guard, c. 1957), Fred Mikkelsen (Coast Guard 1958-1961) ; Sam E. Harris (Coast Guard, c. 1960); Russell Barnhart (Coast Guard, c. early 1960s); David Burns (Coast Guard, 1961-1962); Bud King (c. early 1960s; lamplighter?)

Davis Perry (1868-1869), H. Perry (assistant, 1869), ? Healy (1869-1871), C. Rounds (?) (assistant, 1869-1870), Charles A. Wells (assistant, 1870), Robert H. Tobin (assistant, 1870-1871), John Walker (1871-1874), James King (assistant, 1871-1872), Benjamin (?) King (assistant, 1872), William Crawford (assistant, 1873), ? Beaumont (assistant, 1874), Horace Arnold (1874-1886), Francis E. Arnold (assistant, 1878-1881), E. M. Buckingham (assistant, 1881), Benedict A. Winslow (assistant, 1881-1882), Ernest L. Arnold (assistant, 1882-1884), Benajah B. Gray (1886-1890), Edward L. Hunt (1890-1892), Joseph B. Eddy (1892-1894), Thomas S. Fishburne (1894-1895), Daniel MacDonald (1895-1906), Joseph Burke (1906), E. R. Curtis (1906-1907), Daniel L. Reardon (1907-1909), Nicolai Jensen (Jansen) (1909-c.1920?), Ellsworth Smith (c. 1921-1922), Joseph Bakken (Coast Guard, c. 1950s); ? Powell (?-c. 1957), Bob Onosko (Coast Guard, 1957), Bob Reedy (Coast Guard, c. 1957), Fred Mikkelsen (Coast Guard 1958-1961) ; Sam E. Harris (Coast Guard, c. 1960); Russell Barnhart (Coast Guard, c. early 1960s); David Burns (Coast Guard, 1961-1962); Bud King (c. early 1960s; lamplighter?)